Outposts of opportunity / Goma

Mine field

Wars and volcanoes have made Goma a dangerous place to call home. But with a fragile peace now in place in the DR Congo, everyone from Lebanese traders to Serbian pilots are arriving in town. The lure: the region’s vast mineral wealth.

When evening comes in Goma, the terrace of the Cap Kivu Hotel is definitely one of the places to see – but try not to be seen. As he finishes his beer, a rebel warlord wanted in the Hague for crimes against humanity grudgingly settles his €100 bill. Later, a plump colonel from the Congolese army strolls in. Most nights, groups of UN staff and NGO workers sit drinking away the stress of trying to save the world.

“Welcome to Goma,” says hotel manager Jean-Marie Mungazi with a smile. “We seem to have something for everyone here and now business could really start picking up.”

Once a top tourist destination and a playground for billionaire dictators and the jet set, Goma could be both the most cursed and blessed city on the planet. Nestled on the idyllic shore of Lake Kivu against a spectacular backdrop of rolling hills and rugged volcanoes, it is the gateway to the mineral wealth of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. For the past 15 years, this city of 500,000 inhabitants has also been at the centre of one of the world’s worst war zones.

If the terrace at the Cap Kivu offers a snapshot of the strolling cast of rogues, humanitarians and entrepreneurs that populate Goma, then the hotel’s history encapsulates the perils and possibilities of doing business in the city.

Perhaps 1994 was not the best year for Antoine Lubongera, a local beer magnate, to start building his Cap Kivu Hotel. That was the year that two million Hutu refugees fled over the border from neighbouring Rwanda fearing retribution for their role in that country’s genocide. Over the next few years, Goma became the launch pad for two civil wars that engulfed the Congo in anarchy and looting.

Work only continued on the hotel during the periods of peace. Then, in 2002, just as things seemed to be settling down, nature overtook man as the main threat to Goma. This was when Nyiragongo, one of the most active volcanoes in the world, erupted, covering swathes of the city in lava and ash.

Nowadays a fragile peace appears to be on the horizon for Goma and the final touches can finally be applied to the Cap Kivu. A military operation to root out the remaining Rwandan genocidaires from eastern Congo has Mungazi hoping that the fluctuating business booms caused by occasional influxes of journalists, NGO workers and UN staff will give way to a more steady flow of well-heeled tourists.

“Sometimes war was good for us but if all stays peaceful then by this summer we should see the number of tourists really pick up,” he says. “We have the gorillas in the national park, the volcano and the beauty of Lake Kivu.”

While Nyiragongo’s magma turned most of the town into hell, it also ended up leading to a building boom. Now houses resembling the glitzier end of a Moscow suburb are going up along the lakefront and SUVs cruise along the pot-holed roads alongside wooden carts.

It’s not difficult to see where the money has come from. Linson Pan says that business is not as good as it used to be, but for a 27-year-old he still seems to be doing pretty well. Standing on the steps of his fast-expanding plant, the joint owner of TTT Mining watches his Congolese workers on €3 a day haul sacks of tin ore across the forecourt.

For the past two years, Pan and his business partner Mr Woo, both Chinese, have been buying up metals around the region for processing in their factory in Guangzhou, China. They are very careful, Pan claims, never to buy the ore from mines controlled by rebel armies.

The back of Pan’s business card lists an array of minerals – cobalt, copper, colfram, cassiterite – that hint at the vast wealth of eastern Congo. The region also contains huge reserves of diamonds, gold, timber and most of the world’s coltan, an ore containing elements used in DVD players and mobile phones.

Transporting all of this around the region are people such as Milorad. As he comes down the steps of his Boeing cargo plane, his white mane blowing in the breeze, the Serbian pilot has just one thing on his mind – sex. “You won’t see me around town tonight. I just get to my hotel room and call them in,” he says, winking. “I’ve been told not to pay more than $10 as it will screw up the local market.”

Beyond him, a crew of three Colombian pilots and one Peruvian don’t look quite so at ease. Along with their Serbian colleagues they make up half of the pilots working for Services Air, a fast-growing Indian-owned cargo company that flies US and Russian planes around Congo.

In the city, a large part of Goma’s economy centres around the UN bases in town. Congolese hawkers sell pirate DVDs over the walls of a South African camp. In high-walled compounds, there are thousands of UN soldiers and staff from countries as diverse as India, Malawi, Uruguay and Senegal. Armoured personnel carriers park in convoys outside restaurants and UN aircraft flown by Russian pilots drone overhead all day.

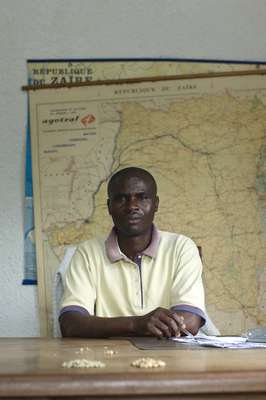

Not everything in Goma revolves around gold, girls and the shady gun-runners and diamond-smugglers that were once a staple in the city. Michel Mwengeherwa is interested in what he calls Congo’s green gold – coffee. Throughout the 1980s, the firm that Mwengeherwa manages used to export more than 320,000 sacks of high-quality coffee a year to Europe. Nowadays, they are lucky if they ship 6,000 sacks at most.

Given that neighbouring Rwanda and Uganda make millions of dollars from coffee, the collapse of the local industry is all the more galling. If only investment could be found to update the ageing machinery, Mwengeherwa says production could outstrip even the good old days.

In the centre of town, Lebanese entrepreneur Bilal Bakri, 37, has a burgeoning business empire. Part of an age-old Shiite Lebanese community in Africa, for a year he has been the owner of Kivu Market, where you can pick up tins of escargots from Indonesia, crab meat from Chile or fresh croissants. In the next few months he plans to open a Lebanese takeaway, 24-hour pharmacy and beauty salon.

Six months ago Bakri also bought a factory for bottling mineral water from Lake Kivu. Now, it is being run by his 20-year-old cousin, Hassouna, and produces around 300,000 bottles a month. But the waters are not only good for drinking. Due to a quirk of tectonic shifts and the presence of a unique bacteria, there is about 60 billion cubic metres of methane gas in the lake. On the Rwandan side, the KP1 project, which will extract the gas and turn it into electricity, is under way.

Given that Congo has an equal claim to the lake and its methane as Rwanda, if peace really does come to this region then it’s just one more resource that could make Goma as rich as it could be.

Ten ways to make money in Goma

1. Minerals: From gold to coltan, Goma is near one of the world’s richest mineral regions. 2. Tourism: Goma is on the edge of Virunga National Park, with gorillas, volcanoes and beautiful Lake Kivu. 3. Coffee: While Rwanda and Uganda have turned coffee into their top export, trade has dried up in Congo. 4. Hotels: Catering for journalists, aid workers, businessmen and tourists alike 5. Nightlife: Living on the edge isn’t always easy. Come night time Goma’s bars are heaving with expats. 6. Transport: Moving anything by road is a bad plan so air cargo services are flourishing. 7. Shopping: With low or no import duties, Goma is a regional market for cheap imported goods. 8. Supermarkets: Catering for the varied tastes of Goma’s wealthy visitors. 9. Methane: Millions have already been invested on the Rwandan side of Lake Kivu in a project to harness its methane. 10. Construction: The mineral-fuelled boom is making people rich and they like to show it off.

Made in Goma

Goma doesn’t offer much in the way of tourist trinkets or crafts ready for export. But with their entrepreneurial genius, the Congolese have somehow turned even the symbols of Goma’s tragedy into simple souvenirs.

- Fresh maracuja juice (or passion fruit juice). A staple at bars around town.

- Kivu Maji Mineral Water. Bottled from the crystal clear depths of Lake Kivu and sold by a local Lebanese-owned company.

- Model UN vehicle made of scrap metal. UN fighter helicopters also available.

- Lava stone gorilla statue. After the nearby Nyiragongo volcano covered Goma with lava in 2002, it was only a matter of time before some bright spark saw a business opportunity.

- Arabica coffee beans. Produced by the Nyiragongo coffee company (named after the volcano that destroyed half the town).

- Supermatch cigarettes. Manufactured in one of Goma’s most modern factories by a Congolese firm using tobacco grown locally. Not the best quality – even seasoned smokers find them difficult.