Observations. / Global

Shifting sands

From the changing face of advertising to the fast-paced transformations of Tokyo, Beijing and Madrid, we lift the curtain on the issues, questions and events that have been shaping the world and will continue to resonate in 2019 and beyond.

In good health

The future of medicine

David Karow is an intense, wiry man who believes he is unlocking the secrets of the future. “I feel like the theme-park owner in Jurassic Park,” he says, as he leads us to the inner sanctum of his futuristic medical clinic outside San Diego. “Remember how the character says, ‘I’ve spared no expense’? Well, we’ve spared no expense.”

Karow’s clinic, Health Nucleus, offers the check-up to end all check-ups: not just the usual blood work and heart monitoring but a full-body MRI and, most importantly, sequencing of patients’ DNA to look for mutations, risk factors and early onset of disease that, Karow says, no other medical exam can match.

The service doesn’t come cheap. When it launched in 2014, the price tag was $25,000 per visit, although that has come down to $5,000. Patients, most of them high-level business executives, are treated to what Karow describes as a “spa-like” setting, complete with private waiting rooms, bathrobes and essential-oil treatments to ease the hour-long MRI.

The clinic certainly feels like a glimpse of the future, with its small army of medical technicians and genetic scientists. There’s software that shows sharp, beautiful images of the human heart beating and full-colour views of the brain from any angle. In a vast upstairs room, banks of gleaming white genomic sequencing machines boast enough processing power, Karow says, to map the DNA of “a medium-sized European country”. Following the tests, visitors are given a “personal health intelligence report” that provides insight on everything from cardiovascular and neurological health to food allergies and ancestry.

The clinic was founded by Craig Venter, a biotechnologist involved with the first sequencing of the human genome in 2000. He has been looking for ways to revolutionise medical science with it ever since but the venture has not been without its hiccups. Venter vastly overspent on the clinic; he and most of his original senior staff have left, trusting Karow, who took over in the summer of 2018, to find a way to make it commercially viable.

Karow acknowledges that Health Nucleus started out as “an artisanal science experiment.” Now he wants to partner medical schools and hospitals to grow the databank of patients well beyond the 3,000 who have come in so far. “We want the data to drive decisions, not superficial examinations,” he says.

About: Andrew Gumbel is a British journalist and author who has written for The Los Angeles Times, The Independent, The Atlantic and others.

Living longer: a brief guide

Move to the country

A Harvard study found that women living in areas with more open space have lower rates of mortality.Move to Monaco or Japan

Monaco’s elderly folk are the longest-living (and best maintained) in the world. But Japan is a close second.Join a choir

A study by the University of London found that singing releases stress-reducing endorphins and exercises the heart, lungs, abdomen and back.

Selling happiness

Let’s put cheer back into advertising

Once the advertising industry was a world of blissful happiness and clinking glasses in booze-infused boardrooms. The free-thinking spirit of this postwar, pre-computer golden era (so shamelessly romanticised by today’s side-parted, suit-wearing branding bigwigs) was a catalyst for creativity. And while we’ve thankfully moved on from much of the misogyny and misbehaviour that also ran rampant back then, we do miss the novel whimsy that also poured out of campaigns from a time when the creative director was king.

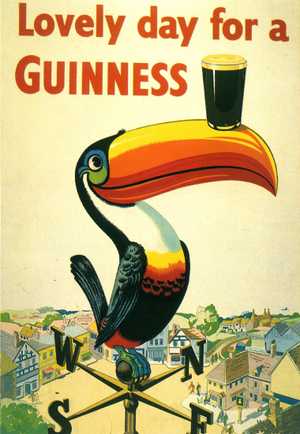

Air India, for instance, appeared a whole lot more enticing (on printed page, at least) when its charming cartoon mascot Maharajah introduced newly minted jet-setters to far-flung locations. And while Guinness still tastes as good as ever (and largely still does great advertising), didn’t its frothy form just look a touch more appealing balanced on a toucan’s beak on the famous 1950s “Lovely day for a Guinness” illustrated campaign posters? OK, sure, back then the products being so joyfully flogged weren’t going to make us happy in the long run (despite what marketeers told us). Yet the illustrated cockerel puffing a smoke in a 1950s Gauloises cigarettes poster by Switzerland’s Donald Brun still raises a smile, simply for its creativity.

So what happened? Well, health-and-safety regulators rightly curbed the creatives who were sanctifying the image of tobacco. But even the more savoury stuff seems to have been straightened up a notch. Only a few little iconic mascots like Knorrli (the slightly sinister-looking red-hooded character advertising Swiss food brand Knorr) still persevere. Even he, however, is now less prevalent in the brand’s messaging. Happiness as a naive and joyful emotion has been squeezed out of the brief by advertising agencies. And the reason? Well it’s us, the consumers, who are to blame.

Problems started when the people actually paying for the products got involved in the way that they wanted to be marketed to. Social media happened and brands suddenly became very attentive to us. Seducing a smile from an audience via a cutely designed billboard, poster or page ad is no longer enough. Now brands need to turn up the “engagement” and have a “purpose” – so maybe a turban-sporting mascot who could potentially divide opinion among the “audience” is no longer going to fly. For the record, the Maharajah temporarily ditched his turban in 2015 to don more internationally friendly garb. The aim was to make the brand feel more universal but we see it as a slight identity crisis.

Surely, in this era of hyper-awareness and sensitivity, we’ve all wised up to advertising being just what it says on the tin – advertising? Our kids certainly have, yet both they and adults can still be caught looking at it with complete glee. Case in point: the global phenomenon that became Melbourne’s Metro Trains’ Dumb Ways to Die 2012 safety-awareness campaign. Here happiness met the macabre in a frightfully cute cartoon that gathered awards and, most importantly, got kids off railway tracks.

Thankfully, in an industry where egos abound, advertising agencies are only going to kowtow to consumers’ wishes so much. Creative folk tend to be a strong-minded bunch and the good ones only pay so much attention to the zeitgeist. They continue to push companies to let them harness their creative craft in new and unexpected ways. And why shouldn’t they? After all, there’s no shame in popping a glass of stout on a cartoon tortoise’s back in the hope of cracking a smile (and selling some beer in the process).

Brands we like

Yamato Transport, Tokyo

A brand that’s intimate, humane and happy. Its simple image of a cat carrying a kitten is a clever metaphor in the otherwise dull world of logistics.Porter Airlines, Toronto

We can’t fail to mention the original Mr Porter, the cheeky, charming and popular raccoon mascot that our sister agency Winkreative developed for the Canadian airline.Herman Ze German, London

A restaurant that’s all about sausages but with a sense of the ironic. Its logo is smile-inducingly simple and blush-inducingly rude (depending on how long you look at it).

About: Australian import Nolan Giles is monocle’s Design editor. His idea of happiness is a few “frosty ones” in a second-tier Belgian city.

How we’ve reached peak brick

It’s time to ditch mock masonry

My first inkling that the back-to-bricks look had gone too far hit me like a ton of… well, never mind. It took place outside a dull branch of an unremarkable food chain at the base of a burly glass-and-steel tower in central London. The site’s fit-out, like many of the chain’s outposts, was adhering to a painfully strict set of brand guidelines. Through the window I saw carpenters hewing pale wooden shelving, electricians tinkering with head office-approved pendant lamps and a small mixer sluicing wet cement to just the right consistency to lay bricks.

In a glassy steel-beamed tower, you ask? Yes. And this modish take on brickwork is everywhere, from panels of brick cladding added on to new apartment blocks as an afterthought to carefully weathered (but brand new) feature walls in restaurants, galleries and god knows where else. Perhaps these exposed brick walls are meant to hint at the idea of craft or a back-to-basics aesthetic? An entrepreneurial do-it-yourself feeling that’s being felt from Brooklyn to Brisbane? Or is it just that laptop-toting freelancers are now demanding Chelsea-loft-conversion-style brick walls with their low-calorie decaf oat-milk mochas?

Whatever the reason, what started as a genuine money-saver (artists and upstarts didn’t always have money to treat their walls) or a crafty throwback has come to signify something more naff. Aren’t most exposed brick walls the modern equivalent of wood-effect wallpaper? The silliness is compounded when brick walls are retrofitted in full in glassy tower blocks or stuck onto buildings that don’t need them. So here’s a thought for out-of-ideas designers and architects: deconstruct that much-aped mock-masonry approach. It’s chilly, makes rooms noisy and isn’t sending the message you meant to. Likewise, popping panels of bricks on the outside of buildings smacks of a cover-up. Cementing an interesting brand identity, remember, needn’t involve cement at all.

About: Josh Fehnert is monocle’s executive editor. Despite being made of the things, his house in London features no exposed brick walls.

Tokyo’s game face

The Olympics are coming

On a sunny November day, in a lengthy process that called for years of experience and nerves of steel, Japanese engineers raised the roof – literally – on the new gymnastics venue for the 2020 Olympics. Journalists and construction workers watched as hydraulic jacks inched up a huge chunk of timber roofing. One misstep and 200 tonnes of carefully crafted Japanese larch could have come crashing down.

As night fell the roof section was finally in place, another piece in the puzzle of a unique building that is designed to showcase traditional Japanese building techniques. Work this meticulous doesn’t come cheap – the building has cost ¥20.5bn (€159m). Nor does it happen quickly (it should be ready by next autumn). Once complete it will boast the largest wooden arched roof in the world and seat 12,000 spectators.

Attention to detail is a Japanese trait that makes the country well suited to hosting an event on the scale of the Olympics. Preparations are at full throttle. Thousands of volunteers are being mobilised, the mascots have been unveiled and Olympic merchandise is on sale. Tokyo’s freshly minted taxi fleet – an eco-friendly Toyota hybrid in indigo blue – bears the 2020 logo and the city is festooned with banners and billboards.

The 2020 Games are the reason for everything from a spike in property prices to a long overdue curb on smoking. There was even talk of introducing daylight saving time for the Olympics to allow athletes to avoid the worst of Tokyo’s fierce summer heat (that plan didn’t work out but the marathon might still start at 05.30).

Apartment blocks and hotels are springing up while tourist figures are reaching numbers not dreamt of 15 years ago. By 2020, Japan is looking at 40 million visitors per year, a four-fold increase in little more than five years. The government is already encouraging companies to introduce teleworking to keep workers at home instead of clogging up roads during the Games. Construction is a feature of life in this relentlessly changing city but the Olympics has upped the pace and these days cranes hover all over. Kengo Kuma’s hulking 80,000-seater national stadium is rising in the middle of Tokyo. It will be even more striking once clad in its wooden lattice. The new Olympic venues are mostly clustered in Ariake, a spacious but unloved area of waterfront that has long needed a clear planning vision. The Olympics might finally make that happen.

No Olympic Games would be complete without its missteps: the original logo for 2020 had to be ditched once it was deemed to be too similar to a theatre in Liège, Belgium, and the planning stage of the national stadium was a tortuous saga. Few are thrilled by the astronomical bill for the Games either, currently estimated at ¥2.8trn (€22bn). There is still much to be done but if any city can pull this off with aplomb, Tokyo can.

About: Fiona Wilson is monocle’s Tokyo bureau editor, heading up editorial output from our shop-cum-office in Tomingaya.

Building on Brexit

Madrid’s urban makeover

Four storeys below ground, men in helmets and hi-vis jackets are gathered in semi-darkness, closely scrutinising a concrete pillar for cracks. There is a murmuring of agreement: it passes muster. They are standing at the foundations of Madrid’s newest skyscraper, Caleido. The structure has just broken ground and when it’s finished it will be a 35-storey tower with offices, retail units and classrooms for IE University. Caleido is just one development in Madrid that is expected to lure European businesses away from a stricken post-Brexit London.

Following the UK’s referendum result in 2016, companies in London’s financial districts have been looking to Europe in search of stable ground. Thousands of workers from the finance sector are expected to relocate to continental Europe due to Brexit. While Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Paris and Brussels are considered the frontrunners, Madrid is emerging as another quiet-yet-convincing contender.

When it comes to attracting talent, Madrid might be an easier sell than a northern European city. It has, on average, 58 days of rain a year, compared to Paris’s 164 and Frankfurt’s 111, while the allure of free-flowing sherry and tapas might entice more epicurean financial workers. But Madrid can’t market itself on quality of life alone according to José María Ezquiaga, dean of Madrid’s College of Architects. “Younger generations are prioritising the promise of a better lifestyle over inflated pay packets but big investors still look at the numbers.”

For years Ezquiga has been part of Madrid’s renewed push to attract skilled workers, acting as a consultant on the city’s most audacious development, Madrid Nuevo Norte. The sparkling new mixed-use suburb has been stalled for 24 years but is now earmarked for completion in 2024. “Truly global capital cities draw strength from innovation, knowledge and a vibrant social fabric,” says Ezquiaga. “Madrid boasts all of the above but it’s hamstrung by a slow-moving judiciary and bureaucracy.”

This may be the flaw in Madrid’s ambition to court businesses looking for a new European home. Today it takes about 13 days to get a business permit, although it’s a marked improvement on 2003 when it was 138.

As we ascend the stairs leading from the basement of Caleido, workers can be seen fixing metal rods into concrete to support the heavy structure about to rise in their place. It’s a useful metaphor: if you’re trying to create the most attractive financial and business centre in Europe, don’t forget the groundwork.

About: Liam Aldous is monocle’s Madrid correspondent. Read his happy take on his adopted home in most issues of the magazine.

Cash-free in China

Efficient for some, tricky for the rest

One minute I’m strolling into a metro station in Guangzhou; the next I’m stopped dead in my tracks by a bank of ticket machines that only accept payment by QR code and mobile phone. No cash, no credit cards, no kiosk to ask for help. The panic at missing my connection back home to Hong Kong only subsides when I discover the dusty slot machines hiding in quasi-retirement downstairs. As the country goes almost cashless, visiting as a foreigner is increasingly frustrating. China prevents anyone without a Chinese bank account or credit card from accessing essential payment services such as Alipay and Wepay. This is even the case for Hong Kongers: one country, two financial systems indeed.

Want to hail a taxi in Beijing using Didi, China’s equivalent of Uber? No chance. Fancy renting a bike in Chengdu? Don’t even think about it. Even paying for an ice lolly from a stall inside Tianzifang, a tourist spot in Shanghai, requires a QR code. In the past year or so I have faced an awkward after-dinner showdown at restaurants in each of these three cities when my card was declined and I was told that my roll of renminbi (the people’s money) isn’t acceptable tender.

Initially I refused to kowtow. Take the cash, I insisted, while borrowing the same stoic smile adopted by Chairman Mao on the red 100 yuan notes. China invented paper money, don’t you know. Waiters in Beijing would eventually relent and scramble together some change. Meanwhile, in Shanghai, my stubbornness didn’t work in a new European restaurant of all places, forcing me to fall back on the kindness (and credit) of my local dinner guest.

A working solution is to travel with a Chinese companion, rely on them to pay with their phones and then attempt to foist cash on them instead. Fortunately, Chinese hospitality is unrivalled. Visit China with a local and you may as well leave your wallet behind. However, this enforced economic dependency is limiting, ill-mannered and potentially ruinous: Chinese guanxi dictates that I must return the favour in Hong Kong so fingers crossed my mainland creditors don’t all visit at once. What’s more, relying on local largesse is not open to first-time visitors from faraway lands. The only absolute guarantee is to stick close to international hotels – hardly an authentic Chinese experience.

The global tourism industry is being upended by China’s high-spending tourists, who are venturing out into the world in high numbers. Nonetheless, the traffic is not all one way. More than 60 million overseas tourists visit China every year, placing it fourth behind France, Spain and the US (it would be top if Macao and Hong Kong were not counted separately). One travel-guide publisher I saw recently popped Shenzhen second on its list of cities to visit in 2019 – behind Copenhagen. China’s southern hub is home to technology giants such as Tencent – owner of WeChat and WePay – but good luck trying to tap into this increasingly futuristic city.

Finding a sympathetic ear on the mainland will be equally hard. Chinese tourists continue to face plenty of their own hurdles abroad: China’s passport ranks on par with Swaziland and only recently has UnionPay – its major credit card – become widely accepted internationally. But tit-for-tat retaliation is the language of trade wars, not tourism. As president Xi Jinping positions China as the champion of globalisation – for free trade and against tariffs – he should also open up the domestic digital economy to outsiders. More foreign trips to China can only be good for international relations in 2019.

About: James Chambers mans our Hong Kong bureau. Experiences in China aside, he’s usually happy to pick up the tab.

Sweet release

Turning on the waterworks

In a darkened room at a primary school in Tokyo, 40 mothers from the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) are watching short videos depicting love and heartrending loss. There are dying pets, weddings, selfless grandmothers and schoolchildren rising to a challenge. Before long all of the women are sniffling and dabbing at their eyes with handkerchiefs. I shift awkwardly in my seat. Then the last of the videos – a nappy commercial – begins and my eyes moisten. “How did that feel?” asks Hidefumi Yoshida from the front of the room as the lights flicker on.

Yoshida is known as the “tears teacher” and I’m sitting in on one of his two-hour seminars. He has made a name for himself as a guru of cathartic weeping. It’s a radical idea in a culture where self-restraint is a virtue. “We are told not to cry in front of others; at a young age boys are told they shouldn’t cry at all,” he says. “But people need to let it out.”

Before becoming the tears teacher in 2013, Yoshida taught English at a Tokyo high school. There, students often came to him with their problems. “They either got angry or wept. The angry ones kept coming back but the ones who cried didn’t. Crying seemed to solve a lot,” he says. A literature search led him to Hideho Arita, a Toho University researcher whose book, Techniques for Relieving Mental Stress, offered a scientific explanation. The two now teach courses as “tear therapists”.

These days Yoshida spends a lot of time hosting seminars in settings ranging from intimate gatherings at private homes to packed theatres with hundreds of educators. He’s been popular in the business sector since 2015, when the government made it compulsory for companies with more than 50 employees to have a stress-check programme.

Yoshida tells the assembled PTA mothers that he likes to cry at least once a week. He tells them to write down what moves them to tears. “If cat videos make you cry that’s what you should watch,” he says. After a few women share their stories, Yoshida has a tear-jerker about his own grandmother. By the end he’s sobbing. It’s a revelation for Kanako Kawasaki, a mother of two. “It’s reassuring to hear that we shouldn’t think of crying as bad or embarrassing,” she says. Her statement sets us all off again and the handkerchiefs come out.

Newest-age therapies

Letting it all out

Primal therapy, which involves expressing repressed suffering through the medium of anguished screams, is said to be a cathartic way of exercising one’s demons.Virtual therapy

Virtual-reality headsets are being experimented with as a way for people to overcome fears, from acrophobia to arachnophobia.Horsing around

Equine-assisted therapy involves getting up close with stallions and mares to build trust between patient and steed.

About: Kenji Hall is monocle’s Asia editor at large. He now understands the benefits of a good old cry.