Model: Ikken Yamamoto

Grooming: Kenichi Yaguchi

Producer: Shigeru Nakagawa

Ulaanbaatar’s Chinggis Khaan International Airport gleams in a lunar landscape that’s bare but for a few bands of roaming animals. On the drive into town, Monocle’s fixer and translator, Batbileg “Babi” Sukhbaatar, cheerfully informs us that the highway connecting Mongolia’s capital to its new airport – both opened in 2021 and built with Japanese money – is the first in the country on which it is illegal to ride a horse. We barely see another soul, hoofed or otherwise, until we hit the city and the traffic.

At 07.00 on a Sunday, Ulaanbaatar, the capital of the second-least densely populated country on Earth (after Greenland), is in gridlock. It is a cliché to describe somewhere as a land of contrasts. But despite Mongolia having fewer people per square kilometre than almost anywhere else, its capital, where over half of the population lives, is badly overcrowded, with almost comically awful traffic. Though it has a proud culture of nomadism and a religion, Shamanism, devoted to the worship of nature, Ulaanbaatar is the world’s most polluted capital, while nearly 100 per cent of Mongolia’s exports come from the extraction of abundant natural resources (mostly coal, lithium and copper). And while it is a young country – more than 65 per cent of the population is under 35 – this vast mineral wealth is concentrated in the hands of an aged oligarchy.

That said, a few of these same problems might be viewed, in economic terms at least, as consequences of success. Mongolia is rapidly urbanising because the economy is growing: its gdp per capita recently surpassed $5,000 (€4,500). Its modern rulers have been canny, leveraging Mongolia’s resources to attract money from its neighbours while selling itself to Western nations as a democracy in need of support in a part of the world not famed for such things – a tactic known as the “Third Neighbour” policy.

Indeed, with the immediate neighbours that Mongolia possesses, its leaders need to be canny. As Luvsannamsrai Oyun-Erdene, the country’s 16th prime minister since it transitioned from a communist dictatorship to a parliamentary democracy in 1990, puts it, “Mongolia has great peculiarities as it is located between China and Russia – 95 per cent of our exports go to China and we are 100 per cent reliant on Russia for our energy.” It’s a tricky position to be in and one that has been made more difficult through Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s increasingly confrontational foreign policy. So far, Mongolia has managed to navigate these choppy geopolitical waters but as the fallout from Western sanctions drifts across its northern border, its economic dependency on Russia is beginning to sting.

Moscow’s ejection from international payment systems has made it difficult for Ulaanbaatar to pay for its energy, while Mongolia’s treasury has missed out on “navigation fees” from airlines now banned from Russian airspace. Monocle’s journey to the country demonstrates the complicated nature of this new dispensation. Waiting to take off in Istanbul, the plane’s simulated route map shows a northeasterly trajectory directly over the Crimean Peninsula. “That can’t be right… can it?” we ask the man sitting next to us. It wasn’t, thankfully. But by journey’s end, the jagged nine-hour-long green line on the screen served as testament both to the circuitous nature of our route and the very literal way the rest of the world has found around the Ukraine conflict. It’s a circumnavigation that Mongolia does not have the luxury of.

On top of the economic repercussions of the war, which included inflation of nearly 20 per cent last year and a consequent 20 per cent drop in the value of the Mongolian togrog, thousands of men, mostly from the Russian republics of Buryat and Tuva that border Mongolia, have fled south to avoid conscription. “Maybe 12,000 Russian men have come here since the war began,” says Yury Kruchkin, a Russian journalist based in Ulaanbaatar. We meet Kruchkin, a leading figure in Ulaanbaatar’s Russian community, in the wood-panelled bar of the Bayangol Hotel, a shabby socialist-era tower that was for a long time Mongolia’s only hotel. He came to the country in the 1980s to work as an engineer at the massive Erdenet copper mine, the source of 90 per cent of Mongolia’s wealth during socialism. His co-workers included Oleksandr Zelensky, a computer scientist and father of the current Ukrainian president, who brought his young family to live in Mongolia for four years.

“I organised a Mongolian language club and Zelensky’s father visited every week,” says Kruchkin wistfully. “He was smart, a pioneer of Mongolian computation.” Like Kruchkin, Zelensky was one of thousands of Soviet citizens who came to work in Mongolia, a satellite state that was never officially part of the Soviet Union. Both were members of a diaspora that left a legacy viewed mostly favourably today due to its contribution to the country’s culture and economy. But this legacy is being tested by Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Kruchkin describes Ulaanbaatar’s Russians as “divided” over the invasion and, though by no means a dissident himself, he has published a new Russian-Mongolian dictionary to assist those fleeing the fight. Part of the reason why the language barrier is fairly easily surmountable is because Mongolia adopted the Cyrillic alphabet in

1941 after encouragement from Moscow. This, combined with the fact that Buryat and Tuvan Russians share a historical cultural affinity with their Mongolian neighbours, has made the country an attractive destination. Still, after much toing and froing, three Buryat men due to meet Monocle pull out at the last minute citing some vague uncertainty. Are Russians in Mongolia scared of being deported? “Not really,” says Kruchkin. “They usually stay for a month and then go to Thailand or Vietnam.” It seems unlikely that shadowy fsb agents are keeping tabs on their countrymen in Ulaanbaatar. “Mongolia is very open,” says Kruchkin. “Right or wrong – anything goes.” His casual response betrays an astonishing truth: of all the former socialist Central Asian states, Mongolia is the only one that has managed to transition to genuine democracy.

The health of this democracy is apparent in Monocle’s meeting with the prime minister, which is moved several times to accommodate late-night parliamentary debates on constitutional reforms. But it is perhaps most colourfully demonstrated by Mongolia’s rumbustious media culture. The country has a constellation of private news networks vying for its citizens’ eyeballs. And though the state-run Mongolian National Broadcaster initially echoed Moscow’s description of the Ukraine war as a “special military operation”, debates for and against the invasion play out nightly among the country’s coiffed pundits. Their ambivalence is matched by the population at large. Partly this is due to geography. Despite their shared socialist past, Kyiv feels (and is) a long way from Ulaanbaatar. But it’s also due to the largely positive way that Russia is viewed for having hauled Mongolia up from near-feudalism to become an industrialised urban society in the 20th century. And in the 21st century, Russia’s cordial relations with Mongolia could be regarded as one of Putin’s few foreign-policy successes.

In November 2000 the new Russian president became the first of his country’s leaders to visit Mongolia since Leonid Brezhnev in 1974. Three years later, Putin agreed to write off 98 per cent of Mongolia’s Soviet-era debt (about €10.4bn). Then in November 2010 he wrote off another 98 per cent, this time of post-Soviet debt. Coupled with a new visa-free regime, which led to a revival of tourism and trade between the two neighbours, these actions greatly bolstered Russia’s standing in Mongolia. Putin’s charm offensive paid off in September 2019, when he and Mongolia’s then-president, Khaltmaagiin Battulga, signed a treaty that officially upgraded the two countries’ relationship to a “permanent comprehensive strategic partnership”, which included a pledge not to participate in “blocs or military-political alliances” or “any actions or support of such actions” against the other. When he put pen to paper, Battulga probably wasn’t expecting the treaty to be so searchingly tested so soon. Does this document forbid Mongolia from condemning Russia over Ukraine?

“We have expressed our position at the UN that as long as this war goes on it is negatively affecting the whole world,” Oyun-Erdene tells Monocle, without hiding his amusement at the mention of Battulga’s name. The former president is an eccentric mogul and judo obsessive whose close ties with Putin were part of a plan to cultivate a strongman image at home. Battulga’s rise and fall is further proof of Mongolia’s frenetic political system, in which leaders are lucky if they serve their full terms without being wrestled to the mat by an adversary.

Oyun-Erdene, who has a postgraduate diploma from Harvard, is a more sober figure, focused less on flaunting his physical prowess and more on developing his country’s economy. He has written a manifesto entitled Vision 2050, which aims to make Mongolia a developed economy by the middle of the century. “In 2023, our growth is projected to be 7.9 per cent and our GDP per capita has just reached $5,000 [€4,500],” he says proudly. “If you look at the Asian Tigers – Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan – once they reached $10,000 [€9,000] per capita their social problems became more solvable.” Oyun-Erdene has some pressing social problems to deal with too. Rapidly urbanising Mongolia is suffering several urban maladies in extremis.

Take a lift a few storeys above the traffic-choked streets of Ulaanbaatar and you will see that the hills surrounding the city are dotted with tens of thousands of brightly coloured shacks and white tarpaulin-clad yurts. These are the ger districts, the slums named for the yurts that are a symbol of the country’s identity as well as the challenge of raising the prosperity and quality of life for much of the population.

Almost every Mongolian owns a ger (which translates as “home”), whose easy construction and portability are essential to the country’s traditional nomadic way of life. When rural dwellers, often nomads themselves, move to Ulaanbaatar, they bring their families and their gers, pitching up in the hills looking for a better, more sedentary life. These districts, which have swelled to hold more than half of the city’s population, have no sewage system or electricity – every ger contains a coal-burning stove at its centre. For most of Ulaanbaatar’s long, bitterly cold winters, the world’s coldest capital is subsumed in thick black smog.

In one district, monocle meets Chimgee, who lives in a ger with three generations of her family. Its blank exterior gives no clue of the profuse colour – hand-drawn posters, family portraits, piles of toys – within. Like many of her neighbours, Chimgee suffers from chronic bronchitis, a fate she is keen for her grandchildren to avoid. Sometimes the pollution is so bad that she forbids them from going outside. It’s almost summer but Chimgee still gets through at least two bags of coal a week. “All the politicians talk about reducing pollution but nothing ever changes,” she says.

Chimgee is well aware that, along with every one of her fellow ger district dwellers, she is contributing to the pollution problem. But she also knows that Mongolia is a vastly unequal society with a resource-extracting oligarchical elite who get richer while their poorer compatriots choke. Like the pot of salty milk tea that Chimgee has primed for guests, the latter group’s anger occasionally boils over. This was the case in December 2022, when thousands of Mongolians descended on the government palace to protest the theft of billions of dollars of state-owned coal by corrupt officials. Hordes of mostly young people poured into the city’s main Sükhbaatar Square, where they camped out for weeks in temperatures that plumbed minus 30c. A nervous government eventually announced several high-profile suspects (including former president Battulga), at which point the crowd dissolved almost as quickly as it had materialised.

Oyun-Erdene claims that constitutional reform, which will increase the number of MPs in the State Great Khural (Mongolia’s parliament) from 76 to 126, is designed to combat corruption by loosening the grip on the legislature of a small number of party grandees. Some have disputed whether creating more parliamentarians able to be corrupted is the best way to prevent corruption but the prime minister also has a less controversial plan for ensuring that Mongolia’s mineral wealth is shared among its people. “We are in the process of creating a national wealth fund,” he says. “Thirty-three per cent of revenue [from natural resources] will be given to development in three areas: education, health and housing.” Much will depend on whether Oyun-Erdene, himself a scion of the elite, can establish this fund. If not, it’s doubtful his government would survive another bout of unrest such as last winter’s.

For now the prime minister talks up potential solutions to his people’s plight: a metro system or ring road to alleviate Ulaanbaatar’s traffic problem, while diversifying away from burning coal to ameliorate pollution. Despite a push to increase tourism and attract more international film productions to the country, these plans are all dependent on resource extraction that involves, among other unsavoury things, closer ties with Russia.

Last September, in the Siberian city of Vladivostok, Oyun-Erdene and Putin agreed in principle to the construction of a gas pipeline connecting Russia and China through Mongolia. The Power of Siberia 2 (pos2) pipeline would enrich Ulaanbaatar’s coffers by an estimated $1bn (€890m) a year in transit fees and attract thousands of construction and maintenance jobs. Ready access to natural gas could also help to reduce pollution. But critics have argued that the pipeline would leave the country more vulnerable to pressure from its neighbours. Indeed, Ukraine’s status as a transit country for Russian gas to western Europe was often used by Moscow to punish Kyiv.

Undesirable? The prime minister disagrees. “Mongolia has a goal to be a transit country and a corridor between Europe and Asia,” he says. “This pipeline has been part of intense talks since before the situation between Russia and Ukraine.”

Oyun-Erdene refuses to concede that pos2 might make his country vulnerable to coercion. Perhaps he can’t afford to. At the moment, Mongolia is happy to play East and West off against one another, even taking advantage of a deterioration in relations between Australia and China to become the latter’s sole supplier of coal. This tactic has served the country well in the past but is now high-risk as the world potentially splits into factions. Sinophobia has always been used by politicians here during elections but with Beijing stoking tensions in the Taiwan Strait, many Mongolians believe that an expansionist China could have designs on them too. “Mongolians think that after Taiwan, they are next,” says monocle fixer Sukhbaatar. But when asked about Taiwan, Oyun-Erdene is less equivocal than over Ukraine. “Mongolia follows the UN Charter, which says that Taiwan is part of China,” he says. “And Mongolia doesn’t comment on the domestic affairs of other countries.”

It’s a sensitive subject and, as in its relationship with Russia, Beijing holds all the cards. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the importance of China as a buyer of Russian oil and gas has vastly increased. But despite Putin’s desire to sign off on pos2, Beijing is holding up the deal to extract more favourable terms. During a visit to Moscow in March, Chinese premier Xi Jinping refused to discuss the project, even cutting his trip short to avoid it. It’s difficult to imagine Mongolia being the beneficiary of more protracted negotiations over the pipeline.

If the Sino-Russian alliance were to become one half of a new world rift, Mongolia would be even more isolated than before. Oyun-Erdene believes what he describes as a “new Cold War” must be avoided at all costs. “It will go on longer than the first one,” he says. Instead of beefing up their militaries and forming new alliances (such as the Aukus pact between Australia, the UK and the US), developed countries should use the money to help poorer ones, he says. “We should have a mechanism in the UN to control defence spending. People don’t want more weapons and there’s a feeling that leaders are not the great statesmen they were before.” It’s unclear to whom he is referring but Oyun-Erdene sees the Ukraine conflict as a neighbourly spat that has gotten out of hand. “I have compared the situation in Ukraine to a family divorce; should the child follow the father or the mother?” Is the US the mother and Russia the father? He smiles. “The irony is the kid usually follows the mother.”

Unlike Ukraine, Mongolia isn’t desperate to split from its overbearing relatives. In fact, to survive in its modern guise, the country is hoping for reconciliation on a global scale. After all, the next divorce could be even messier.

The decline of nomadic life

Mongolian culture venerates the country’s land and the livestock that sustains its people’s meat- and milk-heavy diet. Until the fall of communism, it is likely that most of the population still lived traditional nomadic lifestyles, raising livestock and moving with the seasons. But in recent years, due to a combination of economic and climatic factors, hundreds of thousands of nomadic families have moved to Ulaanbaatar’s ger districts, the capital’s crowded and polluted slums. As well as exacerbating social problems, this massive internal migration is threatening a way of life that is intrinsic to one of the world’s few remaining nomadic countries.

Mongolia is experiencing the dire consequences of rising global temperatures. Since 1940, the average temperature has risen by more than 2c, leading to a marked increase in the number of extreme summers and winters. During the former, unusually dry weather means that the grass that livestock graze on doesn’t grow, while extreme winters (when temperatures can drop below minus 40c) kill even the most fatted calves. Between 1999 and 2010, extreme weather led to the deaths of more than 20 million livestock and slums in Ulaanbaatar swelled, more than doubling its population.

Outside Erdenet, monocle meets Lkhagvaa, a nomadic herder who lives with his wife, Bolortuya, two daughters and their goats, horses and sheep. Their ger, a wedding gift, is decorated with the totems of nomadism: embroidered portraits of Chinggis Khan – the famous Mongol warlord and nomad – and others featuring the five Mongol “jewel animals”: horse, goat, sheep, camel and yak. Lkhagvaa (pictured) had to move from the east of the country to be nearer to the markets that bought his animals for their wool and meat. To get here he travelled for 30 days on horseback, leading some 100 goats and sheep. It’s certainly a tough life but when asked whether he will follow many of his fellow herders in moving to Ulaanbaatar, he smiles and says: “Why, so I can live in squalor surviving from loan to loan?”

One peaceful Saturday morning in 2018, residents of Hawaii awoke to the text message that many had long feared: “Ballistic missile inbound to Hawaii. Seek immediate shelter. This is not a drill.”

Christine Lonie, a retired naval officer who lives on the island of Oahu, was at the gym. While most islanders were bracing for impact, some putting their children down storm drains, Lonie and her husband, Chris, who is also ex-military, suspected a false alarm. “Still, we decided to shelter in place and mix up mai tais,” she says.

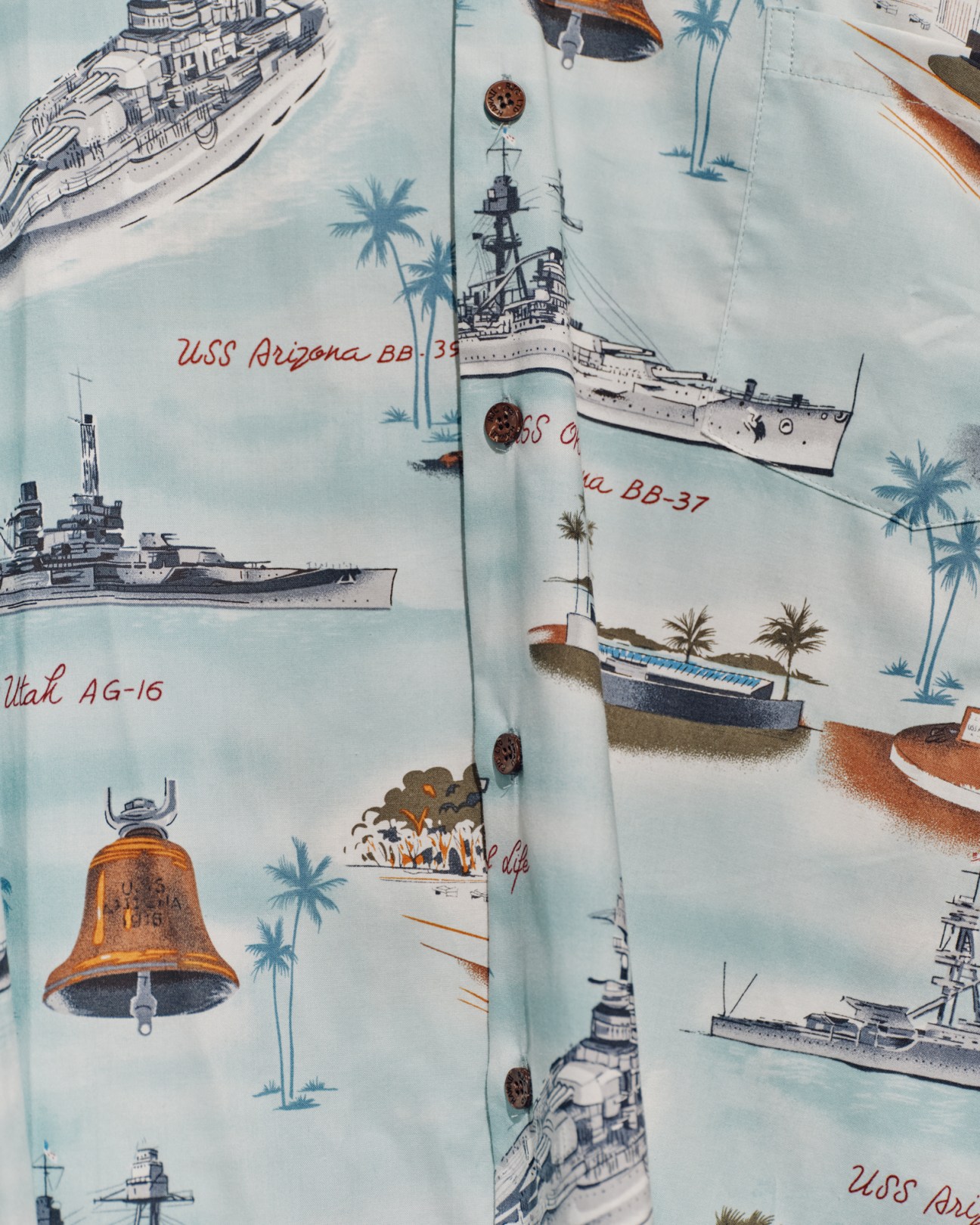

The error, caused by someone clicking “the wrong thing on the computer”, according to authorities, has had a long-term effect on the psyche of Hawaiians. It was a reminder that if a missile were fired at the US from Asia, these islands would be the first in line. “Everyone has the perspective of Pearl Harbor,” says Lonie, referring to the 1941 air attack by Japan that propelled the US into the Second World War.

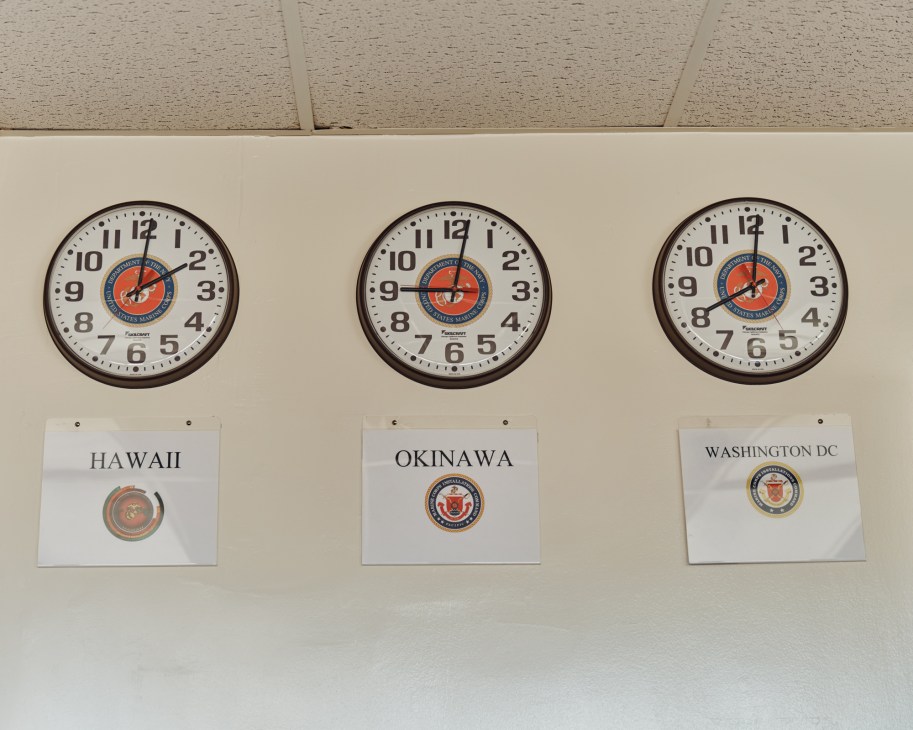

Hawaii is once again a port in a storm. In April, China signed a security deal with the Solomon Islands that could result in Chinese units and ships stationed on the Pacific archipelago, which is closer to Honolulu than Beijing. The most senior US admiral in the region has warned of a new “boldness” about China’s threats towards Taiwan and that the war in Ukraine shows that such an invasion could be possible. Some analysts say that the US has already lost the balance of power in the Pacific. A long-delayed US pivot in strategic focus is under way and the 50th state has renewed its role as a crucial staging post for the military. The Department of Defense administers about 80,000 hectares of Hawaii, representing almost every branch of land and sea warfare. Most sunseekers on a stretch of Waikiki probably don’t realise that they’re laying their towels on military land or that the brutalist balconies of the Hale Koa resort are only for veterans and serving soldiers seeking r&r. Likewise, most are oblivious to the sheer number of bases, which have their own police and shopping malls. The islands of aloha and surfing are also an important training ground for what could be the next theatre of war.

“We are really in the business of deterrence,” says Major General Chris McPhillips, director of strategic planning and policy at the US Indo-Pacific Command (Indopacom), a strategic nerve centre at the top of a hill in Oahu that co-ordinates 375,000 naval and land personnel over a vast area from India to just off the coast of California. Under Indopacom’s direction, the military has embarked on “forward-deploying” thousands of troops across the Pacific. In Darwin, Australia, scores of US Marines are in place; US Army Pacific has stepped up training in the Philippines, Japan and South Korea; and in June, Hawaii will host the Rim of the Pacific exercise, bringing together allies for what is both a joint training drill and a show of force.

McPhillips gives Monocle a whistle-stop tour of China’s nefariousness. “There’s a long-term strategy to create an environment where violations of the rules-based order are normalised,” he says, pointing to spots on a map of the Asia-Pacific region in his office. “Look to India and the line of control where there is armed aggression by the PRC, or east to Vietnam where dams are being built by China and water is being diverted. Every day the pressure on Taiwan is ratcheting up, in terms of ship presence and air incursions.”

McPhillips talks about the “tyranny of distance” – in essence, the problem of how to get US forces across the ocean in the event of a flash outbreak of violence. If China were to suddenly rain down missiles on Taiwan or if US and Chinese ships collided in the South China Sea, which Beijing has peppered with military runways, it could take hours or days simply getting US troops there from far-flung bases.

“What we are trying to do out here is to posture the force across the region so that we are more forward, more of the time,” says McPhillips.

At 07.46, on the other side of Oahu, 24 young US Marines are daubing their faces with camouflage paint beneath a banyan tree. Hawaii’s balmy trade winds don’t penetrate into this thicket of jungle and sweat rolls down the faces of two soldiers carrying rocket launchers, which are filled with sand to simulate being fully loaded.

The squad is in a gruelling three-week scenario that pits them against a Chinese enemy. They will sleep in the open and track their opponents through the undergrowth. Their sergeants say that, unlike in Afghanistan, they will be up against a “pure adversary” of comparable might and preparedness, which is indicative of how much China’s forces have modernised over the past decade.

Occasionally there’s a peal of gunfire in the distance or the shudder of a helicopter overhead. “Everyone thinks that Hawaii is a paradise,” says Staff Sergeant Kevin Cassara, squatting on an ammunition box filled with blanks. “But out here they get biting centipedes and wild hogs.”

For more than 20 years the US Marines served largely as a counterinsurgency force in the Middle East. These 24 soldiers have so far trained mostly in the deserts of California or Australia; the jungle can be bewildering. “The Marine Corps is going back to its amphibious roots,” says Cassara. “We’re shifting to be a light-infantry, island-hopping force – and Hawaii is essential for this. We can mirror what they’ll face in the South China Sea.”

The platoon halts at the side of a dirt road. Corporal Stefan Murillo kneels beside his gunner, who is lying prone with his weapon trained on a gap in the foliage. “We’ll set an ambush and wait for the enemy to come by,” says Murillo, whispering and sniffing back sweat. “The next wars might take place on islands just off China – hot, humid places like this. So it’s about getting Marines ready for this kind of climate, this vegetation, so that they are more lethal.”

Would the US directly intervene if China invaded Taiwan? Indopacom will not say. Australia’s former prime minister Kevin Rudd argues in his book The Avoidable War that the lack of clear consequences if such red lines are crossed, agreed between the US and China, only raises the risk of a confrontation. “Since 2017, Washington has increasingly come to believe that a Chinese military takeover of Taiwan – and especially one that the US did not resist – would effectively be the end of the US-led rules-based order in Asia and perhaps the world,” Rudd tells Monocle.

In Hawaii, the pivot to the Pacific that Barack Obama’s administration announced a decade ago is now happening in earnest. At Bellows Beach on Oahu, Marines are being taught how to drive new light tactical vehicles rather than the armoured Humvees employed in Iraq. (At one point a staff sergeant has to usher a few errant sun worshippers from the sand.) And on the flight line at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, crew members are testing the MV-22 Osprey; part helicopter, part plane, it can land vertically and is superceding the Cobra and Huey attack helicopters that were a mainstay of Marines operations.

“The threat isn’t always the enemy – it can be logistical supply lines and the Osprey can be a connector,” says Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Blumenfeld. “As the situation deteriorates in the region, being able to rely on our allies and relationships will be paramount.”

The US has traditionally relied on friendly atolls and archipelago nations to island-hop its forces across the Pacific. China’s deal with the Solomon Islands, which have been a US thoroughfare since the Second World War, has everyone spooked because it shows that Beijing is now seeking to do the same. While the US hunkered down in Iraq and Afghanistan, then navel-gazed about what role it should play in the world, China handed out grants and loans in strategic outposts around Asia-Pacific, reaching a peak of $287m (€272m) in 2016, according to Australia’s Lowy Institute. In Vanuatu, it has paid for a port expansion that many fear could be turned to military use. It has curried favour in Fiji, Kiribati and Papua New Guinea, and is accused of funding infrastructure to ensnare developing countries in a debt trap. Beijing has said that its investments are welcomed in the Pacific, while the prime minister of the Solomons has hit back at criticism of the deal, saying that his country can manage its own sovereign affairs.

“I’m concerned that, left unchecked, many of the countries in the region will fall prey to the Chinese,” says Major General McPhillips. “That is an authoritarian, dictatorial and closed society.”

It is all a question of resolve and whether the US and the West are truly committed to competing with China in the Pacific. The US will open a new embassy on the Solomon Islands after years without one. At Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Naval Fleet Band is tuning up for a grand summer tour, taking in Palau, Vietnam and the Philippines, among others, as they accompany the USNS Mercy on its medical aid mission through the region. “We’ll hit strategic countries where we want to maintain relationships,” says the band’s leader, Lieutenant Luslaida Barbosa.

There’s certainly a new sense of focus but the US’s allies wonder whether it will last while war rages in Europe. At Fort Shafter, the “Pineapple Pentagon” and the oldest US military outpost outside North America, US Army Pacific General Charles Flynn (brother of Michael Flynn, who was briefly Donald Trump’s national security adviser) is just back from a five-nation tour. “In the questions being asked by think tanks, policymakers and military leaders, the undertone was, ‘Are you committed out here?’ My response was, ‘Absolutely, and there’s plenty of work for all of us.'”

Others aren’t so sure. “The line that I’m getting from US government officials is, ‘We’ll just deal with Ukraine and then we’ll get back on track with China,'” says Oriana Skylar Mastro, a fellow at Stanford and the American Enterprise Institute, who has advised the US military on strategy and speaks to us in a civilian capacity. “But we are already behind the curve on our ability to compete militarily with China.” For the past 20 years, says Mastro, the forces at Indopacom’s disposal have been significantly less than what it was assigned. McPhillips’s team will not say how many forces are “ready to go”.

Numbers do count, says Thomas Fargo, former admiral and commander of Indopacom. “We still field the finest ships and aircraft, and the quality of our people is second to none,” he tells Monocle in his office in Honolulu. “If you look at the force we have in the western Pacific, it is no greater than it was 30 years ago, whereas the Chinese order of battle has gone up by a factor of three to five.”

Hawaii’s importance is expected to grow in the years ahead and the US Department of Defense must keep Hawaiians on board about sharing their islands with so many soldiers. Last year military families on Oahu found that their tap water had a whiff of petrol: a historic naval fuel reserve called Red Hill had leaked into the supply.

“This was the boiling point for the relationship,” says Esther Kia’aina, vice-chair of Honolulu City Council, who has campaigned for greater land rights for Native Hawaiians. The Pentagon has since said that Red Hill will be closed. “If they hadn’t taken us seriously, you would see a whittling away of the overall military operations in Hawaii,” she says, referring to renegotiations in 2029 for several key leases of military land.

There is no greater mark of this fractious co-existence than Pearl Harbor. Prior to the pandemic, 1.8 million tourists a year visited the site and yet it’s still an active military base housing Indopacom’s war-gaming centre. (By most accounts, the US keeps losing when it plays out a Chinese takeover of Taiwan, though the military says that finding failures is the point of the exercise.)

Pearl Harbor’s importance in the national story of the US can’t be underestimated. For some, it’s a potent symbol today of how a war in Europe that is left to fester – a prolonged disturbance of the rules-based order – can eventually come knocking at the US’s door.

“What happened in the Second World War was that a couple of powers weren’t receiving any resistance and, almost too late, the Western world rose up and challenged them,” says James Neuman, a naval reservist who leads tours to the memorial of the USS Arizona, a battleship that sank with 1,102 men onboard. “This is a reminder that America can’t be in isolation as a country,” adds Neuman, peering into the sunlit harbour where the hull of the Arizona can be glimpsed on the seabed. “We need to be vigilant and prepared at any time to stand up for our values.”

In his sea-facing reception room in downtown Kingston, Jamaica, Michael Lodge is running out of space. As secretary-general of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), Lodge receives diplomatic gifts from all over the world: a commemorative plaque from Mauritius, tapestries from China, Tongan woodcuts. There are so many trinkets that they’ve now filled the shelves and are lining the corridors.

It’s not surprising. The organisation Lodge heads up grants contracts to nations to explore and, some day, extract the wealth of precious metals found in the seabed in international waters. It is perhaps the most important multilateral body that almost no one has heard of.

Deep-sea mining – exploration at a depth of 200 metres or more – is currently forbidden until a set of regulations for the industry can be agreed on by the 167 member states, and the EU, who send representatives to the ISA. They’ve been at it for 30 years. But in July 2021, tiny island nation Nauru fired the starting gun: it informed members that it would apply for a contract to extract metals from a patch of seabed in the eastern Pacific. This in turn triggered a clause inscribed in the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea, which means that negotiations on the rules for deep-sea mining, so as to assess Nauru’s application, must be finalised within two years.

The next meeting of ISA member states is in August and the representatives have entrenched differences to unpick; the pressure is on to find agreement by summer 2023. If there’s a glisten on Lodge’s brow, then it’s probably not just the mid-morning sun filtering in between the blinds.

“You know, we’re not all coming to Jamaica just to go to the beach and to continue discussing something that will never happen,” says Lodge, a Brit who doesn’t mince his words. “In a way, that clause is doing us a favour; it’s concentrating minds.” One thing that irks the team at the ISA is the line that we know more about the surface of the moon than the deepest parts of the ocean. No doubt the deepest seabeds are among the world’s last great untouched wildernesses, where almost every expedition uncovers new species and new facets of life at extreme depths. But, Lodge and his colleagues say, we know much more about the deep than is commonly thought – and that knowledge is accelerating quicker than ever before.

There are vast fields of so-called polymetallic nodules – tightly compacted clumps of copper, nickel, manganese and cobalt, fused over millions of years – that form like cobbles in the seabed. These rare metals are crucial for making the batteries that go into electric cars and smartphones, and have been found at a sunless, otherworldly depth of several kilometres called, rather poetically, the abyssal plains. The majority of the world’s cobalt currently comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is rife with child labour scandals and reports of environmental catastrophe.

“Consumers were horrified to learn that their Teslas or their iPhones could potentially have had this cobalt in it,” says Corey McLachlan, head of stakeholder engagement at The Metals Company, a Canadian start-up that has partnered with the Nauru government. His company has designed a mollusc-shaped vehicle capable of sucking nodules off the seabed, and touts its method as a less wasteful, less polluting alternative to any mining that happens on land. In September, a union of environmental campaigners demanded a moratorium on future deep-sea mining, noting the Nauru case and arguing that we don’t know anywhere near enough about the ecosystem of the seabed to start hoovering it. The concern is particularly about the plumes of sediment it will kick up. BMW, Google, and Samsung have all added their voices to the call. McLachlan counters that this industry, unlike any other, is being tightly regulated before any activity has ever taken place: “If we’re going to get to a zero- or low-carbon world, it’ll require a significant injection of new metals,” he says.

Mining the seabed is expensive – a fact that has stymied the industry in the past. But the growing demand for electric vehicles has the potential to spur a gold rush. The job of the ISA, then, is to prevent a destructive scramble for resources. Founded in 1982, the ISA was modelled on a consensus system like a mini-UN: representatives of 167 countries and the EU gather in Kingston every year (the US never signed up but sends observers) to work out how to manage deep-sea mining outside national jurisdictions, while ensuring that it doesn’t cost us the Earth.

“I don’t report to António Guterres,” says Lodge, as we pass a photograph of him with the current secretary-general of the UN. Indeed, the ISA was established as a wholly autonomous body, mandated under the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea, the rules governing the use of all oceans and their resources.

“The negotiators [of the convention] had a vision for what was needed so that these minerals do not become a source of war or political instability, at a global scale,” says Marie Bourrel-McKinnon, a French expert on the legalities of the ocean and Lodge’s senior policy advisor. “There was an understanding that if we want to live together, we will need to agree on a regime for deep-sea mining that would one day come alive.”

That day may be closer than we think. The ISA’s 50-strong team, representing 20 nationalities in all, are working flat out ahead of the next meeting. Japanese researcher Kioshi Mishiro is just back from seven weeks on a boat in the eastern Pacific, crunching vast amounts of raw data gleaned from the abyss. He enthuses about the importance of the work, “although I did spend the first week totally seasick,” he says with a smile.

Ulrich Schwarz-Schampera holds up a two million-year-old shark’s tooth encrusted with precious metals. “You get a completely different view of light down there,” says the German geologist about his deepest 1,500 metre dive. “Especially with the bioluminescence; you see nothing for miles and then – pow! – a creature flashes and disappears into the darkness.”

We’re taken around the ISA’s well-thumbed library of ocean law, and its fastidiously-kept records of every meeting in Kingston since 1994. “It’s good that we’re the ones bringing everyone together to get the job done,” says Jamaican administrative assistant Camelia Campbell. Her colleague and compatriot Sheldon Carter agrees. “It gives me a lot of pride that this is the host country,” he says.

How the ISA ended up in Kingston goes to the core of its mission. According to Lodge, the UN wanted global institutions outside of the typical diplomatic centres of London, New York and Geneva; Fiji and Malta were also contenders. Even the tropical modernism of the conference hall, purpose-built in 1982 by a Jamaican architect, harks back to an age of confidence, with locally-woven baskets in the ceiling for acoustics and vast windows that allow light to pour in off the Caribbean Sea outside.

In the same spirit, the Law of the Sea states that international waters and their mineral wealth belong to no one – it is the “common heritage of mankind”. This means that any seabed spoils must be distributed between all nations; rich and poor, landlocked or maritime.

That principled stance, however, has become a sticking point. Economists at MIT have been trying to work out how the considerable bounty from deep-sea mining could be divvied up fairly. Previous efforts to find an equation have come up with trivial if equitable amounts, or had countries with vast populations, such as India, taking the lion’s share. Another option, says Lodge, is to set up a sovereign wealth fund for the ocean “to generate more scientific knowledge, to fund international exploration and development projects that would assist least-developed countries”.

Every application to explore for minerals must include a provision of seabed reserved for developing nations. Many small island states with limited resources, such as Nauru, regard this industry as one they might call their own. “We have actually just now started sponsoring exploration,” says Alison Stone Roofe, Jamaica’s permanent representative to the ISA, who came to the post after being her country’s first ambassador to Brazil. Jamaica has partnered with a UK-Danish firm, Blue Minerals Jamaica Ltd, to explore for nodules in the eastern Pacific; Tonga, Kiribati and the Cook Islands have their own sponsorship deals.

“I’m very confident that the next few years will be progressive,” she says, referring to the revved-up pace of negotiations at the ISA. “We don’t want it rushed. It needs to be rule-driven and with regulations that make sense and really contribute to the protection of the marine environment.”

The clock is ticking. If negotiations aren’t finalised by next July, then Nauru’s application to begin mining would be considered according to what’s been agreed so far – even if the regulations are still in the draft stage. A number of ISA member states have criticised the fast-tracked talks, while conservationists insist that it’ll rush through rules at the expense of our oceans. Marie Bourrel-McKinnon at the ISA believes that we should have faith in countries’ sense of responsibility. “Trust the governance,” she says. “Trust the fact that multilateralism has been able to save us and protect us for more than 70 years. This is the only way for us as human beings to live together.”

Yet this optimism sounds like a throwback to a more collegial age, when the world had more faith in multilateral bodies and the rules-based order, which nowadays seems permanently on its sickbed. If deep-sea mining proves to be workable and lucrative, what is there to stop powerful or belligerent powers from going down to the most obscure parts of the ocean and taking its riches for themselves? Lodge scoffs at the question. “Who is going to do that, knowing that this is contrary to international law – a rogue state, North Korea? It doesn’t make sense.”

There may be, in Lodge’s office, a ceremonial plate in cyrillic and a Chinese-made model of a fish-shaped submarine but it’s not too hard to think of a situation in which a country has run roughshod over UN rules.

“You need to operate within the regime,” says Lodge. “It’s just such a difficult enterprise to take part in. This needs a high level of investment [and] co-operation.”

Perhaps it’s the vastness of scale in which the ISA operates – the great blue beyond all borders – which gives this sense of perspective. As we walk down to Kingston’s waterfront for photographs, Lodge tries to explain one of the great misconceptions about deep-sea mining.

“People think it’s working just out here,” he says, pointing to the calm natural harbour in front of Port Royal. “But no.” Lodge pauses, shielding his eyes and gazing into the hazy, choppy horizon. “It’s sailing for eight days – into all that.”