How Montpellier’s mayor is leading Europe’s mobility transformation

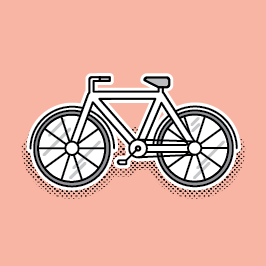

Montpellier’s visionary leader is reshaping his city with bold mobility and pedestrianisation schemes. But do his ambitions extend beyond the city’s limits?

“I have a carnal relationship with Montpellier,” says Michaël Delafosse, the French city’s 48-year-old mayor, in between sips of his morning coffee.This kind of statement would raise eyebrows coming from an ordinary local politician. But Delafosse, wearing a slim-fit suit and sporting a closely cropped beard, can somehow get away with it. Perhaps it’s because his style is backed up by a track record of undeniable substance.

Montpellier is that rare thing in France, as well as the rest of Europe: a provincial city with a rising population and a flourishing economy. Nestled in the southern administrative region of Occitanie, about 10km inland from the Mediterranean Sea, it has been France’s fastest-growing city since 2000 and is now its seventh largest. The Montpellier Business & Innovation Centre (BIC), the city’s incubator, has fostered a bustling start-up scene that has attracted the likes of game publisher Ubisoft and the creative division of state broadcaster France Télévisions, both of which have relocated here.

Montpellier has also positioned itself as a hothouse of avant-garde urbanism. It became one of the first cities in Europe to reintroduce trams in 2000, having abandoned them in 1949; in December 2023 it made public transport free for all residents. The latter was among Delafosse’s key campaign pledges during the 2020 municipal election, alongside a commitment to expand the city’s cycle-lane network (which now extends to about 235km) and turn central Montpellier into the continent’s largest pedestrianised urban area.

Despite his success on what could be called the radical side of urban politics, Delafosse – a history and geography teacher by trade and a longstanding member of France’s Parti Socialiste – isn’t a straightforward left-winger. He has taken strong stances on issues such as security, increasing police funding and CCTV coverage, tough-on-crime positions that have resulted in death threats from local drug traffickers. At the same time, he has pursued environmental and social-housing policies that have drawn criticism from opponents on the right. These moves, alongside his vocal rejection of some of Emmanuel Macron’s national policies, have seen him buck the trend of a Parti Socialiste that has appeared caught in a perpetual downwards spiral.

Delafosse has been marked out as a rising star in the party and is being talked about as a future presidential candidate. Though the mayor’s approval ratings hover at the 65 per cent mark – a rare feat in polarised France – Delafosse has his critics, many of whom argue that he has always had an eye on the Élysée Palace. In a 2022 profile in national daily Libération, an acquaintance described him as “hard to pin down”. He has refused to say whether or not he will run for a second term in March 2026, insisting that he has already achieved “two mayoral mandates in the space of one” – a claim that has led to allegations of arrogance in some local newspapers.

Before he commits either way, Delafosse wants to show Monocle around his hometown. After a morning caffeine hit, he hops on his electric bike. We are on the outskirts of the city in Halle Tropisme, a former military warehouse that was built in 1913 and now houses 10,000 sq m of space for artists’ studios, exhibitions and events. Nextdoor is an old military barracks that is being repurposed as part of an eco-district with 2,500 new homes, a third of which will be allocated to social housing.

Together, the two former brownfield sites will form the heart of the new Cité Créative neighbourhood, which is slated for completion by 2027. From December this year, a 16km tram line will link it to the rest of Montpellier. The Cité Créative typifies Delafosse’s approach to urban renewal: developing brown-field sites rather than breaking new ground, while using buses, trams and trains as the engines of change. Not having to pay to ride into town should increase the attractiveness of the neighbourhood to prospective residents.

Perhaps more crucial to the mayor’s plans, though, is a pledge not to raise taxes on ordinary citizens to fund the city’s free-transport scheme. Its annual cost of approximately €40m is largely being borne through a mobility tax imposed on companies with at least 11 employees (which benefit from a more mobile workforce, according to Delafosse), as well as central-government funding. The mayor also points out that revenue is still rolling in from out-of-towners, particularly tourists, and that there have been savings from paring back the fare-collection infrastructure.

The city’s residents have mostly welcomed the scheme. Several informal surveys by local media suggest an overwhelmingly positive response from users, especially students, who make up about 17 per cent of Montpellier’s population. “It’s amazing,” teacher Fiona Joyce tells Monocle. “Everyone I know thinks that it is too.”

When he announced the plan, Delafosse said that he hoped to see an increase of about 20 per cent in the number of passengers on the city’s transport network by 2026. After just 12 months, the network reported a 33 per cent rise. Transport unions, however, disagree that this is unequivocally positive. Their members have decried a “degradation” of the overall service as a result of overuse, as well as the additional burden on drivers. Delafosse bats away such criticisms. “In Paris, the service is expensive and it is still overburdened,” he says. “In any case, cities that have implemented free transport don’t turn back.”

Laisné and Manal Rachdi in 2019

As in other places across the globe, Delafosse’s plan to pedestrianise the city centre by banishing most private cars has run into fierce opposition from shopkeepers who fear a decline in footfall. Newspapers in Montpellier have devoted countless column inches to listing noise complaints and roads closed due to construction. Though Delafosse’s enthusiasm is hard to resist, the frequent sight of cafés, épiceries and boulangeries standing empty behind metal sheets and pedestrian-diversion signs on a sunny July morning isn’t particularly reassuring.

“I was here when the first tramline was being built and we were complaining then too – but afterwards we all thought, ‘Wow, this has changed our lives,’” says Vincent Cavaroc, the director of Halle Tropisme. “We were also moaning that we would no longer be able to drive our cars into the city centre. But today everyone is happy to have one of the largest pedestrian centres in Europe. All of this has required a lot of audacity on the mayor’s part: after all, the best way to get re-elected is usually not to touch motorists. But he has carried out very important work.”

As recently as 2022, 40 per cent of journeys under 2km in Montpellier were made by car. Cavaroc echoes a common sentiment when it comes to the pedestrianisation of city centres: before it happens, some people vociferously object but many erstwhile opponents are later won over by a transformed urban space. To force through such radical change, politicians need charisma and conviction, both of which Delafosse has in abundance. The debate, however, is often divisive.

“If we want ecology to be a common concern, we must include everyone,” says the mayor as we stroll down the Esplanade, Montpellier’s historic central boulevard that makes up the main artery of its new pedestrianised zone. “That’s why free public transport is such a powerful lever. It reconciles respect for the planet with the social dimension of having accessibility for all.” A family of four, he explains, can make savings of €1,470 per year thanks to the scheme.

Under a canopy of towering elm trees that flank the main walkway, Delafosse pauses for a moment to watch a couple of children playing in water jets as their mother watches on from a nearby bench. Behind him, a few spindly specimens of the 50,000 trees that he has pledged to plant by 2026 sway in the breeze. “Show me where the children are and I will tell you what kind of city you are in,” he says. “A city that thinks of its children’s place in it is one that thinks of the future.”

As to what he believes his own future holds, Delafosse keeps us guessing, saying only that he will announce whether he will run again after a period of “reflection” with his family. If Monocle had to guess, we would wager that Montpellier’s mayor will soon be hopping on the TGV to the Gare de Lyon. He has achieved a lot in just five years and exemplifies a certain type of ambitious 21st-century politician whose views on urbanism align with a populace that’s open to reimagining the urban space. But for now, he’s back on his electric bike, riding off into the afternoon.

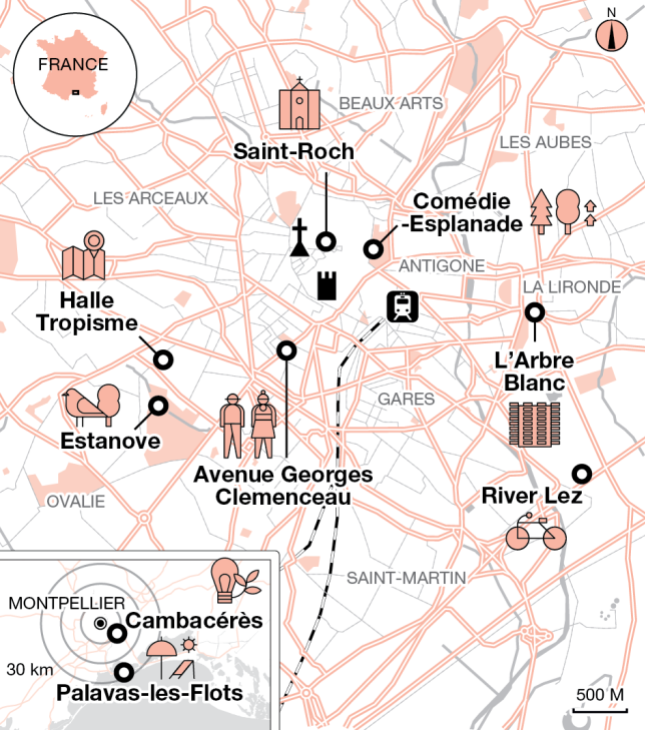

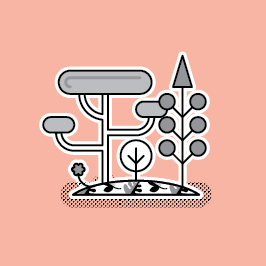

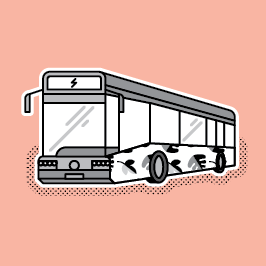

Montpellier mobility in numbers

Green spaces

About 500 new trees, 2,000 shrubs and 700 bushes have been planted in Parc Georges Charpak, creating wildlife corridors and boosting urban biodiversity. In Parc Marianne, wildflower grasslands now cover 1.5 hectares.

Buses

The first line of a new Bustram network opened in May. Manufacturer MAN Truck & Bus France, which has supplied 70 electric buses, commissioned illustrator Alain Le Quernec to create a design for each of the five planned lines.

Cycling

Under Delafosse’s administration, more than 150km of new cycle paths have been integrated into the city’s network. A 384-metre underground cycling tunnel will also connect the Comédie and Antigone areas of the city.

No cars

The city’s main thoroughfare, Avenue Georges Clemenceau, was fully pedestrianised in 2022, removing the some 11,000 vehicles that drove along it daily. A low-emission zone has also been implemented across most of the city.

Trams

Montpellier’s enviable tram network continues to expand. Line 1 has recently been extended to the city’s Sud de France TGV station, while a new station has been added to Line 3 to provide better service.