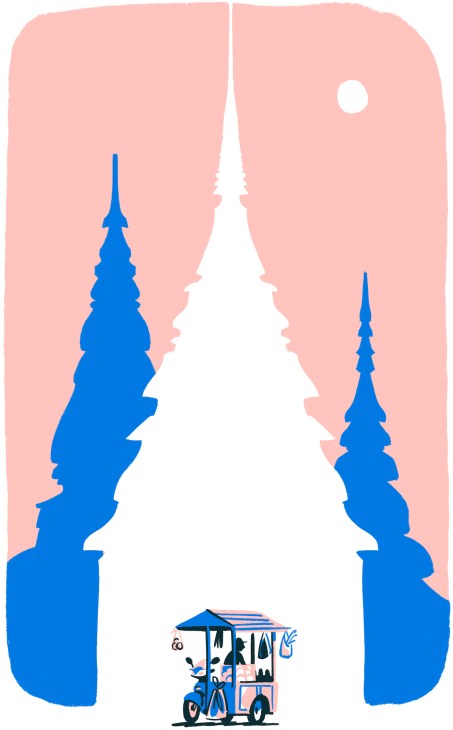

How informal “architectural bastards” could shape Thailand’s urban future

How can architecture better reflect a country’s real character? Thai designer Chatpong Chuenrudeemol shares how shanty towns, love motels and street carts reshaped his practice, and his vision for Southeast Asia.

After graduate school in the US, I moved to Bangkok, a city that never failed to energise me during my summer visits. I soon discovered, however, that a Western architectural education didn’t necessarily mean that I could do great work in Thailand. The University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard offered knowledge and experience but not the sort that spoke directly to the culture or climate of my homeland. I had to learn those things from scratch.

To sequence Thailand’s design DNA, I needed to look beyond the clichés of grand palaces, stilt houses or skyscrapers. My inquiries led me to places to which most architects wouldn’t give the time of day: shanty towns, love motels and temporary interventions. Chancing upon these adaptations and instances of architectural ingenuity led me in 2012 to found Bangkok Bastards, a research project documenting responses to everyday problems: a makeshift bench, a street-vendor’s cart, an improvised shack in a neighbourhood slum.

To me, an architectural “bastard” is a structure with no traceable lineage, formal cultural history or design theory to legitimise it. Nonetheless, they serve a vital purpose and offer a window into a world. Many see these structures and objects as eyesores or unworthy of documentation. But they are pure, intuitive and at times humorous responses to real problems. They’re also constantly being adapted. I photographed, measured and drew them. By recording these creations, I felt that I was giving them respect. Everything is rendered to scale, with the construction techniques that enable these designs recorded in detail, to be used as a source of inspiration.

One of the fruits of my research was the Samsen Street Hotel project in Bangkok, set in a former love motel – one of the city’s long-standing typologies. I wanted to turn this dark, secretive structure into a public space that connects with the street. To do so, I took inspiration from construction workers’ temporary dormitories, where corrugated zinc sheets are combined to create two-storey quarters. The ventilation is improved by a quasi-veranda made using a scaffolding of wooden poles – a multipurpose outdoor space for cooking, socialising or drying laundry. Adapting this idea, I created a soi (vertical alley and stage), a rabeang (street terrace) and a nahng glang plang (outdoor movie theatre). Today these host hawkers and performers, and offer spaces for people to linger.

The kind of home-grown architecture documented by Bangkok Bastards isn’t limited to the capital, so the idea soon outgrew the city. Now my Rural Crossbreeds project focuses on the Thai countryside, particularly among paddy fields and fruit farms, while Indigenous Hybrids looks at the Karen population in Ratchaburi province. I recently collaborated with textile artist Prach Niyomkar and Chulalongkorn University on the design for Indigo Loom House – an open-air craft workshop in Sakon Nakhon, a neighbourhood in Isaan known for rice cultivation, textiles and indigo dyeing. It incorporates wooden columns, beams and rafters from vernacular stilt houses, as well as wooden components salvaged from looms, warping boards and spindle wheels. The mix of elements creates something altogether original. The project, I hope, shows that it’s possible to come up with hyper-local designs anywhere and everywhere. (Perhaps an energetic reader might do the same for their street, city or province.)

I’m a designer, not a cultural anthropologist or social activist. My work on an object or site offers perspectives on real life that academia, textbooks and the design media often miss. These grey areas conceal an alternative world of solutions to common problems and a catalogue of fresh design ideas. What’s more, these informal creations are an antidote to the kind of trend-following global architecture that has contributed to the creation of samey cityscapes across the planet. Thailand’s architects should move beyond their reliance on sterile forms copied from elsewhere by searching for more authentic, personal forms and solutions that draw from our unique design DNA.

The Bangkok Bastards project offers a roadmap for Southeast Asia’s next generation of architects, showing ways of working that might result in designs that are properly rooted in place, climate and culture. You don’t always have to look far for inspiration. Sometimes you just need to look more closely at what’s already at hand

About the writer

Chatpong Chuenrudeemol is the founder of Bangkok-based design practice Chat Architects. In 2020 he received the Silpathorn Award, an annual prize recognising outstanding living Thai contemporary artists, including those in the field

of architecture. For this essay, he spoke to Monocle’s Singapore correspondent, Joseph Koh.