Monocle’s Quality of Life Survey 2025: The 10 most liveable cities in the world

We present our 18th annual Quality of Life survey: a ranking of the world’s municipalities according to what they do better than anyone else, be it health, safety, housing or nightlife.

1.

Paris

Best all-rounder

Our city of the year. The French capital’s strengths are multitude.

“I can honestly say that there’s no city in the world in which I would rather live,” says Charles-Antoine Depardon, an architect and advisor on urban development to Paris’s city council, as he strolls through the Tuileries on his way to work at the Hôtel de Ville. “It is an extraordinary cocktail.”

Depardon might be biased but on a spring morning, as the French capital’s avenues resound to the click-clack of hard leather shoes on spruce concrete, it’s hard to argue with him. Last year’s Olympics provided Paris with the platform to showcase its chic 21st-century self. The city delivered a rousing performance that also served as a fitting coda to a decade of revival under mayor Anne Hidalgo, whose ambitious (and, sometimes, controversial) urbanism interventions have made it cleaner, greener and safer, while maintaining and protecting the things that give it its inimitable charm. Paris in the 21st century looks a lot like it did in the 20th century but that’s a large part of the appeal. And today it is also a more international, outward-looking city than it has ever been.

One of the most notable changes has been the huge expansion of the cycle-lane network, which led to bike usage doubling between 2023 and 2024, and the overhaul of the once-creaking Métro, the backbone of which is the speedy new Line 14. This takes passengers from Paris-Orly Airport in the south to the new Saint-Denis Pleyel station in the north in just 40 minutes.

Meanwhile, in its bid to become the greenest major city in Europe, Paris has embarked on a gargantuan effort to plant 170,000 trees by 2026. At the time of writing, more than 120,000 are in the ground, many of which will be used to cultivate new urban forests, such as the one inaugurated in June 2024 at the Place de Catalogne. “Paris is a far more pleasant place to live today,” says Lindsey Tramuta, a journalist who hosts a podcast called The New Paris and has called the 11th arrondissement home for 19 years. “It was always a beautiful city to walk in but that’s even more the case now.”

When Baron Haussmann reimagined Paris in the 19th century, he made its streets more spacious and airy, and therefore less susceptible to disease and crime. Today there remains a steadfast commitment to prioritising quality over quantity when it comes to designing the urban environment. The draw of the city’s cultural behemoths – such as the recently renovated Tadao Ando-designed Bourse de Commerce – remains world-beating, as does its retail prowess.

All of this, combined with the policies of the country’s most pro-business president in a long time, has helped Paris to draw and foster enough talent to snatch London’s double crown as Europe’s top venture-capital city and its leading technology hub. “Paris lends itself far more to an office-based culture than cities such as San Francisco or London,” says Jordane Giuly, the founder of fintech company Defacto. He points out that the French capital’s gentle density is conducive to cross-pollination between start-ups and preferable to the vast distances that one needs to traverse in its rivals.

That said, even with the recent business boom, property prices in Paris have fallen over the past two years. Though some areas remain pricey, the city has largely kept its soul, in large part due to housing policies that have helped to keep low-income residents and their businesses in the heart of the city. More than a quarter of Paris’s inhabitants live in social housing, while small businesses, such as neighbourhood butchers and the city’s famous independent bookshops, have benefited from measures protecting their existence. This idea of mixité sociale (socially and economically diverse districts) has also helped to inject new life and dynamism into a gastronomic scene that had begun to feel threatened by rivals – and now some waiters, like many of the new business owners, are even happy to speak English. C’est la vie!

1. Population: 2,048,472 (metro: 12,271,794)

2. Average working week: 35 hours (mandated by French law)

3. Number of Michelin-starred restaurants: 123

4. Cycle lanes: more than 1,000km

5. Number of museums within city limits: 136

Click here to enjoy the full Monocle city guide to Paris

Our Quality of Life Conference, which this year takes place in Barcelona, assembles the world’s boldest thinkers, industry leaders and creative talent for a real conversation on the things that matter to us all. Click here for more information and tickets.

2.

Madrid

Best for health

A favourable work/life balance and delicious food are a winning formula in the Spanish capital.

On a sunny Friday morning in late May, Madrileños of all ages roam the counters at Mercado de la Paz, browsing fresh fish caught that morning, glowing red tomatoes and cheese from all four corners of the country. This Salamanca institution is one of dozens of mercados in the Spanish capital – food markets found in almost every neighbourhood that hint at why Madrid’s citizens are such a healthy bunch. The city has the highest life expectancy (86.1 years) of any metropolis in Europe.

These figures are down to a unique combination of assets – meteorological, economic and social. Excellent weather and food, strong intergenerational bonds and a natural gregariousness mean that residents work to live rather than live to work. “Socialising is very Madrileño,” Manuel Martínez-Sellés, the president of the city’s Official College of Physicians, tells Monocle. “Keeping physically and intellectually active benefits both the quantity and the quality of life.”

Then there’s the city’s excellent healthcare. Spain is renowned for its public hospitals, which combine the best in training with an almost unparalleled (in Europe, at least) system of data-gathering. As a result of decades of centre-right dominance, the Madrid region now has the highest private health-insurance coverage in Spain about 37.5 per cent. “Good public-private collaboration often allows for more efficient and decisive medicine,” says Martínez-Sellés. “In Madrid we have the best hospitals in Spain, 11 medical schools (more than many European countries), the nation’s leading biomedical research centres, strong and responsive primary care, shorter waiting lists for surgery than in other regions, very active prevention and early diagnosis programmes, and exemplary out-of-hospital emergency services.”

But Madrileños know that health is about more than medicine. Their wellbeing is rooted in socialising and outdoor activity, and this includes, for many, a regular glass of wine and slice of jamón ibérico. Walk Madrid’s plentiful plazas on any night of the week and you will see children kicking a ball around while the adults enjoy el paseo, the traditional twilight stroll, or knock back a crisp glass of beer. A quarter of Spaniards smoke and alcohol remains a part of daily life but an acceptance of the importance of these things at a social level is part of what makes the people of this city such an outgoing – and therefore longer-living – bunch.

Spanish urban planning has helped communities to flourish and loneliness is less common than elsewhere. “Healthy ageing is about enabling people to continue doing what they value as they grow older,” says Vânia de la Fuente-Núñez, a doctor, anthropologist and expert in ageing. “It shifts the focus away from simply having or not having a disease and instead looks at how well a person functions and feels in their environment.” De la Fuente-Núñez serves on the board of Grandes Amigos, a Madrid-based non-profit that promotes intergenerational relationships and addresses social isolation among older people. The organisation runs a volunteer network that promotes interaction between people of all ages and support for the elderly.

Of course, all of this jollity is more than helped by the weather. With as many as 3,000 hours of sunshine a year, Madrileños are often to be found exercising, jogging or cycling around the city’s 60 sq km of green space, swimming in one of its 25 public pools or playing tennis or padel at one of the 698 public courts. For less sporty residents, simply wandering the city’s streets on a sun-soaked evening is a life-enhancing, and possibly extending, experience.

1. Population: 3,460,491 (metro: 6,798,000)

2. Life expectancy: 86.1

3. Number of municipal food markets: 45

4. Number of medical schools: 11

5. Average retirement age: 65.5 (women), 64.7 (men)

3.

Athens

Best for nightlife

The Greek capital is never boring and one of Europe’s few truly 24-hour cities.

More than 15 years since a debilitating debt crisis, the Greek capital has become the discerning night owl’s stamping ground. The country’s economy grew by 2.3 per cent in 2024, which, while not exactly stratospheric, is enough to elicit envious glances from its Western and Northern European counterparts. Athenians now speak of those dark days of high inflation and unemployment as being in the past and, in hindsight at least, it seems that this ancient city was able to turn adversity into opportunity, kick-starting a cultural renaissance that has transformed abandoned spaces and post-industrial areas into some of Europe’s most exciting nightlife spots.

At 02.00 on a Friday night, people fill Menaichmou Street in the buzzy Neos Kosmos neighbourhood, glasses in hand. Their laughter and chatter compete with a wall of sound emanating from the street’s many establishments, including natural wine bar Epta Martyres and spritzeria Bar Amore. It’s the same story on Meandrou Street in Ilisia, where Junior Does Wine rubs shoulders with Quinn’s; and Vissis Street, once known only for its hardware shops, which is now home to cocktail hub Kennedy among other excellent bars. All typify the way that an infusion of young, creative people from across the globe has invigorated a once slightly sleepy and rundown city. “In the summer, everyone spills out onto the street,” says Eleni Georgiou, a young jewellery designer. “The atmosphere is lively yet laidback. It’s like the whole city becomes one big open-air gathering.”

A relaxed attitude towards licensing laws might be assumed as a given in this part of the world but Athens’ laissez-faire approach is born more of political than geographical circumstances. After the fall of Greece’s military junta in 1974, a country that had been denied individual freedoms was fierce about protecting its hard-won rights.Twenty years later, in 1994, a stern-faced minister for public order, Stelios Papathemelis, introduced a law mandating nightclubs to close at 02.00 to rein-in a perceived air of permissiveness. Contravention of the “Papathemelis Law”, as it came to be known, became a badge of honour in Athens and today clubs, especially in areas such as Exarchia, stay open as long as there are people inside having fun.

A post-pandemic boom in tourism has transformed Athens from a stop-off en route to the islands into a destination city. In 2024, 7.9 million people visited the Greek capital, a 12 per cent increase on the year before. Many of these came to see the Acropolis but others were here to experience a place that is being explicitly marketed as a 24-hour city. The Athens Metro – which is being significantly expanded with the construction of the new Line 4 – runs from 05.00 until 02.00 on weekends. Anyone looking to travel between 02.00 and 05.00 will find that taxis are both cheap and plentiful.

Though an influx of affluent foreigners has led to a rise in prices, especially in the property market, Athens remains affordable compared to other European cities – a glass of wine costs, on average, less than €6. Starting a meal at 22.00 is not unusual for Greeks, especially during the hot summer months, and when you eat late, you drink, dance and go to bed late too. It’s not just the hardcore ravers who leave the clubs at 07.00 in July. Those coming out blinking into the dawn light might take a trip to Metaxourgeio for a restorative spanakopita (spinach pie) or gyro, while, for the more adventurous, there’s always the short metro ride to the beach.

Whereas many other cities, especially in Europe, have been on a trajectory of diminishing nightlife returns over the past 10 years, Athens is dancing to a different tune. As Nena Dimitriou, writer of the weekly “Café-Bar” nightlife column in the Athenian daily Kathimerini puts it, “No one is ever bored in Athens.”

1. Population: 643,452 (metro: 3,638,281)

2. Average price of an Aperol spritz: €7.50

3. Weekend opening times on the Metro: 05.00 – 02.00

4. Average closing time of bars: 02.26

5. Number of stops on the Athens Metro: 66

Click here to enjoy the full Monocle city guide to Athens

4.

Barcelona

Best for urban greening

The Catalan capital is proactive about enacting radical policies and its approach to the environment is achieving solid results.

After three years of drought, the return of rain to Barcelona this spring was more than just a meteorological relief: it marked a moment of renewal for a city that’s doing more than most to stay in step with nature. The Spanish phrase “En abril, aguas mil” (“In April, a thousand rains”) was uttered with smiles, as residents joked about living in London or Paris. And when the sun came back out, Barcelona looked greener than ever, in more ways than one.

Faced with issues such as increasingly regular water shortages, pollution and population density, the city adopted a strategy to green its streets and public spaces. The flagship Superilles (Superblocks) initiative – first proposed by environmental researcher Salvador Rueda and trialled by city hall in 1993 – has rethought car-dominated intersections in favour of people-first places lined with trees, shaded areas and space for community life to blossom.

On a recent morning, the intersection of Girona and Consell de Cent streets, now a bustling square, was busy with people chatting on benches, tourists sipping coffee on the terrace of Bar Betlem and older folks pausing for respite from the sun under a plane tree. In Barcelona, life happens on the street. If you offer residents space to socialise, they’ll use it. The shift away from cars brought less visible but real benefits, including a 22 per cent reduction in co2 emissions, preventing hundreds of deaths each year. Small businesses on newly pedestrianised streets also had an increase in footfall as people chose to walk these greener, cooler, calmer routes. Bird life has benefited too. There are now more than 80 species nesting across city parks.

Alongside the broader Pla Natura scheme for planting is the new Parc de les Glòries, a 4.3-hectare green space with broad promenades and more than 9,000 sq m of vegetation. The redevelopment brought swaths of land into community use, planted more than 1,000 trees and stitched together a new green corridor in the heart of the city. But the strength of Barcelona’s approach is in smaller, more targeted solutions. Participatory digital tools for citizen feedback, such as Decidim, have helped residents to have a bigger voice in shaping their city. “Barcelona also shows how micro-greening solutions, such as pocket parks and green roofs, can offer access to nature even in compact areas,” says Amalia Calderón Argelich, a post-doctoral researcher at the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability. “Inclusive design practices – such as improved lighting, accessibility and safe park layouts – are adaptable models for dense cities.”

Liveability is the aspiration but, as in many great cities, there is a tension between plans and outcomes. In the Poblenou neighbourhood, where the 22@ project transformed an industrial zone into a gleaming district of green avenues and modern infrastructure, property prices have soared by almost €3,000 per square metre in just 10 years. With this shift has come accusations of gentrification with the loss of the neighbourhood’s former identity and the displacement of its residents. “Though greening plans are ambitious, gaps persist,” says Calderón Argelich. Gentrification and “touristification” remain hot topics as every new park can trigger a rise in house prices. Without some protective policies and civic oversight, says Calderón Argelich, well-meaning projects risk undermining the equity that they aim to promote. “Resilience depends on protecting these frameworks from political volatility.”

1. Population: 1,600,000 (metro 5,300,000)

2. Total area of municipal green spaces: 2,784 hectares

3. Total reduction of carbon emissions due to the Superblocks programme: 22 per cent

4. Number of stations on Barcelona Metro: 165

5. Total distance of cycle lanes in city: 268km

5.

Vienna

Best for housing

The Austrian capital’s architecture and social housing stock are the envy of the world.

In October 1930, Vienna’s socialist mayor, Karl Seitz, gave a speech at the opening of a new housing block, the Karl-Marx-Hof. “When we are no longer here, these stones will speak for us,” he said. Today the building that he was inaugurating is probably the best known of Vienna’s Gemeindebauten, social housing that has become emblematic of the city’s high quality of life. Nearly a century on, some 6,000 Gemeindebau flats are still built every year, in a continent where many cities have given up on the principle of social housing. The new ones are less monumental than their forebears but the tradition of naming them after eminent public figures remains. Karl-Seitz-Hof opened in 1931.

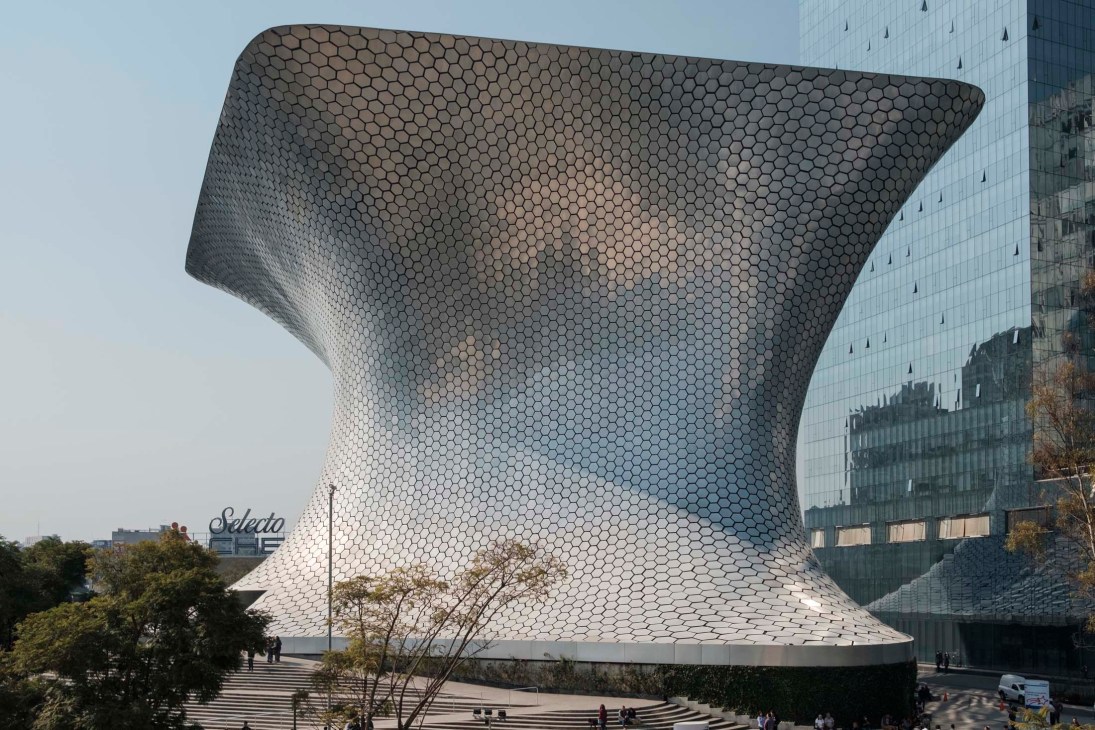

Housing authorities have also stuck to the principle of distributing council flats across all districts to prevent economic segregation. Another key plank of urban cohesion is the comparatively generous income cap for applicants: €59,320 a year for a single person and €88,400 for a couple at the time of writing. The upshot is that more than half of Vienna’s two million residents live in some form of subsidised housing, whether in Gemeindebauten or state-supported co-operatives. One of the better-known examples of the latter is the sprawling Alterlaa complex (pictured) in the city’s south, home to about 10,000 people and an architectural pilgrimage site for many visitors to the Austrian capital.

Freelance journalist Susanne Jäger has lived in her 43 sq m council flat in the heart of old Vienna since 2014. She also spent part of her childhood in municipal housing. “The Gemeindebau programme has always been part of my life,” she tells Monocle in her Fischerstiege apartment, which is across the road from Vienna’s old city hall. On the ground floor is an office of the Social Democrats – the party of Seitz and the current mayor, Michael Ludwig – alongside a bookshop and an after-school care centre for residents. Jäger hadn’t planned to stay long but the low rent – about €370 a month without utilities a decade ago, now €420 – persuaded her otherwise. “I was never offered a better deal,” she says. She is also struck by the city’s efforts to support tenants who are in difficulty. In her hallway, a poster from city hall reassures residents that they won’t be left in the lurch if they fall behind on payments. “Vienna is the only landlord that tries to keep you in rather than kick you out,” says Jäger.

Of course, social housing is only one strand of Vienna’s mixed housing stock. Roughly a third of the population lives in privately rented flats, with one in five of those in buildings constructed before 1945 – the so-called Altbauten (“old builds”). Most are solidly built, with thick walls, high ceilings, grand tiled entrances and fabulous façades (especially the Jugendstil buildings from the 1890s and 1900s). Balconies or terraces are rarer but there’s often a large courtyard, or Hof, and sometimes a private back garden. The Altbauten are highly sought after, with prices per square metre ranging from about €6,200 in the eighth district to €19,000 in the first. Rents, however, are far more manageable, hovering between €14 and €20 per square metre for both old and new.

Vienna is still very much a city of renters and their rights are staunchly defended, especially in older properties. Homeownership is fairly modest compared to other European capitals, accounting for less than 20 per cent of the population – though that might soon change. Though construction has slowed somewhat, attractive new developments are springing up citywide: in the Nordbahnviertel, near the Danube, on the site of an old railway station, and in Aspern Seestadt on the northeastern fringe. The latter is one of Europe’s largest urban development schemes. In a city where housing is treated as a right rather than an asset, these particular Neuebauten attract less local ire than they might elsewhere.

1. Population: 2,005,760

2. Average proportion of income spent on rent (for a one-bedroom flat): 21 per cent

3. Proportion of population in social housing: 60 per cent

4. Average rental cost: €3.87 per square metre (social housing), €10.40 per square metre (private sector)

5. Number of new social housing units built per year: 6,000-7,000

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s full city guide to Vienna

6.

Zürich

Best for mobility

The city that spawned its own transport model isn’t resting on its haunches.

In 2024, Verkehrsbetriebe Zürich (VBZ), the body that owns and operates Zürich’s transport network, recorded approximately 304 million annual passengers across its buses and trams – a 2.1 per cent increase on the previous year. For Switzerland’s largest city, which has spawned a set of much-imitated but never bettered mobility policies known collectively as the Zürich Model, it was further proof that superiority need not induce complacency. The most appealing cities reflect the best things about their nations (as most of this line-up can attest) but perhaps nowhere is that more in evidence than on Zürich’s transport network, which exudes a Swiss air of efficiency. “Where else do passengers greet you when they’re getting on and off?” asks Sinan Yigitler, a bus driver who moved to Zürich from Germany with his family. Could it be that a calm, clean and cheap transport experience makes passengers more cheerful?

An enduring symbol of Zürich is its tram network. Pale blue and white, these sleek road trains glide through leafy boulevards and along lakefront promenades, the doleful clang of their bells and the soft whoosh as they pass providing the city’s muted soundtrack. Since 2002, Zürich’s buses have run for 24 hours on weekends, ferrying home the stragglers from bars and clubs as the city settles into silence.The Zürich model grew out of a realisation on the part of the city’s government in the 1960s and 1970s that it had to offer public transport of a high-enough standard to tempt commuters out of their cars and so avoid gridlock on its streets (nearly 280,000 people commute into Zürich every day a number not far off the city’s population of 360,000).Today, 327 intersections are equipped with sensors that detect approaching vehicles and adjust signals to prioritise the transit of trams and buses over cars.

But the city’s ambitions go well beyond trams and buses. The Zürich Model places great value on modal split, meaning that all facets of the network must be constantly improved to ensure the vitality of the whole. Under the government’s 2030 bike plan, the number of cycle lanes and cyclist-first traffic lights are due to be expanded, while its 2040 mobility strategy focuses on connecting the fast-growing northern and western suburbs to the rest of the city. Projects such as the Tramtangente Nord, a planned orbital tram line that binds outer districts without passing through the city centre, aims to improve capacity where it’s needed most.

“We need to redistribute street space to give more room to pedestrians and cyclists,” says Simone Brander, the head of Zürich’s civil engineering and mobility department. This ethos is deeply felt by the people who operate the system too. “It’s an important part of my life and the people here are like my second family,” says Astro Ajvazi, a VBZ instructor who trains the next generation of tram operators.

1. Population: 448,664 (metro: 1,450,000)

2. Annual public transportation ridership (2024): 665 million passengers (11 per cent increase on the previous year)

3. Proportion of tickets purchased on mobile phones: 70 per cent

4. Number of sensors monitoring traffic throughout the city: 4,500

5. New cycle lanes currently planned or under construction: 130km

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s full city guide to Zürich

7.

Mexico City

Best for conviviality

Mexico City is attracting those seeking quality over quantity.

For many people in Mexico City, the weekend officially kicks off at about 14.00 on a Friday. In the leafy neighbourhoods of Condesa and Roma, streetside cafés and restaurants fill with residents and visitors alike, seated at tables spilling onto the pavements. Food has always been an important part of Mexican culture and people here have access to a good bite no matter their budget, whether it’s tacos from a street vendor or silver service. A long lunch is more than just eating: it’s an opportunity to savour time with friends and family, embracing the tradition of sobremesa – an unhurried meal in which diners linger around the table for hours.

Mexico City’s laid-back attitude, which extends far beyond the dining table and into everyday life, is luring many from afar. The city’s population grew by 600,000 between 2019 and 2023 – much of that influx from the US and Canada, countries to where Mexicans have traditionally emigrated. It’s proof that the city’s way of life is catching on. “The people here value quality of life above many things,” says Adolfo López-Serrano, a resident and founder of communications company Base Agency.

Despite being one of the biggest and most hectic cities in Latin America, many neighbourhoods here, such as Condesa and Coyoacán, offer a small-town feel, with inhabitants waking to the sound of birdsong. “The urban fabric is very nice and there’s also great architecture,” says Rodrigo Rivero Borrell, founder of property developer Reurbano. He notes that neighbourhoods around the Paseo de la Reforma were developed consciously, with wide avenues.

“The city is designed for movement, with walkable streets and good public transportation in the central areas,” says López-Serrano. There are almost 400km of bike lanes, which is remarkable for Latin America, and the Metro, with 12 lines covering more than 226km, is the second largest on the continent. The city also has one of the best-connected airports in the region, with direct flights to more than 100 destinations, including London, Los Angeles, Madrid, New York, São Paulo and Tokyo.

Outsiders tend to find Mexico’s capital very inviting. “Being a Latin society, it’s a welcoming place,” says Rivero Borrell. “People want to engage.” It’s also ideal for those seeking to build a business. López-Serrano describes it as “a city where chaos and order happen at the same time, creating the perfect playground for creatives and entrepreneurs”. He adds that in Mexico City, “You can be scrappy and resourceful, and push boundaries. Yet the standards for design, culture and innovation are remarkably high.”

Certain neighbourhoods are astonishingly green. In an effort to improve air quality and mitigate the effects of climate change, more than 44.2 million trees, shrubs and ground covers have been planted throughout the city since 2019, according to Mexico City’s environment ministry. “The central areas are well serviced in terms of parks and public spaces to maintain a healthy lifestyle,” says Rivero Borrell. Being outdoors is woven into city life and you’ll always find people walking their dogs, exercising or dancing salsa in one of the 244 parks or plazas here. There are few better ways to foster a sense of community.

1. Population: 9,209,944 (metro: 23,146,802)

2. Typical closing time for bars: 03.00-04.00 (on weekends)

3. Number of stations on Mexico City Metro: 195

4. Average price of a house: MX$3.9m (€178,000)

5. Number of public museums: More than 180

Enjoy Monocle’s complete city guide to Mexico City here.

8.

Lisbon

Best for safe streets

Crime rates continue to fall in this sunny metropolis by the sea.

Speak to one of the hundreds of thousands of Brazilians who call Lisbon home – the largest immigrant community in Portugal – and safety will almost certainly emerge as one of the reasons for their move. In this respect, Lisbon has become the gold standard for many. Europeans and Americans who have recently flocked to the city also cite security as an important factor in staying. “I can walk down any street at any time without having to look behind my back,” says George Dellinger, who moved here from New York in 2022. “I don’t feel vulnerable. There’s a sense that people look out for each other.”

Lisbon has evolved over the past decade from a somewhat sleepy town into a dynamic European capital and it has impressively done so without compromising on the safety of its residents. Crime in the capital is consistently low compared to other European cities; Portugal’s latest annual homeland security report indicates that in 2024 there was the steepest drop in the crime rate (excluding the anomalous pandemic years) in more than 10 years: a fall of 7.6 per cent in Lisbon’s metropolitan area. It also points to a 1.8 per cent decrease in violent crime, with even bigger drops in the city proper.

That said, statistics don’t always tell the full story. Safety is also a collective sentiment and, recently, a few widely publicised violent incidents have rattled some sectors of society and inflamed political rhetoric. Lisbon’s mayor, Carlos Moedas, has acknowledged the public’s unease and called on the government for increased policing in the city.

But, as ever in Lisbon, a lot of emphasis has been placed on community policing, a preventive and participative approach that has garnered attention from across the globe. In contrast to the stock response of cities faced with security issues – more CCTV or increasingly heavy-handed policing – Lisbon invests in more integrated forms of safety that put trust and a human presence at their centre. Police officers are assigned to neighbourhoods for the long term, fostering familiarity with citizens and partnerships with neighbourhood associations and social services. The constant dialogue between these groups means that the police are better equipped to address problems as they arise and deal sensitively with issues around drug use or homelessness through dialogue.

Like any city shaped by tourism, Lisbon has pockets where petty theft is common, especially in the historic downtown areas. But when it comes to the kind of ambient, everyday safety that allows one to move through public space without thinking too much about it, Lisbon continues to offer a rare kind of freedom. An intuitive way to grasp this is by noticing how schoolchildren make their way through the city. They’re often unaccompanied, navigating public transport and streets with an ease that recalls a different era. For parents it’s a powerful indicator. “The number of times I’ve left my purse on the pram while running after my boy in the park… I would never think of doing that in London,” says Perrine Velge, who moved from the UK capital to Lisbon in 2020.

Another indicator can be seen when going out at night. Like other Mediterranean cities, Lisbon has a late-night culture that is dominated not by heavy-drinking young people but a relaxed mix of ages. Eating out, strolling home or sharing a glass of chilled white port in a neighbourhood bar remain part of everyday life, unmarred by disorder. Feeling physically safe in some Western cities is no longer taken for granted, if indeed it ever was. Lisbon is a rare outlier.

1. Population: 567,131 (metro: 3,049,222)

2. Number of municipal police officers: 6,700

3. Murder rate: 1-2 per 100,000 inhabitants per year

4. Year-on-year reduction in reported crimes: 7.6 per cent

5. Number of additional CCTV units planned this year: 99

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s full city guide to Lisbon

9.

Tokyo

Best for cleanliness

Tokyo’s spruce streets and responsible citizens set the benchmark.

For a city of 10 million people – and that’s just the 23 central wards – Tokyo is bafflingly clean. (The population balloons to 44 million if you take in the greater Tokyo area.) To understand why, look at how the Japanese capital operates in the morning. Rubbish vans trundle along residential streets, with binmen jogging alongside their vehicle as they grab bags of meticulously separated household refuse. Meanwhile, an army of kanrinin, the caretakers who look after Tokyo’s apartment blocks, mop entrances and put out rubbish. Shopkeepers and café owners spruce up the area in front of their establishments, picking up any stray litter and cigarette ends (banning street smoking has improved that situation no end).

Volunteers are also out in force. In fashionable Omotesando, a band of hairstylists from some of the dozens of salons in the neighbourhood are in green bibs, picking up litter before opening time. Over by Shibuya station, another group of volunteer helpers – schoolchildren and pensioners – are tackling the detritus on one of the world’s busiest pedestrian crossings.

The lack of street bins is no surprise to anyone who lives here (most disappeared after the deadly sarin gas attack in 1995) and people expect to have to look after their own litter. The sticking point has come with the arrival of unprecedented numbers of tourists who are not necessarily on the same page garbage-wise. It’s not that visitors are looking to dump rubbish but they’re often unsure what to do with their plastic cups and bottles. Overflowing bins are never a good look so refuse-flattening smart bins are being introduced to busier streets and tourist sites.

Public toilets have had a major upgrade in Shibuya with the Tokyo Toilet project, in which 16 creators (including architectural A-listers such as Tadao Ando and streetwear legend Nigo) designed public conveniences that not only look good but come equipped with Toto Washlets and are kept spotlessly clean by a team of people who wear natty boilersuits (as seen in Wim Wenders’ film Perfect Days). Architect Kengo Kuma designed one comprising five wooden huts in Shoto Park. He called it a “public toilet village that is open, breezy and easy to pass through”. The project’s organisers consider clean, well-lit, fully accessible public toilets essential to any city and even “a symbol of Japan’s world-renowned hospitality culture”.

As in every city, there’s graffiti in Tokyo (though not in the same quantities as elsewhere). Clean & Art, a group led by artist Ken Sobajima, is on a mission to eradicate the blight. Passers-by applaud Sobajima and his team as they paint over unwanted scrawls and restore walls. “I used to think that nobody cared,” he says. “But once I talked to people, I discovered that everyone was bothered by it.”

As with most aspects of daily life in Japan, there are deeper philosophical reasons for this preoccupation with spotlessness. Shinto, Japan’s native religion, demarcates clean and unclean spaces, a division that affects everything from the sumo ring to the home. Children absorb this distinction between clean “inside” and unclean “outside” early.

All of this isn’t to say that there’s no rubbish in Tokyo but, overall, it’s much tidier than other cities of a comparable size. Tokyo spends a fortune on keeping things presentable. The Clean Authority of Tokyo’s waste management budget for the central wards is ¥105bn (€640m) this year, of which ¥83bn (€507m) is dedicated to cleaning. But the secret to the city’s sparkle is that it’s not simply the work of city employees: it’s a collective job.

1. Population: 14,000,000 (metro: 41,000,000)

2. Number of public toilets: 53 per 100,000 residents

3. Annual municipal solid waste produced: three million tonnes

4. Recycling rate: 20 per cent (nationwide)

5. Number of municipal green spaces: 159

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s full city guide to Tokyo

10.

Tallinn

Best for start-ups

Estonia’s capital continues to attract entrepreneurs seeking Nordic-style living without the high price tag.

The Estonian capital is well known for its leafy streets, medieval architecture and raucous nightlife – but it’s increasingly gaining a reputation for its close-knit entrepreneurial network and world-leading digital infrastructure.This is aided by the fact that nearly everyone speaks English, rents are affordable and it’s a mere 10-minute drive from downtown to Tallinn airport, which has direct flights to 60 international destinations. Throw into the mix Europe’s highest number of unicorns per capita, a dense network of venture-capital firms and a steady pipeline of technology talent, and Monocle’s 2025 Best for Start-Ups award feels like a shoo-in.

“Estonia is particularly good for digital infrastructure,” says Martin Sahlen, who moved from New York to Tallinn to launch fintech business Alvin.ai. “It’s a very entrepreneurial country and there is less red tape.” He set up his company in the district of Telliskivi, the epicentre of Tallinn’s vibrant start-up scene, where co-working spaces such as Lift99 sit alongside excellent and affordable restaurants and bars, such as Pudel and Juniperium, and a growing number of museums and cultural venues, including Fotografiska.

Another draw for entrepreneurs is Estonia’s e-residency programme, through which non-nationals can open and manage an EU-based business entirely online, no Estonian address or presence required. Almost everything, from company registration to tax filings, is handled digitally, which means that the actual starting-up process can take just minutes. Taxes, meanwhile, are only applied when profits are distributed – a boon for early- stage reinvestment.

Yet Tallinn’s real draw is its people. “We are really like a community,” says Irina Tokareva, a hub administrator at Lift99. “All foreigners are friends from the first minute.” According to Tokareva, approachability defines the culture here. “You don’t need to book a call through two assistants,” she says. “You can just write to them and say, ‘Hey, I’m building this and I’d love to show it to you,’ and they’ll answer.”

This openness extends to the top of government. Like his predecessors, Estonia’s prime minister, Kristen Michal, has hosted round tables with start-up founders to better understand their needs. Public support is structured too: Startup Estonia, a government-backed initiative based in Ülemiste (another business zone that’s home to dozens of start-ups), plays a central role in connecting newcomers to networks, resources and funding. “If you look at the people who are building new start-ups, they often have backgrounds in multibillion-euro businesses such as Skype, Wise, Pipedrive and Bolt,” says Mirjam Kert of Startup Estonia. “Since 2010, more than €4.5bn has been invested in Estonian start-ups, 92 per cent of it from foreign investors.”

“I chose Estonia because it’s in the same time zone as Kyiv and it was really cheap compared to, say, Berlin or London or New York,” Ukrainian founder Alexander Storozhuk, who relocated his media-technology firm PRnews.io here, tells Monocle in his office at Porto Franco, looking out at the dozens of boats bobbing in Tallinn’s sunny harbour. Safety and quality of life were decisive factors too. “My eight-year-old daughter walks home alone from school and I’m always confident of her safety,” says Storozhuk. Between the agile public services, a highly international founder base and the Nordic-style liveability (minus the price tag), Tallinn punches well above its weight. For founders looking for speed, support and a city where big ideas travel fast, Estonia’s capital is a smart place to start.

1. Population: 461,000 (metro: 550,000)

2. Number of international destinations served by airport: 44

3. Average top-tier office rent: €22 per square metre (2023)

4. Personal income tax: 22 per cent

5. Average price of a cappuccino: €3.60