Seville, the ‘frying pan of Europe’, holds the secrets to managing the blistering summer heat

As temperatures continue to soar, heatwaves have become a Spanish tradition. The city of Seville is drawing on both ancient knowledge and cutting-edge science to keep its citizens cool.

On a mid-afternoon in late May, people cram themselves into the narrow strips of shade between buildings in Seville’s Triana district. This sort of basic temperature regulation comes naturally to Sevillanos. Heat is baked into the city’s history and therefore its architecture – from the Islamic-era narrow streets and cool internal courtyards to the shaded bus stops and street sprinklers of the Andalusian capital’s more recent past. But Seville is getting even hotter and new urban interventions are required. In May, the city recorded three consecutive days with temperatures of over 40c for the first time on record – proof that human-driven climate change is ratcheting up the heat in a city already known as the “frying pan of Europe”. By 2050, it could see summer highs of 50c and an estimated 20 per cent reduction in rainfall, a deadly combination for its metropolitan population of 1.5 million people. In July 2022, when the mercury topped 42c for several days, 132 people died as a result of the temperature.

As a consequence of these challenges, Seville, which is home to world-leading experts on extreme heat, is leading the charge when it comes to innovative climate-mitigation strategies. At the forefront of this mission is a sleek underground chamber that’s filled with what resemble dozens of metal air ducts. These are qanats, subterranean aqueducts that have been used since the third century bce to improve irrigation and lower ambient temperatures.

We are at the Cartuja Qanat development, a council project overseen by the University of Seville, that is channelling the city’s Moorish past to help solve its modern ills. Qanats became widespread in the Middle East because of their effectiveness in diverting rainwater from higher altitudes to semi-arid land, where it could be used to irrigate crops or provide drinking water for animals. “We’re using the ancient Persian qanat idea to create a 21st-century version,” says María de la Paz Montero Gutiérrez, a researcher on the project. Seville’s modern qanats snake through buildings and energy infrastructure, where their metal surfaces emit cold air that has been found to lower ambient temperatures by between 8c and 9c. The ducts converge at what was once the site of Seville’s 1992 World Expo. Montero Gutiérrez says that councils from across Spain have come to the city to learn more. There are plans to expand the qanat system across the river and into Seville’s city centre.

Another project that aims to increase Seville’s water supply and harness its potential for temperature regulation is the Life Watercool scheme. This EU-funded project creates channels that collect, store and pump water run-off into public spaces. It is leading the transformation of Seville’s Cruz Roja Avenue in the city centre from a traffic-choked thoroughfare into a shaded pedestrian zone dotted with water features designed to provide respite for citizens and visitors during the sweltering summer months.

While Cartuja Qanat and Life Watercool focus on infrastructural heat mitigation, Prometeo Sevilla is concerned with the psyche. In 2022 the city became the first in the world to name and categorise heatwaves – a policy anointed when Heatwave Zoe struck in July that year. The programme’s aim is to raise awareness of these increasingly common extreme-weather events. “The idea is simple,” says José María Martín-Olalla, professor of physics at the University of Seville and a Prometeo Sevilla spokesperson. “It’s the same reason why they give names to more adverse winter-type phenomena – so that people take certain precautions.”

The programme’s team is made up of university faculty and climate scientists from the Arsht-Rock Resilience Centre. Their job involves identifying future heatwaves, naming them and then communicating the attendant risks to the city council. But while the naming part has proved effective in helping people to remember them post-facto (early studies show that a third of participants remembered named heatwaves over unnamed ones), the work is complicated by differing definitions about what constitutes such an event. “If you’re talking about a hurricane, you see the eye of the storm,” says Martín-Olalla, explaining that the classification of extreme-heat events differs even within Spain. “A heatwave in Seville isn’t the same as one in Bilbao.” In the former, temperatures must exceed 40c for three consecutive days, while in the cooler, greener north of Spain, where average summer temperatures hover near 20c, the threshold is less rigid, though it would almost certainly be lower. The challenge is to educate Sevillanos on how to react so that the now traditional summer heatwaves do not necessarily lead to loss of life. In this way, the city could help to educate a warming world about how to cope with higher temperatures.

Facing up to these challenges doesn’t just involve large-scale planning. Seville also deploys more discreet measures that allow people to go about their day in comfort. Municipal councils open up public libraries, schools and sports centres when it’s particularly hot so that locals can take advantage of on-site air-conditioning systems. In the city centre, roads such as Calle Sierpes and Calle Tetuán are covered by awnings hung between buildings that allow shoppers to move along the grand, polished-stone streets beneath a layer of shade. In the bohemian Alameda district, as the sun begins its daily descent, the heat lingers. In one plaza, locals sip cañas and smoke cigarettes in the shade. Then, all of a sudden, tiny metallic water jets hidden in the square’s many parasols hiss into life, emitting a thin, glittering mist. By 20.00, though the mercury is still showing 27c, the atmosphere has cooled and young and old have begun their twilight perambulations. This city, so used to heat, is getting used to heat mitigation too.

Three ways to cool down your city

Let buildings breathe

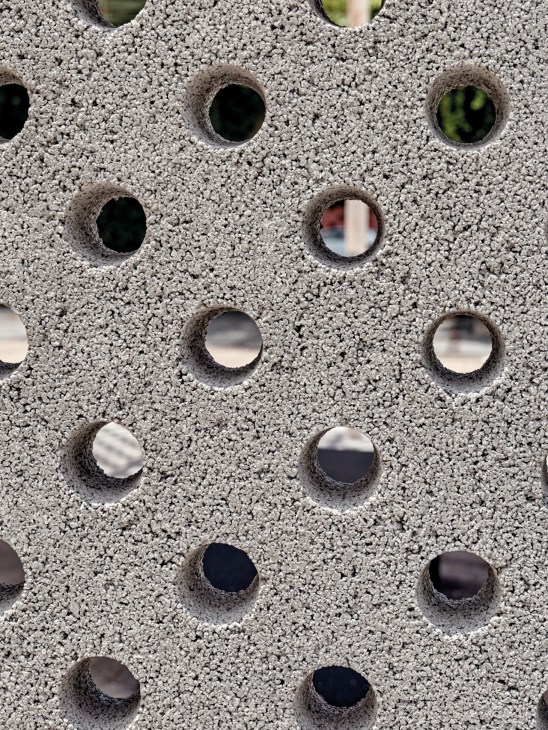

In Abu Dhabi, new buildings draw inspiration from traditional mashrabiya screens to ventilate naturally, while Copenhagen mandates green roofs on its new builds.

Plant more trees and get residents involved

Freetown in Sierra Leone has launched “Freetown the Treetown”, a programme that pays residents to plant and monitor trees and mangroves, engaging the community in a restorative activity.

Build in cooler colours

Black absorbs more heat than other hues, so why not change the colour of asphalt in cities? There’s a reason why residents of Greek islands have long whitewashed their buildings.