Essential air services / Global

Remote control

Playing a vital role in linking isolated populations to the outside world, these three airlines are reliant on subsidies, making their existence contentious. But for the wounded rancher or long-distance oil-worker they are indispensable.

Public subsidies for private companies can be a hard sell; even more so in the wake of the global financial crisis when every penny of government spending is being carefully scrutinised. And while there appears to be an acceptance that road, bus and rail networks are worthy recipients of public largesse, aviation is often dismissed.

Yet for many remote communities in the US, Australia and the UK, a flight that connects them to a bigger city can be a lifeline, from the accountant-pleasing encouragement of investment to the more uplifting effect of bringing friends and families closer together. But a flight from Cardiff to Anglesey in Wales, Billings to Sidney in Montana or a eight-stop milk run linking tiny towns in Queensland, Australia, are never going to make a profit.

The only way that they can survive is if the government provides a subsidy. Such schemes are under pressure more than ever before but as these reports suggest, a little public money can go a very long way.

1

Regional Express

Queensland, Australia

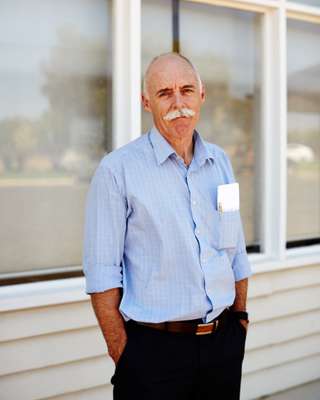

Some 10,000 feet above the Simpson Desert, Regional Express’s Saab 340 passenger plane skips over the untamed plains of Australia’s outback. It’s 46.5c outside and plumes of hot air emerging from the sands below ferociously rock the 36-seater aircraft. Yet on board the mood is relaxed; it seems a few knocks aren’t going to rattle the passengers making use of this unique air service. Among them is cattleman Colt Foley; in frayed cowboy garb he is returning to work from a Brisbane hospital.

“I’d mounted a fresh horse and he got spooked, went into full gallop and then threw me off,” Foley says, explaining his injuries. “I had to get back on though and finish the day, I’ve been a cattleman for a long time and you just learn to manage this kind of thing.”

Now recovered from a damaged spleen and cracked neck vertebra, Foley has hopped on board this Regional Express service to return to mustering cattle at Tambar Station, a 9,250 sq km property (almost Cyprus’s landmass) in rural Queensland. Foley’s hardy attitude is mirrored across a diverse cast of outback characters on board the Queensland state government subsided route, a eight-stop long-haul flight skirting Australia’s Red Centre. Twice weekly this flight snakes from one remote community to another, dropping off and collecting passengers, mail and medical supplies before returning to Queensland’s state capital, Brisbane.

“Aviation plays a big role in connecting communities and individuals across the state – it’s critical,” says Queensland deputy premier and transport minister Jackie Trad. Her vast portfolio includes maintaining a road infrastructure that, if laid straight, would make a return trip to London. “The government supports a number of regulated routes to guarantee remote communities that there will be an aviation service to connect them, at a capped price, to essential services.”

At 2,032km the Western 2 Route, as the “milk run” is officially known, is one of the longest of the five regulated routes piloted by Regional Express, which connects isolated communities from the tip of Cape York all the way down to the New South Wales border. On board, the small cabin echoes with relaxed conversation – turbulence during the nine-hour flight is laughed off by miners, farmers, health workers, visiting relatives and the occasional curious tourist.

Regional aviation in Australia has struggled over the years as outback populations migrate toward the greener areas and larger metropolises. Regional Express – a small, partly Singaporean-owned airline – runs a fleet of Saab 340s and specialises in this type of grunt country work. While propped up by offshore financiers, the business is very much attuned to outback travel. It has a specialised training facility for bush pilots in the regional town of Wagga Wagga and encourages all staff members to be ambassadors for rural Australia. But even for Regional Express, providing a service for the dwindling communities found in these drought-ravaged regions in western Queensland can only happen through government support.

“This flight is essential,” says Andrew Cameron, director of nursing at Birdsville Health Clinic. “We get all our medicine from the plane and blood samples from the lab. We are on the front line here.”

Cameron says that outback aviation – while still bumpy – has improved since the days when he would hurtle along the runway in his ambulance on a “roo run”, clearing marsupials resting on the bitumen. Today, government funding keeps the airports fenced and well managed by the local councils.

But besides managing rogue kangaroos at its airport, the Barcoo Shire council at Windorah, stop number four, is tackling a much more intangible problem. Congregated at the unofficial town hall, the Windorah pub, they discuss the three-year drought plaguing the citizens of the tiny towns in the community and the graziers that run cattle across their vast dry surrounds.

“Once the rains come and add water to this country it is a very rich and productive area – probably one of the most untouched productive areas in the world,” says Barcoo Shire council chief executive officer Robert O’Brien. “She’s very good in the good times but she’s bloody terrible outside of those times.”

Right now the community is enduring more trying times. With the Shire’s viability largely drawn from cattle and its young population dispersing, there’s an increasing push toward the diversification of local industries. Barcoo Shire mayor Julie Groves remains optimistic about the region’s future, noting that resourcefulness has always defined outback communities.

“If there’s one word to describe the character of the people out here, it’s tenacious,” she says. “It’s being tested at the moment but you have to stay positive.”

2

Links Air

Anglesey, Wales

Something very un-British takes place on the 40-minute flight between the remote Welsh island of Anglesey and the nation’s capital, Cardiff: people talk to each other. “You do become a bit of a regular,” says Karen James-Watkins, ceo of Enterprise at the National Museum Wales. With only 19 passengers on board, the seven-row plane often carries familiar faces who greet each other as they fasten their seatbelts.

The cosy on-board atmosphere is enhanced by Links Air co-pilot Paul Davey. In addition to welcoming passengers he picks up their carry-on with a smile and stuffs it in the tiny cupboard by the plane’s entrance. He even gives the safety briefing before taking his position in the cockpit that’s open for all passengers to peek into. “I love this route,” he says. “You get to know the regulars so you can get some banter started.”

Travelling once a month since the service began in 2007, passenger Paul Eastment, operations manager for lifeboat charity rnli, is grateful for the flight that spares him an almost five-hour drive from Cardiff and at an affordable price, too. “The fact it is so cheap is a massive benefit for us,” he says. “Being a charity, the more cost-effective the better.”

Eastment’s return flight from Cardiff to Anglesey costs £30 (€42) thanks to a hefty subsidy from the Welsh government. Without it, Links Air wouldn’t be able to afford this twice-daily connection. The subsidy is not without controversy but Edwina Hart, the Welsh transport minister, says the benefits are worthwhile. “For historic and geographical reasons, travel by road and rail between north and south has been relatively time consuming. The Cardiff to Anglesey service generates positive economic-development outcomes for northwest Wales.”

Anglesey needs all the help it can get. Connected to the rest of the country only by two small bridges over the Menai Strait, the sizeable but not densely populated island has had to rely on its own devices to create work for its residents. After the local aluminum factory shut its doors in 2009 with a loss of almost 400 jobs, Anglesey forfeited one of its main pillars of employment. Since then the community has banked on sheep farming and tourism to keep afloat, including Britons coming to surf the unruly waves ruffled by the strong winds battering the island’s rocky bays and gorse-covered hills. The wind has also begun to attract energy companies. Plans to develop what would be Europe’s largest offshore wind farm haven’t yet got off the ground but the Welsh government still hopes to turn Anglesey into “Energy Island”.

For now, Anglesey’s economic future remains reliant on its connections to Cardiff and beyond. The small twin-prop aircraft will continue flying back and forth twice a day from this remote Royal Air Force base; the passengers will continue to talk to the people sat next to them and – despite an atmosphere of government cuts – the subsidy is likely to remain.

3

Cape Air

Montana, USA

On a frosty morning, seven passengers troop from the airport terminal in Billings, Montana, towards a Cessna. They are seated according to their weight to ensure the plane is correctly balanced and the pilot, Sam Lyman, swivels round in the cramped cockpit to give a pre-flight talk. “There are flotation devices underneath each seat,” he says, before observing that central Montana is not a particularly watery place.

The destination is Sidney, a town in the east of the state where life has been turned upside down by the Bakken fracking boom. Like scores of other routes across the US, the Billings-Sidney flight is subsidised by the federal government as part of a contentious programme called the Essential Air Service (EAS). It costs more than $250m (€225m) a year and was instituted in response to the airline deregulation of 1978, when the government lost the authority to decide where airlines flew. There were fears that without incentives, small communities would be cut off.

“Montana is a poster-child for why EAS exists,” says Cape Air manager Erin Hatzell.

Without the Sidney flight there would be a drive of about 435km, or four hours, for the oil workers, medical patients and others who take it. Tickets cost $52 (€48) and for each one the federal government paid a subsidy of $172 (€150) in 2014. Critics call EAS a boondoggle and there have been attempts in Congress to eliminate it. It’s not as if those needing to get to Sidney don’t have other options: the town of Williston, only 73km away, offers unsubsidised (albeit pricier) flights.

As the plane dips beneath the clouds, Sidney is revealed: a tiny place girded by the Yellowstone River and bluffs. Driving through town, its transformation is obvious. There are 10 new apartment complexes and six new motels according to the mayor’s office and in the past four years the town’s population has almost doubled to about 9,500. Among the dated-looking bars downtown is a craft brewery with exposed brick walls and espresso served until 11.00. “One of the things I’m really disappointed about is this health clinic, which used to be a doughnut shop,” says oilman Philip Riely with a smile.

Elsewhere he points out the reasons for the change: oil wells. “This is what we call a man-camp,” he says, indicating an untidy agglomeration of trailers where workers have to live because every bit of property in town is taken. “There was a lot less garbage when we had fewer people,” he says.

Over at City Hall, Sidney mayor Rick Norby, who rents cars in addition to fulfilling his political duties, explains the downside of the boom. Oil revenues mostly go to the state, not his town, but he’s the one who has to deal with the population pressures. “I’d hate for anyone to think we’re this happy town that has all the money,” he says.

Sidney can’t afford enough police or rubbish trucks, or to maintain roads effectively. Traffic incidents are up significantly and, worryingly, domestic violence reports are up 700 per cent. “Sidney has lost its innocence,” Norby says. “You’ll see people walking in pairs.” The problems are exacerbated by falling oil prices, meaning Sidney receives even less revenue than before. “No matter what happens we’ll get through it,” he says. “We don’t want to lose that small-town atmosphere.”

Norby credits the EAS flights for helping turn Sidney into a regional hub, though he wishes the city received bigger aircraft. As it happens, Sidney is Cape Air’s busiest route in Montana with five daily flights; the other four outlying towns it serves in the state only get two. As Monocle wraps up its day in Sidney there is a phone call: the return flight to Billings has been cancelled. To be fair, this is an uncommon occurrence on the route, caused by a pilot shortage. At any rate, the long taxi ride back to Billings through a deserted landscape and under a vast sky, does not feel like a hardship.