We are living at a moment when the only thing that’s predictable is the unpredictable. Unforeseen events come hurtling towards us from every angle, each with the potential to rattle the world order. Russia’s war in Ukraine, the fall of Bashar al-Assad in Syria and South Korea’s constitutional crisis all happened when most people were looking the other way. And these tectonic shifts have the potential to affect so much more than state relations; they also shape global trade, how we travel, the culture that we consume and even how confident people feel when they get up in the morning.

To help Monocle readers move through any potentially choppy waters, we have appointed a new security correspondent who joins the magazine and Monocle Radio from this issue. Gorana Grgic, who is also a senior researcher with the Swiss Euro-Atlantic Security team at eth Zürich’s Center for Security Studies, opens this month’s Agenda section by unpacking all of the forces at play right now and arguing that, “only by staying informed, anticipating change and finding ways to adapt and respond can we navigate the uncertainties ahead and hopefully contribute to shaping a more secure future”.

You’ll also be hearing more from Grgic, and other new and established Monocle voices, in the coming months at monocle.com. Because while these might be interesting times, Monocle has a host of important projects for the company in play and a key one of these will be the launch of an enhanced digital experience. I won’t give too much away now but delivering our common sense, solutions-driven view on everything from urban design to social change will be central to our plans.

There’s some other house news to share. As you will have read in these pages, Monocle opened its first office in Paris last year and now we are on the cusp of revealing a new shop and café space in the city (and we are already moving to a new, larger office too). One of the many benefits of having a growing team in the city is that it helps to shape the whole tone of the company. From the beginning we have always strived to be a global brand rooted in Europe. Now, with HQs in Zürich and London and a sizeable presence in Paris, that’s easier than ever.

Reading the page proofs for the February 2025 issue – with stories from all over the world, not just France – I was struck again and again by the number of people who see a problem and step forward with a solution; by the range of civic and business leaders, designers and architects who refuse to accept just a mediocre solution, who insist on setting improved benchmarks. That’s why we hope that this issue will give everyone hope and an injection of ambition as we dive into 2025.

A prime example of this is the University Children’s Hospital Zürich by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. The building makes extensive use of timber, embraces nature and strives to put children first in all its planning decisions. As our story says, it creates “a place for treatment but a sanctuary for children, their families and staff. The building feels like a warm embrace – a hospital that saves lives while improving people’s life quality.” It’s remarkable.

That same determination to come together to affect meaningful change is also evident in our report on how Kansas City revived its downtown. Back in the early 2000s, about 13,000 people lived in the heart of the city; now, according to the city council, more than 122,000 people work in the greater downtown area and office occupancy is at 86 per cent. And among the elements that helped to change the narrative were good urban-planning decisions that were citizen-led.

Elsewhere in the issue you’ll discover how an emblem of African optimism has been revived in Addis Ababa, why a spate of museum offerings shows how we can still come together because of art and storytelling, and why you should keep using a pen and paper every so often if you want to maintain a healthy brain (this letter might be handwritten next issue). Enjoy.

If you want to stay ahead on all of Monocle’s news and views, make sure that you’re subscribed to our newsletters, The Monocle Minute and Weekend Editions. And if you have any ideas and solutions that you’d like to share, or have feedback to give, remember you can always contact me at at@monocle.com. —

The world is filled with buildings erected primarily as symbols. Some are impressive; others are not. When Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia inaugurated Addis Ababa’s Africa Hall in 1961, it hit the sweet spot between symbolism, functionality and form. Designed by Italian architect Arturo Mezzèdimi, the HQ of the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), whose mandate is to promote the economic and social development of its member states, became a beacon of architectural modernity for an entire continent, while heralding the transformation of Addis Ababa from, in the emperor’s words, a “great village” into a “truly great capital”, and acting as a lodestar for African political co-operation. That’s why the brief for the building’s renovation, issued in time for its 50th anniversary in 2011, was weighted with historical expectation; and why its subsequent transformation has lent it renewed symbolic value.

In 2013 the commission for the work was awarded to a Brisbane-based team from Architectus Conrad Gargett. “It was a first for us to work in Africa,” project architect Simon Boundy tells Monocle. “But the UN being an equal-opportunity employer, we established that we were the most qualified and experienced for the job.”

One of the first things that the firm did was hire Mewded Wolde, a fresh-faced architecture graduate from Addis Ababa, to be its point person on the ground. It then asked her to provide accurate measurements in order to build a scale model of the building. “Eleven years ago, we didn’t have all of the modelling software that we have today,” says Boundy. “A few years later, when we got a 3D-scanning machine, we overlaid our scan onto the model and it was remarkably accurate.” Accuracy became Architectus Conrad Gargett’s watchword. The hardest thing about renovating a protected building is the lack of freedom to make major alterations – a restriction compounded by the 21st century’s near-exhaustive list of health and safety regulations. “If you’re a heritage architect, you want to preserve and conserve the building,” says Boundy. “But on the other hand, you have still got to modernise it and keep it relevant by making it accessible and safe. Otherwise, it doesn’t get used.”

Africa Hall in numbers

Year completed:

1961

Original construction time:

18 months

Overall area:

75,000 sq m

Re-inaugurated:

October 2024

Size of ‘Total Liberation of Africa’, a stained-glass artwork by Afewerk Tekle:

150 sq m

Number of bespoke original furniture pieces created by Arturo Mezzèdimi:

500

Number of new mosaic tiles fabricated to replace the deteriorating façade:

13,000,000

When the building’s horseshoe-shaped plenary hall was built, 26 African countries were represented in the ECA. By 2011 this number had risen to 54. As a result, Mezzèdimi’s original wooden seating had to be sacrificed. “We designed new joinery using these old architectural drawings,” says Boundy. “This meant that we were able to make something contemporary that could house audiovisual conferencing and voting systems, while also ticking the box for accessibility.”

Any additional box-ticking was concerned with preserving the space as much as possible, even if that required painstakingly producing like-for-like replacements of features that were deteriorating. The mosaic tiles on the exterior of the building had to be removed to address structural degradation, so 13 million new ones were fabricated using the original ceramic material and replicating their textured profile and brown, orange and off-white colour scheme. The building’s entire façade was then reglazed to improve its energy efficiency and structural integrity, while the landscape garden, and its fountains, garden beds and integrated stairs, were completely refreshed and reinstalled.

But the jewels in the building’s crown are its integrated artworks. The most famous of these is the 150 sq m stained-glass triptych “Total Liberation of Africa” by Ethiopian artist Afewerk Tekle. The dazzling work, which features scenes from the continent’s history, was made by Studio Atelier Thomas Vitraux in Valence, France. Architectus Conrad Gargett enlisted Emmanuel Thomas, the grandson of the original maker, to restore it.

A mosaic artwork depicting fearsome African fauna, which was removed soon after the building was opened, was also recreated using archival drawings and photographs. Meanwhile, 500 pieces of bespoke modernist furniture, designed by Mezzèdimi, were spruced up and returned to their intended positions. “From the cafeteria to the rotunda, every space had a designed furniture piece and a specific colour palette,” says Wolde. “It’s very difficult to find a building these days with integrated artwork, let alone on this scale.”

It would not be hyperbolic to describe this building as the crucible of 20th-century African integration. Two years after its inauguration, the leaders of 33 states across the continent signed the Charter for the Organisation of African Unity (oau), while basking in the polychrome splendour of Tekle’s stained-glass window. The oau was the precursor to the African Union, which is also headquartered in Addis Ababa. Among the latter’s founding principles is a pledge to promote “unity, solidarity, cohesion and co-operation” among African countries. Such sentiment was born in the heady days of decolonisation, when nations pulsed with the optimism of splendid autonomy that Africa Hall represented. Unfortunately, much of the hope that powered the building’s construction has been tempered through the continuation of seemingly interminable strife across the continent, not least in Ethiopia, which continues to suffer from the aftermath of a bloody civil war in its Tigray province.

But Wolde believes that Africa Hall’s refurbished state, unveiled in October 2024, augurs some sunshine on the road ahead. “This building will be a symbol of what renovation can bring back to life – how we can look back at our history and reimagine our future,” she says. As symbolic buildings go, it doesn’t get much more potent than that. —

Three other unsung HQs

1.

International Seabed Authority

Kingston, Jamaica

The vast windows of this tropical modernist edifice gaze out on the sparkling Caribbean Sea. Its occupants moved here in 1994; since then, the importance of the intergovernmental body has grown, especially in recent years as deep-sea mining has become a hot topic across the globe.

2.

Interpol

Lyon, France

Since French president François Mitterand inaugurated this glassy postmodern HQ in 1989, the membership of the world’s largest international police organisation has grown from 150 to 194 countries.

3.

Palace of Nations

Geneva, Switzerland

Inaugurated in 1938 to house the League of Nations, this dazzling neoclassical building is now home to the United Nations Office at Geneva, where an array of the organisation’s agencies regularly meet. Among its many splendid spaces is the 754-seat Human Rights and Alliance of Civilizations Room, which features a ceiling sculpture by Spanish artist Miquel Barceló.

“I’m originally from Los Angeles but the answer wasn’t there for me,” says Brian Kim, who runs a string of successful coffee shops in Kansas City. Kim has called the Midwestern metropolis home for more than 10 years. He tells Monocle that he chose to base himself here because it offered him “breathing room” to get his ideas off the ground. “That’s partly down to the cheaper cost of running a business,” he says. “People here also have a lot of enthusiasm for local things.”

Kansas City sits almost perfectly in the middle of the US, straddling the Missouri-Kansas state line. For a long time it had an unenviable reputation. During the mid-20th century, its downtown became a place that was almost exclusively for doing business and residents were gradually edged out to the suburbs. The city centre became a drive-in, drive-out area where the car reigned supreme; by the early 2000s, the downtown population had dwindled to a mere 13,000.

Over the past 20 years, however, there has been a steady reversal of Kansas City’s fortunes. Today it has one of the fastest-growing city economies and downtown populations in the country, and is being talked about as a model of urban renewal. According to the city council, more than 122,000 people now work in the greater downtown area and office occupancy is at about 85 per cent. This compares to a nationwide average across major metropolitan areas of about 50 per cent. At a time when even the great coastal cities are facing the existential threats of desolate office blocks and crime-blighted downtowns, Kansas City can offer a few pointers.

Things began to change when the state government and private investors decided to invest more in the city’s downtown and its housing stock. Since 2002 it has poured more than $10bn (€9.8bn) into the central business district and many of those moving to Kansas City end up living and working in the centre, which boasts the largest residential population of any Midwestern city. Over the past two decades, more than 50 office buildings have been converted into roomy apartments, showing that this can be done successfully, while former industrial areas such as the Crossroads district have had many of their 20th-century brick warehouses transformed into mixed-use developments comprising housing, creative offices and independent shops, bars and restaurants. Meanwhile, the light-rail streetcar system, launched in 2016, is being expanded and is scheduled for completion later this year.

Why the Paris of the Plains is back

The simple principles that turned around Missouri’s biggest city.

1.

Invest in downtown

Kansas City leaders poured money into upgrading the housing and commercial stock in the cbd and were unafraid to turn unused offices into spacious apartments.

2.

Keep historic, family-run businesses close to home

Historic department stores such as Halls have remained part of the fabric of downtown, taking advantage of a growing footfall.

3.

Get people moving

Investments in a new light-rail network in 2016 have paid off, with people getting out of their cars.

4.

Make old buildings work harder

The revitalisation has been guided by the idea of “reuse and restore”.

5.

Put those who live there in the driving seat

Some of Kansas City’s best ideas came from citizen-led initiatives, from enticing entrepreneurs to set up shop to making the city centre more liveable.

Raven Space Systems, a start-up based in the central West Bottoms neighbourhood, is developing capsules that can be used to shuttle cargo back from space and has won contracts from Nasa and the US Air Force, among others. Its co-founder Blake Herren recently secured millions of dollars in funding and was lured to Missouri from Oklahoma by an initiative that provides financial support, office space and mentorship to early-stage technology entrepreneurs for a year if they move to Kansas City. The scheme is run by the Downtown Council of Kansas City, a private, nonprofit body that has driven much of the change here in recent decades. “It’s about making the city a place where people feel welcome to come and try out ideas,” says Tommy Wilson, who oversees the programme. The citizen-led group’s “Imagine Downtown KC 2030” blueprint involves creating more green spaces and enhancing the urban core’s public transport and walkability. “We’re Kansas City residents ourselves,” says Wilson. “It’s far easier to be motivated when it’s your home that you’re improving.”

As a historic crossroads for agriculture, Kansas City has a long history of affluence that’s reflected in the skyline. Rows of art-deco brick buildings were erected during the boom years of the 1920s and 1930s, when the city became known as the “Paris of the Plains” due to its profusion of contemporary architecture and riotous jazz scene. These buildings have been given a new lease of life as shops, a gallery, a wine bar and a brewery. Kyle Evans runs Penrose, a hole-in-the-wall espresso spot. “I left Kansas City in 2013 but, after almost 10 years living in the Bay Area, I decided that it was time to come home,” he says. “When I got back here, I wanted to drink good coffee but also do something meaningful.”

Once one of the world’s largest cattle- trading hubs, the West Bottoms district is now known for a range of trades. Inside a modernist building is Kem Studio, an industrial design and architecture firm. “This is a city that takes design seriously,” says Jonathon Kemnitzer, who co-founded the studio in 2004 with Brad Satterwhite. He tells Monocle that they considered basing themselves in a larger city but Kansas City won out. “It’s so easy to meet with civic leaders here and make things happen,” he says. The studio’s team is now revitalising swaths of land on the banks of the Missouri river. “More than ever, there’s a sense that it’s empowering to be in the Midwest,” says Satterwhite. “There’s space to think here, as well as land to develop.” —

An industrial estate in the east of Berlin is not a place one would expect to see a penguin. Yet visitors to the headquarters of technology company EvoLogics are greeted by one on a shelf. Another is swimming in an outdoor pool. Unlike their Antarctic relatives, these creatures have propellers instead of feet and, instead of fish, cameras, sonar systems and acoustic modems in their bellies. “We don’t copy a penguin just because it’s cute,” Fabian Bannasch, CEO of EvoLogics, tells Monocle. “We take the best ideas of biology and transfer them to technology.”

Since first presenting its penguin-shaped Quadroin in 2021, the company has scrambled to meet demand for these autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). EvoLogics moved into new purpose-built, four-storey headquarters less than two years ago but it is already at capacity; a second building is under construction next door. Over four years, the workforce – mostly electronics developers, robotics engineers and AI programmers – has quadrupled to 125 people. When Monocle visits, there is a nervous hubbub as staff race to complete an German-funded order of 50 Quadroins, set to start patrolling the coastal waters of Ukraine soon.

EvoLogics was founded in 2000 by Fabian’s father, Rudolf, a marine biologist who worked in the department of bionics at the Technical University of Berlin. The scientist had studied penguins in Antarctica, noting that the chubby waddlers were also high-performance divers. “Their shape has been optimised over millions of years of evolution in Antarctic waters,” says Fabian, who took over as CEO four years ago.

However, EvoLogics’ first invention was an imitation of another expert animal swimmer: the dolphin. Rudolf patented an acoustic technology that mimicked the frequencies of dolphin song to enable clearer and faster signalling underwater.

Modems built by EvoLogics are now installed around the world to monitor underwater infrastructure, including oil and gas fields, and offshore wind farms. But the firm always experimented with robotics on the side, developing the Sonobot, a type of waterborne drone, as well as a life-size (and lifelike) manta-ray AUV. The idea for the penguin came about when an oceanographer came to EvoLogics with a problem. To study ocean eddies – quickly shifting vortices that are key to understanding the climate – he needed fast, nimble AUVs that could gather data.

The EvoLogics engineers turned to Rudolf’s Antarctica field notes and built a sensor-packed robot inspired by the swimming mechanics of an Adelie penguin. The Quadroin could swim in groups of six and collect data on water temperature, salinity and oxygen levels. The team realised that the biomimetic design could outperform typical vehicles for a host of applications. “With a traditional AUV, you put it in the water and it’s gone for four hours on a programmed mission,” says Bannasch. “Then you collect it with a crane, plug it into an ethernet cable, run the post-processing, and find out where the Russian [ship] was eight hours ago.” A Quadroin, meanwhile, can be tossed overboard and swim at speeds of 10 knots (18.5km/h) to depths of 150 metres, while communicating in real time with its operator.

EvoLogics serves three main sectors, all of which are booming. “Mankind is still starting to explore what it can do with our oceans,” says Bannasch. Interested parties include scientists working to map a changing climate; commercial entities, including fossil-fuel and renewable-energy companies (as well as the new and controversial deep-sea mining industry); and authorities ranging from police forces for missing persons to the naval forces of Nato countries. To meet a surge in demand from the defence sector, EvoLogics teamed up with Bremen-based contractor Euroatlas to launch the larger penguin-shaped Greyshark, specifically geared towards military use. The 2.5-tonne auv can be sent on month-long missions – to spy on an enemy harbour, for instance.

While penguin AUVs are an easy sell, a question remains: what about the animals that served as their models? Studies have shown that dolphins are bothered by their increasingly noisy ocean habitats, while the Quadroin’s communication system makes it sound like a real penguin. Bannasch is reassuring. “If anything, our vehicles cause less disturbance underwater than other vessels,” he says. “But yes, dolphins frequently come around for a chat. Once they realise that our vehicles can’t respond in their language, they give up.” It’s a good thing that robo-penguins are getting a warm welcome, because it looks as though many more will soon be patrolling the cold seas. — evologics.com

To witness a prime example of how corporate giants can meaningfully insert themselves into the life of a city without plastering their branding all over the place, make your way to Tokyo’s Ginza district. If you’ve visited at any time over the past eight years, you might have observed the transformation of one of its most prominent corners, Sukiyabashi Crossing, once the most expensive piece of real estate in the city. First came the demolition in 2017 of the Sony Building, a towering slice of futurism that originally had 2,300 cathode-ray tubes on its façade. Built in 1966 by architect Yoshinobu Ashihara, the then state-of-the-art structure defined the vision of its creator, Sony co-founder Akio Morita, and announced the ambition of one of Japan’s greatest brands.

Once the old building had gone, Sony turned the blank space into a temporary site for events and pop-ups, as well as somewhere to take a breather. With its lush plants, it was an arresting sight that drew eight and a half million people over three years. Now a new landmark has emerged: Ginza Sony Park, an intriguing hunk of raw concrete open to the street and the elements.

“The previous Sony Building was a showcase for electronics,” says Sony Enterprise president Daisuke Nagano, who has overseen the process. “But our business is now more diversified – music, movies, games, electronics. The challenge was to create something that matched where we are now.” In recent years the streets of Ginza have become a forest of high-rise towers designed for global luxury brands by the world’s finest architects. Ginza Sony Park is different: about half the height of its neighbours and with almost no branding. Nagano didn’t have to worry about the usual commercial pressures – there are no tenants – and the design was a team effort rather than the work of one famous architect. “People remember the Walkman, not who designed it,” he says. “That’s very Sony.”

The structure is not a conventional showroom and has no offices. It’s a free public space that will be a platform for exhibitions, music and ideas. “The building is not meant to be a big showpiece,” says Nagano. “It’s more like a smartphone, which depends on the apps that are added.” The team also thought hard about the meaning of a park. “We felt that it should be considered basic infrastructure, like a bridge or a highway, and we wanted the materials – raw concrete and steel – to reflect that.” The building is open to the street above ground and connects to the subway and underground car park below below. Fragments of the Sony Building have been retained in the underground entrance as a reminder of the site’s past life.

Ginza Sony Park gives back to the Tokyo public the tradition of wandering around the Ginza district and echoes the staggered-petal design of the old Sony Building as it spirals down, allowing visitors a vertical stroll from top to bottom. It isn’t sealed off from the world: the central stairwell is uncovered, so when it rains, you can feel it. It also enjoys the shakkei (borrowed scenery) of Renzo Piano’s remarkable glass-brick building for Hermès next door and has an open rooftop with a bird’s-eye view of the district.

Construction was completed last summer and the pre-opening phase featured Art in the Park, an exhibition of new works by three Japanese artists. Nagano sees potential for the building to be used for social messaging too – the chunky exterior metal grid has already exhibited giant images of endangered animals. Following the grand opening on 26 January, the first event is the Sony Park Exhibition 2025, designed to show six core Sony themes via interactive installations that reference everything from music and gaming to cinema.

Japanese corporations have a long history of cultural engagement but these endeavours are increasingly under pressure from bossy shareholders who seem to know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Where, they ask, is the return on an art museum? Ginza Sony Park shows that there doesn’t have to be a quantifiable financial return but, as an exercise in showing Sony as an innovative creative force, it works on its own terms.

In its own way, Ginza Sony Park is as radical as its 1966 predecessor and sets out the company’s mission in the 21st century to be collaborative and open to ideas. Nagano hopes that it will inspire Sony’s creatives too. — sonypark.com

Australian cities don’t have panoramic piazzas like in Italy, nor do their streets rival the grandeur of France’s finest boulevards. But the treatment of laneways here contains lessons that any municipality can learn from. For the better part of 30 years, players from both the private and public sector have been turning the country’s small-scale thoroughfares into vibrant urban places.

So what is the appeal of investing in such spaces? These alleys were typically built to service buildings and were frequented by delivery and waste-management vehicles. But when they are reoriented to serve pedestrians, they bring to a city a potent blend of lifestyle and economic benefits. As well as improving the permeability of city grids, the friendlier proportions of laneways (which feel more intimate than a city’s main arteries) making for comfortable and desirable spaces for walking, shopping and dining.

Take Fish Lane in Brisbane, for instance, which hosts several significant city-shaping projects that symbolise the Queensland capital’s recent ambitions to become a bigger player on the world stage. “Brisbane is changing quickly and is infinitely different now to what it was when we started revitalising Fish Lane more than a decade ago,” says Michael Zaicek, commercial manager for developer Aria Property Group, which acquired a building on Fish Lane in 2012 – an underused former service street in South Brisbane – and began redeveloping. “At the time, we saw such a strong appetite for a sophisticated placemaking project in the public realm.”

When it reopened in 2015, brandishing a new residential offering and three hospitality venues, it garnered instant acclaim – and foot traffic. Following this initial success Aria pressed on, bringing in public art, acquiring more buildings along the laneway for adaptive reuse, and installing street lighting throughout the area’s public spaces. It’s a combination that has proven so successful that Fish Lane now has a full-time precinct co-ordinator, who is responsible for organising public events, from markets to concerts. “There wasn’t a master plan, it’s just evolved organically into a positive feedback loop,” says Zaicek. “The more we invest in the laneway, the better the outcome for everyone.”

Today, South Brisbane is the city’s fastest-growing residential area and more than two million people pass through Fish Lane annually. Brisbane’s laneways were nearly extinguished in the 1980s; now they’re some of the most sought-after addresses in town. “Ten years ago Fish Lane was a very uninviting place,” says Zaicek. “We’ve reclaimed those nooks, crannies and otherwise unusable spaces and now I see opportunities everywhere.”

It’s a lesson that Melbourne is intimately familiar with. In the 1990s, confronting a precipitous decline in commerce and visitation, the city centre decided to rethink itself. “Growing up in Melbourne in the 1980s, you could literally see tumbleweed blowing down the streets of the city,” says Jocelyn Chiew, Melbourne’s director of city design. “So the City of Melbourne decided to use its laneways to attract a critical mass of visitors and residents.” In 1994 just 300 metres of the lanes within its urban grid were accessible. Now, following a decades-long effort to convert, reactivate and reinterpret its alleys, there’s more than 3km of traversable laneways.

The roots of this transformation in the Victorian capital can be traced to Postcode 3000, a programme that incentivised developers to build in the city, beautified and greened up streetscapes and boosted the city centre’s residential population. Once the laneways had been cleaned up and repopulated, a host of red-tape-cutting changes, such as small-bar licences, lower rents, active street frontage requirements and retail footprint limits, encouraged fledgling bar owners, retailers and creative entrepreneurs to move in, injecting round-the-clock vibrancy into the network. And the work hasn’t stopped: Chiew and her 50-strong multidisciplinary design team are constantly tinkering with the laneways, from increasing safety through better lighting to ensuring that each one feels distinct and different. Documents, such as the Central Melbourne Design Guide, inform designers, architects and developers working on the city’s built form. “But you also want to maintain consistency and curation across the whole network. It’s an ongoing investment,” says Chiew.

Meanwhile, Sydney, which has always had a complicated relationship with its heritage spaces, is still recuperating from the state’s controversial, now abolished, lockout laws, which saw entry to bars (and the potential for nightlife) stop at 01.30 in the city centre. Despite those challenges, several long-term infrastructural bets, from the new metro line to the pedestrianisation of George Street, one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares, have recently been delivered to instantaneous success.

These landmark city-making projects, and the dynamism that they’ve returned to the city, have assisted with another of Sydney’s key goals: reviving and rediscovering its historic laneways. Since 2008 the City of Sydney-backed Live Laneways revitalisation strategy has brought dozens of alleys – including Ash Street, Angel Place, Tank Stream Way and Bulletin Place – back to their best. Throughout town, with funding through Live Laneways, sculptures, projections and even native micro-forests have been installed on laneways to transform them into pleasant refuges between Sydney’s busier, broader streets. With government-supported business alliances, such as YCK Laneways (a consortium of small bars in Sydney), and a new plan to spruce up Chinatown and its warren of lanes, these small streets are becoming a big part of the agenda.

Sydney’s private sector is pitching in too. By the harbour, mixed-use precinct Quay Quarter Lanes, completed in 2021, is a seamless blend of new and heritage buildings across an entire city block, all interwoven with a cross stitch of laneways. Previously dead-end lanes have been unblocked; apartments on the upper floors ensure a residential character and a mix of street-level businesses, from a handmade-pasta shop to a beloved banh mi spot, cater to hungry office workers. Miniature plazas and recesses encourage anyone who stumbles upon these laneways to sit down and take a beat.

“Australians like to abbreviate things so no wonder that we like laneways,” says Adam Haddow, director of Sydney architecture studio SJB, one of the firms that worked on Quay Quarter. “As shortcuts through our cities, they’re like a physical abbreviation but we want to make sure that they’re also places where you can linger.”

While projects like Quay Quarter Lanes relied on existing laneways, its success in Sydney is inspiring a new approach: making new laneways the focal point of new developments. That’s the brief for SJB’s latest project, Wunderlich Lane, in the inner-city neighbourhood of Redfern. The precinct’s centrepiece is a long laneway thronged by high-end restaurants and shops. But just like the historic laneways that it is based on, Wunderlich Lane improves liveability and vibrancy for everyone in the area. “When we do a private project, we always think about how we can generate public good,” says Haddow. “So we built the lane around the existing supermarket and kept that key community infrastructure.” Wunderlich now draws crowds from around Sydney without displacing long-time locals.

Australia’s successful laneway love affair isn’t slowing down. It’s a sign that sometimes focusing on our most forgettable streets can have the most memorable impact. Perhaps, if we want to get a real sense of a city’s trajectory, we should examine how it treats its least glamorous and lowest-visibility spaces, as opposed to its most conspicuous ones. And laneways are a great place to start – if you can find them. —

How to design an Antipodean laneway

Australian cities have a knack for transforming laneways into thriving urban pockets. Here are some design and policy moves that can replicate this success.

1.

People first

Laneways should favour comfortable walking and easy talking, with limited vehicle access. Remove obstacles, bollards and curbs, and add good lighting.

2.

Use the finest finishes

Invest in custom street furniture, signage and visually rich, tactile materials, rather than painted concrete or cheap off-the-shelf seating. A laneway’s unique sense of identity will draw in the curious.

3.

Activate building frontages

Many laneways are lined with blank façades so create visual interest by adding windows or shopfronts. Invite retail and small hospitality ventures, particularly cafés, to take up tenancy.

4.

Mix the offering

Where possible, create opportunities for people to live and work on the laneway, combining residential use with retail and hospitality.

5.

Loosen the license

Relaxing licensing laws and incentivising longer opening hours secures a laneway’s reputation as somewhere fun too.

Shoppers in Hong Kong have traditionally congregated in the city’s well-stocked central neighbourhoods but many are increasingly venturing a little further out for their retail fix. A 15-minute drive will take them to The Repulse Bay, a new destination in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, which has undergone a remarkable two-year transformation courtesy of The Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels, Limited.

The beachfront property, which brings together residential units and specialist retailers, is on the site of a former colonial-style hotel. From its opening in the 1920s to the early 1980s, The Repulse Bay Hotel was a glittering institution that welcomed glamorous guests including Ernest Hemingway and Marlon Brando. In more recent times, however, it stood largely forgotten. But The Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels has given it a new lease of life and the complex is drawing more visitors to the southern side of the island, thanks to an impressive overhaul of the tenant mix. The group has focused on boutique retailers instead of mainstream luxury brands, turning the site’s shopping arcade into a hub of best-in-class bakers, restaurateurs, florists and fashion designers.

A trip to the bay now comes with the promise of making fresh discoveries. Tapping into an appetite for all things Made in Japan, several businesses from the country have set up shop here, including workwear brand Human Made. Visitors can also pick up rugs and embroidered kaftans at lifestyle shop Inside, jewellery by accessories brand Via de Lourdes and plenty more.

“Many years ago we had brands such as Christian Dior but, right now, we wanted to look at specialists rather than all of the usual shops,” says Olaf Born, who oversaw the transformation as the general manager of The Repulse Bay and Peninsula Clubs and Consultancy Services. Monocle meets him in The Verandah, the restaurant and central landmark of the complex, situated almost precisely where the hotel’s famous live jazz concerts used to take place in the 1930s.

“We also have to take into account the 402 apartments that we have to provide amenities for,” says Born, pointing to the charming residential complex. Here, locals relax on the lawn and families can be seen heading down to the beach in groups. There’s a strong sense of community and the team at The Repulse Bay seeks to nurture it further with monthly cocktail meetings, at which residents are able to share their views on the development of their neighbourhood.

“We looked back at the history of the south side,” says Born. “This used to be The Repulse Bay Hotel, where people would come on holiday and there would always be events happening. Even if we don’t have the hotel, we want to recreate that ambience and make it a destination in Hong Kong again.”

Also joining the neighbourhood are home-grown businesses Caffé Parabolica, Bakeshop Parabolica and florist Blackbird Conservatory, complementing the existing mix of grocers, restaurants and fashion brands. Visitors and residents alike can sip good coffee, pick up Japanese-inspired baked goods and find plants and floral arrangements to brighten up their homes. The bakery and café are already attracting more than 10,000 visitors a month, many of whom come for the popular cream latte and egg sando (a simple sandwich made using thick shokupan bread). The ambition is to double this number by the end of this year.

“We want to assist brands that might not have a presence in Hong Kong, as well as local talent,” says Born. “That makes things very interesting.” The group’s efforts to keep things fresh also involve a series of temporary pop-up shops, collaborations and artist residencies. In December 2024, the shopping arcade hosted a two-day camping-themed event with Japanese brand Visvim. Working with independent businesses aligns with The Repulse Bay’s broader ambition to highlight heritage and great design. Japanese labels, such as Human Made, have proven to be particularly good matches, given their focus on handicraft.

Hong Kong residents often joke about Japan being their second home. Many make trips to the country multiple times a year and there is a long history of cultural exchange dating back to the early 20th century. That’s why bringing Japanese touches to The Repulse Bay is a smart move – and it’s paying off.

“We have certainly seen a much younger crowd coming from central Hong Kong, not just the south side,” says Born. “We have a lot of younger people using the terrace at [pan-Asian restaurant and bar] Spices. Residents are becoming regulars now too.” It’s a welcome sea change. With new ventures in the pipeline, including markets and brand-specific events, Born is confident that The Repulse Bay can help to re-establish the area as a buzzing Hong Kong destination.

His ambitions run far and wide, encompassing everything from orchestrating the return of tea dances at The Verandah restaurant to opening an archive room that could tell the story of the illustrious development. “There’s a huge history here and we want to find a way of displaying it for future generations, as well as today’s younger people,” he says. Resonant historical references can be found throughout the arcade; in the courtyard, roses are currently being planted to pay homage to the flowers that once encircled the gardens of the hotel. Downstairs, Human Made uses bellboy trolleys as clothing racks. These are filled with vintage-inspired workwear, including chino trousers and elegant bowling shirts. Around the corner is Human Made’s food shop, Curry Up, which is its first international outpost.

“We have seen more brands reaching out to us that wouldn’t have done so in the past,” says Born. “We hope to be a springboard for upcoming designers who might then move to a more central spot for a bigger space. We understand that they’ll outgrow us but that’s fine because it keeps us fresh and gives us space for new tenants.”

Though the transformation is expected to be completed this year, there will always be room to experiment with retail concepts, introduce new names and encourage locals to visit the south side more frequently. “It’s a collaboration between ourselves, the brands and the community,” says Born. “We have beautiful surroundings, a true boutique feel and a few of the very best things.”hshgroup.com

Alex Wilcox once came up with a plan to beat Concorde. In 1997, as a young pilot from Vermont, Wilcox had worked his way up the ranks at Virgin Atlantic and presented an idea to his boss, Richard Branson. Wilcox argued that by flying Gulfstream jets with lie-flat seats from Westchester County Airport in New York state to London City Airport, Virgin could beat the supersonic jet on door-to-door travel times for customers in Connecticut. Travelling to JFK International Airport was time consuming; ditto the trip from Heathrow to the City of London. Wilcox saw that the use of smaller, underutilised airports could speed up the overall journey, even via a slower aircraft.

Virgin ultimately declined to fund Wilcox’s proposal. Yet this rejection didn’t quell his knack for hatching ambitious ideas that could disrupt the aviation sector. Now, almost 30 years later, Wilcox is captaining JSX, the operator of a fleet of hop-on, hop-off jet services across strategic North American routes that has the wind under its wings right now.

The draw of a semi-private service such as JSX is that flights tend to be quicker, and occasionally cheaper, than the First-Class equivalent offered by legacy carrier. JSX passengers arrive at its hangar in Dallas as little as 20 minutes before their flight, toss the valet their keys and board for Cabo San Lucas, Miami or Scottsdale. The seats have Business-Class legroom with Starlink-enabled wi-fi, while flight attendants keep the snacks and drinks flowing. Though other aviation entrepreneurs have tinkered with this model – JSX’s leading competitor, Aero, flies to sun and ski destinations from Los Angeles, and continues to expand its reach – JSX has built a coast-to-coast network with multiple flight hubs and was expected to exceed €485m in revenue in 2023 (JSX does not disclose its revenue figures). That figure is a tiny fraction of the €24bn that the three US legacy carriers each made last year but JSX is encroaching on market share among fliers who’ve grown weary with the rigours of traditional air travel.

“We have what really matters in business, which is a million customers who absolutely love us,” Wilcox tells monocle in a conference room overlooking JSX’s fleet of Embraer erj 135s and 145s. “We’re profitable and we’re growing.” More 145s are in the pipeline to join the fleet this year and the route map is likely to expand, with the lucrative New York-Florida corridor and destinations west of the Rocky mountains clear opportunities.

Headquartered in a 1950s hangar in Dallas Love Field airport, JSX seeks to provide a level of hospitality that’s increasingly rare in the assembly line world of domestic air travel – and some of its top hires came direct from hotels. On the brisk winter morning that we visit, valets are parking Cadillacs and luxury Ford pick-ups, while others are loading luggage carts, bellhop style. JSX’s Dallas hub welcomes, at most, 15 flights per day with a maximum of 30 passengers per plane – the legal limit to fly under the Federal Aviation Administration’s regulatory radar for “public charter” flights.

Flightplan: JSX’s top five routes

1. Burbank, California to Las Vegas

2. Orange County, California to Las Vegas

3. Burbank, California to Oakland

4. Burbank to Scottsdale

5. White Plains, New York to Opa Locka, Miami

Though the plastic plants and tepid coffee in the departure lounge fail to inspire (a lounge refresh is, we’re told, coming soon), the point, say execs, is that travellers don’t need or want to linger. Indeed, the destinations on the departure board reflect the two sides of JSX’s proposition: passengers in stylish puffers are boarding a flight to Taos, New Mexico, a delightful but hard-to-reach ski town; while across the hangar is a crowd en route to Las Vegas dressed for the links in khaki shorts and golf shirts. Two staffers working the gate whisper discreetly that World Wrestling Entertainment scion Shane McMahon is boarding one of the aircraft. JSX has a regular vip clientele, and Wilcox pauses multiple times during our interview to field calls from a senior Trump administration official who’s frustrated by poor communication about a weather delay on a jsx flight to Florida.

Security is swift and completed without scanning wands and conveyor belts, and boarding takes place on the tarmac. A stand full of red JSX-branded umbrellas are stationed conveniently at the gate to weather any Dallas downpour.

To explain JSX’s niche, Wilcox references the hotel industry. “Between Motel 6 and Aman, there are 100 hotel brands,” he says. But between domestic First Class on a legacy carrier and a private jet, there was nothing. When Wilcox asked business travellers why they would spend four-figure sums on a private jet hop between Los Angeles and the Bay Area, the answer was clear. “They didn’t want to spend an hour and a half at the airport for 45 minutes on an aeroplane,” he says. For long-haul flights, the pageantry of the international airport remains relevant. For short domestic trips, it can be a hassle.

It’s the kind of insight that Wilcox gleaned during a career spent between the cockpit and the C-suite. Raised in Vermont as the son of an American father and Swiss mother (he holds US citizenship), he fell in love with aviation as a child taking transatlantic flights to see family. JSX’s red livery is a homage to his Helvetic roots – when viewed from the top down, the colour scheme resembles the old Swissair logo.

Wilcox can rattle off a colourful CV, including a stint as a rock-band manager. He interned for Southwest Airlines founder Herb Kelleher, worked for Virgin Atlantic, joined David Neeleman to launch JetBlue and was recruited by now fugitive Indian billionaire Vijay Mallya to start short-lived South Asian carrier Kingfisher Airlines. “There are legions of people who have failed in this industry,” says Wilcox. “Only a handful actually made something that has lasted, and I’ve been lucky to work for at least four of them.” From his various mentors, Wilcox says that he learnt the importance of taking care of his crew. He also became a believer in the efficiency of fielding a single aircraft from his years at Southwest, where every pilot could fly every plane. “Low cost is the key to winning this business,” he says.

He also adopted a roll-up-your-sleeves mentality. On our hangar tour, Mark Fields, an aircraft maintenance engineer with 20 years of experience, says that he has seen Wilcox in action in a crisis. “A CEO loading luggage during an ice storm?” says Fields. “Now that’s a man you want to work for.”

There’s no aviation-industry secret weapon for avoiding inclement weather or turbulence in the travel market. But when the skies are clear, JSX offers a tantalising alternative to the conventions of air travel that we’ve become accustomed to, from time-consuming queues for security to a lingering sense that, among some legacy carriers, value for money has leaked from the overall experience. For passengers who want to get from A to B quickly, comfortably and conveniently, this is a disruptive player worth watching.www.jsx.com

The Nairobi neighbourhood of Tigoni is only 200km south of the equator but its refreshing altitude of 2,000 metres above sea level offers some breezy relief from the heat. A cool morning mist is slowly clearing as, under the watchful gaze of a bemused colobus monkey, Monocle struggles to locate the Rewildings building site.

The residential project is the work of architect couple Carolina Larrazábal and James Mitchell. While their studio is nearer downtown Nairobi, the couple put down roots in Tigoni thanks to a manageable commute and easy access to nature. They fell in love with their current site while looking for buildable land. “It was the first one we viewed,” says Mitchell. “We both had that kind of fuzzy feeling when you know that something is right. It really clicked.”

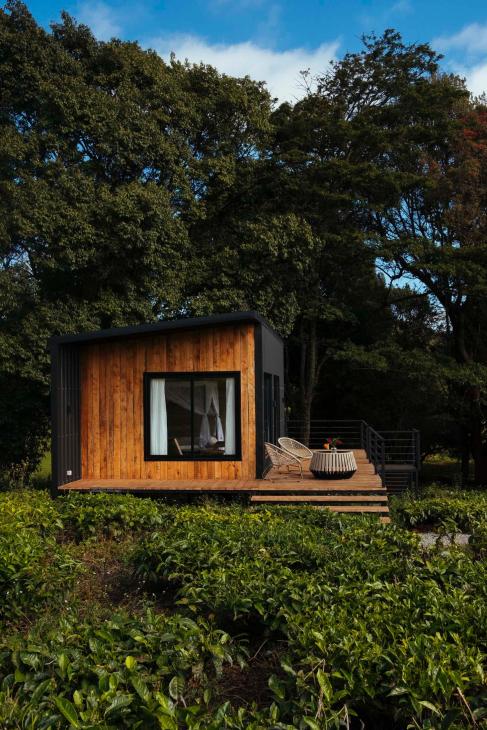

The 33-year-old Spaniard and 36-year-old Scot designed seven low-carbon houses here, including a home for themselves. When Monocle finally locates the turning, the site is brimming with activity. A team of carpenters is cutting sustainably sourced timber, and the smell of charred wood is in the air: the exterior of each house will be treated with the Japanese yakisugi technique that involves charring each panel of wooden cladding. The four-hectare development is both residential and an act of conservation. Surrounded by tea fields, it sits between two forests. By removing most of the tea bushes and replanting native flora, the couple hope to reinstate some forest cover and ecosystem for the likes of the monkey still watching our progress.

Larrazábal and Mitchell aren’t alone in trying to escape Nairobi’s traffic-clogged downtown for the tranquil hills of Tigoni. Several (hugely improved) roads, including one that connects directly to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, have brought the capital within easy reach of a highway, then down lanes lined with banana and acacia trees in just an hour.

With the UN moving more jobs to Nairobi, its largest base in the Global South, property prices have increased by 25 per cent or more in some inner-city neighbourhoods. Tigoni offers value besides its ecological allure; you can buy a three-bedroom townhouse with a small garden in a new development for about €270,000, while a more upmarket four-bedroom Rewildings house will set you back closer to €730,000. A generational change among Tigoni’s traditional tea farmers, coupled with the declining value of the crop, has resulted in landowners seeking to repurpose agricultural land. One of these is Segeni Ng’ethe. The 48-year-old tech entrepreneur grew up on his father’s tea plantation and dairy farm, Gathoni Park Farm, a short drive away from Rewildings.

A few years ago, Ng’ethe decided to leave tech behind and take over the parental plot. Moving from start-ups to running 97 hectares of tea and cattle-fodder plantation was a steep learning curve. “It was not an easy transition, especially on the farming side,” he says. “I remember when I came here, one of the first appointments I had was with a mole hunter. I didn’t know that you could find people with careers in mole hunting. But I was, like, ‘Welcome to the new world.’ We planted avocados and they were all disappearing because of these moles [tunnelling around the tree roots].”

Several equally humbling experiences followed but Ng’ethe transitioned Gathoni from an agricultural business into an eco-tourism destination with a mix of farming and hospitality. He leased out his dairy to a cheese producer and turned the picturesque spaces on the farm into a flower garden, fragrant with the smell of lavender, rosemary and geranium. The gardens are available for bike tours, picnics and weddings. “On weekends, we have all generations, big families, small families, couples,” says Ng’ethe over a cup of tea grown on his own plantation. “Nature is the new angle for recreation. Just having access to the open spaces, the sun, fresh air, listening to birds singing. People just lie down on a blanket and look up into the sky. That’s something that has been growing, particularly among a younger generation of people who want to be outdoors on weekends, especially those who live in apartment buildings.”

Recently Ng’ethe teamed up with his neighbour, Mikul Shah, and built several “tea-pods” (cabins on stilts set in his tea fields) that are available for short-term rental to Nairobians who want a weekend away or tourists who are looking to break their drive to the Masai Mara, 200km to Nairobi’s west. Shah and Ng’ethe are also exploring ideas and financing to open a small hotel, restaurant and conference facility by the nearby lake.

If infrastructure has made Tigoni accessible, Shah and his jewellery-designer wife, Ami Doshi, have played a key role in rebranding the enclave from sleepy to cool. The couple originally rented The Lakehouse – a dwelling with scenic views of the garden and the lake – as a family retreat during the pandemic. “We fell in love with the fact that we’re surrounded by nature and trees that are 90 years old,” says Shah, who was born in coastal Mombasa and lived in London.

The path to The Lakehouse leads through a small, lush forest where the canopy filters the midday sun. The bountiful garden hasn’t changed much since its inception about 70 years ago. The ruby red flowers of an orchid cactus, part of the original landscaping, explode in full bloom. Bushes of giant philodendrons and fern lead towards an imposing flat-top acacia tree by the lake.

Both Shah and his wife saw the potential in using this space to bring people together in Tigoni. The idea for a supper club set in their conservatory with unhindered views of the lake and garden took shape. The tables are decorated with sculptural floral arrangements. Once a month they host wine tastings, culinary pop-ups and birthday parties. The couple are now in the process of closing on a property nearby. “Even properties that are slightly further from what was traditionally Tigoni are calling themselves ‘Tigoni’, because it has an aspirational name attached to it,” says Shah.

Infrastructure and the availability of land and housing aside, Shah thinks that another factor that has been instrumental in the growing appeal of moving here is schooling for the children of people looking to put down roots. “There is an international school that offers a new way of teaching,” he says. “It’s a forest school. Very recently it started taking students up to age 18.” The school, Woodland Star, is next to Brackenhurst forest and students are encouraged to spend their time outdoors. A repurposed Volkswagen campervan serves as an outdoor learning space. About 60 per cent of the children enrolled here travel from Nairobi, while the other 40 per cent live in Tigoni, though these numbers are slowly shifting the other way.

Sunny Im, whose son is due to start at Woodland Star shortly, lives around the corner from the school. “It is an exceptional school,” she says. “People commute into Tigoni for it. If you want to be in Tigoni, if you want the nature and the quiet and you have a child, you kind of have everything in one place.” Im works as a talent strategy consultant for an investment firm that focuses on the renewable energy sector in Africa.

Im was born and grew up in Nairobi. After leaving Kenya to attend college and graduate school in the US, she and her husband returned to East Africa to work in neighbouring Uganda. A day out in Tigoni while visiting family in Nairobi led them to buy land and build a house and guesthouse in the tea fields. Inside, light streams in through contemporary floor-to-ceiling windows. Teak flooring warms the modern, sleek design, while two fireplaces – indoor and outdoor – can be lit during chilly Tigoni evenings.

Buying land and building from scratch is possible but it’s not the only way to secure property in Tigoni. For those who like the quiet but not the gardening, apartments and townhouses with access to an expressway into central Nairobi are now on the market, while projects that require renovation, such as older farmhouses and 1970s bungalows, are also available to rent or buy. Sakina Seif and her family moved here to have access to more living space. She and her American husband commute to Nairobi to run their business, Kentaste, which is the largest manufacturer of coconut-based products in East Africa.

Three galleries or collectors to meet:

1.

Check in with Erica and Hellmuth at the Red Hill Gallery. They may show you their private collection of contemporary East African art. Join the mailing list for the vernissages.

redhillartgallery.com

2.

Get in touch with Thaddeus Mutenyo Wamukoya, affectionately known as Tewa. He organises pop-ups and private viewings of contemporary art from Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda.

tewasartgallery.com

3.

Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute is on the edge of Nairobi, a short drive from Tigoni. It’s a non-profit visual-art space.

ncai254.com

Sensing an appetite for gastronomic variety, Seif opened Nifty, a café that overlooks Brackenhurst forest and has become a popular spot for brunch and after-work drinks. With more and more young professionals moving to Tigoni, hospitality is catching up. That, in return, has made the enclave more attractive to day-trippers. Set in a refurbished dairy, The Fig and Olive, a recently opened café, deli and grocery shop, offers everything from poached eggs to quality ingredients such as bronze-die-cut pasta and organic chicken. At Como, owner and chef Stephanie Kiragu incorporates regional ingredients such as tree tomatoes into her cooking. Organic farms, including Forest Foods, have excellent produce that can be delivered.

The Limuru Country Club, equidistant from The Lakehouse and Nifty, is a good place to meet and mingle. On a Saturday afternoon, the smell of barbecued nyama choma wafts through the air. After hitting a ball around, the mostly male members of the club congregate on the terrace to tuck into a portion of grilled meat with kachumbari, a lime-juice-infused tomato salad. The club has access to an 18-hole golf course, a tennis court and a pool. It’s a favourite of both the Tigoni elite and younger newcomers such as Mitchell and Shah. Every two months the nearby Red Hill Gallery has a vernissage showcasing East African artists.

Now that Tigoni’s property secrets are out, the challenge will be to preserve its relative serenity. There are concerns that improved commuting times and open spaces could lead to the uncontrolled development that has seized other parts of the Kenyan capital. “The change is positive,” says Segeni Ng’ethe. He is confident that Tigoni’s unique landscape will not be erased as development draws closer. “It’s bringing new ideas and different spending power.”

Tigoni calling: Neighbourhood knowhow

The cost of renting a flat and the agent to call:

Rent a new two-bedroom, two-bathroom cottage for €1,500pcm from a private landlord. Call Quentin Mitchell at Langata Link Real Estate. Or explore the area: word of mouth gets you the best deals.

langatalinkrealestate.com

Best street to live on:

St George’s Road, within walking distance of the lake and an equestrian centre. It also has access to two roads that lead to Nairobi.

Best school:

Woodland Star. An international school on a beautiful green campus.

woodlandstarkenya.com

Groceries and cafés?

Greenspoon is an excellent on-the-day delivery service, with artisanal groceries. Try the region’s tea at The Fig and Olive, then pick up your bread and pastries, as well as the latest copy of Monocle, at The Good Grain in town. Head to Brown’s for local cheese.

greenspoon.co.ke; +254 795 347488; the-good-grain.tappi.ke; brownsfoodco.com

Running route that shows the enclave at its best:

Run through the tea fields around Kiambethu tea farm, explore Brackenhurst forest and head down to the lake. Breathe deep: the altitude can take some getting used to.

Closest airport and how to get there:

Fly into Jomo Kenyatta Airport and take a taxi. It’s a 55-minute drive to Tigoni.

The biggest improvement:

Road upgrades have reduced travel times and increased commuting options to Nairobi.

The area is missing:

A good bookshop.

Only here:

It’s one of the few places in Kenya where you can walk, cycle or ride a horse without falling foul of trespassing laws or the wildlife getting in your way (or chasing you).

What to do with a culturally significant home that’s too expensive to maintain but too precious to abandon? That was the conundrum facing Zuzana Kadleckova, whose family owns Villa Volman, a 1930s masterpiece of Czech modernism. “Can you imagine living here today?” says Kadleckova with a laugh. The former marketing consultant turned full-time curator is on hand to meet Monocle to explain her answer to our original question: under her direction, the renovated villa has been transformed into a museum. “The villa is breathtaking but the scale is something else entirely,” she says. “Every walk from the bedroom to the kitchen would make you think twice.”

Located down a long drive in the small town of Celakovice, a journey of about 30 minutes from Prague, Villa Volman is a striking work of architecture with a chequered past. Across four storeys, it has a grand dining room, games room, an enormous open- plan living space, stately bedrooms and grand bathrooms, as well as staff quarters and a sweeping rooftop belvedere, all enclosed in architecture defined by crisp lines and intersecting planes.

Designed by Jiri Stursa and Karel Janu, two radical young architects whose Marxist principles saw them typically work on social housing rather than private villas, it was commissioned by industrialist Josef Volman in 1937. He ran a machine-tool factory and built the home on an estate next to a public park used by his employees for leisure pursuits. The house, intended for the widower and his daughter, Ludmila, reflected the ambitions of both its owner and what was then Czechoslovakia, as the man and the country enjoyed newfound prosperity that required striking modern architecture to reflect their progress, prowess and contemporary tastes.

This ambition was short-lived, however. Volman died four years after moving in and Ludmilla fled to France following the communist revolution in 1948, which resulted in the nationalisation of the villa. It was used as a kindergarten for decades before being abandoned in the 1990s. “The new chapter starts in 1996 with a set of new owners that included my father,” says Kadleckova. “My family is from Celakovice, and we are entrepreneurs producing machine tools, much like the Volmans. So you could say our family company is a natural successor.”

Kadleckova’s father, with the help of tak Architects’ founder Marek Tichy, spent the better part of 15 years renovating the home, which had decayed dramatically – rusted steel protruded from fractured concrete, windowpanes were shattered and the travertine cladding lay in fragmented ruin. “Tichy is one of the best-known Czech architects specialising in the restoration of the architecture of the first Czechoslovak republic,” says Kadleckova of the decision to work with the Prague-based creative, who matched the original material and colour palette of the villa in his restoration.

Under Tichy’s guidance, the travertine cladding and terracotta tiles were replaced or restored and bold splashes of colour were reinstated. Details and bespoke fittings, such as an oak staircase with a balustrade perforated with circular openings, were returned to their original and rightful majesty. Attention was also paid to the exterior spaces and façades, with the garden beds surrounding the rooftop belvedere replanted and the grand porte cochère (covered porch) given a lick of paint.

The villa has been finished with classic modern furniture – the perfect backdrop for the activities selected by Kadleckova that invite life to continue in the building. “There’s no better way to tell the stories of modern architecture and design than within the walls that lived through the 20th century,” says Kadleckova of the decision to open the space to the public with considered programming.

“When we welcome you as though it were your own home, you’re immersed and captivated with all your senses. It’s a completely different level of engagement compared with learning about it from books or attending lectures.”

The museum is open for guided tours and one-off events, such as rooftop yoga. But there are also opportunities to stay overnight; guests can contact Kadleckova and join the waiting list. The highlights, however, are moments when the spirit of the original architecture is brought into harmony with other creative industries, including live music and performance art. “We can host intimate concerts,” says Kadleckova. “Artists absolutely love performing here. After all, who else has a 170 sq metre living room? It brings fresh energy to the villa while still respecting its original character.” — vilavolman.cz

Villa Volman timeline

1937

Industrialist Josef Volman commissions Jiri Stursa and Karel Janu to design a grand home

1939

Villa Volman is completed to Stursa and Janu’s exacting modernist design

1948

The Volman family flees Czechoslovakia following the communist revolution

1952

The villa is nationalised and converted into a kindergarten

1979

It’s added to the Czech Central List of Immovable Cultural Monuments

1990

The villa is abandoned following the fall of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia

1996

Zuzana Kadleckova’s family become part owners of the villa

2003

Renovation works begin under the direction of Marek Tichy

2018

Restoration work is completed

2022

Villa Volman opens to the public as a house-museum