Are Poland’s efforts to bolster its defences enough to deter Russia?

Faced with an increasingly aggressive Russia and mixed messages from the US, Warsaw is ramping up its defensive capabilities while preparing its people for the possibility of war.

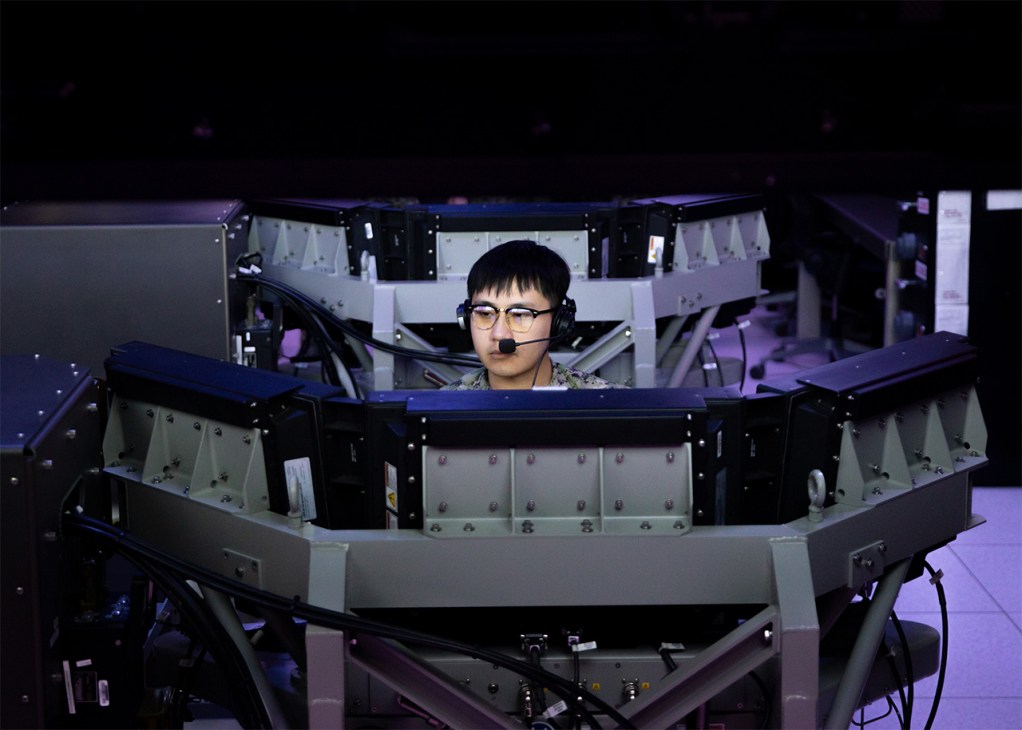

It’s a blustery day on Poland’s Baltic coast, where Monocle is being shown some SM-3 interceptor missiles. We’re at the Aegis Ashore Poland base and our US guides joke around as they open up containers housing 1.5-tonne rockets, which can travel through the air at speeds exceeding 4km per second. With the missiles out of their case, the mood becomes more serious. “We have the capability to defend all of Europe,” says Captain Michael S Dwan, who is overseeing the command of the base at the time of our visit.

The opening of Aegis Ashore was also a stormy affair. First mooted in 2002, the base became a source of tension between the US and Russia – the latter seeing it as a major provocation, despite what Washington and Waraw insisted were purely defensive capabilities. When it was finally declared active 22 years later, during the dying days of the Biden administration, Warsaw had good reason to feel vindicated for the decades spent lobbying the Americans to build it.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moscow’s aerial assaults on the country have sometimes spilled over into neighbouring Poland. In September, Russian drones made it as far west as Olesno, with Nato jets scrambled to shoot them down. Aegis Ashore, then, is a key pillar of Poland’s military deterrence, founded on both a centuries-old suspicion of Russia – a nation that has invaded on several occasions – and a post-Cold War alliance with the US. When the base opened, America’s commitment to Polish and European defence appeared unshakeable. But now there’s a very different president in the White House. Donald Trump has made no secret of his intention to pare back the US military presence on the continent and has even to defend its Nato allies in the event of an attack. The fact that US reticence has come at a time of Russian belligerence is particularly concerning for Poland.

After the end of communist rule, Warsaw went all in on the transatlantic alliance, cosying up to successive US administrations in a bid to establish a permanent American military presence in the country. Today there are about 10,000 US troops stationed here. But given the geopolitical climate, Warsaw has had to seek alternatives. In just two years, it has become Europe’s largest military spender as a percentage of GDP and built the continent’s biggest land army. Poland’s defence budget has increased by 50 per cent since 2023; while in 2024, it commanded 205,000 military personnel – third only to the US and Turkey (countries with far greater populations) among Nato member states. But with Vladimir Putin hovering and Trump wavering, the question remains: is it enough?

When Monocle speaks to veteran politician Michal Kaminski, he’s clear that warm relations with the US are still essential to Poland. “Being anti-American is impossible,” he says. “There’s a feeling that our liberation in 1989 was thanks to the policies of Ronald Reagan.” Yet behind closed doors, contingency plans are being made. “Though it can’t be declared officially, there’s a growing scepticism about America among Poland’s political elite,” says defence and security analyst Tomasz Pawłuszko. Such scepticism, born of a history of invasion by larger powers, is what has fuelled the recent military expansion. “The first thing that you need to know is that the Polish people are prepared to face Russia, even alone,” says Pawłuszko. “I wouldn’t have even begun to imagine it during the Biden administration but this is the style of political thinking that we have adopted.”

In 2025, Poland will spend almost 5 per cent of its GDP on defence, the most among Nato countries, including the US. The country is also debating a law to allow Polish forces to shoot down (without prior Nato or EU approval) Russian objects flying over western Ukraine. “Poland is, along with Finland, among the best [militarily] prepared countries in Nato,” says Pawłuszko. “We have the biggest army on the eastern flank and good co-operation with our biggest allies.”

Pawłuszko says that a major sea change in Polish military thinking happened in 2016. “Russia had annexed Crimea two years earlier and our politicians decided to throw their support behind our army,” he says. “Under Trump’s first presidency, the government aimed to please Washington by buying US weapons.” Yet, even then, there were signs of US fickleness. “The Americans weren’t willing to share military technology with us. Even PIS [the far-right, Trump-friendly Law and Justice party] realised that they had become a little arrogant,” he says.

So, Warsaw began to look farther afield to meet its growing materiel needs. Since 2022, the country has spent more than $20bn (€17bn) on South Korean arms, including hundreds of K2 tanks, light combat aircraft and heavy-artillery systems. For the Poles, this partnership has plenty of upsides. Quick turnaround times are coupled with the fact that South Korea has proved a willing partner in sharing technological know-how. Lengthy supply chains have been circumvented, with companies including WB Group and Hanwha building missile-production facilities in Poland.

Monocle sees some of the South Korean K2 tanks in action at a large military exercise in Poland’s northeast. Alongside troops from the US, Lithuania and the Czech Republic, Polish forces are simulating an attack on the Suwałki Gap – a land corridor wedged between Kaliningrad, a Russian exclave, and Belarus, a Kremlin ally – which has been called Nato’s Achilles heel. Military analysts believe that this picturesque region would be among the likeliest places to be struck, were Russia to attack the alliance. Venture close enough to the border with Kaliningrad and one will receive an unnerving SMS proclaiming, “Welcome to Russia.”

But during the exercise, codenamed Brave Boar 25, mobile-phone service is scant. Deep inside a thick forest, we hear jets roaring overhead. The exercise is intended to co-ordinate the full panoply of Nato aerial and land capabilities on Polish terrain. “The landscape that we’re training on here is completely new to us,” says one Czech captain who Monocle speaks to on condition of anonymity. We meet him in a mocked-up town surrounded by pines and thicket; while we talk, his men drill how to capture one of the larger buildings, creeping along roads and pathways modelled on a typical Polish settlement.

“At first, our tactics are a little different but after a few hours, we start to co-operate with more ease,” he says, explaining the importance of conducting exercises on unfamiliar terrain. “What we have seen during our time here is very impressive, especially the large numbers of soldiers and equipment. Poland’s command and control is on a high level.”

Leading today’s exercise is the Polish Armed Forces’ 16th Mechanised Division, which is based near the Suwałki Gap. Captain Karol Frankowski, a press officer, tells Monocle about the recent improvement in his country’s defensive capabilities. “When I came to the military in 2017, our division had seven units,” he says. “Today we have 11.” He reels off the names of some new pieces of equipment that the brigade has gained in the past few years, including K2 tanks and HIMARS rocket launchers.

Once a successful sports journalist, Frankowski joined up after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. “In 2014 a kind of information war started,” he says. “I realised that I needed to be a part of this structure to help Polish citizens.” In many ways, Frankowski’s career change mirrors the way that Poland has shaken itself out of its post-Cold War slumber in response to the growing Russian threat. Now, the press officer is tasked with attracting others like himself into fatigues, leading a government-backed initiative with the aim of recruiting 100,000 volunteers by 2027. In online videos, Frankowski attempts to appeal to Gen-Z Poles. “I explain that it is an adventure and that you get the chance to prove yourself,” he says. “People pay money to train in the gym – but here, you get paid to do physical exercise.”

Frankowski’s Instagram posts are part of a wider drive to make military training available outside the armed forces to hundreds of thousands of civilians. There is a recognition that Poland lags behind other front-line Nato countries, especially the Nordics, when it comes to civilian preparedness. “For many years, officials have been informing people that we are building our military power – that we’re buying tanks and helicopters, and creating new divisions,” says Pawłuszko. “But at the same time, people aren’t prepared for typical wartime threats such as bombs or rescue operations, let alone hybrid threats.”

Poland’s defence minister, Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, emphasises the importance of involving all members of society in preparing for war. “Our priorities are a strong army, a strong society and strength in the Nato alliance,” he tells Monocle. “I would like elements of defence education to become more widespread in schools and workplaces, and for the private sector to be more deeply involved in exercises and resilience planning.” This would involve a huge societal change. “The armed forces rank among the institutions with the highest levels of public trust,” says the minister. “ This shows a sense of shared responsibility for security. At the same time, we recognise that preparing society is a long-term process. That is why we are preparing voluntary universal training; we are running educational campaigns in schools and information campaigns in the media. It does not mean living in fear – it means confidence and calmness in the face of challenges.”

However, an aversion to joining up persists in many sectors of Polish society – a lingering effect of communist rule, which eroded trust in the state. This is exacerbated by acute political polarisation. Today only a third of Poles view the government positively. A lack of trust was evident after Russia’s drone incursion in September. According to a poll in the immediate aftermath, a third of Poles believed that Ukraine was to blame, rather than Russia. This wasn’t helped by mixed government messaging, which initially claimed that a Russian drone had struck a civilian house, when it could have been a Polish missile fired by an F-16.

After the incursion, which the prime minister, Donald Tusk, said had brought Poland closer to war than at any time since 1945, worried citizens took to social media. “What does a drone sound like?” asked one Facebook user. “How do I know if it’s flying close or far away from me?” Such questions are signs that the government’s crisis messaging isn’t getting through – as is the fact that many civilians affected by the air alert did not receive adequate instructions.

On Poland’s northern coast, the Aegis Ashore site continues to operate under US personnel and Captain Dwan is eager to stress that things, for now, remain business as usual. “Our mission has not changed,” he says. The base is equipped with SPY-1 radar, which offers a round-the-clock detection range of more than 300km. Still, many Polish politicians are privately wondering if capabilities such as this are of any use. In March, Washington informed its European allies that it would no longer participate in military exercises on the continent – though in a meeting with Poland’s president, Karol Nawrocki, in September, Trump said that he had not considered withdrawing US troops from the country.

The definitive year in Poland’s historical memory is 1939, when the country was divided between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany despite the rhetoric of Western allies. Today the situation is different. As the defence minister points out, European Nato allies, including Italy and the Netherlands, were involved in shooting down September’s drone incursion. “Poland is not alone,” he says. But Warsaw knows that if it is attacked, actions will be more important than words. The country is leading the way when it comes to European rearmament but it cannot afford to be complacent.