Welcome to Muscat, Oman’s quietly evolving capital

Driven by its Vision 2040 development program, the Gulf country is aiming to reinvent itself without losing sight of its distinct identity. We visit Muscat, as the ancient capital looks outward at the world.

Some pre-award videos are spoilers. As Muscat’s great and good wait to hear who has triumphed in the city’s inaugural architectural-design competition – the winner of which will receive a commission to construct a new landmark building – the opening promo comes with more than a hint of what’s coming next. It describes the Omani capital as a city that is “embracing the future” while “preserving tradition” and then as a forward-looking place that is nonetheless steeped in “ancient history”.

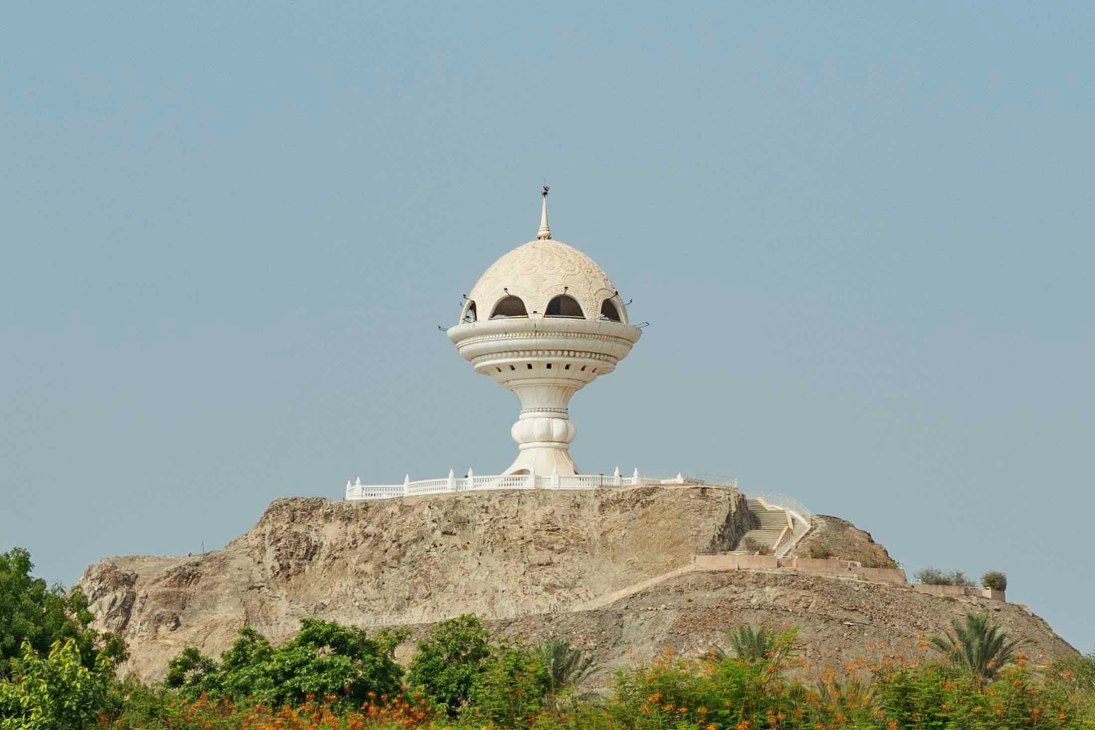

Despite the 42C heat outside the quadruple-glazed windows, Muscat isn’t your typical Gulf capital. If you blur your camera lens, a contemporary photo of this ancient port, situated between the Hajar mountains and the Gulf of Oman, could pass for a 19th-century daguerreotype. The city’s near-immutable face has been government-mandated, with strict building regulations introduced at the behest of former Omani leader Sultan Qaboos, enforcing a maximum height (40 metres) and a general design aesthetic (whitewashed, Arabic vernacular) since the 1970s. But change is afoot.

As part of the Vision 2040 economic plan, launched by the country’s new ruler, Sultan Haitham, the rules that have preserved Muscat in early-20th-century aspic are being relaxed, with the intention of using vast new building projects to attract foreign investment and increase tourism. Still, old regulations die hard and, as the aforementioned video makes clear, this particular revolution will not be of the Maoist variety.

So the lovely couple from Brussels-based practice Samyn and Partners probably won’t be winning for their eye-catching polychromatic design. After a seemly hush and the appearance of a minor royal, the winner is announced: Frankfurt-based KSP Engel, with a sandstone-hued, mid-rise office, hotel and entertainment complex that looks like, well, many of the other buildings in Muscat. “The best designs always come when you have the most restrictions,” Thomas Busse of the winning firm tells Monocle in a room ringed with gilded chairs. “That’s when you really have to be creative in order to solve different problems.”

The Muscat Municipality Design Competition, with its many caveats and stipulations, is a microcosm of Vision 2040 – an economic plan seeking to generate creative solutions to Oman’s looming problems. Like its Gulf neighbours, the country is aiming to attract more foreign direct investment (FDI) as a way of diversifying its economy away from fossil-fuel extraction, on which it has long been over-reliant. Some 70 per cent of Muscat’s revenue comes from oil or natural gas, which is scarcer and dwindling far more quickly than elsewhere in the region. In common with Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, the country is preparing for a future in which these resources are less accessible and valuable.

But as it has done for much of its modern history, Oman is looking to forge its own way forward – pursuing incremental, not drastic, change and doing things such as introducing the Gulf’s first income tax. Most Omanis meet comparisons between their country and other Gulf nations with a courteous rebuke.

“We leave it to others to figure out the difference,” says Muscat’s mayor, Ahmed Al Humaidi, the architecture competition’s sponsor. The affable president of the municipality is at the vanguard of what the country’s rulers hope will be an economic transformation similar to that experienced shortly after Qaboos ascended to the throne in 1970. When he came to power, the country’s average life expectancy was in the late forties, slavery was still legal and Oman was blighted by poverty, illiteracy and disease. When he died in 2020, having become the Arab world’s longest-serving leader, most Omanis could expect to live well into their seventies and literacy rates were close to 90 per cent.

Al Humaidi was plucked from the private sector to lead the only Omani municipality that is entirely self-funded – a city with a population that is expected to double from 1.5 million today to three million by 2040. Monocle meets him at the echoey, marmoreal municipality offices a few hours after the design award ceremony. A bowl of treacly Omani dates remains untouched until we avail ourselves, after which the mayor gratefully takes one and smiles.

In common with their Gulf brethren, Omani men usually wear an ankle-length white dishdasha or thobe but things diverge up top. On their heads, you’ll find an embroidered skullcap called a kummah, shrouded by an intricately wrapped, usually patterned turban or ghutrah. The least elaborate national dress in the Gulf region, the outfit’s modesty aptly reflects Oman’s regional role. As well as eschewing the development models of its oil-rich neighbours, Oman has been diplomatically neutral since the 1970s, pursuing a foreign policy that’s encapsulated in the mantra “Friend to all, enemy to no one”.

In a region riven by enmity, both ancient and modern, Muscat’s neutrality has enabled it to act as a broker between Iran and other Gulf states (as well as the US), and as a mediator between Qatar on one side and the UAE and Saudi Arabia on the other. It helped Qatar to circumvent a Saudi and Emirati-led blockade between 2017 and 2019, a move that surely had a bearing on Doha’s $1bn (€860m) bailout of Muscat in 2020 – money that helped Oman to avoid a severe economic crisis. Muscat’s increasing closeness to Doha has jeopardised its prized neutrality and now its drive to attract investment that might otherwise be bound for Dubai or Riyadh has put it into competition with its neighbours.

But there we are comparing the Gulf nations again. “We never look at it as a competition,” says the capital’s mayor. “We complement each other and have our own identity and position in the region.” Monocle’s guide from the municipality, Waleed Al Balushi, had earlier told us, “You will never hear a harsh word from an Omani,” and we are beginning to think that he might be right. The mayor’s mission for Muscat seems to be much the same as the government’s agenda for Oman as a whole: to transform it at the same time as keeping it largely unchanged. In this respect, he believes that the mild relaxation of building regulations – or what the country’s housing minister, Khalfan Al Shuaili, calls “improvements” – is actually an advantage.

“Having an architectural identity doesn’t stand as an obstacle to urban planning,” says the mayor. “When you have a distinctive identity, it makes it easier to innovate.” Indeed, the development unleashed by Vision 2040 involves far more than just tinkering with building regulations. Oman is presently engaged in a number of what might be called “giga projects” if they were happening elsewhere. The most ambitious of these is a new “futuristic, modern and sustainable city”, Sultan Haitham City, built on 14.8 million sq m of undeveloped land in Al Seeb, a Muscat suburb. When it is completed, it will contain enough homes for as many as 100,000 people. Then there’s the Al Khuwair Downtown and Waterfront development, a Zaha Hadid Architects-designed 3.3 million sq m neighbourhood that will include new homes for about 65,000 people and even – at least, according to the renderings – Muscat’s first large skyscraper.

Both of these projects and several others were conceived by the country’s powerful Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, whose headquarters Monocle visits on another searingly hot afternoon. At the age of 18, every Omani is given their own plot of land and the country has one of the world’s highest homeownership rates (89 per cent).

In Muscat, where many have built palatial, US-style villas on these plots, urban sprawl has put huge strain on the city’s infrastructure and resource management. As well as seeking to build enough homes for a population of which more than 40 per cent of people are under the age of 24, the ministry has tinkered with land distribution laws. “Now we provide our citizens with a variety of options,” says Al Shuaili, the housing minister. “They can still get a plot but there are limitations on how that can be used and when it should be used.” His aim is to “improve density” by creating “lower houses” and “less urban sprawl” but also to change a culture that views detached compounds as the ideal of city living.

This mission is already bearing fruit. The minister says that 50 per cent of Muscatis currently live in apartments and many of the new settlements planned as part of Vision 2040 are made up of multiple-occupancy units. “We don’t aim to reduce the size [of dwellings] but to keep them closer so that people can walk, work or study within their new communities,” he says. Again, much of the ministry’s success will be measured against that of Oman’s neighbours. Over several decades other cities in the region have suffered property busts, as well as the speculative construction of neighbourhoods that then remained empty due to a lack of interest. “As a ministry, we keep a very close watch on supply and demand,” says Al Shuaili.

As well as satisfying the country’s native-born housing needs, the building boom is intended to entice foreigners to invest in Omani property. While removing minimum capital requirements and allowing 100 per cent foreign ownership for Oman-based companies in many sectors, the country has also relaxed rules on non-citizens owning freeholds and the properties in all of the new Vision 2040 developments will be available for purchase from overseas. The property sector has shown strong growth in recent years (prices increased by 7.3 per cent year on year in the first quarter of 2025) and the minister hopes that the calibre of new developments, coupled with relatively low prices, especially compared with other Gulf states, will lead to more foreign purchases and strong returns for those Omanis who choose to buy rather than build their own homes.

Monocle is presented with several kilogrammes of promotional literature trumpeting dozens of new cities but the minister stresses the measured nature of Oman’s development drive. “When you look at these projects, you have to put them in the context of the next 15 years,” he says. “None of these cities will spring up all of a sudden. It takes time. And whether we begin building in 10 years or 20, that’s OK for us, as long as it’s sustainable growth and that nothing will be built unless there is demand for it.”

Though my Omani interlocutors refuse, for both diplomatic and decorous reasons, to see the regional competition for FDI as a zero-sum game, it is difficult not to view many of their plans and much of their rhetoric as an attempt to avoid the pitfalls that other Gulf states’ development drives have encountered in the past. In this respect, Sultan Qaboos left an architectural legacy that has put the country in a strong position. “I often compare him to Martha Stewart,” says Jim Krane, Middle East expert and author of City of Gold: Dubai and the Dream of Capitalism. “He just had a wonderful kind of quirky aesthetic and design sense. And he imposed it on the country for 50 years.”

Oman’s aesthetic uniformity, coupled with its unparalleled and largely unseen natural beauty, is a huge boon for its tourism industry. Visitor numbers hit a record 5.3 million in 2024, a 3.2 per cent year-on-year increase. Both are consequences of the deliberately hesitant approach to FDI and large-scale development that pervaded in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. “Oman has been quite successful in being understated and following a very different approach to what the UAE and Qatar are doing,” says Mohammad Najmuz Zafar, the deputy editor of Muscat Daily, a national newspaper based in the Omani capital.

Then, of course, there’s the impact on the built environment. “It hasn’t gone through the same huge economic booms that have really shaped Dubai, Doha and Riyadh,” says Krane. “Those booms create these big, physical legacies, which is why you see so much brutalist architecture around the Gulf, because of the 1970s oil boom.” In her 1955 book Sultan in Oman, British travel writer Jan Morris wrote with great prescience, “Such was the character of Muscat, perched in the place where the Omani mountains reached the sea, that quaint old traditions could not only be honoured; they could also very easily be institutionalised.” As the country aims for its second great leap forward in a generation, it will be hoping to retain a large deal of that quaintness.

The Switzerland of the Middle East

In the seventh century the Omanis became one of the first peoples to convert en masse to Islam, leading the Prophet Muhammad to suggest in a prayer that they would never have any external enemies, only ones from within. The idea of diplomatic neutrality, present to various degrees throughout the country’s history, reached its apotheosis during the rule of Sultan Qaboos, 13 centuries later. Before Qaboos’s rule, Muscat had been largely content to stay out of world and even regional affairs, effectively ceding much of its foreign policy to the British Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

But in 1970, its new young ruler set out to take advantage of his country’s key geographical position at the mouth of the Arabian Gulf, a part of the world integral to global energy supplies. Under Qaboos, Oman joined the Arab League and the UN and became a founding member of the Gulf Co-operation Council in 1981. Despite its close relations with its Gulf neighbours, as well as the West, Muscat has also maintained friendly diplomatic ties with Iran, acting as a channel between the country and Israel and the US during this summer’s outbreak of conflict. Oman hosted the talks that led to the Iran nuclear deal in 2014 and has been mooted as the location for future negotiations involving Tehran.

Qaboos also sought to bring the two parties in the Israel-Palestine conflict to the negotiating table. Benjamin Netanyahu visited Oman in 2018 and the country’s foreign minister called for the recognition of Israel, a rare statement from an Arab state at the time. Still, the nation didn’t participate in the Abraham Accords that saw the UAE and Bahrain formalise diplomatic relations with Israel in 2020. And under Qaboos’s successor, Sultan Haitham, relations have once again deteriorated with Tel Aviv, owing in large part to the war in Gaza. Oman’s prized neutrality has also been threatened by its growing closeness to Qatar, a neighbour that has recently fallen out with two others (Saudi Arabia and the UAE). As the Middle East once again roils in conflict, Muscat’s famed diplomatic nous faces one of its most serious tests.

Oman’s natural beauty

A camel slowly padding through a lush forest might sound like an AI-generated image but in Oman such fantastical scenes are an annual occurrence. Between the months of June and September, the Omani city of Salalah and the surrounding Dhofar region – at the southernmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula – see monsoon rainfall and a consequent explosion of wildlife. The Salalah Khareef (Arabic for autumn) is essentially an extension of northern India’s monsoon season into Oman, a meteorological phenomenon that has long drawn visitors from the region who are seeking respite from the punishing mid-summer heat. As the Omani government attempts to draw more tourists to the country, especially from Europe and North America, it is using its natural beauty and diverse wildlife as an enticement.

“Oman’s physical beauty is pretty much unparalleled [in the Gulf],” says Jim Krane, a regional expert. “The only place that comes close is Yemen, or maybe the very far southwest corner of Saudi Arabia. And you can see that the government is trying to lean on that.”

In 2024, visitors to Salalah and the Dhofar region exceeded one million for the first time ever, representing a nine per cent year-on-year increase – and this is counting only arrivals during the Khareef. The government has invested more than $200m (€172m) in improving tourism infrastructure around Salalah, alongside a pledge to build 40 new hotels across the country by the end of 2025.

As well as a hospitality drive, Muscat is keen to expand leisure and recreational attractions. Rising up from the desert on the outskirts of the capital is a development that will become one of the world’s largest botanic gardens when it opens in a few months’ time. The Oman Botanic Garden is both a tourist attraction and research centre, and perhaps the most straightforward example of the government’s attempt to harness its natural attributes for soft-power purposes. Its 420-hectare site will contain all 1,407 of the recorded plant species found in the country. Monocle visits on a scorching July morning and is amazed to enter its two massive greenhouses and find them cooled to a frigid 19C, with thickets of lavender, rosemary and olive groves, and songbirds flitting between trees.