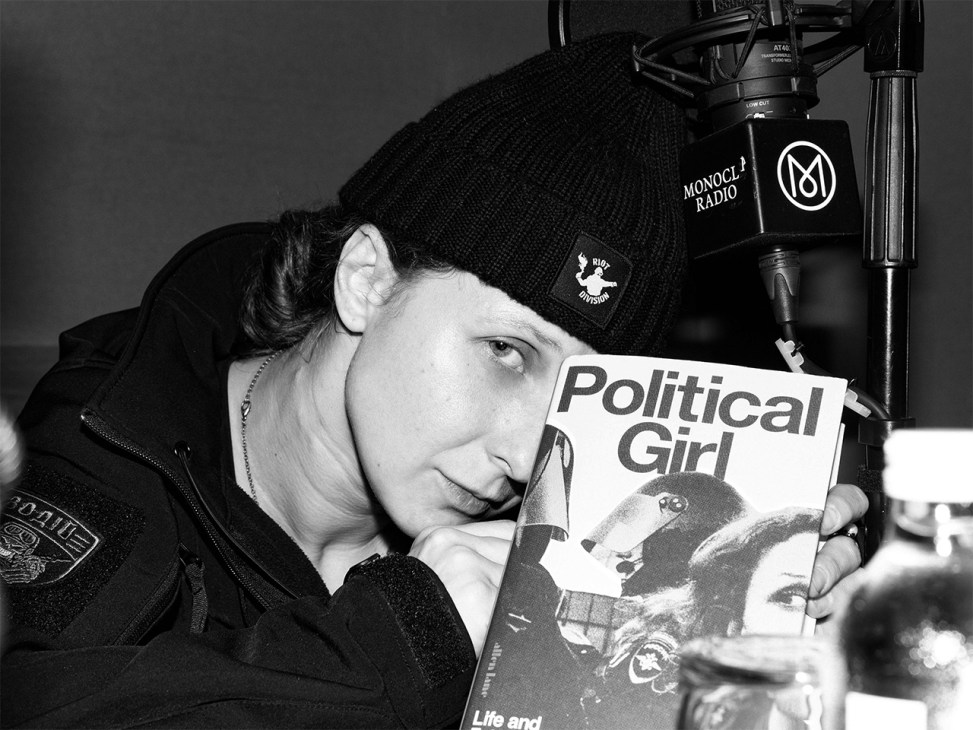

‘Anyone can be killed at any moment’: How Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina remains firm in the face of persecution

The Russian political activist’s second book outlines her experience in a penal colony, the art of protest under authoritarian rule and amplifying the voices of Russia’s unheard political prisoners.

Maria Alyokhina is a Russian political activist known for her work as a member of Pussy Riot, the feminist protest group. The collective was thrust into the global spotlight in 2012 after an audacious performance inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

Alyokhina has just released Political Girl: Life and Fate in Russia, which details intimate accounts of her work as an activist between 2014 to 2022. In the book, she recounts her near two-year-long imprisonment in a penal colony and reflects on the Kremlin’s suppression of LGBTQ+ rights in Russia. Here, Monocle’s Georgina Godwin speaks to Aloykhina about the harsh realities of living under Vladimir Putin’s regime, the activist’s support for those still imprisoned and her hopes for the future of her country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to it in full by tuning in to Meet The Writers on Monocle Radio.

When did you realise that art could be used as a weapon?

I was asked to film an activist group rehearsing an action they were planning. At first, I didn’t know what ‘action’ was but basically, it is protest in the form of art. They were preparing an action inside a courtroom where the state was prosecuting two art curators for their exhibition about religion. That was when I first realised that the state can prosecute people for putting on exhibitions. The [curators] didn’t receive a prison term but they were criminally prosecuted.

How did the group Pussy Riot come together? And what did you think about the consequences of your work?

The time between the end of 2011 and the beginning of 2012 was one of hope. There was a large movement in Russia protesting Putin’s third presidency and we were part of that. There were zero artists or activists in prison at that time. My goal was to show through our actions how Putin was shutting down freedoms. We decided to protest the church promoting Putin and I was surprised when they opened a criminal case. When I was taken by the police, I left my apartment [after] telling my son that I would come back tomorrow. I came back two years later.

The book starts at the point at which you’re leaving the penal colony. What was it like inside?

In Russia, we have a post-Gulag system during pre-trial and trial investigations where you are held in a jail cell. After the sentencing they transport you to a penal colony, which is a number of barracks where 100 women sleep together in a room with just two or three toilets, no hot water, no normal food and a [single] fridge. Another part of the colony is a working zone – a factory where prisoners sew uniforms for the police and Russian army.

Russia today has thousands of political prisoners, many of them unknown. What do you think that readers [of your book] need to understand about them?

Now, with the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine], anyone can be killed and people go to prison for 20, 25, 29 years for just being against this fucking war that Putin started.

It’s clear now, after Putin killed [Russian opposition leader] Alexei Navalny, that anyone can be killed at any moment. Inside the country, there is a network of concentration camps. They put people from the occupied territories into these buildings and hold them there incommunicado, without status. They are not officially prosecuted but this is happening right now to 20,000, 30,000 people. Lawyers I know work with these [prisoners] and they say that they are being tortured. Sometimes [the government] opens official criminal cases [against these people] and transport them to prisons. There, they might speak to other prisoners about what they have been through. That’s how information about these places has become known.

Further reading?

– Russian opposition activist Vladimir Kara-Murza on surviving Putin’s gulag – and the moment when he thought he would be executed

– Ukraine’s women have the skills needed on the battlefield

– Are Poland’s efforts to bolster its defences enough to deter Russia?