The effort to rebuild Syria: Life after the fall of the Assad regime

Following the fall of Bashar al-Assad, the US has decided to lift sanctions on Syria. As Donald Trump meets the nation’s new leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, we consider how it is rebuilding its cities.

Updated 14 May: The US has taken the surprise decision to lift its long-standing sanctions on Syria. As Donald Trump meets with the nation’s new leader, reformed rebel Ahmed al-Sharaa, in Damascus, we’re revisiting this story from Monocle’s April issue about the opportunities and potential pitfalls that Syrians face as their country reopens to the world. With the West now set to re-engage with Syria after a devastating civil war levelled vast swathes of its cities, our Istanbul correspondent, Hannah Lucinda Smith, meets the people looking to rebuild the nation, as well as the contractors hoping to make a tidy profit along the way.

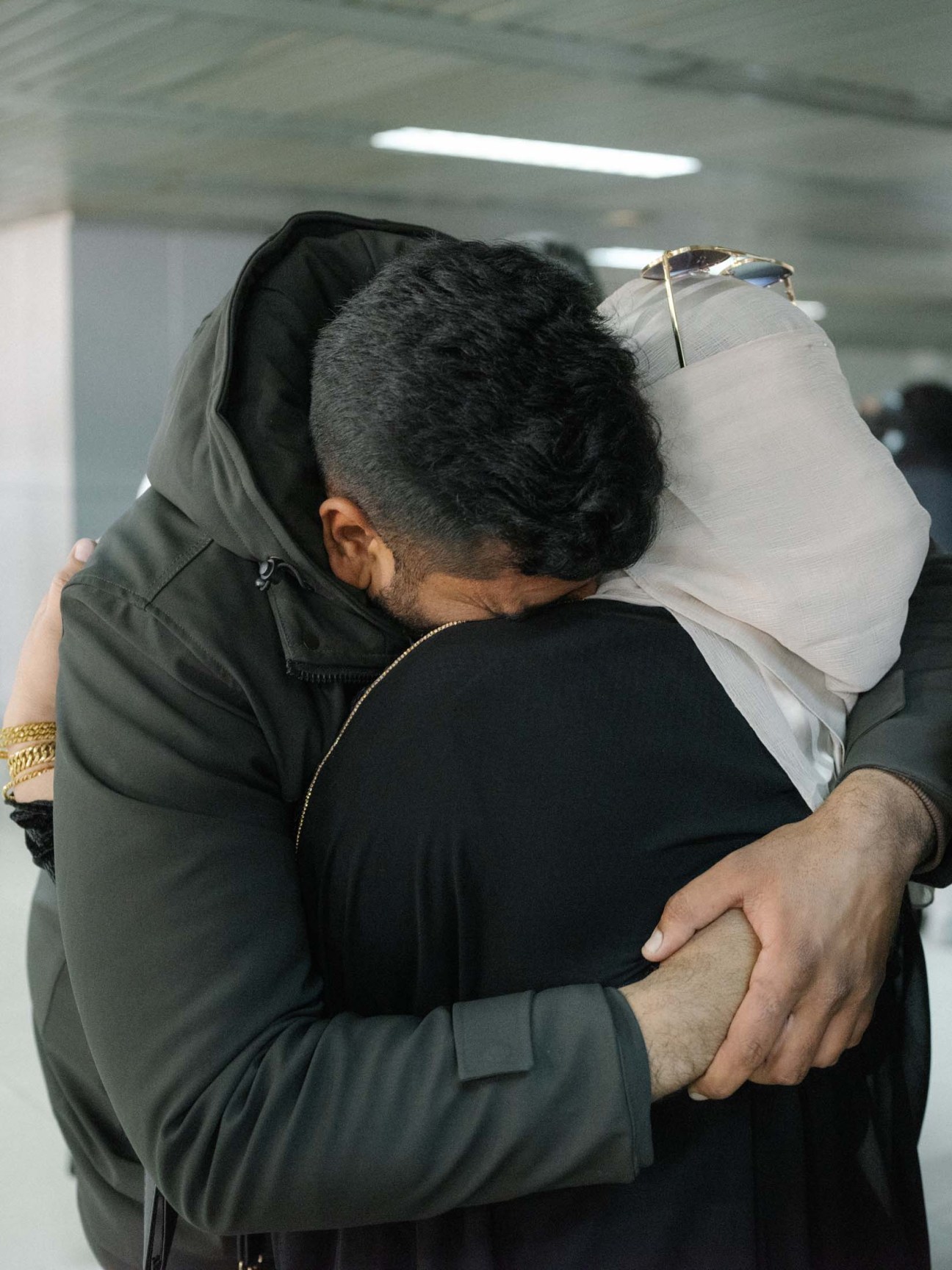

There’s a burst of applause and a chorus of an Arabic song as the passengers of Turkish Airlines flight 846 touch down at Damascus International Airport (DAM). An old man pauses on the steps down from the aircraft. “Congratulations to us all, by God!” he says, holding his bag aloft. “Assad is gone and we are back.” Inside the rundown arrivals hall, a crowd jostles for its first view of relatives returning after years of exile. Despite the many traumas that Syria has lived through, the mood is exuberant. In the car park, a band plays celebratory music while a white-cloaked dervish whirls amid a dancing, flag-waving throng of people. Everyone exiting the airport walks over a picture of the face of Bashar al-Assad, the erstwhile president who fled from this same airport on 8 December.

Syria is a country transformed overnight, from an insular, heavily sanctioned and brutal dictatorship into a chaotic but cautiously optimistic free state. Its new rulers, technocrat Islamists who for years ran a quasi-state in the rebel-held north of the country, have promised to respect the nation’s ethnic and religious diversity. Transitional president Ahmed al-Sharaa’s first aim is to lift the crushing sanctions that were imposed on Assad’s regime, which will allow Syria to start trading internationally and receive foreign aid and investment. So far the US has granted limited humanitarian exemptions but most of its commercial embargoes remain in place. The EU suspended its sanctions on energy, transport and banks on 24 February.

Turkey, a close ally of the new Syrian administration after consistently supporting its fight against Assad, is ready to do business. Thrice-weekly flights from Istanbul that began on 23 January are booked months ahead, with many Syrians returning home for the first time. Turkey’s national carrier was the second international airline to resume its route to Damascus after Qatar Airways.

Ghosts of the almost 14-year civil war greet you even before you disembark at dam, in the shape of dozens of rotting commercial jets scattered around the bumpy runway. Sanctions mean that Syrian Air, the national carrier, and Cham Wings, a private operator, have been unable to fly to most places in the past decade; the few planes that are still operational have been repainted with the new Syrian flag. Turkey’s ministry of transport and infrastructure is soon to begin helping to overhaul the airport.

What the future holds is unclear but one thing is certain: Syria must be rebuilt. More than half the population is displaced, more than 130,000 buildings are destroyed and economic output has halved. Who the stakeholders in the reconstruction are and what they prioritise will shape not only the built environment but also the success – or failure – of this shattered nation. Key to it all is money: USAID is frozen, humanitarian organisations are holding back and Western companies are hesitant to enter the Syrian market. That leaves the door wide open for the country’s closest geopolitical allies – Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and, above all, Turkey – to seize the opportunity.

“I got my first calls from Turkish companies days after the regime fell,” says Alaa al-Hilal, the founder of BuildEx, an annual international construction fair that has been held in Damascus since 1996 and was once one of the biggest events of its type in the Middle East. Turkish builders had a large foothold in Syria’s pre-war market. Hilal holds up a thick, dog-eared guide from BuildEx 2010, which bristles with Turkish contacts. After 2011, however, everything stalled. “We work as if time stopped on the day the war started,” says Hilal. “We don’t have the latest tools, construction materials or techniques.”

Syria stands on the brink of becoming the world’s biggest building site and investors are lining up. Whole communities must be remade from the ground up, with entire towns and city suburbs reduced to urban scars devoid of infrastructure, commerce and people. While there are still some successful Syrian manufacturers and constructors left in more functioning parts of the country, many businesses moved their operations to Jordan, Egypt or Turkey to keep trading when sanctions were imposed.

To rebuild the country, help from beyond its borders is needed. In BuildEx’s office, phones ring constantly with foreign firms looking to book exhibition spaces at the forthcoming event in May. The derelict halls and vip lounges of the Damascus Fairgrounds, a faded relic built in 2003 to host the city’s international fair. During the Assad years, the event was dominated by companies from the former president’s closest allies: Iran, Russia and China. But this year the biggest contingent is from Turkey.

In June, a Turkish exhibition company will run a separate event in Damascus hosting companies that can build sports facilities and amusement parks, as well as housing and infrastructure. It’s a reflection of the scale of the rebuild ahead. Fabo, an Izmir-based company that sells and services concrete-crushing equipment, has signed up. “It is our best opportunity in 20 years,” says Omur Gulec, one of the firm’s directors. Syria is currently under a sea of rubble but Fabo’s equipment can scoop it up, compress it and turn it into concrete. “We are neighbours; our cultures are close and we helped Syrians during the war. It’s a big chance for everybody.”

Over at the reopened Turkish embassy in Damascus, ambassador Burhan Koroglu is dusting off his desk and settling in. Trade attachés have been appointed and, back in Turkey, business federations are holding events to discuss opportunities in Syria. There is a boom moment waiting to ignite but it hinges on how fast crippling sanctions can be lifted and some normality restored.

Syria currently has the most open trade policy in the world simply because it doesn’t have one. Borders that were almost entirely closed for import and export under Assad have been opened and products that were banned are flowing into souks. After Ankara and Damascus cut diplomatic ties in 2011, any trader caught selling Turkish goods was slapped with a heavy fine and risked prison. A few foreign consumer products, such as electronics and solar panels, were imported from China but otherwise almost everything was Syrian-made.

At his shop in the historic Souk al-Hamidiyeh, Abdulrahman al-Horani is selling Turkish dried apricots and cevizli sucuk, a walnut-filled sweet found in every confectioner’s in Istanbul. His family has run the business since 1930, and Horani, aged 17, is well-versed in Syria’s Byzantine import rules. But within two weeks of Assad’s fall, he was selling goods brought over the border by Syrians living in Turkey. “Everything that is sweet tastes better from there,” he says. “Turkish goods are the norm now because there are no duties.”

View from an architect

Ziwar al-Nouri is an architect and researcher who trained under Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid. He returned to his native Syria in 2018 to set up the Reparametrize Lab at Damascus University’s architecture faculty. The urbanism lab explores visionary solutions to Syria’s reconstruction challenge.

What is the biggest challenge facing Syria’s architects?

There are a lot of failed examples of postwar reconstruction. In Beirut, for example, they only considered the economy when they rebuilt after the civil war. Now the city centre is empty. Diving straight into reconstruction is a problem.

What is an example of successful urbanism in Syria?

The Old City of Damascus is still a successful prototype because it was built by the people who lived there. It is a complete system, with spaces for manufacturing, trade and religion. It was the original 15-minute city, a concept that has become fashionable once again.

How should the war be memorialised through architecture?

We need to start by engaging the community. People have memories attached to destroyed places, so we propose regenerating and reusing buildings wherever we can. We need sponsors and international aid but we also hope that working with Damascenes will be a top priority.

Who is Syria’s new government?

The new regime in Damascus is the first government of any country in the world to have once been affiliated with Al-Qaeda. But Ahmed al-Sharaa, the leader of rebel militant group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, rebranded and reformed in the years before he swept into Damascus as interim president. At Syria’s first ever pluralist conference in February, he promised to restore justice and rights and to protect minorities. Al-Sharaa has also held meetings with European diplomats and Arab leaders. His closest relations are with Qatar and Turkey. Ankara’s foreign minister, Hakan Fidan, drank coffee with Sharaa on Mount Qasioun just two weeks after Assad’s fall. Sharaa’s biggest domestic challenges are remaining Assad loyalists, who have launched large attacks on his forces, and preventing revenge attacks in his fractured country.

After years of privation, Damascenes are desperate to open their eyes, country and wallets to the world. Though the worst of the fighting around Damascus ended by 2018, the US imposed heavy commercial sanctions on Syria a year later in response to evidence of war crimes leaked by Caesar, a regime defector who fled to the West. The embargoes brought Damascus to its knees. For many years, Syrians have been locked out of the international banking system. A convoluted process of sending payments through Dubai, Beirut, Cairo and Ankara has sprung up, allowing foreign traders to do business in Syria.

Nevertheless, ministries are starting to get back to work. The sudden flood of foreign products into the Syrian market is a sweetener for a long-suffering people. Over the long term, however, it will leave the country with a negative trade balance. Syrian manufacturers have already suffered the loss of international markets, while domestic consumption has crashed.

Before the war, family-owned aluminium manufacturer Madar was Syria’s second-largest private-sector exporter, with an annual turnover of $200m (€193m). Hassan Daaboul, Madar’s general manager, had to leave the country in 2012 but kept the factory in Syria open while establishing partnerships in Jordan and Egypt to supply international customers. Now he wants to bring the work back to Syria. “Our plants and our people are ready,” says Daaboul. “But does the Syrian government have a strategy for the economy? The market is filled with Turkish products, from metal to chocolate. But if we are just a market for Turkey, the economy will be a disaster. Syria was a manufacturing hub before. If we don’t grow our own industry, we can’t provide jobs.”

Monocle meets Daaboul in a five-star hotel in the city centre, many of which were taken over by the new government after the regime fell. His relative, Humam, takes us on a drive to the devastated suburb of Darayya, where their family once lived. Assad’s army gave Humam just five minutes to leave his home in 2011. When he returned in 2019, the neighbourhood was devastated and the Daabouls’ building was a shell. They have since reconstructed it themselves, wrapping new stone and breeze-block around structural columns that were, miraculously, still standing. Life is slowly returning to the streets and a restaurant of some local renown has reopened on the refurbished ground floor of a destroyed block.

Now 25, fluent in English and a civil engineer by training, Humam is typical of Damascus’s war generation. “I want to change everything,” he says, surveying the ruin of his old neighbourhood. “This needs someone to study a regional plan, look at sustainability. There should be green places. This area has water; it should be blue and green.”

Damascus’s Old City, a Unesco World Heritage Site, is mercifully intact. Much of the destruction happened in newer suburbs built on old farmland. These areas included unplanned settlements and large Soviet-style housing projects from the 1980s – relics from the era when Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, began cosying up to Moscow. Damascus’s modern architecture is rundown, with much of it carrying connotations of the old regime. Some buildings, such as prisons, intelligence branches and the modernist presidential palace designed by Kenzo Tange that was completed in 1990, are overt reminders of Assad’s despotism. Yet the question of whether to destroy, preserve or renew these structures is not straightforward.

“It is important to understand where we are now and how we can develop in the future,” says Mirma al-Wareh, the co-founder of the Archive of Modern Architecture, a project set up in 2020 that aims to document Syria’s 20th-century architecture. “Reconstruction is

complex. It needs to consider the context of each area.”

Damascus, one of the world’s oldest inhabited cities, will survive. Some 40 per cent of Syrians are under 15 and returning emigrés are bringing new connections back to their homeland. Syrians entrepreneurial enough to have built businesses during the war are now poised to reap the rewards. Tourism will be important too. Rami Nawaya founded travel agency Syrian Guides in 2019. He has future plans to launch a vineyard tour. When he passes destroyed areas as he takes groups between Syria’s famous sites, he is now able to fully explain what happened there.“There is much to be done,” he says. “But the moment we are fully open, Syria will boom.”