Animators / Global

Reel deal

A slice of fairytale magic could be yours for €50,000 for a 30-second commercial or a cool €200m for a blockbuster – but where is the heart of animation in 2016? From paintbrushes to computer screens, we profile a superpower and the pretenders waiting in the wings.

There’s a cartoon – sorry, animation – doing the rounds that features all those Disney icons from our infancy. But instead of the hand-drawn imagery of yesteryear, these characters have been brought crashing into the 21st century. The reason? Computer Generated Imagery (CGI).

Some say the prevalence of computer-drawn digital imagery is stripping the industry of individual creativity. But animation-studio giants such as Pixar are proving that technology can be harnessed to create the most detailed animation we’ve ever seen (it doesn’t have to look like a computer game if you don’t cut corners). And small studios from Japan to the UK are also finding an audience.

Spanning films, advertising and music videos, this is a world of attention to detail where drawing, painting and moulding still exist. We’ve visited the large and the small to find out what’s shaping up for 2016. The future of animation may not be so much about the techniques but the ability to tell a funny, clever or moving story; achieve that and you’re on your way to winning over the audience.

1- Pixar

Emeryville

Wander around Pixar’s campus in Emeryville, northern California – yes, this is a “campus” – and you could be forgiven for thinking you were in Silicon Valley. Near the giant outdoor artwork of the company logo – a desk lamp – young employees flow in and out of the glass-doored Steve Jobs Building (the Apple man was one of the original founders). Nearby a vocal lunchtime game of basketball is taking place, while the more disciplined are doing lengths in a swimming pool that is neatly divided into lanes.

When it comes to animation, Pixar’s opuses trip off the tongue. The studio has been making a name for itself ever since its debut feature, Toy Story, in 1995; skip forward to the present day and the list of household-name films has swelled to Finding Nemo, Wall-E and many more.

Pixar is undoubtedly pioneering – and it’s set to continue in that vein. With its glimmering complex and membership of the Disney mega-family since 2006, it’s hard to imagine what it was like pre-Toy Story. “We had been on a shoestring budget for so long,” says lighting and photography director Sharon Calahan. “I had a third-hand desk that was falling apart and my chair didn’t have arms on it because they had broken off. Now we have a lovely campus and free cereal!”

While CGI has replaced hand-drawn movies, Pixar is stepping it up a gear and seeing how far it can push technology to remain at the forefront of animation. The stats for The Good Dinosaur, released in the US at the end of November 2015, are revealing. More than 900 effects shots in the film – a typically Pixar tale of a dinosaur who acts like a boy and a boy who behaves more like a dog – included work from by far the largest effects team on a Pixar film. “We’re all perfectionists,” says effects supervisor Jon Reisch, whose wife also works at Pixar. “You spend years on a film and we’re looking at really detailed minor points.”

While the animation business undoubtedly requires individuals with an obsessive personality and an ability to lock themselves in dark rooms for long periods of time, Pixar takes it to a whole new level. The effects team constantly has to pore over minute details, from creating a realistic CGI wine-pour action in Ratatouille to making sure the rapids and crashing waves of an angry river look realistic in The Good Dinosaur.

But it is the scenery in The Good Dinosaur that gives the clearest indication of where Pixar is heading in 2016. Modelled on parts of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and Utah, the team downloaded 167,000 sq km of US geographical data and created a virtual set. They then zoomed through the area on a computer – CGI film scouts – and decided where they wanted to put their virtual camera. It was the first time such a detailed endeavour had been attempted.

With about 400 staff members contributing to any one film, which can take several years to complete, the number of departments and stages the film has to go through is overwhelming. And yet despite the protocols in place, Pixar president Jim Morris argues that the studio is old-school in many ways. “People here are staff as opposed to the majority of the motion-picture business where you go from project to project at different studios,” he says. “So we’re almost like an MGM of the 1930s or 1940s.”

Pixar seems to instil fierce loyalty and a desire to stay put but the studio isn’t resting on its laurels. It’s starting to slowly shift the emphasis away from founding directors such as John Lasseter to a younger generation that includes first-time director Peter Sohn. “I know it sounds trite,” he says with an earnest expression, “but there are a lot of people here who love making movies.”

Although with each of those people producing as little as five seconds of animation per week, it certainly seems like a tough kind of love.

pixar.com

2- Tonko House

San Francisco

Robert Kondo is enthused. “This is the most exciting time to be in animation since we started working,” says the Tonko House co-founder. “There is a need for content everywhere.” And indeed, that hunger for animation has kept the fledgling studio that he set up with Dice Tsutsumi in 2014 solvent ever since.

The founders – both former art directors at Pixar – are finishing production on a 13-minute short called Moom. The pair hope that the film, based on a Japanese children’s book, will be touring the festival circuit in 2016. They’re also working on a CGI feature-length spin-off of their debut hand-drawn and painted short The Dam Keeper; it and an accompanying graphic novel are both in the planning stages.

With only four full-time staffers their set-up is different from the “old Hollywood model”, says Kondo. Mixing hand-drawing and CGI, Tonko House has the dexterity of a small company but also the challenges of cementing distribution and working with outside production

staff. Yet Tsutsumi believes Tonko House – an amalgamation of “pig” and “fox” in Japanese, characters from The Dam Keeper – is in a unique position. And with Netflix expanding its animated content in 2016, both founders feel that new online distribution channels will only help studios such as theirs. “We want to share the journey,” says Tsutsumi.

tonkohouse.com

CV

Founded: 2014

Staff: 4

Paintings created for 'The Dam Keeper' Short: 8,105

Pages in 'The Art of The Dam Keeper' Book: 168

3- Oh Yeah Wow

Melbourne

Darcy Prendergast has to think a little. He’s pretty sure that his Melbourne-based studio was formed in 2011 and has about 20 workers but it’s hard to know for sure given the flow of freelancers through the warehouse space in the Brunswick neighbourhood. However, business was never the major driver for setting up Oh Yeah Wow. “I didn’t want to have to work on somebody else’s feature film ever again,” he says with a chuckle.

Oh Yeah Wow is a hotchpotch of creative ideas spanning live action, stop motion and hand-drawn 2D animation, covering everything from advertising to music videos. And the results are always interesting. Indeed, you get the feeling that Prendergast and his colleagues are doing what they love best and carving out a niche for themselves along the way.

Prendergast talks about a “gap in the market”, given the lack of global stop-motion studios. Current and forthcoming projects include a cartoon series for Nickelodeon Australia called Supa Phresh, about three mutants in a supermarket universe; then there’s personal project Pongo, which uses clay stop-motion and focuses on the plight of orangutans in Sumatra. Monsters Playground, another stop-motion film, is set for release in mid-2016. The secret of the studio’s success? “We’re really good at storytelling,” says Prendergast.

ohyeahwow.com

4- Calf Studio

Tokyo

Mention Japanese animation and most people will assume you’re referring to anime, from the epic big-budget films of Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli to Pokemon cartoons and dystopian robots-in-space movies.

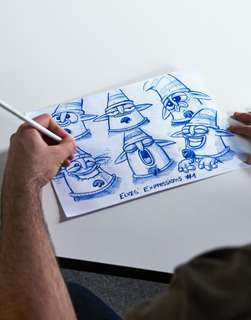

Calf Studio’s work doesn’t belong in this category. The small Tokyo-based independent outfit, formed in 2010 by three Japanese film-makers and a film critic, is known for animation that’s drawn by the artists, frame by frame. “It’s labour intensive,” says Kei Oyama, one of Calf’s co-founders. “There are 24 to 30 frames in every second of a film and you get distortions in each one. But that’s what makes it unique.”

Calf’s small office is located in an old building in central Tokyo. Early on the aim was to bring attention to the work of the collective’s film-makers – Atsushi Wada, Mirai Mizue and Oyama – through screenings at festivals overseas, art-house theatres in Japan and limited DVD releases.

Oyama, 37, is the only original member left and he has taken Calf in a more commercial direction. Recently the studio has worked with independent artists and film-makers on TV shows for public broadcaster NHK, educational publisher Benesse and big multinationals.

The studio’s speciality is adding movement to paintings and drawings. It evolved from a project Oyama and Wada worked on before Calf’s launch: in 2008, they brought a comic strip about manga artist Shigeru Mizuki to life for a feature film that was more zoetrope than Pixar.

Soon Benesse was asking them to work on TV show Shimajiro Wow!, which had more than a dozen animated shorts, each with a different artist. “Japanese anime mostly comes from printed manga; rarely do they start as illustrations. We felt there was potential for more variety and we wanted to surprise people,” says Oyama.

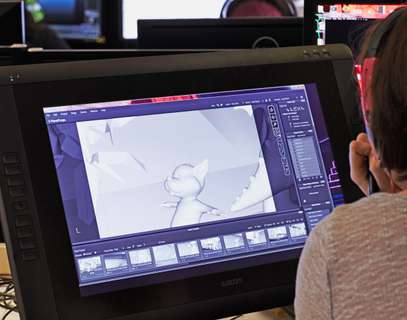

In Calf’s office six people – most of them students from Tama Art University, working part-time – are adding colour to digital sketches on touch-screen computers for a cartoon called Dochamon Junior. The five-minute programme has aired on NHK every week since October and to create one episode takes about 10 days.

The budget is small and Calf doesn’t expect big profits from the five-month gig. But the creative freedom and the chance to reach a mainstream audience were too good to pass up. “The offer came from the broadcaster, not through an ad agency, which is typically the case,” says Oyama. “We brainstormed with NHK on the story but animation decisions are left to us.”

On the screen next to Oyama’s, Shin Hashimoto pulls up a scene from another project. Boku no Bambi (My Bambi), a film that follows a screwball schoolboy, is one of several original stories Calf has in the pipeline for 2016. It’s reminiscent of the offbeat and absurd films that have earned Calf awards at Annecy International Animation Film Festival in France, the Fantoche International Animation Festival and Animafest Cyprus.

The awards never did much for the studio in Japan, where its commercial work comes from. So in 2013 Calf’s original members split up, leaving Oyama to restructure the studio. He still calls on his old partners for jobs but has stopped organising screenings and producing dvds. Calf’s reputation has spread to the point where requests for screenings of the studio’s work from festivals in the UK, Australia and Italy are trickling in; Oyama will start releasing work online soon.

The studio makes just enough to commission one of its own 10-minute films each year. Oyama’s dream is to do a full-length animated feature but for now he’s happy to challenge mainstream perceptions about Japanese animation. “There are a lot of artists here whose work is bizarre but they would do amazing commercial work if somebody could connect them to ad agencies and media companies. We can do more of that.”

CV

Founded: 2010

Annual revenue: ¥40m (€300,000)

Staff: 4

Type of animation: Drawn or painted by hand

Types of media: Shorts, music videos TV and online ads, animated TV shows

Forthcoming films: 'Dochamon Junior' (2015/16), ‘Boku no Bambi’ (2016/17), ‘Keiichi Tanaami Art Exhibition’ (2016), ‘Eikoh Seminar’ (2015/16)

5- Job, Joris & Marieke

Utrecht

Joris Oprins met co-founders Marieke Blaauw and Job Roggeveen when they studied together at the Design Academy in Eindhoven. While they were meant to be designing chairs and water coolers they discovered their interests lay elsewhere. “We tried to tell stories with products at the beginning but that didn’t work,” says Oprins. “Then we started making shorts and they let us as long as we made some products occasionally.”

The friends are still working together – now in an unflashy, utilitarian space in Utrecht – producing adverts, music videos and short films. Oprins and Blaauw have a five-year-old daughter together, Aagje, who helped inspire their film Otto.

“When we were in Los Angeles lots of people told us they would love to have a three-person studio,” Oprins says. “You’re not a small part in a big film but a huge part in a small film, something we prefer.”

Oprins is, of course, being modest. The reason he was in California was because the studio’s 2014 short, A Single Life, was nominated for an Oscar. The trio admit they have to be careful that the attention and desire to expand doesn’t cause them to lose their winning formula. But Oprins denies they’re on the road to becoming another Pixar. “We’re more stylised and have slightly weirder characters.”

jobjorisenmarieke.nl

CV

Founded: 2007

Size of studio: 60 sq m

Staff: 3 (plus freelancers)

Type of animation: CGI

Types of media: Shorts, music videos, adverts, feature film in planning stage

Forthcoming film: ‘Kop Op’, 25-minute film (October 2016)

Length of 'A Single Life':: 2 minutes, 15 seconds

International awards won: 29

6- Daisy Jacobs

Gosport, UK

When it comes to animation Daisy Jacobs thinks big, which makes it appropriate that her breakthrough film – a Bafta-winning short – should be called The Bigger Picture. Shunning diminutive traditional sketched animation, small clay models and the constraints of a computer screen, her animation is life-sized – a technique that throws up its own set of challenges.

For the Hampshire-born film-maker, recreating her characters in such epic proportions actually makes the job of animating easier. “It’s a much more physical way of working and I think you end up connecting more with the characters,” says the 27-year-old.

Not that she is making life easy for herself. The scale of her work makes it expensive as she has to rent a large studio space and invest in lighting and camera equipment. To create her animation Jacobs dons her overalls, gets out her brush and paints characters on a wall, making them 3D with papier-mâché. She then uses props such as tables, chairs and pictures to give the scene a surreal realism.

With 24 frames in a second, Jacobs may have to repaint the wall the same number of times just to create a second of footage – a time-consuming endeavour. “If we’re doing something big we can probably do two seconds – so 48 frames – in a day,” she says, laughing. The more complicated a scene – walking, talking and with 3D objects – the longer it takes.

With her contemplative responses and self-declared mission to create films that are “worthwhile”, Jacobs comes across as the antithesis of the big-name studio. Hers is stripped-down work that she writes, storyboards and designs on her own, only combinging with a team of people when it comes to physically putting the film together – and she works with just one co-animator, Christopher Wilder.

Operating this way has its advantages and is the only way she can see her future right now. “It’s as individual as something can be,” she says. And it makes sense: Jacobs retains creative control.

The Bigger Picture – an equally funny and sad story of two brothers dealing with their ageing mother and inspired by the death of Jacobs’ grandmother – was the film-maker’s MA project when she was studying directing animation at the National Film and Television School in Buckinghamshire. She had no idea it would get the reaction that it did, winning a Bafta and becoming an indie-festival favourite. That success has catapulted her into the limelight and set her up for an illustrious career.

With the awards money, an online-funding campaign and cash from an organisation (“I don’t think I’m allowed to name it,” she says), Jacobs is now making her next film in another giant studio space in Gosport. “It builds on what we did in The Bigger Picture,” she says. The name of her third film has recently been announced as The Full Story (her debut was the two-minute Don Justino de Neve) and will be ready for release by the end of next year.

Until then Jacobs promises to turn up to the studio every day, armed with her set of paints and brushes, and do what she does best: bringing her life-size characters into being and creating a really rather clever story along the way.

thebiggerpicturefilm.com

CV

1988: Born in Hampshire

2009-11: Undergraduate in illustration at Central St Martins

2011-12: Postgraduate in character animation at Central St Martins

2012: Bafta scholarship to study at National Film & Television School (NFTS)

2012-14: Masters in directing animation at NFTS

2014: Release of 'The Bigger Picture'

2015: Wins Bafta for Best British Short Animation

2016: 'The Full Story' to be released at end of year

7- Blue-Zoo

London

The offices of Blue-Zoo have all the trappings of a creative space: mandatory table football, colourful posters on the wall and someone using an exercise ball as a chair; even the walls on the third floor have been turned into doodle-covered blackboards. But the aesthetic is not merely symbolic: real creativity happens here, manifesting itself in a hushed silence. The team is knee-deep in a new project: “Digby Dragon,” says co-founder Tom Box excitedly. “It’s a 52-episode TV series. Just look at the quality of the animation.” He shows us a feathery-looking character, one of Digby’s companions; the detail is so intricate that young viewers will be able to see every aspect of his plumage.

This small studio off Great Portland Street in London has 130 employees yet it has already garnered three Baftas and worked with everyone from Microsoft to Disney. Its beginnings, however, were much more humble. Computer-animation classmates Oli Hyatt, Tom Box and Adam Shaw founded Blue-Zoo at Bournemouth University in 2000. “Oli sent an email around the department asking, ‘Who wants to start an animation company?’” says Box. It was as simple as that.

The newly formed trio didn’t have to wait long before their first commission: creating a cartoon character for the BBC, prophetically named Blue Cow, who travels around the countryside on a red double-decker bus and embarks on all sorts of misadventures.

The studio has broadened its horizons since then, producing adverts, visual identities and corporate infographics, as well as TV series; its overall success derives from the latter. When the team started out 15 years ago, animated TV was an unorthodox trade and CGI existed only in feature films; even the BBC hadn’t ventured into animation. Today the humour, creativity and quality that brought Blue-Zoo success in children’s TV has trickled down to the rest of its work. “We can apply our high-calibre tools and expertise from long-form animation to our commercial work, which means we can produce high-quality, engaging commercials in a short time,” says head of services Damian Hook.

Blue-Zoo is growing fast but the team doesn’t want to lose its small-studio mindset. “It means you have creative freedom,” says Will Cook, a lead animator. Part of their strategy is promoting the studio’s sense of “Britishness”. With the animation industry dominated by US funding and production – even for a film as seemingly British as Paddington Bear – Blue-Zoo is keen to start making in-house big-screen efforts and compete with the US animation industry.

“We want to address this imbalance and work is underway,” says co-founder Hyatt. “We’ve won funding from the British Film Institute to produce our own feature films.” Now all they have to do is track down a decent screenplay.

blue-zoo.co.uk

Q&A

Tom Box & Oli Hyatt

Co-founders, Blue-Zoo

How do you make Blue-Zoo stand out from other animators?

TB: A combination of quality and making sure that our work has personality to it. We have a cheeky sense of humour and that’s what shines through.

What is your most memorable project?

TB: A few years ago we animated the Rolling Stones gorilla for the band’s 50th anniversary. Seeing our work on-stage at Glastonbury in front of 100,000 people was mind-blowing.

Why is there a golden postcard from the White House in your lobby?

OH: Olive the Ostrich, one of our cartoon characters that’s popular in the US, is a mascot for the White House Easter Egg Roll. Michelle Obama sends us thank-you cards every Christmas.

Which side of animation is the main earner?

OH: Creating a TV series because you can license them out and receive royalties for decades. Commercial work is great but it’s a one-hit affair; it doesn’t have years of profit.