How to tap nature’s chilling effect for a sustainable way to cool urban areas

The hum of power-hungry air conditioners has become the soundtrack of summer in the hottest cities. The architect behind a Gold Lion-winning pavilion at Venice Biennale shares a possible solution.

Some of the world’s first air-conditioning units were installed in the 1930s in the offices of Bahrain’s national petroleum company, Bapco, shortly after the nation struck oil. Today energy produced by oil is still used to alleviate the effects of rising temperatures, which are a consequence of drilling and burning it.

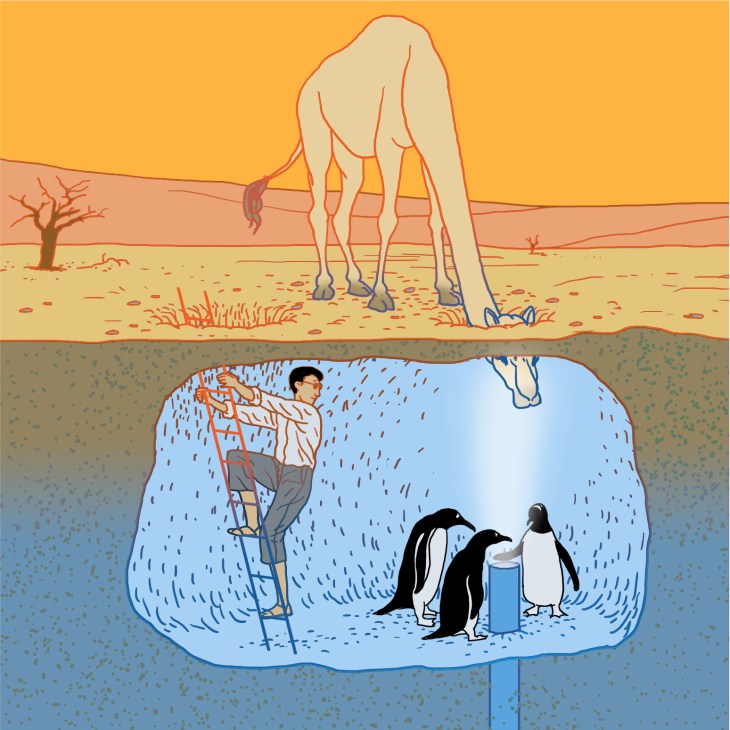

But for the Heatwave exhibition at the Venice Biennale’s Bahrain Pavilion, I came up with a new public ventilation and cooling system – alongside engineers Alexander Puzrin and Mario Monotti – that could be deployed in the region and globally. The design is very simple. A metal pole holding up a square canopy is sunk into the ground and points up to the sky like a chimney. The technology is similar to the geothermal wells used to heat houses in northern Europe, except that instead of water, air is being pumped. In the Gulf, summer temperatures reach nearly 50C but if you dig 15 or 20 metres below ground, you reach a layer that has a stable year-round temperature – in Bahrain, this is about 27C. The pipe brings hot air underground to cool it, then distributes it through “air showers” hidden in the canopy. We needed only one low-energy ventilation pump to cool the entire covered space.

My idea came from an elemental principle: the axis mundi, or the connecting line between the ground and the sky. Trees use their roots to tap into cooler soil and can release heat as excess moisture through their leaves. Similar ideas can be found in the traditional architecture of the Gulf region, where badgir chimneys capture the wind and direct air inside homes. Food that can be affected by heat is often stored in cooler semi-underground tunnels. These ancient systems use simple thermodynamic principles to deal with a hot climate with no need for an external energy source.

In the Gulf today, people rarely leave air-conditioned indoor spaces. This results in high energy consumption; meanwhile, the appliances only work in rooms that are closed to their surroundings. Our pavilion instead tries to adapt to the context by creating a microclimate without walls. Anyone with even a passing grasp of how hot air rises can see how it works. Instead of building protected boxes for people to live in, we should try to understand a place and work with natural principles.

In the future a large part of the island of Bahrain could be almost uninhabitable in the summer. Before the modernisation of the country, people living there would move to cooler parts of the mainland for the season and then return in the autumn. This type of migration has been crucial in many regions across the world. Today we are hemmed in by private property, jobs and the commitments of the modern world. We are confined in one space but not really able to exist sustainably. We must reconsider how we protect ourselves in negotiation with the environment, rather than by treating it as the enemy.

Berlin-based Faraguna studied architecture in Venice. This essay is from the 2025 Venice Biennale special edition of The Monocle Companion. As told to Monocle’s design correspondent, Stella Roos.

Read next:

Seville, the ‘frying pan of europe’ holds the secrets to managing the blistering summer heat