In a residential district on the outskirts of Switzerland’s biggest city is the newly opened University Children’s Hospital Zürich. Among the site’s high-rise buildings and classically inspired, stone-clad medical- research facilities, the building stands out – not just because of its atypically low height but also as a result of its timber and concrete exterior. Nicknamed Kispi, it was designed by Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron as an alternative to sterile medical facilities.

“Wherever possible, we wanted to use wood,” says Christine Binswanger, a senior partner at Herzog & de Meuron and the person in charge of the project. Timber’s ability to support healing is well documented; studies have shown that simply looking at wood cladding can ease the strain on your sympathetic nervous system. However, using the material in a clinical setting with strict hygiene requirements isn’t easy. By working closely with the Eleonorenstiftung, the healthcare foundation responsible for operating the hospital, the architects found a solution that beautifully balances practicality and design.

“The foundation was convinced that architecture could help to make the stay of young patients and their relatives easier,” says Binswanger, who explains that convincing the Eleonorenstiftung to go against the grain wasn’t a challenge, even if conforming to strict medical regulations was. “It was with this goal in mind that it supported us in finding a way to design the Kispi differently.”

And different it is. It’s set apart not only by its low-slung, mostly wood-based structure but by its innovative interior floor plan. Binswanger and her team took inspiration from the layout of a typical Swiss city district’s street grid. Every floor is organised along a central artery, which branches into smaller “lanes” that front open-air courtyards. The latter, which are filled with native plants, introduce natural light, which has been shown to reduce patient recovery time, into the centre of the building. These courtyards offer moments of respite, allowing children and their carers to pause and feel the sun on their skin.

By integrating pockets of greenery wherever they could, the architects sought to foster a calming, uplifting atmosphere. “The courtyards ensure daylight and access to what’s outside,” says Binswanger, who adds that the interior windows on every floor also offer calming views of these verdant spaces. “And the overall use of natural materials such as wood gives patients a sense of connection to the outside world. The differently planted courtyards help to make orientation for those inside the building easier too.”

This thoughtful, city-like organisation takes the needs of both patients and staff into account. A clear hierarchy of pathways allows medical teams to move easily between treatment areas, offices and patient rooms. The architects carefully planned the layout so that distances between key locations – such as a pre-surgery waiting room and an operating table – would be short, making transitions smooth and reassuring for children. “Places have their own identity along the ‘main streets’ of every level,” says Binswanger.

Every storey of the building is dedicated to a different function. Emergency and ambulatory rooms are on the ground floor; offices on the second; and patient rooms for overnight stays, along with dedicated rooms for specialised medical care. are on the third floor, where wooden finishes and views of nature create a soothing environment. The rooms are made to feel like a self-contained wooden cottage, complete with small nooks that provide moments of escape for children, creating a space that feels safe, inviting and tailored just for them.

“Each of the patient’s rooms is like a cosy house,” says Binswanger. “They feel private. Last week a mother told us that she came here and felt safe. That, perhaps, tells you more than any description. We tried to create an inviting atmosphere for young people, reflected in details such as the round windows in the lift cabins, which are at a child’s height, so that the little ones can see something that the adults might not even notice. At the same time, there are places where adolescents can retreat and find privacy when they are not in therapy.”

In designing the Kispi in a way that embraces nature, puts children first and keeps practicality in mind, Herzog & de Meuron created not only a place for treatment but a sanctuary for children, their families and staff. The building feels like a warm embrace – a hospital that saves lives while improving people’s life quality. It sets a new benchmark for what a children’s hospital should be: a place where architecture helps to support the care and wellbeing of everyone inside.herzogdemeuron.com

Five considerations for building better

Many factors that make an office or a home appealing can apply to hospital environments and aid people at difficult moments of recovery.

1.

Greenery

Studies have shown that exposure to plants can help to improve mental health and reduce anxiety. It has also been linked to faster recovery from illness or surgery; a recent US study found that users of hospital gardens in California had improved health outcomes.

2.

Natural light

Flooding hospital spaces with natural light, whether through internal courtyards, light wells or big windows, aids patient recovery as daylight helps to regulate circadian rhythms and enhance rest. It also counters depression and weariness.

3.

Materials

Soft and tactile finishes create an inviting atmosphere that can reduce stress levels. Natural fibres are important too. Their use in interior environments is reportedly linked with reductions in post-operative recuperation times.

4.

Acoustics

Sound-absorbing materials can improve patient comfort by creating quiet spaces for recovery. They can also enhance staff effectiveness by eliminating noisy distractions.

5.

Ventilation

The consistent flow of fresh air through interior environments lowers the spread of infectious illness and reduces stress.

The Meise Botanic Garden just north of Brussels is one of the world’s largest conservatories of endangered plants. Apart from ensuring the security of rare species, the garden also enables the public to view and enjoy these rarities, an experience enhanced by its new Green Ark Project. This new pavilion, which doubles as a learning hub, is defined by parabolic wooden slats that curve above visitors’ heads.

“We were pushing the boundaries of the achievable,” says architect Armand Eeckels of NU Architectuuratelier, the Ghent-based firm behind the design. “The simple logic was that if we could build a model one tenth of the scale in wood, then we could build it in reality.”

The project wasn’t exclusively about aesthetics, however. The Ark also hosts practical technological features, such as recycling the rainwater that falls on its roof for irrigation. The structure is made from a sustainable, organically modified timber called Kebony, which replicates the properties of treated hardwood.

If an impressive botanical garden is to host more than 10,000 endangered plants, impressive architecture is needed to match. The Green Ark does just that.

nuarchitectuuratelier.com

The brutal climate of Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, means that architecture here must not only offer shelter but be in harmony with nature; to endure winter cold, darkness and relentless winds while also embracing the transient brilliance of Arctic summers. Nuukullak 10, an apartment building in the city’s Entreprenørdalen district, rises to this challenge.

Designed by Copenhagen-based studio Biosis, the project is a singular building containing 45 apartments (for young professionals and families) strategically arranged around a central courtyard, allowing for sea and mountain views. This architectural form, with visual links to nature, shouldn’t come as a surprise given that Biosis’s design philosophy advocates minimising environmental impact and creating projects that are in harmony with the natural world. In Nuukullak 10, for instance, instead of flattening the sloping site, the structure steps with its natural contours, reducing the need for rock blasting and preserving critical natural habitats. Biosis also developed the horseshoe-shaped layout to break down the fierce winds and maximise sunlight during the dark winter months.

“The design was shaped by thorough studies of local wind patterns and daylight hours,” says Morten Vedelsbøl, Biosis’s co-founder. “This allowed us to map out a microclimate and refine the building’s form to respond effectively to its natural surroundings.” The result is a building that offers comfort, connection and beauty to those who call it home.

biosis.dk

Designed as though imprinted by a waffle iron, Valletta, Malta’s capital, is a 16th-century gridded city whose streets are bound by a perimeter of stone bastions. Here, like in many other southern European and Mediterranean cities, townhouses were once built to serve multiple purposes – commercial or production spaces could be found on the ground floor with living quarters above. These centuries-old homes provided the original mixed-use, live-work model that appeared to lose its sheen in Malta in the late 20th century, with light industry moving beyond the city centre and Valetta’s workers commuting to the capital from cosy conurbations, rather than from the upper floors of their homes. But there’s still merit in the model for the city’s residents (and those in similarly built metropolises across the globe) and it is something that architect Chris Briffa is intent on proving.

Born and raised in Birgu, a historic city on the south side of the Grand Harbour, Briffa now lives on Valetta’s St Paul’s Street, which is defined by timber-fronted shop façades and limestone townhouses. “When I told my mum that I was moving to Valletta in 2001 she cried for two days because it was so desolate at the time,” says Briffa as he welcomes Monocle to Casa Bottega, his studio and home, where he lives with his wife, Hanna, and three children, Elia, Mira and Finn. “But I saw potential here and I thought that it was only a matter of time before people recognised what we have.”

And it’s this potential that has been realised at Casa Bottega, a once-abandoned townhouse that Briffa, with the help of his namesake design studio, has converted into seven floors of living and working space. Such a concept – of domesticity and creative labour under one roof – had been on the architect’s mind since arriving in the Maltese capital. Then, as a 25-year-old, he lived alone in an 80 sq m apartment with a bathtub in its living room.

“I guess I sincerely believed that you could set an intention with the kind of house you chose to live in,” he says. “If you want to be a bachelor, you live in a flat with a bath in the middle of the living room. But if you’re moving to a house with three bedrooms and space for a family [you might just start one]. In my case, it happened, even though I didn’t yet have a family or a clue that it would come.”

Work on Casa Bottega began in 2014, with Briffa aiming to restore the original townhouse, which had been divided up, and then build upwards, creating space for growth. “That year was the craziest of my life,” he says. “I met Hanna, and Elia came soon after.”

Briffa bought the house, which dates back to the late 1600s, at a court auction. In its former life, the ground floor was used for stabling horses, their muzzles poking into the internal courtyard. The brief for the building’s new iteration was simple: to host a live-work space in the heart of the city. Briffa quickly moved his studio into the structure’s first floor. “It was just a restored ruin then. The element of preserving the skin and bones of the house happened in phase one, while simultaneously planning, designing and dreaming about phase two,” he says. “The fact that we worked here before we lived here gave us a lot of insight into the building – how it functioned, how it didn’t.”

The result is a structure that transitions from working to living as one moves upwards through its floors. It begins with an entrance for both sets of occupants – family and studio – pulling people through a sparse hallway and then towards the building’s restored semi-outdoor stairwell or its new courtyard lift. On the first floor, Chris Briffa Architects still finds a home. Here, designers’ desks run in parallel with three balconies, which let shuttered light into the orderly room. On the second floor, a sala nobile extends across the entire façade with a bespoke shelving system defining the back wall; this timber composition of black lines and subdivisions holds books, architecture models and Briffa’s swelling collection of design curios.

The next level, entered via a staircase, marks the shift from Casa Bottega’s working area to the family home. In lieu of a physical gateway, the ritual of removing shoes as one enters the domestic space separates the live and work components. Footwear in a gamut of sizes – from toddler and child to adult – coalesces on concrete steps. A shared children’s bedroom comes first, with an ensuite bathroom whose marble offcuts recall the loggia tiling at St John’s Square in Valletta. This washroom is enclosed with glass-reeded timber doors, which reference one of Briffa’s earlier projects, an installation called Antiporta at Palazzo Mora in Venice. It was crafted as an ode to the negotiatory role of traditional Maltese interior porches, which are made from translucent glass panelling.

Up another level and the master bedroom is spartan and blanketed by chalky light, which enters through a low-lying glazed strip. This runs along the room’s external-facing wall, leading onto a shallow glass terrace.

The fifth floor is the heart of the home, which can be accessed by stairs or the courtyard lift. The elevator skips the building’s work and sleeping levels, opening directly into this living area, where a semi-outdoor bathroom of weathered timber is the first space seen as its doors open, introducing Briffa’s fidelity to Japanese author Junichiro Tanizaki. “When we were laying out the building, I said to my team that we should make a folly at the entrance to the lift because it’s a dark space,” says Briffa. “So I took Tanizaki’s book, In Praise of Shadows, and literally transformed it into an interior.”

Walking past the bathroom, you find an Arclinea kitchen tucked around a curved concrete corner, its stainless-steel configuration shimmering in the light that flows in through flanking glass-block walls. Above the kitchen, a solid-oak mezzanine, dubbed the “three-house”, was built for the children to climb up to and occupy, safe within a bordering netted lining. A timber-and-metal stair system – part rungs, part rails, part shelving – connects the two levels. Across the kitchen, a multi-directional sofa becomes the soft centrepiece of the room (Piero Lissoni’s Extrasoft for Living Divani, to be precise). Throughout the day, peachy rays of sunlight enter through breezy curtains that separate the space from the deep terrace that looks out onto the street.

Briffa grew up in his father’s carpentry workshop before studying in Malta, at Virginia Tech in the US and the Politecnico di Milano. This early experience has informed his obsession with how things fit together, his concern for how they are used and the need to design elegance into every object or experience. Like the whole building itself, many of Casa Bottega’s features are intended to do, or be, more than one thing at once. Off the kitchen area, a timber bench serves as a seat for nightly family meals, before extending downwards to become a stairwell, which leads to a laundry room. Beyond that is a half-height den holding and hiding all of the building’s services.

Perhaps the most defining architectural feature of Casa Bottega is the most challenging to see, unless viewed from the upper levels of the building across the street. Its new floors in concertina concrete are held up by two nine-metre-long beams. They are made from precast concrete, produced off-site with factory precision to satisfy the sharp articulation that Briffa envisioned for their external profile; their folds are as crisp as bent paper. This is one of countless design decisions that he nursed tenaciously over the years. “You do become attached to places that you design, especially when you design them for yourself,” he says. “There’s a need, almost, to continue understanding oneself; it’s an introspective process.”

The final levels of Casa Bottega – its terraces and roof – are what bring the building’s private world back into the city. Aside from extending interiors out into the beating sun, they intentionally added a garden to St Paul’s Street – a piece of the city otherwise dominated by limestone, a road and sky. It’s here, in this new green space, that the family spends days and balmy nights with friends; where the separate functions of city life, work and play merge inexorably, allowing Casa Bottega to set a new benchmark for live-work spaces in Valetta and beyond. — chrisbriffa.com

Projects of note

Since opening his studio in Valetta in 2004, Chris Briffa has designed striking spaces in the city, including a public toilet, a restaurant encased in a fortification and his own home. Here are three projects that capture the architect’s ability to interpret local vernaculars in new, irreverent ways.

1.

Valletta vintage

Malta

A collection of converted and curated Valletta apartments grew from one in 2012 to 10 spaces. All are studios that Briffa has furnished in partnership with his wife, Hanna, with hand-picked designer furniture and art collections from the region’s practitioners. The holiday homes demonstrate Valletta’s complex mingling of new and old and how best to live with it.

2.

Tanizaki’s shadows

Gozo

The influence of Junichiro Tanizaki reappears in a sea-facing apartment once blighted by intense easterly sunlight. Just as Tanizaki celebrates the use of shade in In Praise of Shadows, Briffa’s design for this home mitigates the area’s brightness with shadow. Tanizaki’s premise translates into timber lattices, lightweight screens and a neutral palette.

3.

Seaside seclusion

Bahrain

Briffa has an instinct for crafting spaces that either harness or temper the elements. At Reef Guesthouse a giant funnel directs northwestern winds away from the yard of the seaside property in Manama. Inspired by typical Bahraini residential layouts, a sparse selection of travertine, concrete, wood and glass define the space.

In the 2010s the idea of the “internet of things” (IOT), in which physical devices are linked together via the web, began to take off. This was thanks to faster internet connections, the increasing affordability of digital sensors and growing computing power. “When IOT products came out and you could have your washing machine send your phone a notification telling you that it was finished, we realised that everything had got a bit loopy,” says Sam Hecht, who established creative studio Future Facility with Kim Colin in 2016. Sitting in the practice’s London studio, surrounded by working prototypes of security cameras and battery packs, Hecht tells monocle that both he and Colin felt that practical, human-centric product design had begun to give way to technology for its own sake. “It wasn’t that these were bad products – more that there wasn’t an understanding of the potential of what they were working with,” he says. “That’s where Future Facility came in.”

The company, which sits at the intersection of product design and technology, began as a complementary practice to Industrial Facility, a furniture-focused studio that Hecht and Colin founded in 2002 whose portfolio includes work for the likes of MillerKnoll, Mattiazzi, Santa & Cole, Muji and Emeco. By contrast, Future Facility set out to research, invent and prototype products that bring humanity to technology. “The way that engineers and industry experts imagine the potential for their products usually has very little to do with how we’re actually living with things,” says Colin. He adds that Future Facility’s way of addressing the aforementioned loopiness was to take technology off its pedestal and put it on level terms with a piece’s form and function.

It’s an approach that Leo Leitner helped to define when he joined Future Facility in 2021. The German-born designer is the firm’s creative director. “Big companies often try to make something that sounds technologically innovative but their products don’t actually bring a lot of benefits to the user,” he says. As an alternative, he points to an AI companion device that the firm developed with Taiwanese computer and electronics company Asus. Called Susa, it allows users to load maps, share photos, take phone calls and more. Its digital screen is hidden behind a perforated, tactile frontage made from Ceraluminum (fused ceramic and aluminium, specially developed by Asus), creating a deliberately low-resolution haptic surface. “This product was about saying, ‘You can do all of the things that you normally do on your phone but the screen is going to be lower resolution,’” says Hecht, explaining that the team wanted to reduce the appeal of glowing pixels and counter the overstimulating effect of a conventional screen, while also showcasing the beauty of the device’s materials.

The project sums up Future Facility’s ambition – one that places users and their needs at the heart of its product and technology design. (In Susa’s case, one goal was to help people to cut back on screen time.) “In our everyday lives, we don’t think of a chair any differently to how we think about our phone – both are part of our environment and the way we live,” says Colin. “What we do at Future Facility is think across product design and technology, and integrate them.” — futurefacility.co.uk

Of all the people to become Uniqlo’s first global creative director, British fashion designer Clare Waight Keller wasn’t perhaps the obvious choice. Her CV is more haute than high street, including working for Gucci in its Tom Ford heyday and leading the revival of Parisian label Chloé. After leaving her last post as creative director of Givenchy in 2020, she took a two-year pause to reflect on the future of fashion and her own place in the industry. She concluded that there was more to learn by working with a Japanese high-street giant than another European luxury house. After spending time in Tokyo to work on a collaboration with Uniqlo (the now bestselling Uniqlo:C line), she began to imagine a bigger remit with the brand, and her new job announcement followed in late 2024.

“I have been thinking about where fashion will go in the next 10 to 15 years,” says Waight Keller, who is now based between southwest London and Uniqlo’s head offices in Tokyo. “Where I see the most interest and growth is in Asia.” Wrapped in a cosy, grey coat from her Uniqlo:C line, her eyes light up when she speaks about the advances in hospitality, architecture and fabric development that she has discovered during her travels.

As luxury becomes more mainstream, Waight Keller believes that there are new opportunities for high-street brands to improve on quality and design to reach customers looking for value rather than status. Here, she shares her plans for 2025.

Why choose Uniqlo instead of returning to luxury?

I’ve always taken quite surprising moves in my career. Over the past decade or two, many people have said to me, “Oh my God, I didn’t expect to see you there.” But that’s part of what I search for: the surprise, the challenge. As a designer, it’s very easy to do the same type of job under a different umbrella. That might be a great career move but it’s familiar. I’m only on this planet for a short amount of time, so I just want to make it as interesting as possible.

I spent a lot of time in Tokyo working with the team on my collaboration collection. During that time, I was getting involved in a lot of the meetings and discussions, so we started thinking that this could be a bigger opportunity. The brand itself is so well-loved and it is one of the few brands on the high street that’s also known for innovation. That for me was the big draw.

What are the opportunities and challenges of working at a bigger, better-known brand?

One designer I got to know really well when I was living in Paris was the late Karl Lagerfeld. I always admired his chameleon-like approach to working for different brands such as Chanel, Fendi and Chloé. I admired the fact that he morphed every time. He was one of those designers who tried to immerse himself in the storytelling of the brand and to bring his own flavour to it. I’m the same way: I’m not a designer who imposes my look on a brand. With certain designers today, you know what you’re getting when they move and that’s reassuring for a lot of people. But I like immersing myself in the story of the house and trying to thread a new chapter. It’s not my chapter; it’s the company’s chapter. The company will be around much longer than I will, so for me it’s about translating that and making it relevant to the moment.

Why is this company-first design approach so rare?

It’s partly because of the lack of women in our industry. Women have a different approach and a different way of designing; it’s very customer-centric in that sense. I know people don’t think customers are sexy to talk about but ultimately they are the people who buy your product. Just having a model as your only idea of the true vision of your brand? Sorry, but I find that very limiting.

How has your approach changed since you started working on your first collaboration with Uniqlo?

It has changed vastly. I’m suddenly seeing my jacket in a full range of sizes and I want to make it look amazing in every size, so I might add some shape on the upper back or a little more hip volume. Otherwise, it’s lazy design. As a designer, you need to adapt; you have an ability to create and be thoughtful about the product you’re using. It’s the same when someone is designing a chair: they need to think about the different people who will sit on it, about supporting the back or getting the dimensions correct so that the legs aren’t floating around. You have to find solutions to problems and do it beautifully.

What changes should we expect to see on Uniqlo shop floors in 2025?

I oversee everything except for the childrenswear. All the menswear, womenswear, all the socks – everything that you regularly see in a Uniqlo shop is now part of my design remit. The biggest change you’ll see is definitely colour, which is something I’m working on constantly, even on those classic lines we rarely touch. This season, for instance, there’s the new cashmere palette and I selected every one of the 50 shades. Then there’s the new seasonal shapes: new trouser silhouettes; new ultra-light Blocktech jackets; and a new Puffertech coming in. We’re also trying to introduce recycled programmes as much as possible – our biggest issue is actually people not donating enough, if you can believe it. So anyone who has any extra nylons or downs, please bring them to a Uniqlo shop and we’ll make you a new one.

A lot of luxury customers rely on Uniqlo for their basics. Is our definition of luxury changing?

I see people dressing both high and low. A lot of luxury is unaffordable and that’s a challenge for many people who love fashion. There is, of course, the secondhand market but there is a real need for those really well-made, well-priced value pieces such as the Uniqlo Airism T-shirt or the cashmere jumpers. I’ve been buying Uniqlo cashmere for 10 years and it’s a great product. It lasts so long – all you need to do is maybe add a new colour or a slightly different proportion. It’s a new way of looking at brands.

There’s also an interesting shift with the high-street brands trying to raise the bar in terms of their image and the people they collaborate with, including photographers and stylists. There’s less discrepancy in image between high street and luxury. Maybe there’s still some when it comes to quality but it depends on how you put it together. I genuinely look at a lot of the Uniqlo products – like a fully unlined, tailored jacket – and I can’t believe how high the quality is. It’s because of the high standards Uniqlo abides by, the attention to detail and the precision it puts into things. It’s cultural, which is why, as a designer, it’s so amazing to work in Tokyo.

Is Asia now playing a bigger role in setting the global fashion agenda?

It’s interesting to look at what Asia is doing and realise there’s a lot of value in what it can bring to the table. I spent so much time in Western markets and Western companies, and we were always looking to the East but were never part of the East. There has been a blanket approach when it comes to Asia but it’s so vastly different and there are so many exciting developments happening across the continent. The general trope is cheap manufacturing, which isn’t true any more. There’s an understanding that’s really vast in terms of technology and the future; it is more open-minded and experimental because it has a comfort level with development. In Europe, we would probably be considered sleepier in the way that we approach things. Certainly, manufacturing is very slow. In Asia, the emergence of K-pop, K-beauty, the restaurant scene, the way cities are being developed, the architects working over there – it’s extremely dynamic.

What are your predictions for the broader fashion industry in 2025?

Coronavirus obviously created this massive growth spurt that everyone enjoyed tremendously but since then we’ve experienced this feeling of being on the crest of a wave. Sometimes you don’t see when it’s going to crash and fall because you’re on the wave. There needs to be some sort of adjustment and that comes with going back and understanding why people love that brand and why it should exist. These are the classic questions that you ask if you’re in brand marketing: why you’re there, what’s the reason behind what you’re doing and why would people buy it. But you should be able to answer those questions concretely. It’s not enough to just make a new T-shirt. There has been an era in fashion when just putting out a brand name was enough and that has certainly played out really well, but maybe we need to look back at design now and those reasons that are more intrinsic to why you want to buy a product and how it links back to a brand. Yes, there’s always going to be an element of status but, ultimately, people need quality.

These days, whether you’re trying to buy a designer handbag or a freshly baked croissant, you’ll probably end up waiting in line. Sometimes you’ll need to sign up via a QR code first; as soon as your time slot or appointment is over, you’ll be rushed off to make way for the next customer. Queueing culture is particularly evident in New York, where residents and visitors alike line up for everything from ready-to-wear ensembles on Madison Avenue to cookies from Soho’s Levain Bakery.

But not everyone is happy to wait and some are lamenting the loss of shops such as Barneys, Opening Ceremony or Odin. Luckily, a new generation of retailers is emerging to fill the gap, obviating the need for queues by doubling down on personal service and privacy: think by-appointment showrooms, one-on-one consultations and sharp product picks.

Among the leading figures of this new wave of retail experiences is former fashion buyer Dawn Nguyen. Last year she opened L’Ensemble, a multi-brand boutique in Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighbourhood. Crafted with interior designer Patrick Bozeman, the dimly lit space is furnished with mid-century pieces, such as chairs by Afra and Tobia Scarpa, and dotted with wood sculptures by Chandler McLellan. It already has a regular clientele of fashionable New Yorkers and a shopfront space is in the works for 2025.

“It was very difficult to find a place to shop,” says Nguyen, explaining what inspired her to start the business. “A lot of the multi-brand stores these days are either too hyped, too young or too mature.” So she set out to replicate the kinds of experiences that she would have when visiting brands’ showrooms for work. “As a buyer, you get to go behind the scenes and have conversations with extremely knowledgeable brand representatives,” she tells Monocle. “That allows you to learn the stories behind every collection. There’s so much intention behind the details. I thought that this type of experience should become part of everyday retail.”

L’Ensemble has no obvious signage. It’s set on a quiet cobbled street between residential neighbourhoods – a far cry from the bustling retail spaces across the East River. “It was tricky at first,” says Nguyen. “You have to work on strong marketing from the back end when you’re not getting any foot traffic.”

The shop’s intimacy reflects a broader appetite for one-on-one service and discretion that is increasingly shared by discerning larger-scale retailers and global luxury brands. Labels at the pinnacle of the luxury sector are turning to client dinners and money-can’t-buy experiences that are held behind closed doors. Many businesses are now investing in personal-shopping teams instead of influencer marketing, while some of the most exclusive members’ clubs ask visitors to stick a tape on their iPhone cameras before entering.

In a way, L’Ensemble has itself become a kind of private member’s club, with regulars booking appointments to shop for all of their special occasions. Consultations can be arranged in advance; after a quick chat, the team puts together a selection that’s tailored to every customer’s needs. Are privacy and discretion the new luxury? “Customers enjoy how everything is personalised,” says Nguyen. “And they’re not being rushed. It means that they can really get behind their purchases.”

Rather than following runway trends, L’Ensemble’s clothing selection responds to the specific needs of customers. Inside the showroom, you’ll find neat rails lined with brands that usually fly under the radar in New York: coats from Copenhagen’s Sunflower, for example, as well as sweaters from Amsterdam’s Extreme Cashmere and leather derbies from French brand Paraboot. There’s a strong vision here: someone has clearly thought very hard about every item. “I usually pick brands that make very wearable pieces,” says Nguyen, who initially studied menswear design at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology and finds herself drawn to unisex items. “Showcasing brands that don’t have much distribution is important to me.”

For Nguyen, displaying her finds in the right physical environment and being on the shop floor to meet customers are also crucial. “Things don’t really translate well online, especially with brands that are quite luxurious,” she says. “You’ve got to feel [the items] and see how they look in real life.” Nguyen is usually on hand when customers visit; she also personally responds to their emails. “Being on the ground is what I’m used to. I like talking to clients. A lot of people come in with a specific need. You have to speak to them and allow them to open up. You really need that connection with them.”

Exclusivity isn’t the priority here. Whether customers are seeking styling advice or simply want to have items waiting for them in a dressing room, Nguyen ensures that the mood stays relaxed. She also makes a point of offering pieces at a range of prices – from $90 (€87) T-shirts up to $5,800 (€5,660) trench coats. “Nobody is buying $5,800 trench coats every day,” she says. “It’s important to represent all levels. The store is for everybody.” It’s also why the shop is now introducing drop-in consultations that don’t need to be booked in advance. “We’ll make sure that we always have enough staff to take care of clients individually.”

L’Ensemble is preparing to move to a bigger, street-level Dumbo location later this year that will continue to offer one-on-one services. “People look for experiences and want to be in a place that’s thoughtful,” says Nguyen. “I don’t see myself as being in the business of fashion or retail. I’m in the business of hospitality.” — lensemble.us

“Whether you’re purchasing a luxury garment or a novel, it’s a personal, tactile experience,” says Javier Arrevola. The CEO of Spanish bookshop chain Casa del Libro is sitting behind his desk in the company’s headquarters on the outskirts of Madrid, dressed in a sharp grey jacket and navy chinos – appropriate attire for someone who strategised for luxury labels including Loewe for 25 years. Arrevola arrived at Casa del Libro in 2018, eager to apply his know-how from premium fashion to the books sector.

In Spain, big chains such as Fnac, which sell everything from books to music, and department stores such as the El Corte Inglés group are fierce competitors. So Arrevola has focused on creating a more personal retail experience and uses staff recommendations to help move titles. “It’s part of what I call the bookseller’s prescription and it’s a lesson that I learnt in fashion showrooms,” he says. “Our team of 1,000 booksellers don’t just see books as products. They see literature as a vocation.” Despite being a chain, Casa del Libro has developed a service that’s more akin to an independent bookshop.

But creating a more intimate experience for shoppers hasn’t limited Arrevola’s ambitions for the company. When he was appointed as CEO, Casa del Libro had 45 shops in Spain’s biggest cities, including Barcelona, Bilbao and Seville. Demand for physical shops has since risen: according to the Spanish publishers’ guild, bookshops generated nearly 55 per cent of the sector’s turnover in 2023. For all the talk of evolving consumer habits, bricks-and-mortar outposts remain crucial to the country’s book trade. Casa del Libro currently has 63 outlets, with seven more planned for 2025.

But it’s not just a matter of expanding to generate profit, says Arrevola. It’s also about the company’s longstanding penchant for print in all of its forms. Basque pro-democracy journalist Nicolás María de Urgoiti launched Casa del Libro in 1923. “The company was established in an era when bookshops displayed their wares behind glass as though they were untouchable objects,” says Arrevola. “At the time, about half of the population was illiterate,” he adds, explaining that being able to touch, hold and flick through the pages before purchasing a book was a novelty for many. “We have always sought to democratise the reading experience.”

But the meaning of democracy in Spain has shifted drastically over the chain’s decades of operation. In the dark days of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, the bookshop stuck to its founding principles and continued to play host to intellectual gatherings at its headquarters at 29 Gran Vía in Madrid – though these had to be held in secret at a time of repression and strict censorship.

Today the company’s dedication to democracy is reflected in Arrevola’s commitment to establishing outposts in Spain’s smaller cities. “We now reach Reus in Tarragona, Pontevedra in Galicia and Jerez de la Frontera in Andalusia and show that Madrid doesn’t have to be regarded as the epicentre of Spain’s literary prowess,” he says.

Some of Casa del Libro’s shops have sizeable nooks dotted around that encourage customers to settle down and read their chosen books, just like in a public library. As the publishing industry continues to enjoy an uptick across Spain (there was a 5 per cent increase in the sector’s turnover between 2022 and 2023), it’s a reminder that everyone deserves equal access to literature – whether you’re buying a book or returning one to the shelf.

Beyond Spain, in countries such as Peru, Colombia and Mexico, readers can consume Spain’s exported literary canon via the company’s dedicated Latin American website. “In that part of the world, the industry has succumbed less dramatically to Amazon than its European counterpart,” says Arrevola. Casa del Libro doesn’t have physical shops in Latin America – instead the focus is on online sales and virtual libraries. It’s a strategy that the brand committed to as early as 1996 and which Arrevola has implemented according to the demands of each individual market.

In Spain, however, the Amazon effect is more keenly felt. The e-commerce giant can offer more competitive prices than domestic businesses, which are limited by a 5 per cent discount cap. Nevertheless, Casa del Libro, which Spain’s leading publishing group, Grupo Planeta, acquired in 1992, has a home-turf advantage that Arrevola believes will continue to give it a healthy market share in 2025.

“We export to five continents but our DNA is Spanish,” he says, as he shows Monocle around the Gran Vía flagship. Arrevola points to books by the country’s writers of the moment – Julia Navarro, Eloy Moreno and Carmen Mola – who have tapped into Spain’s appetite for thrillers. “Coming to a Casa del Libro shop should feel as leisurely as going to the cinema,” says Arrevola. He believes that the experience of buying a book should be relaxed yet luxurious. Though much has shifted in Spain’s literary landscape since the shop was founded (even King Felipe VI attended the centenary celebrations in 2023), Casa del Libro’s commitment to a tangible reading experience remains resolute. The CEO’s enthusiasm for his retail empire is a reminder that books are more than just commodities – and that a bookshop can come with a happy ending.casadellibro.com

Casa del Libro in numbers

1923: Founded in Madrid

12 bookshops in the Spanish capital

5 continents to which Casa del Libro ships

36 Spanish cities with a Casa del Libro bookshop

About 75 per cent of sales are made in store

The Vatican and Saudi Arabia, home to the holiest sites of Catholicism and Islam, aren’t on the friendliest terms. As a result of past quibbles, the theocracies don’t even officially recognise each other. But on the long list of participants in the Islamic Arts Biennale (IAB), which runs from 25 January to 25 May, is a feat of diplomacy. In the event, which gathers masterpieces from across the Muslim world in Jeddah airport’s Hajj Terminal, there are 11 works shipped in straight from the Holy See.

Delio Proverbio, a curator at the Vatican Apostolic Library, says that this is a first both in terms of the recipient country and the size of the loan. “Even to an institution such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, we would lend a maximum of three works,” he tells Monocle But Proverbio was persuaded to collaborate by Abdul Rahman Azzam, one of the IAB’s artistic directors, and Aya Al-Bakree, the ceo of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation, the event’s organiser. It helped that the inaugural 2023 edition, which displayed ancient scientific instruments alongside newly commissioned artworks, had been a blockbuster success with more than 600,000 visitors. “The Pope himself said, ‘You have to join this exhibition,’” says Proverbio.

Last spring the Saudis visited the Vatican to peruse its archives. The star item that they chose for the show is a six-metre-long 17th-century map of the Nile. It was made by Ottoman-Turkish explorer Evliya Celebi, the author of the Seyahatname travelogue. “When I saw it, I was blown away,” says Al-Bakree. “We were all trying to see the little inscriptions.” The biennale agreed to fund a thorough restoration of the work.

Is this collaboration a sign of thawing relations between the two states? “That’s beyond all our pay grades,” says Al-Bakree. Even so, it’s a prime example of how cultural institutions can make space for tolerance and co-operation even, and especially, where politics cannot.

biennale.org.sa

Seoul’s Daeshin Wirye Center has a bookish new occupant with a distinctive mid-century style. Graphic, a library devoted to comics and art books, has opened its second branch here. The three-storey space is attracting crowds of people drawn by its immersive reading experience. For an entrance fee, visitors can peruse the collection and settle into any of its inviting nooks, cosy settees or veranda chairs, all while enjoying tasty snacks and drinks.

The idea is to allow readers to lose themselves in books and stay as long as they want – at least, up to a point (the high demand has led to the introduction of a three-hour cap at peak times). Graphic’s popularity reflects a growing appreciation of print media in a city known for its “snack culture” – the tech-savvy population’s habit of scrolling content such as webtoons in bite-sized chunks. It’s the latest addition to Seoul’s expanding array of sit-down reading sanctuaries, from the expertly curated, genre-focused Hyundai Card Libraries to Cheongdam’s membership-based Sojeonseolim Library, which hosts book clubs and author visits.

Whether it’s by encouraging readers to lounge on beanbags or by having a DJ set the mood, Seoul is reimagining how books are experienced. Pull up a chair and get stuck in.

graphicbookstore.imweb.me

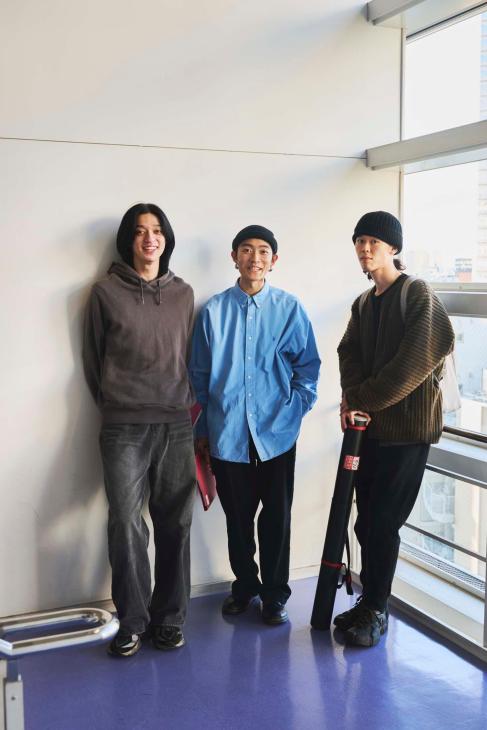

Anyone interested in finding out what ultra fashion- conscious young Tokyoites are wearing should take a seat in the canteen of Bunka Fashion College, Japan’s highly rated fashion school. As it turns out, the young bloods of Japanese style are wearing anything and everything: there are Lolitas in lace caps, anime-inspired goths and young fogies in jackets and ties. There are platforms, pearls, piercings, military jackets, hats with pointy equine ears, the odd designer label (worn ironically) and, of course, hair styled in myriad hues and cuts. At lunchtime, students wearing clothes that reference subcultures that nobody over the age of 25 can hope to understand huddle together. It’s a scintillating, frequently incomprehensible, parade.

Bunka’s alumni list is a dazzling who’s who of Japanese fashion, from Kenzo Takada and Yohji Yamamoto to Junya Watanabe, Jun Takahashi (Undercover), Nigo (of A Bathing Ape fame) and more recently, Ryota Iwai (Auralee), Maiko Kuroguchi and Shinpei Goto, whose label Masu is a student favourite. The college was founded by Isaburo Namiki as the Namiki Women’s and Children’s Dressmaking School in 1919. It became Bunka Fashion College in 1936, the same year that it began publishing So-en, Japan’s first fashion magazine (which is still going strong). Bunka started admitting men in 1957 (Kenzo was among the early intake). The current building, a vast edifice in Shinjuku, opened in 1998 and today there are 3,300 students learning about design, textiles, jewellery, styling, marketing, modelling, knitwear and many other aspects of the fashion business.

The big hitters emerge from the design course. Satoshi Morimoto is one of the teachers. The fashionable 30-something from Osaka with bleach-tipped hair is helping a student who is trying to upcycle a pair of jeans. “I want to teach the students to be disciplined but, at the same time, I hope that they can enjoy expressing themselves through fashion, have the freedom to dream up ideas and always be curious and willing to take on new challenges,” he says. One advantage of Bunka, he tells monocle, is its location in central Tokyo “where new things are constantly being created”. He says that it can be hard to spot the stars of the future. Some of the most successful have been the quietest students.

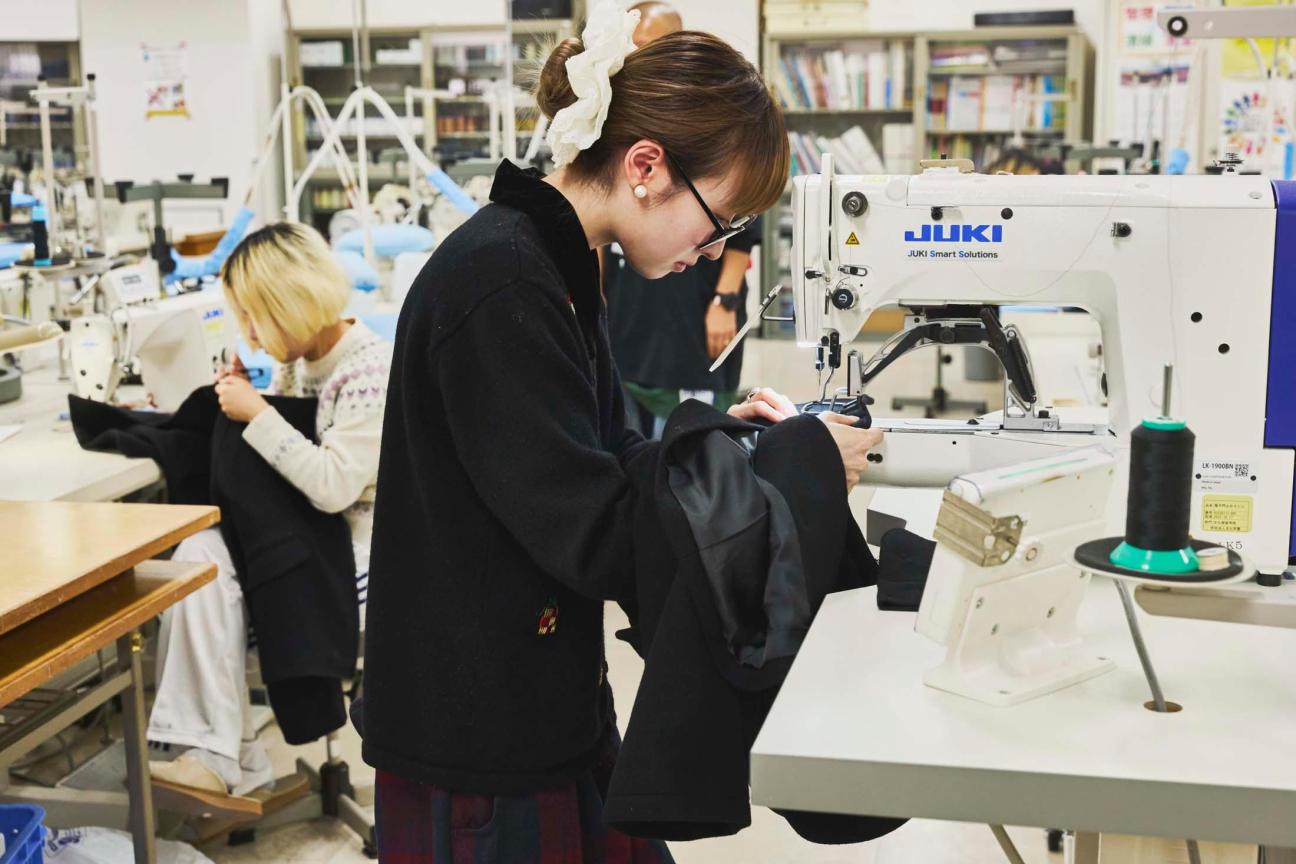

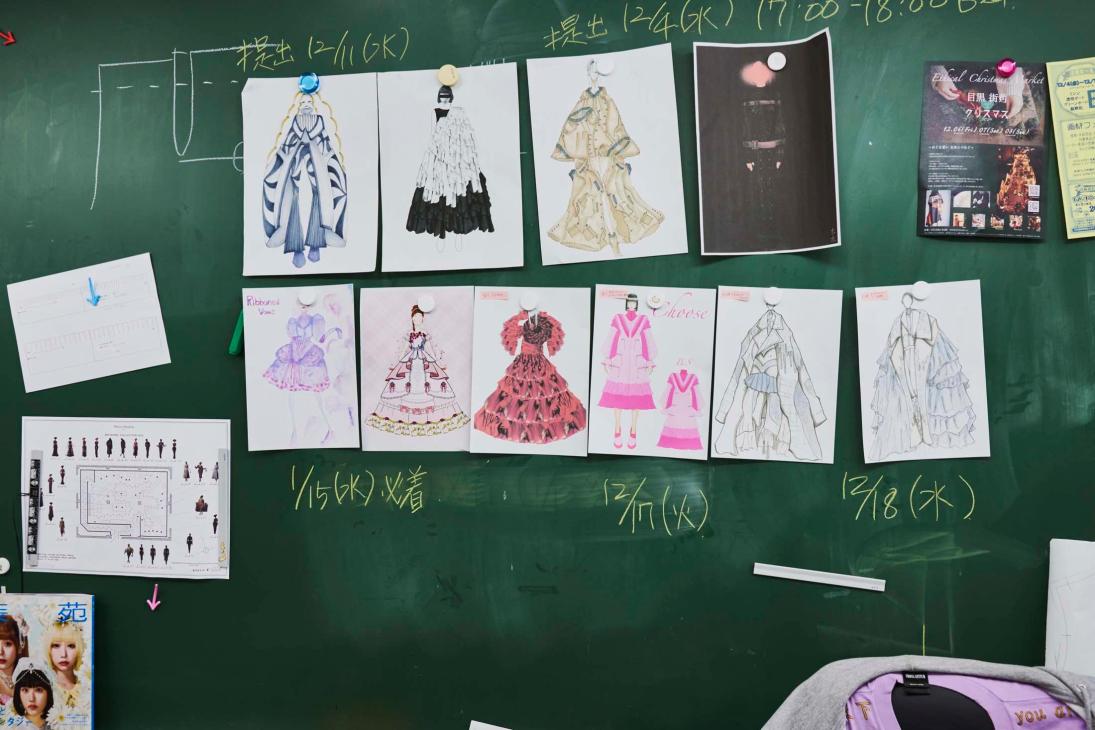

A visit to Bunka quickly reveals why Japanese designers are so technically skilled and prone to splicing fabrics at every opportunity – every design student has to master sewing and pattern cutting. No exceptions. In one classroom, a teacher is patiently going through the steps of making darts in a skirt. In another, a mannequin is draped in swaths of tulle. Morimoto says that the school’s technical teaching is a defining feature. “These pattern and sewing techniques have been passed down and developed for 100 years.” Computers play their part in Bunka but not at the expense of hands-on experience. The school even has its own fabric shop and another store selling all of the equipment that the would-be designer might need.

“It’s always about sewing and more sewing,” says one second-year undergraduate. What the students don’t always appreciate is that those skills will be what separates them from the rest. Just as the best abstract artists have put in the hours to master figurative drawing first, so these students will have all the tools that they need to de- and reconstruct any garment they choose. In the corridor of the design department, mannequins are clad in pieces that students have meticulously recreated from photographs.

The Bunka students Monocle meets rarely aspire to be the next Alexander McQueen or Rei Kawakubo. They seem to have little to no interest in famous names or even in fashion history. Nineteen-year-old Haruto Ogawa made a name for himself at his Bunka matriculation by printing a giant picture of himself on his trousers. He did the same with a bag and now gets requests via Instagram. A rebellious soul, he changes his look every day. Today he’s channelling the distinctive silhouette of a Japanese construction worker – slinky black top, balloon trousers (worn perilously low) and split-toed jika-tabi footwear.

You might think that the students here would be poring over style magazines and following the global fashion cycle but they’re more likely to be scrolling through Instagram or window shopping for obscure labels at The Four-Eyed select shop in Kabukicho. “I don’t follow famous designers,” says Ogawa. “I like niche brands from around Asia.” Notions of gendered fashion are out the window too. “It doesn’t matter anymore,” he says.

They might not be drawn to commerce but the average Bunka graduate is still likely to find gainful employment. Final-year creative design student Karin Tsujino already has stylists knocking on her door, clamouring to borrow her complicated candy-coloured tulle confections. She’s also dressing Japanese entertainers whose look is their strongest talent. Tsujino describes her work as “kawaii [cute] but not” and tries to explain the labyrinthine meanings of kawaii. Outsiders tend to think that it means saccharine and cutesy but kawaii can also be edgy and dark; even punk can be kawaii. Tusjino loves battle anime. “I want my work to reflect Tokyo culture,” she says. “It’s about Japanese music and anime as much as clothes.”

Final-year student Miu Beppu is wearing a hand-stitched parka by Keisuke Kanda (another Bunka graduate now making his name in Tokyo’s fashion world), knickerbockers and tassel loafers. She is part of a kawaii collective in Bunka called Ramb and already has a job lined up at a Kyoto lingerie company. Soon-to-graduate knitwear star Aiha Mori, who took up knitting during the coronavirus pandemic, is another member of Ramb. Mori’s been snapped up by a manufacturer that makes knitwear for top Japanese brands such as Sacai.

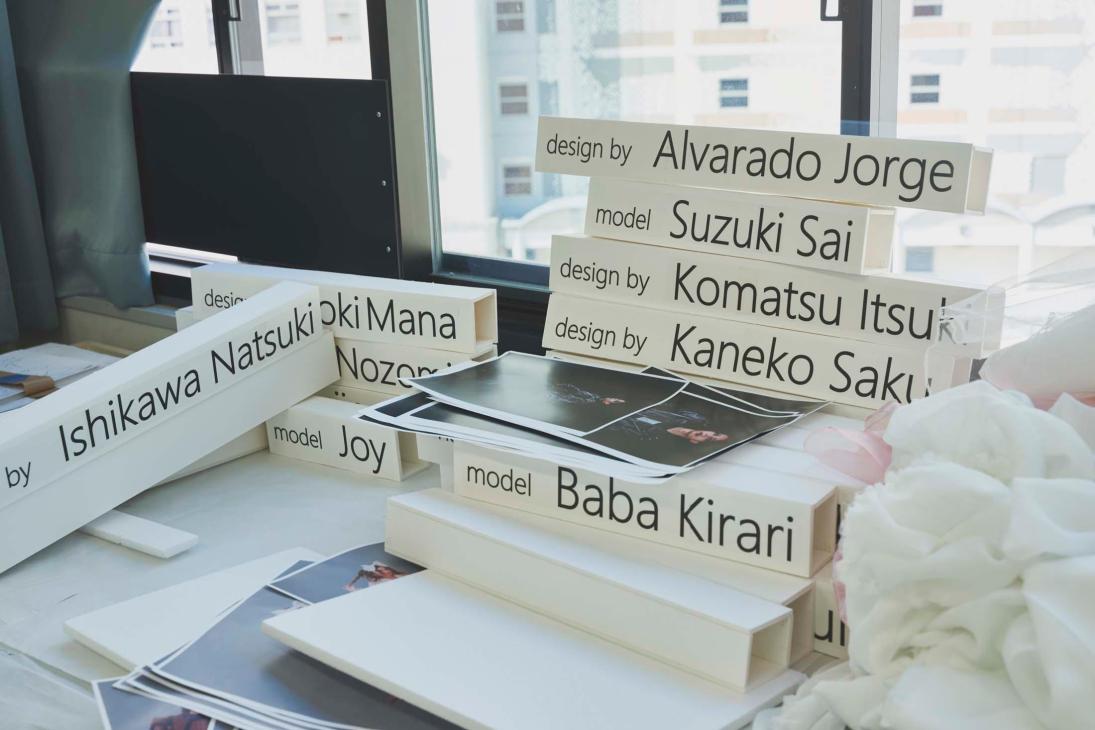

Every December the college hosts a fashion-design contest. The grand finale is a professional affair, with a proper runway and a pumping soundtrack. It’s standing-room only and the hall is packed with students and teachers. The finalists present one look each and it’s a big deal to take the top prize. Sera Kawasaki offers up a futuristic take on outdoor wear with a jacket and rucksack sculpted as a single piece, modelled by his friend, who stomps down the catwalk, hood up, shades on.

With his baseball cap and pearl earrings, Takumi Ogura has all the swagger of a model but is an aspiring second-year designer. His impressive lace construction is given life by his friend Mai Saito, who sways down the runway. At 27, Ogura is older than the average student and has an unusual back story. “I used to work in construction but I dreamt of being a fashion designer.” His background gives him a hunger; impatience even. “I don’t want to work for anyone else,” he says. “I want to set up on my own.”

The winner is William Cooke, a softly spoken student from Portland, Oregon, who has created a tailored leather two-piece inspired by bamboo craft and lacquer. Cooke is one of a cohort of international students who have to learn Japanese as well as the skills required to make it in fashion in Japan. He had spent a year in Niigata and decided to combine his interest in Japan and fashion by applying to study here. “Bunka is very different from other fashion schools in New York, London or Paris because the focus is on technique and sewing,” he says. “They don’t really teach you anything about design.” The students are different too, he says. “They’re not interested in collections, runways and designers; fashion is more of a lifestyle for them. I lean towards realistic, wearable clothing but at Bunka, fashion can be anything, your own fantasy.”

Adrienne Guilbaud, who is from Florida, says that the language, coronavirus and the compulsory sewing and pattern-cutting elements made the first year tough. “The Japanese spoken at Bunka is not the same as the Japanese I was being taught at school,” she says. “In the US, you might be going to college a couple of times a week but here it’s nine to five every day.” Guilbaud, who loves the Lolita style and draws inspiration from drag culture in Shinjuku’s Ni-chome neighbourhood, is loving Bunka now, thriving on its creative freedom. She is hoping to stay for a master’s degree. “Teachers here never say that a design is bad; they just tell you how to achieve it technically. The fashion market couldn’t be more different from the US. In Florida we all wear shorts and a tank top.”

For fashion references, teachers can go to the basement resource centre, run by head curator Tamiko Ueda. After nearly 30 years at Bunka, she has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the archive, which hangs on revolving racks according to type, including tracksuits, denim, eveningwear, garments made by students. The more precious pieces are curtained off: vintage Pierre Cardin, a solid collection of Kenzo pieces and an impressive section dedicated to “Swingin’ London”, stocked with psychedelic prints and Biba originals. There are 35,000 items (including hats, shoes and accessories) in the collection; the Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum is next door too.

Bunka has long had international connections. The first foreign student, Virya Chitinanda, came from Thailand in 1955 (the same year the school’s famous cylindrical campus building, now demolished, opened). Christian Dior, accompanied by seven models, held a show at Bunka in 1953; Pierre Cardin visited a couple of times and became an honorary professor in 1961. There have been European tours and tie-ups with colleges everywhere from New York to Shanghai. But the recent collapse of the yen, however, is making stints as colleges such as London’s Central Saint Martins or the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp out of reach for most Japanese fashion students.

A Bunka degree still opens doors in the Japanese fashion business. Some students, like Ogura, want to go it alone, while others follow other creative pursuits, such as floristry or photography. With true Japanese practicality, the college has a production department where students get to grips with something that Japan does exceptionally well: manufacturing. Guilbaud says that potential students from overseas are intrigued by Bunka, which is big in Japan but still has a low profile elsewhere. “I always say, if you want to make something classic like they would at Dior, then you should go to one of those other places, like Central Saint Martins. But if you want to learn how to make the things that you want to create, Bunka is the perfect school.”bunka-fc.ac.jp

The new headquarters of Finnish forestry giant Stora Enso is a tribute to the material that’s kept the company in business for 700 years. The largest timber building in Finland, Katajanokan Laituri is a fitting home for a firm that provides wood for the construction industry and turns trees into paper, packaging and, increasingly, biomaterials. “We are among the largest private owners of forests in the world,” says Hans Sohlström, the company’s CEO, who is sitting in one of the building’s soothing all-wooden meeting spaces overlooking Helsinki harbour. “Wood is at the heart of everything that we do.”

When Monocle visits the firm’s HQ, which opened in September, the public lobby is bustling with locals stopping in to take photographs of the new building and its airy atrium. Sweeping curves of exposed timber are illuminated by a large oculus-like skylight and the space is filled with the mild but pleasant scent of freshly cut wood. Employees gather over coffee here while the large terraces are perfect for a breather after business meetings, with the sound of waves lapping on the pier below.

The building, designed by Anttinen Oiva Architects, is constructed from more than 2,500 individually milled pieces of wood, from the laminated veneer lumber of the frame to the timber that lines the inner walls, lifts and staircases. There are trees planted in an open-air courtyard as well as in the expansive rooftop garden, which also features hammocks and a bar. All this, coupled with the building’s location, means that wherever you are in Katajanokan Laituri, your view is of wood and sea. “Being close to natural elements – so-called biophilic design – improves our wellbeing and productivity,” says Sohlström. “People are enthusiastic and inspired by working in this space. We’re already seeing more people wanting to return to the office, rather than work from home.”

It’s certainly an impressive building but the new HQ has a lot to live up to: Stora Enso’s former headquarters was a white, monolithic block designed by renowned Finnish architect Alvar Aalto and completed in 1962. It remains a landmark in the capital. The company’s new home, therefore, needed to be a striking piece of architecture but also express something about where the business is heading.

For much of its long history, Stora Enso was first and foremost a paper company. Since 2023, however, rising costs and falling demand have meant that Stora Enso is in the process of divesting from paper altogether. Paper now accounts for a small part of its overall revenue, even if the company still makes everything from newsprint to book and magazine paper, advertising paper and craft paper. “Paper as a product is not going anywhere and there is a great future for print media in specialised segments where digital cannot compete,” says Sohlström, kindly citing Monocle as his example. But packaging, he explains, has replaced paper as the primary driver of growth for the business. Just think of all those delivery services that we rely on. “There is a strong push to replace plastics in how we wrap products and the best way to achieve that is to use biodegradable wood-based alternatives.”

All of this is prompting the business to pivot. As it diversifies away from paper, Stora Enso is showing that wood from responsibly managed forests can be used to make many of the products that we need daily, such as tableware, cups, cosmetics containers, hygiene products and even cleaning products, in addition to packaging in its multiple forms. In part, this is about greater sustainability – putting fewer plastics derived from fossil fuels into the environment – but also a need for the company to move with the times. “Batteries, new types of construction materials, bio-based plastics,” says Sohlström as he lists just a few products derived from wood that Stora Enso has on the horizon. The company’s credo that “everything that is made from fossil-based materials today can be made from a tree tomorrow” is ambitious, perhaps even impossible. But every year a new product category is added that edges the industry closer to this goal.

Another sector in which the shift from fossil fuel-based materials to wood is making a significant environmental impact is construction. By using wood instead of concrete to build the new headquarters, Stora Enso says that it generated 35 per cent less carbon emissions during construction. That’s an area where the company sees the most growth potential in the years ahead. “In the EU alone, less than 3 per cent of all the material used in construction is renewable wood-based; the rest is almost entirely non-renewable,” says Sohlström. “In this way wooded construction can actually be a very important part of the climate solution.” Stora Enso’s new HQ embodies this thinking, he explains. “This building will store 6,000 tons of carbon for more than 100 years.”

Katajanokan Laituri and its meandering façade, reminiscent of Aalto’s signature waves and his iconic Savoy vase, occupies one of the most prominent locations on the Helsinki skyline. In the otherwise stone-clad neoclassicism of Helsinki, this wooden building is certainly a statement. It shows that Stora Enso, and by extension also Finland, are confident that wood has a bright future. Sohlström doesn’t deny the fact that the building was designed to impress. “We wanted to show what wood is capable of,” he tells Monocle. “This is a country that lives off of its forests.” — storaenso.com

Stora Enso in numbers

1288: Founded as the mining company Stora Kopparbergs Bergslag in Sweden

20,000: Number of employees

740,000 tonnes: Annual paper production capacity

20,000 sq km: Size of Stora Enso’s forests worldwide (about the size of Wales)

7,600 cubic metres: Amount of wood in new HQ