High-pressure design studios in Milan and Paris are at the heart of the fashion industry. But when temperatures rise, even the busiest designers choose to slow down, don swimwear and decamp to the Mediterranean – a pause very much encouraged by luxury Italian manufacturers’ religious commitment to the extended August break.

Brands have also been discovering that there are new ways to meet clients while lounging by the beach and have been embarking on a series of less expected, sunny collaborations with their favourite beach clubs, seaside hotels and even restaurants. Designers aren’t just creating exclusive summer collections for these destinations – they are now also custom-making parasols and sunloungers in their favourite shades or adding cocktails to a hotel’s menu. We round up some of our favourite fashion and hospitality tie-ins.

1.

Zeus+Dione

Lake Vouliagmeni

Athens

Legend has it that nymphs once inhabited the waters of Athens’ Lake Vouliagmeni, drawing unsuspecting men beneath its serene surface. A quiet pull endures today – one glance at the lake’s majestic landscape, framed by a large rock formation, lush greenery and glassy waters, is enough to lure you in. “When we visited the lake we saw the dramatic rock and the beautiful still waters,” says Dimitra Kolotoura, co-founder of Zeus+Dione, Athens’ flagship fashion label. “It started a fascinating design process for our creative director, Marios Schwab.”

Recently, the popular summer destination has become accessible again having been given a fresh look by creative consultant Athan Mytilinaios. Naturally, the Zeus+Dione team started spending more time in this corner of the Athenian Riviera, swimming in the clear waters or feasting on the seafood at Abra Ovata, the site’s Mediterranean restaurant. As a result, Kolotoura, Schwab and Mytilinaios joined forces to custom-design sunbeds, loungers, umbrellas and cushions for both the beach club and the restaurant. “Zeus+Dione is a custodian of Greek craftsmanship and a fantastic ambassador of Greek culture,” says Mytilinaios, explaining why it made sense to bring a fashion label on board.

Kolotoura is adamant that Zeus+Dione has never been a traditional fashion label so working with new mediums was part of the appeal. She tapped wood engraver Pantazis Tselios to create a one- of-a-kind motif that was printed on the sunloungers and umbrellas all around Lake Vouliagmeni’s beach club. “We’re used to working with people who have an ability to create with their hands,” she says, pointing to the intricate pattern, which pays homage to Byzantine art as well as the lake’s natural landscape. A closer look reveals details including rock, seaweed and Mediterranean flora carved into the wood. The finished pattern was then printed on durable technical fabric, used to upholster the club’s furniture. Lake Vouliagmeni formed naturally some 2,000 years ago when a cavern collapsed following an earthquake. It is now protected under the Natura 2000 network of conservation areas across Europe and its beach club differs from the traditional approach. “The place is about Zen and wellness, which is why we wanted to work with a brand that understands that good things take time,” says Mytilinaios.

For Zeus+Dione, the partnership offered a chance to tell its story away from the shop floor. “When someone visits the venue, they can discover how it aligns with our values and what we stand for,” says Kolotoura, who plans to unveil new phases of the collaboration next year. “Fashion wants to sell experience,” says Mytilinaios. “But there’s a limited number of experiences that you can offer if you only stay within your own realm.”

zeusndione.com; lakevouliagmeni.gr

2.

Louis Vuitton

Taormina cocktail bar

Sicily & Saint-Tropez

This summer, Louis Vuitton is diving deeper into hospitality by opening a series of culinary outposts around the Med. In the Sicilian town of Taormina, the French luxury house’s shop on Corso Umberto is opening its rooftop for guests to enjoy a cocktail at the new Le Bar Louis Vuitton. With views of the sea and the medieval town, the venue also offers contemporary takes on Sicilian classics courtesy of chef Dionisio Randazzo, who heads the nearby Nunziatina restaurant.

Meanwhile, in Saint-Tropez, the brand is once again taking over the White 1921 hotel. For the third year in a row chefs Maxime Frédéric and Arnaud Donckele are working together to infuse different cultural flavours in the menus. “Louis Vuitton is all about travel so the dishes have touches of Bangkok, France and Italy,” says Donckele. The result is a sun-soaked atmosphere in which French culinary excellence meets Mediterranean flavours, just a few steps away from the Louis Vuitton shop. “It’s a vibe: gastronomy with friendly service and music,” says Donckele. “We’re thinking about a lifestyle.”

louisvuitton.com

3.

CDLP

Hotel Passalacqua

Lake Como

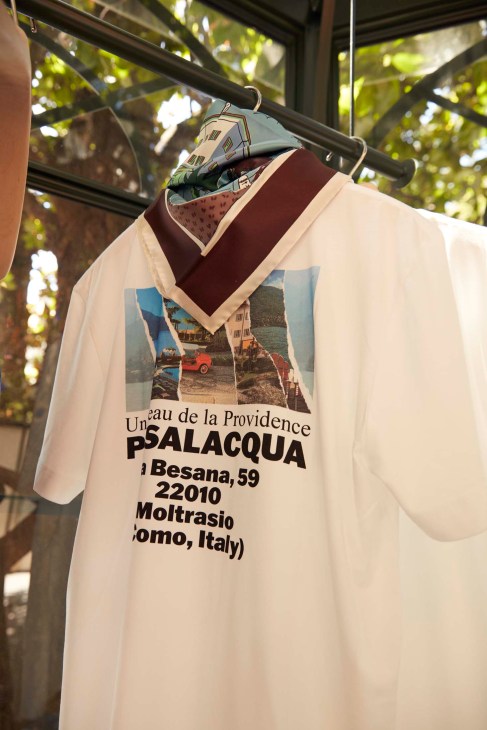

When Andreas Palm, co-founder of essentials and resort-wear label CDLP, first met Valentina de Santis, the CEO of Hotel Passalacqua, the pair were still students in Minneapolis. They couldn’t have predicted that, 20 years later, they would be sitting by Lake Como, orchestrating fashion and hospitality projects together.

Palm, who is based in Stockholm, began his career in hospitality and spent a few years organising guests’ trips to the Grand Hotel Tremezzo, the second Como hotel property belonging to De Santis and her family. When CDLP first ventured into swim and resort wear, it designed an exclusive capsule for the hotel. “This was before collaborations between fashion brands and hotels were so common,” says De Santis. “But we had so much fun. Andreas is so creative so I just follow his process.”

This summer the duo decided to continue the fun – and think bigger – with a fully fledged swim and resort-wear collection for men, which will be sold at the hotel’s boutique and on its e-commerce site, Sense of Lake. There’s also a sleek campaign featuring celebrated menswear stylist Robert Rabensteiner sporting the line. Think printed shirts inspired by vintage postcards, tailored swimming trunks made from recycled ocean waste and pool sets that can be worn for a relaxed sunset dinner. “If someone loses their luggage, they’ll find everything they need in this collection,” says Palm.

This type of tie-in might now be a lot more common in the worlds of fashion and hospitality but, for De Santis, there needs to be a personal story behind each project for it to be successful. “There isn’t really a strategy behind these collaborations, if I’m honest,” she says. “But each one has a lot of heart in it and, in this case, there’s a friendship behind it all. We don’t want to follow trends or create something according to guests’ expectations. The hotels are also our homes so we do what we love and aim to surprise our visitors. Giving a personality to a hotel and making people dream is important.”

Palm echoes her ideas, stressing that cultural value outweighs commercial motivation. “People are tired of collaborations that are just meant to drive sales,” he says. “It’s getting a bit boring. We want to work with people who we feel that we are aligned with in terms of values and aesthetics, and build something that will stand the test of time.” The eye-catching prints featured on some of the shirts and scarves in the collection are inspired by vintage postcards and represent quite a departure for the Swedish label, which is known for its understated aesthetic and monochromatic colour palettes. But to capture the visual richness of the Hotel Passalacqua, it was worth veering into new territory. “We always want to take things to a new level with this type of collaboration,” says Palm. “People are ready to go a little wild on holiday. You’re in a different mood if you’re in the Amalfi or Lake Como, rather than spending a regular Tuesday at home. It’s like stepping into a role – the holiday version of yourself.”

Our holiday selves also happen to be more willing to splurge, creating fertile ground for brands to meet new customers and encourage them to take sartorial risks. “A hotel director who I was speaking to called holiday spending ‘funny money’,” says Palm, who plans to celebrate the summer season and the launch of the collection with boat rides and long lunches with friends at the Passalacqua garden. “I think this is the most beautiful hotel in the world,” he says.

cdlp.com; senseoflake.com

4.

Jacquemus Jondal beach club

Ibiza

Born and raised in the south of France, designer Simon Porte Jacquemus is the fashion industry’s resident Mediterranean: always in favour of breezy linens, sunny stripes and dance parties that end at sunrise. The sun is inscribed in his eponymous label’s DNA and over time he has perfected the summer uniform with signature striped shirts, lightweight dresses and raffia handbags.

This year, to celebrate the arrival of warmer days, the Paris-based brand is leaving its home turf and flying to Ibiza – more specifically, to Casa Jondal on the island’s rocky southern coast. As part of a new, hospitality-focused collaboration, Jacquemus is fitting out the chic beach club with banana-yellow parasols and sunloungers that have playful polka-dot details echoing the brand’s spring/summer 2025 collection. Our favourite addition? An area reserved for playing pétanque, the French summer ball game par excellence.

Since founding his business in 2009, the French designer has been cleverly tapping into the power of sunny locations for his runway shows, inviting guests to Provençal lavender fields, modernist houses in Capri or art museums in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Extending this approach beyond the runway and into the realm of hospitality offers an opportunity to experience the label’s Mediterranean charm off-season too.

At Casa Jondal, you can spend the day under the club’s bright-yellow parasols, settle in for a sundowner with a tequila-based cocktail or enjoy signature seafood dishes such as fried squid, red prawn carpaccio and caviar.

You can also visit the temporary boutique on the beach and browse an exclusive resort collection of menswear, womenswear and accessories, including raffia hats and shirts featuring the same banana-yellow shade as the sunloungers. A series of novelty items including caps, keyrings and mugs double up as souvenirs of a beach holiday well spent.

jacquemus.com

5.

Ulla Johnson

Quinta da Comporta Carvalhal

New York-based designer Ulla Johnson has always embraced a sunny, bohemian spirit, no matter which season she is designing for. Her summer ranges in particular are filled with breezy dresses, lightweight broderie anglaise fabrics and elegant swimwear, inspired by Johnson’s travels and the artisan communities that she works with across the globe, in countries from Peru and Brazil to the Philippines.

This summer the designer is indulging her love of travel even further with a takeover that is soon to come to wellness resort Quinta da Comporta in Portugal during the first two weeks of July. The project includes ikat-print and hand-loomed robes and towels, which will be available for guests to use around the hotel and purchase at its boutique, alongside Ulla Johnson’s ready-to-wear range.

There’s also a new cocktail and health tonic concocted by Johnson – ideal for enjoying after a visit to the Oryza Spa or following a dip in the infinity pool.

ullajohnson.com; quintadacomporta.com

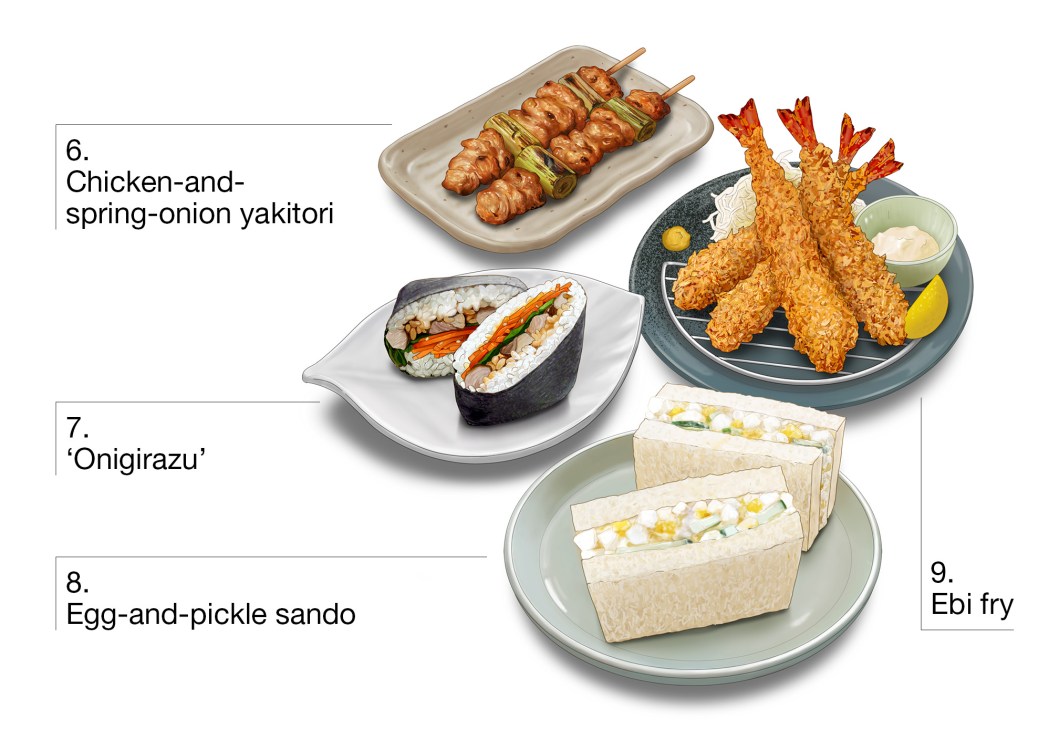

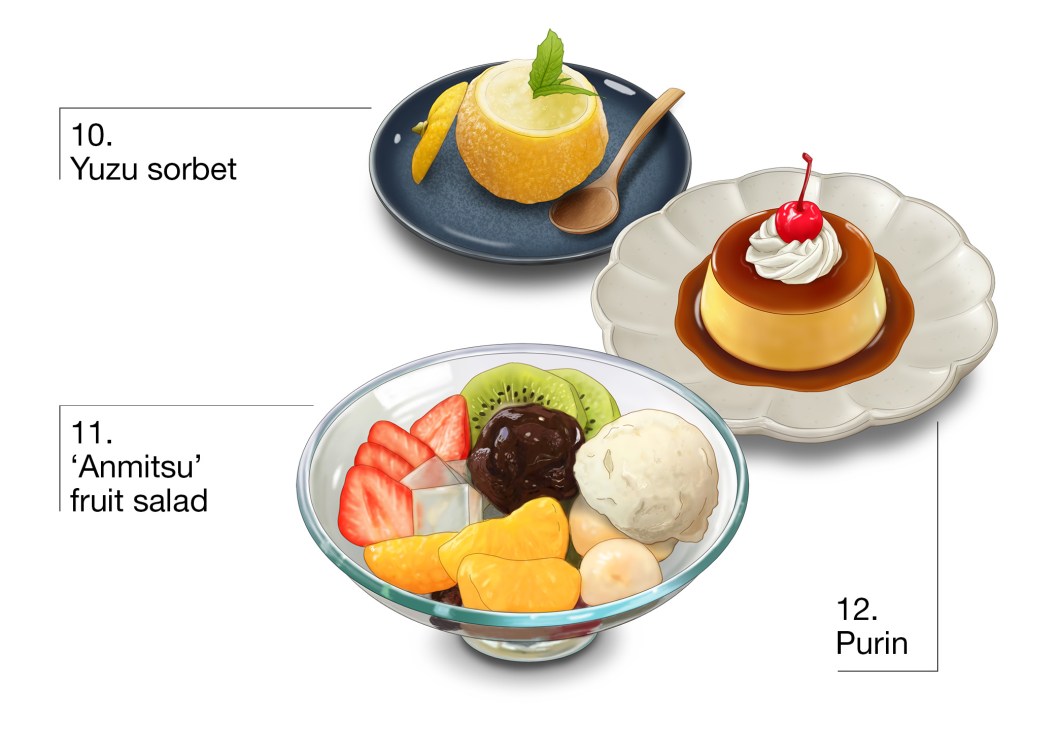

The arrival of the summer sun in the northern hemisphere means more eating alfresco. If you’ve got the weather, we’ve got the picnic line-up planned. With the help of Monocle’s Japan-born recipe writer, Aya Nishimura, we’ve popped together a plan for a fine open-air feast.

Our menu leans on well-executed comfort food in the yoshoku vein (Japanese, yes, but influenced by Western tastes and ideas). On our picnic blanket you’ll find rich yakitori skewers and an egg sando with a twist, alongside onigiri and crispy katsu prawns. For drinks, we’ve got you covered with a kitschy, refreshing melon-soda float – you’ll need a cooler for this one – and a refined shiso sour with plum for the grown-ups.

And if you’re new to Japanese cookery or feel daunted by what’s on offer, worry not. If you squint, most of our dishes feel rather like western dinner party dishes from the 1980s or picnic staples that you know, albeit with a few improving dashes of rice vinegar, some red-bean paste or yuzu kosho. Is that a crème caramel and fruit salad I see before me? There’s nothing to fear here but plenty to be gained from some simple, judiciously applied Japanese techniques. We’re here to help your summer-picnic plans – how you hamper them is up to you. Enjoy.

1.

Drink

Melon-soda float

Serves 1

Ingredients

3 tbsps melon syrup (Ideally the bright-green kind used for Japanese shaved ice, kakigori. If this isn’t available or lacks the classic colour, add a dash of green food colouring.)

150ml unsweetened soda water 1 scoop vanilla ice cream

1 tinned cherry in syrup or maraschino cherry

Ice cubes

Instructions

1.

Fill a tall, stemmed glass with ice cubes and pour in the melon syrup.

2.

Add the soda water and stir gently with a muddler.

3.

Top with a scoop of vanilla ice cream and place the cherry on the side.

4.

Serve immediately with a straw or a long spoon.

2.

Drink

Shiso umeshu sour

Serves 1

Ingredients

50ml umeshu (Japanese plum liqueur)

1 tbsp fresh lemon juice

1½ shiso leaves

Egg white from a medium egg

2 dashes Angostura bitters

Ice cubes

Instructions

1.

Blend the umeshu, lemon juice and a shiso leaf together until smooth.

2.

Add a few ice cubes to a shaker alongside the blended mixture, egg white and Angostura bitters. Shake vigorously until chilled and frothy.

3.

Strain into a glass filled with fresh ice.

4.

Slice the remaining ½ shiso leaf lengthwise and place it on top as a garnish. Serve immediately and enjoy.

3.

Side

Soy-marinated quail eggs

Serves 4

Ingredients

12 quail eggs

3 tbsps light soy sauce

3 tbsps water

1 tbsp sugar

1 clove of garlic, crushed (keep it whole)

1 tsp yuzu kosho paste

2 spring onions, finely chopped

For the topping

2 tsps sesame seeds

Instructions

1.

Bring a pan of water to a boil. Add the quail eggs and boil for 3 minutes. Prepare a bowl of ice-cold water and set aside.

2.

Transfer the eggs to the ice-cold water and cool for at least 5 minutes, then peel the eggs.

3.

Toast the sesame seeds in a dry pan over a medium heat until they begin to pop.

4.

Mix all the marinade ingredients in a bowl, until the sugar dissolves.

5.

Pour the marinade into a food-safe plastic bag or container. Add the peeled quail eggs and marinate for a minimum of 1-2 hours.

6.

Remove the eggs from the bag. Cut each egg in half and put them in a bowl with some of the marinade.

7.

Sprinkle with toasted sesame seeds and serve.

4.

Side

Daikon salad

Serves 4

Ingredients

For the dressing

2 tsps toasted sesame oil

1 tsp olive oil

2 tbsps rice vinegar

1 tsp light soy sauce

2 tsps honey

1 tbsp toasted sesame seeds

For the salad

200g daikon

1 spring onion

2g katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes)

1 large sheet of nori

Instructions

1.

Mix the dressing ingredients together in a small bowl. Set aside.

2.

Peel the daikon and slice it lengthwise, then cut it into thin matchsticks.

3.

Cut the spring onion into 5cm lengths, then slice thinly lengthways.

4.

Place the daikon and spring onion in a bowl of ice-cold water for 10 minutes to make them extra crisp.

5.

Drain using a sieve and pat dry thoroughly. Transfer to a serving bowl and refrigerate until ready to serve.

6.

Just before serving, drizzle the dressing over the salad. Sprinkle with katsuobushi, then crush the nori over the top and serve.

5.

Side

Potato salad

Serves 4

Ingredients

400g starchy potatoes, peeled and cut into 3cm cubes

1 tsp salt

75g cucumber

100g onion

1 egg

3 slices bacon, cut into 1.5cm pieces

2 tsps rice vinegar

2 tsps wholegrain mustard

3 tbsps Japanese mayonnaise

Black pepper, to taste

Instructions

1.

Cover the potatoes with water in the pan and add the salt. Boil, then simmer until soft. Drain, cool and roughly mash.

2.

Cook the egg in boiling water for 9 minutes, then cool in cold water. Peel and chop.

3.

Halve the cucumber lengthwise, remove seeds and slice thinly. Thinly slice the onion. Salt both lightly in separate bowls and let them sit to draw out the moisture. After a few minutes, squeeze and discard the excess liquid from the cucumber.

4.

Heat oil in a pan. Fry the bacon until crispy and drain it on a paper towel.

5.

Add the vinegar, mustard and mayo to the mashed potatoes. Mix in the chopped egg, squeezed cucumber, onion and most of the bacon.

6.

Top with the remaining bacon and freshly ground pepper.

6.

Main

Chicken and spring onion yakitori

Makes 9

Ingredients

For the chicken

500g skinless chicken thighs, cut into 3cm cubes with the fat removed

5 spring onions, cut into 4cm pieces

2 tsps sunflower oil

For the yakitori sauce

50ml soy sauce

1 tbsp mirin

1 tbsp saké

2 tbsps clear honey

Instructions

1.

Place all the sauce ingredients into a small pan and cook over a medium heat. When the sauce starts to boil, turn down the heat and simmer for five minutes or until the sauce has slightly thickened. Take the pan off the heat and leave to cool.

2.

Soak the bamboo skewers in water while preparing the ingredients (this is to prevent them from burning). Spear the chicken and spring onion with skewers, aiming for a good mix of chicken and spring onion.

3.

Heat a frying pan with the oil. When the oil starts to sizzle, place the chicken skewers in the pan. Cover and cook for 3 minutes on each side. Remove the lid. Char for 1 minute on each side, pressing with a spatula.

4.

Pour half of the yakitori sauce into the pan, turn the skewers with tongs and toss the sauce over the chicken. As the sauce thickens, take the pan off the heat.

5.

Arrange the skewers on a serving plate, drizzling them with the leftover cooking sauce.

7.

Main

‘Onigirazu’ (Rice sandwich)

Serves 4

Ingredients

For the ginger chicken

1 tbsp oil

20g ginger, cut into thin matchsticks

4 small chicken thighs, sliced into thin strips

3 tbsps light soy sauce

3 tbsps runny honey

For the sesame carrots

1½ tbsps toasted sesame oil

1 large carrot, peeled and cut into matchsticks

¼ tsp salt

1 tsp toasted sesame seeds

For assembling

4 sheets of sushi nori

150g Japanese rice

4 gem-lettuce leaves, washed and dried

Instructions

1.

Rinse the rice in a fine sieve under cold water. Soak in fresh water for 20 minutes, then drain.

2.

Place the rice in a medium cast-iron pan with 165ml water. Cover tightly and bring to a boil. Once you hear bubbling or see steam, reduce the heat to low and cook for 10 minutes. Turn off the heat and let the rice steam, covered, for another 10 minutes.

3.

Fluff the rice with a wet wooden spoon to prevent it from sticking, then re-cover until ready to use.

4.

Prepare the ginger chicken. Heat the oil in a frying pan, add the ginger and cook for 2 minutes. Add the chicken and cook until the colour changes. Stir in the soy sauce and honey. Cook until the chicken is coated and cooked through. Set aside.

5.

Prepare the sesame carrots. Heat a teaspoon of sesame oil in a pan, add the carrot and stir-fry for 1 minute. Turn off the heat, then stir in the remaining sesame oil, salt and sesame seeds. Set aside.

6.

Assemble the onigirazu. Place a sheet of clingfilm on a chopping board and lay a nori sheet on top. In the centre, spread 50g of cooked rice into a 10cm square. Layer with carrots, lettuce, then chicken. Finish with another layer of rice.

7.

Fold all four corners of the nori toward the centre, overlapping slightly to enclose the filling completely. Wrap tightly in cling film and let sit for 10 minutes to set.

8.

Cut the onigirazu in half horizontally. Remove the clingfilm and serve.

8.

Main

Egg-and-pickle sando

Serves 2

Ingredients

For the filling

3 medium eggs

45g takuan (pickled daikon)

1½ tbsps Japanese mayonnaise

½ tsp caster sugar

1½ tsps milk

1 tbsp chives, finely chopped

For the sandwich

4 slices of medium-thick soft white bread

20g unsalted butter, softened

1 tsp Dijon mustard

¼ cucumber, seeds removed

Instructions

1.

Bring a pot of water to a boil. Gently lower the eggs into the water, then reduce the heat to medium and cook for 8 minutes. Prepare a bowl of ice-cold water and set aside.

2.

Drain the eggs and place them immediately into the ice-cold water. Let them cool for 10 minutes, then peel.

3.

Roughly chop the eggs into 1cm pieces. Chop the pickled daikon into 5mm pieces.

4.

In a bowl, combine the eggs, pickled daikon, Japanese mayonnaise, sugar, milk and chives. Mix well.

5.

Spread the softened butter and a thin layer of Dijon mustard onto one side of each slice of bread.

6.

Spoon the egg salad evenly onto two slices of bread, leaving a 5mm border around the edges.

7.

Thinly slice the salted cucumber and arrange the slices over the egg salad.

8.

Top each slice with the remaining bread (buttered side facing down) and press.

9.

Trim the crusts, then cut each sandwich in half and serve.

9.

Main

Ebi fry (prawn katsu) with ‘shibazuke’ pickle tartar sauce

Serves 4

Ingredients

For the tartar sauce

4 medium eggs

½ large shallot, finely chopped

90g shibazuke pickles, chopped

1 tbsp shibazuke pickle juice (rice vinegar also works)

4 tbsps Japanese mayonnaise

Salt and pepper, to taste

For the prawn katsu

12 large prawns, shelled with tails intact, deveined

10g plain white flour

1 small egg, beaten

50g panko breadcrumbs

Neutral oil, for deep frying

Instructions

1.

Boil the eggs for 8 minutes, then cool them in ice water.

2.

Peel and chop the eggs into roughly 5mm pieces.

3.

Finely chop the shallot and shibazuke pickles into roughly 3mm pieces.

4.

Mix the chopped eggs, shallot and shibazuke with mayonnaise and pickle juice in a bowl.

5.

Season with salt and pepper. Set aside in the fridge until ready to serve.

6.

Turn the prawn over so that the belly (ventral side) is facing up. Make 4 or 5 shallow diagonal incisions along the belly, head to tail. Then hold both ends of the prawn and gently twist, stretching it until the internal muscle fibres snap, before straightening to prevent curling during cooking.

7.

Dust each prawn with flour, dip in the beaten egg and coat with panko.

8.

Heat the oil in a deep pot to about 180C.

9.

Fry the prawns in batches until golden and crispy. Drain on paper towels.

10.

Serve immediately with a generous spoonful of the shibazuke tartar sauce.

10.

Dessert

Yuzu sorbet

Serves 6

Ingredients

6 yuzu fruits (or small oranges)

85g granulated sugar

200ml water

2 tbsps yuzu jam

30ml yuzu juice

Instructions

1.

Slice a thin layer off the top and bottom of each yuzu (or orange) so that they sit flat. Cut off the top quarter horizontally and set the “lids” aside.

2.

Place a fine sieve over a bowl. Carefully squeeze the juice from each fruit through the sieve, making sure not to tear or break the skins. These will be used as serving cups.

3.

Using a spoon, scoop the pulp and membranes from three of the fruit bottoms. Take care not to pierce the skin.

4.

In a small saucepan, combine the sugar, water and yuzu jam. Bring to a simmer, stirring until the sugar dissolves. Remove from the heat. Let cool.

5.

Stir in the yuzu juice.

6.

Pour the mixture into a shallow metal tray and freeze for 2 hours. Once it starts to solidify, use a fork to break up the ice crystals.

7.

Repeat every hour, until the sorbet is light and fluffy.

8.

Scoop the sorbet into the yuzu shells, cover with the reserved lids and freeze again until ready to serve.

11.

Dessert

‘Anmitsu’ fruit salad

Serves 4

Ingredients

For the kanten (agar) jelly

375ml water

1½ tsps agar flakes

For the ‘kuromitsu’ syrup

100g dark muscovado sugar

100ml water

For the ‘anmitsu’ fruit bowl

300g tinned mandarin segments

2 kiwis

6 strawberries

4 tbsps adzuki-bean paste

4 scoops vanilla ice cream

Instructions

1.

Stir the agar flakes in 375ml water and soak for 30 mins (or follow the packet instructions). Pour the liquid and agar into a saucepan and let it heat without stirring. Once boiled, reduce to a simmer and cook for 5-10 minutes until it dissolves completely, stirring from time to time. Pour the liquid into a shallow metal tray and let it set in the fridge for about an hour.

2.

Put the sugar and water in a small pan and cook over a medium heat for 4-5 minutes, stirring occasionally until the sugar dissolves and the liquid thickens. Set it aside to cool.

3.

Once the kanten jelly is set, divide into 1cm cubes. Drain the mandarin segments and cut the kiwis and strawberries into bite-sized pieces.

4.

Divide the kanten jelly and fruit between four small bowls, adding one scoop of adzuki paste and vanilla ice cream to each. Drizzle with the kuromitsu syrup before serving.

12.

Dessert

Purin (Caramel pudding)

Serves 4

Ingredients

For the caramel

5 tbsps granulated sugar

2½ tbsps cold water

2½ tbsps hot water

For the custard

225ml whole milk

75ml double cream

60g caster sugar

3 medium eggs

1 medium egg yolk

½ tsp vanilla essence

To serve

Double cream, whipped

4 tinned cherries, in syrup

Instructions

1.

In a small saucepan over medium heat, combine the granulated sugar and cold water. Have hot water ready on the side. Once the sugar has melted, turning the mixture dark brown, remove from heat and carefully add the hot water all at once – it will bubble vigorously. Stir it gently to combine.

2.

Once the caramel has cooled slightly, pour it evenly into 4 ramekins.

3.

Preheat the oven to 140C.

4.

In a saucepan, heat the milk, cream and caster sugar until the sugar dissolves. Then remove it from the heat.

5.

In a bowl, beat the eggs and extra yolk together. Gradually add the warm milk mixture to the eggs, whisking constantly to prevent curdling.

6.

Stir in the vanilla essence. Strain the mixture through a sieve for a smoother texture.

7.

Divide the custard mixture evenly between the caramel-lined ramekins. Tightly cover each ramekin with foil.

8.

Line a deep baking tray with a kitchen cloth and place the ramekins on top.

9.

Pour hot water (50-60C) into the tray until it reaches halfway up the sides of the ramekins.

10.

Carefully transfer to the oven and bake for 20 minutes.

11.

Remove the ramekins from the tray and take off the foil. Give each ramekin a gentle shake; the custard should wobble slightly in the centre.

12.

Let them cool on a wire rack, then chill in the fridge for at least 2 hours.

13.

Run a knife around the edge of each ramekin to loosen the pudding inside. Invert onto a serving plate.

14.

Pipe a small amount of whipped double cream on top. Top with a cherry in syrup and serve.

Illustrator: Xiha

When did planes get so filthy? If passengers don’t hand over their garbage to the crew before landing, then all the pressure falls on a cleaning team that’s given just minutes to prepare an aircraft for its next journey. It’s why instead of having an engrossing book and toiletries in your carry-on, it might be wiser to take a duster and a miniature vacuum cleaner with you.

On a flight from Verona to London on Monday – and look at me all swanky in business class – the seat was crisp-strewn, the packet still in situ, the front pocket filled with empty drink cans. This is so commonplace that crews rarely apologise, they just take the rubbish from you without comment – it’s how life is now my dear.

You should be especially attuned to the potential need for a garbage-picking shift when you go on a long-haul journey. I recently found an apple core in an in-flight sock in my spot (a chocolate on my pillow would have been preferable) and, when I went looking for a dropped pen lid under my seat, I discovered a lost world of teaspoons, salt sachets and enough crumbs to bread a schnitzel. But there’s a bigger thing going on here – the failure of industrial design.

I went to a talk last year where an architect spoke about the potential touchpoints between cutting costs and doing good. For example, in say a hospital or industrial building where there will be tiled surfaces, he works out well in advance how to cover a wall without any tiles being cut (saves time, no wastage, good for the environment). But he also talked about something else that I now realise is vital – getting cleaning crews in at an early stage. Where will they keep their floor-buffing machines, their brooms? And, more importantly, will they be able to keep this space spotless without resorting to cherry-pickers or days of scrubbing?

I wonder how many times the makers of airline seats, the bosses of airlines, have emptied out packets of crisps on a new design, dropped a spoon (and a phone or two) into its recesses and asked a cleaning crew what they make of this contraption. Can they clean it in the seconds that they are given? In the meantime, if you don’t want to sit in an update of Tracey Emin’s bed, don’t forget to have Mr Sheen as your travel buddy next time you fly.

And Verona airport. It used to be cramped and a bit chaotic. Now they have lavished millions on a new terminal – and it’s charmless. The new infrastructure is part of the preparations for the 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Olympics (this will be a key gateway) and, admittedly, it’s not all finished but you have to hope that it’s going to move on from its current blandness. Simple design details seem to have been forgotten. The plaster on the corners of walls, for example, has already been knocked off to reveal the metal framing underneath. Did the architects ask the building-maintenance crew for their advice?

Sometimes things go awry because of badly managed value engineering and poor designs – but worthy legislation is also to blame. Apart from turtles, does anyone actually like the screw cap being tethered to a bottle? I’m not bothered about how they scrape your nose. My issue is that they don’t work. They show signs of incontinence – bottles leak in bags if you attempt reattaching said linked lid. Or they flip position mid-flow, causing liquid to dribble down shirts. I’m sticking to bottles of rosé with corks this summer as I take a stand on this issue.

But there are some things in life where design is all. The perfectly planned wedding last weekend in Lana, Südtirol, of two former colleagues who met at Midori House (thank you, Nolan and Hyo). The hotel that we stayed in, Villa Arnica, where every element was considered and precise, restrained and beautiful. The sets at the Kylie Minogue concert on Tuesday. The book, The Anthropocene Illusion, by the photographer Zed Nelson, which I finally saw at a launch on Thursday (we previewed this amazing project in The Forecast). All moments when someone thought about how people would feel in a space or as they turned a page. Moments when good design won the day.

“Enter here all who welcome sitting in the dark without hope,” reads the sign. It may sound uninviting but it turns out that film lovers are happy to do just that. Los Angeles-based non-profit American Cinematheque has expanded its Bleak Week: Cinema of Despair series beyond Hollywood, where it began in 2022, to seven additional locations across the US and internationally to London.

Bleak Week, which showcases films several shades right of noir (but left of horror) was born in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. “We felt that there was a generation of children watching Marvel movies who wanted more,” says Grant Moninger, American Cinematheque’s artistic director. “There are so many films selling spectacle, beauty and fantasy. But when we put this out there, people got it. It touched on more universal truths.”

More than 100 films will be shown across 10 theatres (American Cinematheque itself runs three across Los Angeles), ranging from the utterly brutal Behind the Door, a 1919 silent war drama from foundational Hollywood producer Thomas Ince and director Irvin Willat; to the plaintive, though less harrowing, Moneyball, starring Brad Pitt. The programme highlights great filmmaking that is raw – oftentimes ugly – and whose hard-to-watch nature means that its artistic merit is frequently overlooked. “There is something about an uncompromising approach to showing the dark side of human existence that becomes great art,” says Chris LeMaire, the organisation’s senior film programmer. “These are great films that resonate powerfully with audiences.”

As part of the festival’s expansion, London’s Prince Charles Cinema will be taking part for the first time this year. “As filmgoers and cinephiles, we’re drawn to [darker themes] at some point,” says Paul Vickery, Prince Charles Cinema’s head of programming. “We get to step into a world that we never want to be in.” Guest hosts will include The Brutalist filmmakers, Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold, who will be speaking before a showing of Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia; director John Hillcoat, who will present his gritty outback western, The Proposition; and The Northman auteur Robert Eggers, who will introduce Andrzej Zulawski’s The Devil. Bleak Week’s exploration of the underdog also includes animation and, of course, the classic heart wrencher, Watership Down. Each theatre is given free rein on which movies to show and the only rule is no documentaries.

Spoiler alert: there are no happy endings in bleak cinema. “There are rarely happy beginnings or happy middles,” says Vickery. But as Bleak Week attests, that’s not always what we want. “Personally, I find it appealing to lock myself in a dark room with people and sit through a moment that I hope I never have to actually experience,” he says. If the art of cinema imitates life, then what does our eagerness to consume such grim tales say? Instead of looking for a fairytale outcome, the relentless brutality of Bleak Week is a reassuring wake-up call.

bleakweek.com

“Our participation [in Milan Design Week] has a romantic origin,” says Eleni Petaloti, one half of New York and Athens-based Objects of Common Interest. “I always complain about us Greeks not being able to be ambitious together. So it was very important for me, psychologically, to be a part of this.” The Thessaloniki-born architect and designer, who runs the studio with her husband, Leonidas Trampoukis, is talking about the pair’s project in Milan this year at Alcova’s Pasino Glasshouses, entitled “Soft Horizons”. Featuring Greek marble from seven different companies with quarries around the country, from Athens to Thassos, the immersive installation features nine marble sculptures made by the designers using off-cuts, as well as some seating installations.

Petaloti jokes that Italy has always been good at selling itself, from furniture to olive oil, whereas Greece has been “very introverted”. Which is why Objects of Common Interest jumped at the chance to be involved in a collaboration with the Greek Marble Association. Greece has been realising that its stone trade, which can trace its history back to the Parthenon, has something to say. In fact, at the end of 2022 the association, with the backing of Enterprise Greece investment entity, created a brand name to help bring it to the world: “Greek Marble: Then. Now. Forever”.

The Alcova installation is an important step. “We haven’t worked on our branding and storytelling [until now],” says Irini Papagiannouli, the third-generation family member of John Papagiannoulis Bros, one of the companies that has supplied stone this year. “But the history is there.” Irini has been instrumental in helping to turn the Design Week show into a reality.

Objects of Common Interest’s Petaloti admits that she didn’t always like marble growing up. “It was everywhere,” she says. “A plaza, a church, people’s houses if they wanted to be fancy in the 1980s and 1990s.” But she has come to fall in love with the fact that it is part of Greece’s “cultural DNA”, witnessing it first-hand working with a seventh-generation marble maker from Tinos. In fact, Objects of Common Interest’s first design, the Bent Stool from 2016, was made from the material. Nonetheless, the concept behind “Soft Horizons” has been to get away from the imposing and sometimes overwhelming way in which marble is often presented and instead go for something “ethereal”, as Petaloti puts it.

The “Soft Horizons” objects, which the studio calls totems due to the way they are assembled, each use several different pieces of marble that have names as diverse as Thassos Silver stream and Arabescato Kasta, and sit on top of a water pond, while two of the pieces will react to motion and move as a visitor approaches (“It’s a comment on how marble and humans have the same link to nature,” says Petaloti). A red, disc-like speaker from New York’s Oda hangs above the installation, playing sounds from the production process. While all the focus has been on the Alcova show, Objects of Common Interest say that this is the starting point for taking Greek marble around the world. “This isn’t about impressing because it doesn’t have that scale,” adds the designer. “Instead, it’s a personal dialogue with a material.”

objectsofcommoninterest.com

For our seasonal rundown of the best in spring style, we present the top designers, creatives, products and brands on our radar – from the irreverent bursts of colour on a new Prada trainer to Saint Laurent’s fresh take on double-breasted blazers. Plus: the luxury watches making us tick.

1/25

Tod’s

Italy

Tod’s has been an authority in leather goods for decades but ready-to-wear has made up a smaller part of its business. Things are changing under Matteo Tamburini, its recently appointed creative director. For spring he is combining lightweight tailoring with breezy cotton shirts, draped dresses and pleated leather pieces. His sunny colour palette has also been a crowd-pleaser. Expect Tamburini’s star to rise even higher in his new role.

tods.com

2/25

Informale

Australia

Melburnian menswear label Informale is bringing Neapolitan flair to its home city. After working for luxury labels such as Zegna and Gucci, Steve Calder, the brand’s co-founder and creative director, decided to introduce a more relaxed suiting approach to Australia, chiming with the country’s sunny lifestyle. “Men here want to dress up but aren’t necessarily comfortable in a suit,” says Calder. “So we started to make linen trousers that can be worn with tailored blazers. And from there, we grew through word of mouth.”

Informale’s core collection includes shirts, utility vests, knitwear and high-waisted tailored trousers that capture the smart-yet-breezy look that Australians do best.

The brand’s main atelier is in Melbourne; it also works with specialists in the city, as well as shirt-makers in Naples. “We move at a slower pace but it works in our favour,” adds Calder. “I like a brand that has a romantic story behind it.”

informale.com.au

3/25

Marie Marot

France

After several years working in the film and communications industries, Paris-based Marie Marot decided to launch a business based around shirts. Her label offers appealingly oversized pieces in versatile shades of blue, white and pink, as well as classic check patterns and bright-yellow stripes for the sunnier months.

Marot is her own best customer. You might spot her cycling around the French capital in one of her classic blue garments, often worn under a gilet.

Over a coffee on Place des Vosges, she tells Monocle that she is committed to perfecting her signature designs, which she sells through her online shop at competitive prices.

Sometimes Marot updates her collections with new hues or adds details such as ruffled collars. Mostly, however, she ignores seasonal trends and shuns fashion’s endless search for novelty. “A lot of people bring on investors, expand their collections too quickly and work with hundreds of retailers,” she says. “I want to take it slow and enjoy my life. It’s a much more honest approach.”

mariemarot.com

4/25

Prada

Italy

For their spring/summer 2025 menswear range, Miuccia Prada and her co-creative director, Raf Simons, have added bright pops of colour to their usual dark-grey and chocolate-brown tailored trousers, slim cardigans and leather coats. What they’re seeking to capture is a sense of “optimism”, “freedom” and “fantasy”: monochrome looks are broken up by nylon and suede trainers in hues including sunny yellow and forest green. “It’s the opposite of grandness,” says Prada. “There’s too much of that around.”

prada.com

5/25

A Presse

Japan

Kazuma Shigematsu has been collecting mid-century furniture for decades: wooden chairs, decorative objects and cabinets from Scandinavia and Japan, as well as France, Brazil and the US. “I like to mix cultures and tastes but there’s always the same feeling,” he says from his Paris showroom, where a postmodern chair with leather cushions sits in the corner. Vintage furniture from the 1950s and 1960s also captures the spirit of Shigematsu’s fashion collections for A Presse, the label that he founded in Tokyo in 2021. “I spent years consulting for larger companies and I was tired,” he says, referring to the ever-increasing pace of the fashion industry.

A Presse’s model is the antithesis of mass manufacturing, with limited-edition items designed to improve with age. Shigematsu believes that fashion shoppers should think of themselves as collectors. When it comes to quality, there’s little distinction between a handcrafted wooden chair and one of his leather jackets or workwear-inspired trousers. Silhouettes are executed to perfection, the stitching is done by hand and even the garments’ hangers are hand-carved. “The market has become too much about marketing and logos,” says the designer. “My concept is about understatement and not dressing for others. These clothes are for you.”

While Japan is known for its commitment to craft, this level of artistry is still unusual. “There are many Japanese brands but most are in the middle range,” says Shigematsu. “That can be a good thing but there’s too much focus on price points, cost-saving and marketing.” In such a context, the vintage flair and limited nature of A Presse designs are a breath of fresh air. The label has attracted an international clientele of connoisseurs (the US is one of the brand’s strongest markets) and larger retailers are knocking on its door. But distribution remains limited. A Presse has a few global partners, including e-commerce site Mr Porter, but the best way to access its wares is to visit its Shibuya flagship, where concrete interiors meet thoughtfully selected furniture and meticulously crafted wardrobe classics.

6/25

Salomon

France

Think of Salomon and what comes to mind is technical outdoor gear. Recently, however, the Annecy-based sportswear brand, founded in 1947, has been gaining traction in fashion too. Thanks to collaborations with luxury labels such as MM6 Maison Margiela and New York’s Sandy Liang, Salomon’s trainers have become coveted accessories. The brand’s latest launch, the XT-Whisper, made its debut during Milan Fashion Week. An updated version of the XT Hawk trail style, it has been redesigned with slimmer soles for more urban environments.

salomon.com

7/25

La Collection

Belgium

“Minimalism is the very essence of well-made clothes,” Florence Cools, a co-founder of Antwerp-based brand La Collection, tells monocle. “Every stitch is visible when the overall look is clean so everything needs to be perfect.”

To ensure that each item meets La Collection’s exacting standards, the brand prioritises natural fabrics, from fine Italian wool to raw silk spun on some of Japan’s oldest looms. These are fashioned into sculptural yet effortless-looking silhouettes – think column dresses in crepe silk, recycled-wool longline coats and linen hourglass blazers.

To finish off the look, Cools has also been working on a new range of gold jewellery, made by hand in the Antwerp diamond district.

“We are doing things the old way but with a fresh design perspective,” says Cools, who often draws inspiration from the works of German-American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Italy’s Carlo Scarpa. “I can’t walk through a city without looking at the lines, the structures of buildings and colour palettes,” she adds.

A passion for art has also made its way into La Collection’s universe. When you visit the label’s Antwerp flagship, expect to see Cools’ signature black-and-white creations alongside works of art by emerging UK-Belgian painter Eleanor Herbosch, Barcelona-based Aythamy Armas and Japanese artist Kiichiro Ogawa.

lacollection.be

8/25

Marie Adam-Leenaerdt

Belgium

After graduating from Brussels’ La Cambre art school in 2020, Marie Adam-Leenaerdt quickly found work at luxury houses such as Balenciaga. Three years later she debuted her namesake label and found almost immediate success, thanks in part to her experimental silhouettes, sharp tailoring and ability to put on a good show. Department stores including Bergdorf Goodman in New York and Stijl in Brussels bought her pieces; in 2024, LVMH nominated her for its annual design prize.

Last year she presented her collection in Parisian brasserie Terminus Nord, serving her guests oeufs mayonnaise while models walked down a makeshift runway. A recent show in March was held at the Galerie Paradis, where she lined up design and standard office chairs for people to sit on. “It raised interesting questions about the transience of fashion versus design,” says Adam-Leenaerdt. She hopes that her work will become collectable and transcend time. “I don’t want to reinvent things every six months,” says the designer. “I’d rather perfect a solid base. And I like dual structures: it’s about questioning how you can create two items in one. Having a Belgian heritage means prioritising ideas before aesthetics.”

marieadamleenaerdt.com

9/25

Connor McKnight

USA

Since launching his eponymous brand in 2020, Connor McKnight has made a name for himself with his sharp suits and ability to combine references ranging from vintage sportswear to 1930s suits. He is intrigued by utilitarian aesthetics, technical details and experimental fabrics, including vintage sleeping bags and South Korean military canvas tents.

“A lot of my work stems from everyday life and what I call ‘the times in between’,” he says. “There’s a lack of clothes that you want to put on, that will get you through your day and stand the test of time. Being able to have comfort and functionality is almost a luxury.” This combination is evident in the brand’s cashmere-and-merino sweaters and its double-breasted jackets, which walk the line between classic and modern. “A lot of things have been made before so my approach has been to refine and elevate.”

connor-mcknight.com

10/25

Nikos Koulis

Greece

Jewellery designer Nikos Koulis has opened a new Athens flagship. “After a decade in the Kolonaki district, which has a bustling mix of shops, cafés and restaurants, relocating to Voukourestiou Street was both a strategic choice and an organic evolution,” says Koulis. The new space, designed with London studio Bureau de Change, reflects Koulis’s ambitions to work with design and jewellery connoisseurs; labels from Hermès to Prada and Cartier have long been based in the area.

Koulis has built an international reputation for his unusual stones and art deco designs. The new flagship reflects his flair for contrast and artful interiors. “My jewellery caters to individuals who don’t feel the need to conform,” he says. “They know exactly what they want.”

nikoskoulis.com

11/25

Ven Space

USA

When Chris Green opened his multi-brand menswear boutique, Ven Space, in Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens last year, he knew exactly what kind of business he wanted to run: an intimate neighbourhood shop with a steadfast loyalty to the bricks-and-mortar experience. Ven Space, which stocks a thoughtfully selected range of luxury clothing, shoes and accessories, doesn’t offer online shopping; if you want access to its meticulous curation, you have to come in. Green is on the floor every day. “Retail has drifted away from the idea of the shopkeeper,” he says. Ven Space (ven means “friend” in Danish) is open to the public from Wednesday to Sunday, while Mondays and Tuesdays are dedicated to private appointments.

On the shop floor, you’ll find a mix of brands, such as Japan-based Auralee or Dutch label Camiel Fortgens. T-shirts from Our Legacy sit beside Dries van Noten button-downs and even the shapely ceramics dotted around the boutique are for sale. Green, who is a longtime resident of Carroll Gardens, hand-picks every item, guided by his personal taste rather than seasonal trends. “I don’t want to be everything for everybody,” he says. “If you try, you lose the strength of your idea and your point of view. So I started by thinking about what I would actually want to wear.” His commitment has paid off. Despite opening just six months ago, Ven Space has already gained a devoted following, with regular customers popping in to snag new launches. “We pride ourselves on getting to know the people coming through the door,” says Green.

ven.space

12/25

Q&A: Tolu Coker

UK

Coker is a British-Nigerian fashion designer who founded her brand in 2021. She draws inspiration from her Yoruba heritage while injecting a modern sensibility into tailoring. She is also among the semi-finalists for this year’s prestigious LVMH Prize. Here, she talks about the importance of putting emotion back into design and the art of tailoring.

What is your design process?

I lead with feeling. My research always starts with conversations and imagery but when I start creating, it becomes more instinctive. It’s similar to being in a state of meditation. I also consider the notion of value: the way we value clothes goes beyond the item itself. In fashion, this is usually equated to a high price point to create aspiration but there are also other factors to consider, such as our emotional connections to clothing. These are my starting points.

How do you approach tailoring?

Continuous fittings play a big part. I’m always thinking about form and how the body feels when it’s enclosed in something. When you’re designing it can be so conceptual that you forget that it’s about dressing people. Your process isn’t more important than the process of someone stepping into the garment.

What are your tricks of the trade?

There are zips or exaggerated sleeves that I often turn to. I’m always adding pockets to dresses. I love comfort and functionality.

tolucoker.uk

13/25

Bambou Roger-Kwong

France

“It’s all about the shape of a garment,” says Bambou Roger-Kwong, a former stylist who founded her eponymous label in 2022 in Paris. Her attention to detail, background in styling and mixed heritage (she was born in Paris to a Chinese mother and French father) inform her collections, which feature seemingly simple designs that can easily be transformed with a knot or a strategically placed button.

“When you look at a piece on the hanger it can seem basic but it’s all about the styling,” says Roger-Kwong, pointing to her signature pieces such as apron dresses and button-embellished wrap skirts.

They are all produced in a family-run factory in Portugal, using deadstock fabrics sourced from LVMH-owned facilities. Ceramic accessories, handcrafted at the designer’s Paris studio, add the perfect finishing touches.

bambourogerkwong.com

14/25

Gajiroc

South Korea

In the world of luxury menswear, influence is quickly shifting from large-scale runways and globally recognisable names to under-the-radar specialists, technicians and craft obsessives. At Paris Fashion Week men’s, the most exciting moments took place away from the catwalks and celebrity front rows and inside intimate, often hard-to-find showrooms. South Korean designer Gi Tae Hong’s set-up in the 10th arrondissement, was one such space.

In a compact, serene apartment, Hong invited editors and buyers to discover his chocolate-brown alpaca coats, left undyed to be extra soft; mud-dyed sweatshirts, handcrafted on Japan’s Amami island; and cashmere knits from Italy. “I aim for the best quality and best fabrics,” says the designer, who previously worked with San Francisco-based Evan Kinori.

When he moved back home, he wanted to create an antidote to the mass-produced, commercial lines that had taken over South Korea. He dedicated his early training to craft, learning everything from shoemaking to pattern cutting and shirtmaking. “When I can’t find someone to craft my designs, I just do it myself,” he says.

gajiroc.com

15/25

Convenience Wear

Japan

Convenience stores, known as konbini, are an indispensable part of life in Japan, though they have mostly shunned fashion. This changed when Family Mart, the country’s second-largest chain in the sector, teamed up with designer Hiromichi Ochiai to launch Convenience Wear. The clothing line started small but rarely has a brand taken off so fast: its unisex crew socks flew off the shelves, with 1.4 million pairs being sold in a year. “In Japan, the konbini represents a feeling of stability and safety so I wanted to express this very clean image,” says Ochiai, who worked with graphic designer Takahiro Yasuda and his team Cekai on the line’s sleek branding. “In many ways, the konbini is a difficult environment for selling clothes,” he says. “There’s so much going on and the 24-hour lighting is tough.” That’s why his designs focus on simplicity and functionality. You can now buy everything from Convenience Wear T-shirts to sandals and handkerchiefs.

Ochiai, who has his own label, Facetasm, is already thinking of new categories, such as trainers. “We want products to be simple enough for people of all ages, occupations and nationalities to understand immediately,” he says. With Nigo, Kenzo’s celebrated artistic director, now also on board as the wider company’s creative director, expect to see more product collaborations, refreshed shop interiors and bold marketing campaigns from Family Mart.

family.co.jp

16/25

Lafaurie

France

Lafaurie is a study in Parisian style. “It’s the art of standing out without going over the top,” says Théo Lafaurie, who co-owns the menswear label with his brother, Pablo. The brothers inherited the label from their father and have continued to build on its commitment to high-quality manufacturing by working with the family’s network of artisans and manufacturers in Europe. They have finessed relaxed blazers and trousers that provide an elegant alternative to formal tailoring. “We like to play with dress codes and provide suits that aren’t too tailored or formal,” says Théo.

lafaurieparis.com

17/25

Saint Laurent

France

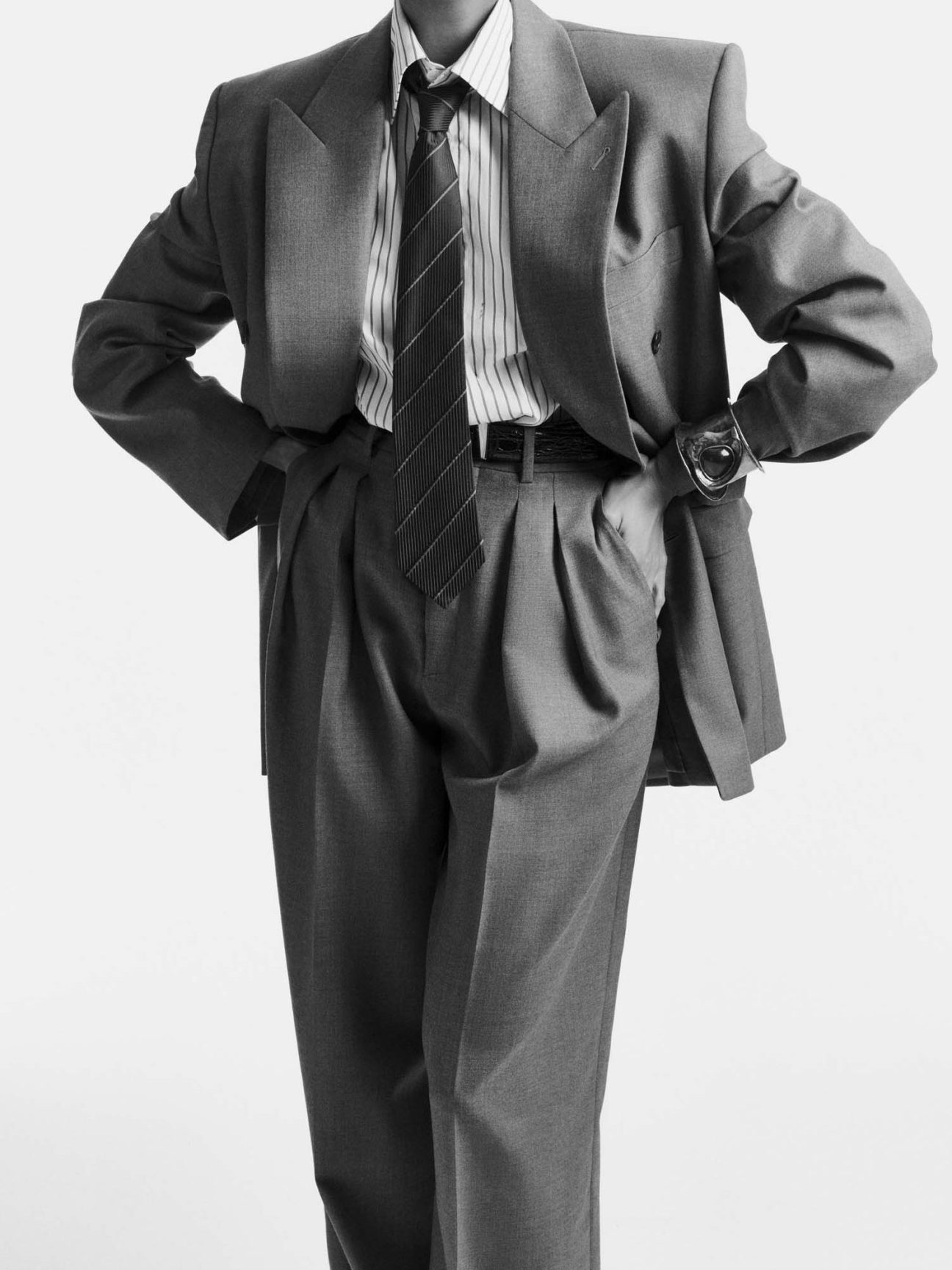

Even amid the slowdown in the luxury market, the desirability of Saint Laurent’s clothing hasn’t waned, mostly thanks to the way that the brand’s creative director, Anthony Vaccarello, constantly reinvents its codes. For spring he recreated the tailored uniform of founder Yves Saint Laurent: double-breasted blazers with broad shoulders and pleated trousers, paired with patterned ties and black-framed glasses. It’s a simple yet effective formula that makes a compelling case for a sharp jacket.

ysl.com

18/25

Watches

Global

Bold or understated? There’s something for everyone in this timely spring selection of watches. Cartier’s Baignoire, with its sleek oval face, is a modern-day classic, while Longines’ Mini Dolcevita features an alligator strap that will bring a touch of restrained elegance to your wrist.

If you want diamonds, look to Chanel’s J12 Diamond Bezel watch, which marries highly resistant ceramic with precious stones. This dazzling combination can also be seen in Hublot’s aptly named Big Bang watch, which contrasts a steel base with diamond details.

cartier.com; longines.com; chanel.com; hublot.com

19/25

Neighbour

Canada

When Saager Dilawri founded multi-brand boutique Neighbour in Vancouver’s Gastown district in 2011, he sought to create a sartorial hub for people who were interested in craftsmanship without the pretension. “New York shops felt a little too cool for school,” he tells Monocle. “I wanted an approachable space, where someone could come in to talk to me about clothes and I could learn from them too.” At the time, there were only a handful of menswear boutiques in the area, focusing on streetwear or premium luxury. “I have always been more interested in Scandinavian design so I felt that I could offer [customers] a different option,” he adds. Since then, he has introduced numerous brands to Canada, including Swedish stalwart Our Legacy.

His love for high-quality fabrics also led him to Japan, where he forged partnerships with labels such as Auralee and Comoli. For a business that operates locally, it has a decidedly global perspective – a reflection of Vancouver’s diverse make-up.

His online shop, often featuring atmospheric imagery from Tokyo’s yokocho alleys, has become a point of reference for menswear veterans across the globe. “When we started, most brands didn’t have an online shop, which gave us an opportunity,” he says. This combination of storytelling and craft is what keeps customers returning to Neighbour. “People want something different,” he says. “They want to know about the story behind the brand. That’s not going to go away.”

shopneighbour.com

20/25

Gucci

Italy

Italian label Gucci might be going through a period of transition following the exit of creative director Sabato de Sarno in February but its heritage continues to win over luxury audiences. This spring the brand is returning the spotlight to its Bamboo bag, a house classic that dates back to 1947. It is being reissued in a variety of new shades, from classic black and ancora red to a seasonally appropriate green.

Silk scarves have also played a pivotal role in Gucci’s history. In the 1960s, Rodolfo Gucci commissioned the Flora silk scarf as a gift for actress Grace Kelly.

The house’s new scarf collection, The Art of Silk, features illustrations by nine artists. Take a leaf out of Kelly’s book and tie one of the scarves loosely around your neck, pairing it with a white shirt.

gucci.com

21/25

That’s So Armani

Italy

Italian fashion house Armani is enjoying something of a renaissance. The brand has recently celebrated the opening of its New York flagship, the renovation of its Via Manzoni outpost in Milan and a collaboration with US label Kith. Now a new line called That’s So Armani has made its debut. Featuring sleek, mostly monochromatic tailoring cut from high-quality materials such as vicuña wool and cashmere, the collection includes double-breasted blazers, trench coats and knitwear that will bring a touch of Milanese elegance to any wardrobe.

armani.com

22/25

Chloé

France

German designer Chemena Kamali has breathed new life into Chloé, reinvigorating the brand with the free spirit and relaxed elegance that its founder, Gaby Aghion, was known for. The brand’s spring/summer collection consists of a range of easygoing crochet sets, maxi dresses and lightweight trench coats, which are paired with shell-shaped jewels and charming pillbox hats. These are looks to relax in while embracing carefree spring days.

chloe.com

23/25

KLH

Germany

When shoemaker Korbinian Ludwig Hess opened a workshop on Berlin’s leafy Hohenzollernplatz in 2017, he started hanging the shoe lasts that he made for his clients on the wall. Some eight years later more than 200 sets line three sides of the atelier. They represent the well-heeled clientele that come to klh for bespoke dress shoes, Chelsea boots and ballerina flats, all of which are made using old-school techniques and require a six month wait. “It’s more about quality and aesthetics than about tradition,” says Hess, who honed his craft by working for Austrian shoemaker Rudolf Scheer & Söhne. “Machines just can’t do things as well as we do.” Hess can make a welted Viennese dress shoe as well as anyone but has also carved out a niche with boots and loafers that have slightly pitched, Western-style heels. He wants to recreate the feeling that he had when he bought his first pair of cowboy boots at the age of 16. “I remember putting them on and suddenly walking differently,” he says. “[The right shoes] can change who you are.”

klh-massschuhe.com

24/25

Cristaseya

France

Cristina Casini always asks herself what she would want to buy if she were a customer at Cristaseya, the Paris-based ready-to-wear label that she founded in 2013. “When I started I looked at everything that I owned for the cut or fabric,” she says. “Then I set out to make pieces that you could wear all of the time – clothes that would make you feel powerful because they were both elegant and comfortable.” More than a decade later, this remains an accurate way of describing the brand’s largely unisex clothing, which consists of oversized shirts, tapered trousers and tailored jackets.

To highlight the timelessness of the label’s designs, Casini works on only two editions per year, which feature a mix of new releases and reissues of existing designs. “Brands have to change so fast these days,” she says.

“Our customers feel tired of the overconsumption of fashion today. We prefer to focus on quality.”

The best way to shop for limited-edition Cristaseya designs is by appointment at the brand’s showroom-cum-boutique in Paris’s 9th arrondissement. It’s here, at the label’s industrial chic home, that Casini’s flair for intimate shopping and craftmanship becomes most evident. Signature fabrics, from Japanese washi-wool blends and denim from Marche to knits from Casini’s mother’s atelier in Reggio Emilia, can only be fully appreciated when seen in person.

cristaseya.co

25/25

Bottega Veneta

Italy

Bottega Veneta’s second collection of fine jewellery builds on last year’s debut. We have our eye on the label’s Alchemy set. The necklace holds 380 diamonds, as well as 19 black onyx and 19 green agate stones. It is handcrafted over a period of 15 days by the house’s expert artisans in Vicenza.

bottegaveneta.com

The speed with which the Trump administration has withdrawn US security commitments to Europe, at least verbally, has been a wake-up call. But even before Trump’s re-election, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine had prompted European nations to boost defence spending, acquire advanced weaponry and enhance industrial production. Yet one pressing challenge remains now as then: a lack of numbers. Ukraine’s struggles to maintain troop levels in a prolonged conflict have highlighted Europe’s recruitment issues. Nato planners currently assume that, in the event of a Russian attack on a European member and the subsequent activation of Article 5, the 100,000 US soldiers stationed on the continent would be swiftly reinforced by up to 200,000 more. Without this commitment, Europe might require an extra 300,000 troops under unified command as well as a short-term annual defence spending increase of at least €250bn to deter Russian aggression. But how will they get those troops?

Many European countries abandoned mandatory military service following the end of the Cold War. In recent years, debates around a return to conscription have reignited across the Old Continent. Since the start of Trump 2.0, these have increased in fervour. Supporters argue it could help to build military reserves, strengthen civil-military relations and enhance resilience in times of crisis. Northern and Eastern European countries are often cited as models, as many Baltic and Nordic nations retained some form of mandatory service after the USSR collapsed or reintroduced it in response to the growing Russian threat. But despite its potential benefits, conscription is far from a universal solution. Each country must navigate distinct political, demographic and strategic circumstances.

For democracies, public sentiment remains a hurdle. In 2024 a Gallup poll revealed that only 32 per cent of EU citizens would be willing to fight for their country in the event of war. Opposition was strongest among younger age groups: 59 per cent of Germans aged 18 to 29 rejected the idea in a poll commissioned by the magazine Stern. According to a YouGov survey from 2024, resistance is particularly high in the UK, with a third of respondents aged 18 to 40 stating that they would refuse military service even in the event of invasion. Much of this reflects the problem of “strategic cacophony”. Public attitudes towards conscription are strongly influenced by perceptions of security: the more severe the threat, the greater the public support. In Latvia and Estonia, for instance, initial resistance to conscription shifted significantly after February 2022. The former has now reintroduced it while the latter has widened compulsory military service.

On the other hand, some Nato military officials have voiced apprehension about the effectiveness of large-scale conscription programmes. These concerns stem primarily from the challenge of properly integrating conscripts into professional military outfits, which have had access to superior training and equipment. While these issues have not deterred a few European countries, such as Croatia and Serbia, from pushing ahead with programmes reinstating some form of mandatory service, others such as Germany have proposed alternative policies designed to address the manpower issue. Some are straightforward, such as making professional military service more attractive through financial and other incentives. Others are more innovative, including efforts to expand voluntary service and integrate reservists into roles beyond conventional operations, such as critical infrastructure protection and maintenance, or cybersecurity. Many of these non-mandatory options can also be seen as compromises. Politicians of different stripes are reluctant to push their populations into “prewar mode”, fearing how they might react.

Ultimately, whichever path a given European country chooses to pursue, it must do so with the understanding that the US security guarantee can no longer be taken for granted. Conscription is merely one of the means to an end; what is clear is that ensuring long-term security will require a much broader societal shift. As Ukraine has demonstrated – and many Europeans are yet to realise – national defence is not solely the responsibility of professional armies. In times of existential threat, citizens will be required to protect and sustain the war effort.

Grgic is Monocle’s security correspondent.

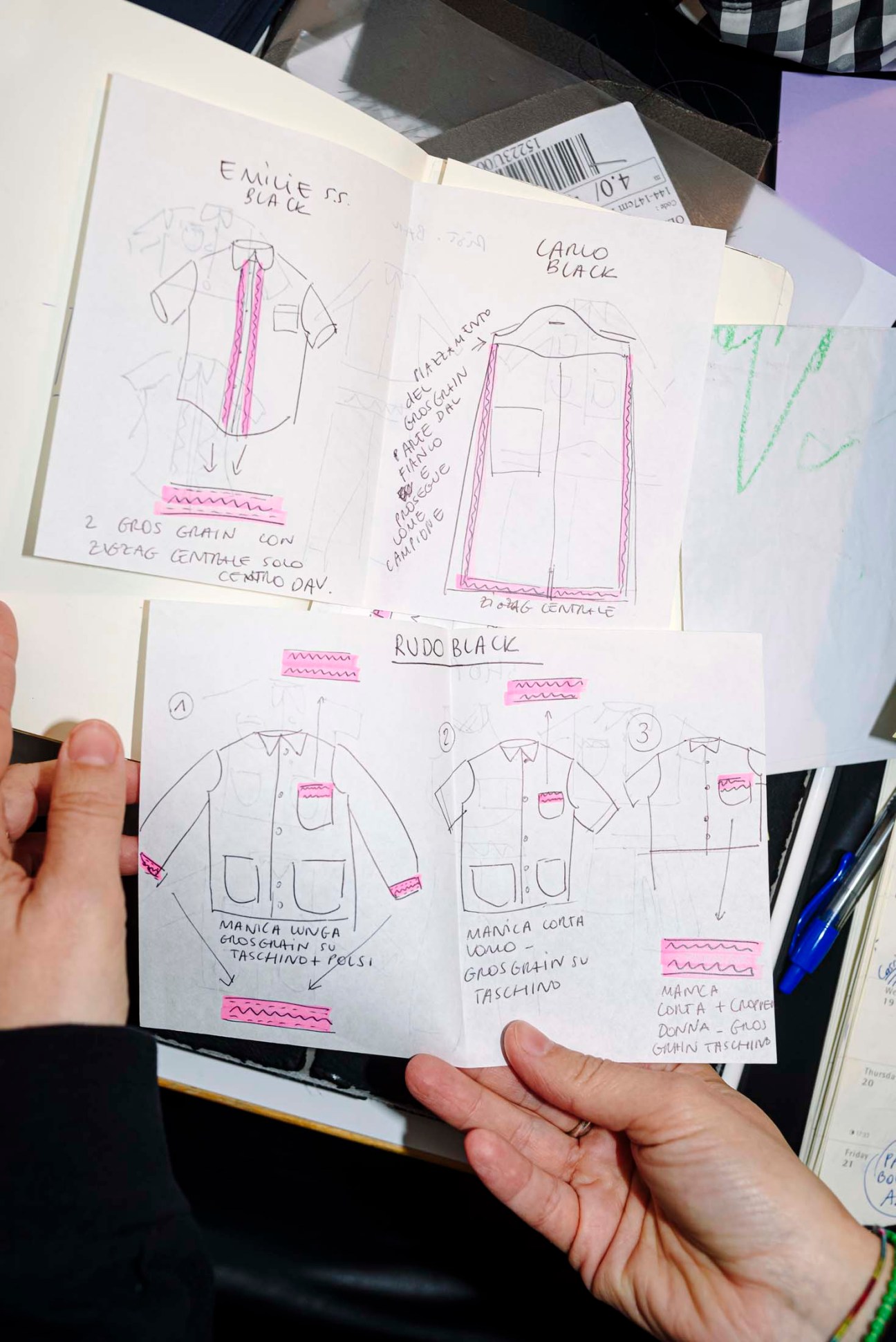

Morten Thuesen has a specific soundtrack for uniform fittings. Up on the fifth floor of a period apartment building just off Milan’s Corso Indipendenza, 1990s Japanese ambient music is spinning on a record player stationed on top of a striped Carolino drinks trolley made by the studio. In one corner of the showroom and living space, near a reupholstered Anfibio sofa from Alessandro Becchi, models are trying on the studio’s latest bespoke collection: “Made in Italy” uniforms for positions from front desk to outdoor agent, made specially for the spring reopening of Belvedere Hotel on Lake Como.

Hospitality uniform supplier Older’s unwritten mission statement is to get away from stuffy looks pedalled by bigger, more traditional firms. Founded in Paris in 2013 and relocated to Milan since 2019, fashion school graduates Thuesen, originally from Denmark, and his Tuscan partner Letizia Caramia head the operation. The pair met working for Alexander McQueen in London before moving to France.

Business has been what Thuesen modestly calls a “slow, steady burn”. In the past 12 years, Older has built up a staff of nine and more than 400 clients, including 10 Corso Como in Milan, Sushi Park by Saint Laurent in Paris, The Hoxton Hotel Group in London and DDD Hotel in Japan. “We’ve never had a PR or spent on marketing,” says Thuesen, explaining that the brand has grown by word of mouth. “It has been incredible.”

Older’s approach immediately appealed to Giulia Manoni, Belvedere’s co-owner, who attended the final fitting for the collection with her friend, the hotel’s management assistant Alice Bellomo. Coming in blacks, greens and blues depending on the job, the uniforms are striking, with pleated details that reference the hotel’s architecture. That’s not to say that Older puts style over substance: the pleats have been sewn in such a way that they don’t need ironing and the outdoor jacket’s hood and sleeves can be removed to suit the season. “The other companies are very regular and the fabrics not very nice,” says Manoni. “Plus, I make choices based on the people behind the project.”

Manoni isn’t the only person to have been won over by Older’s founders. If attending a fitting feels like you’ve been welcomed inside their home, that’s because you have: the couple live in an adjoining part of the apartment with their young son. Matteo Pancetti, co-owner of Porta Romana’s Yapa restaurant, whose staff wear Older uniforms, remembers visiting and bonding with Caramia over shared Tuscan roots. “It’s very urban, it’s minimal,” he says of the Older look. “I’ve always compared it to a Carhartt for the kitchen.”

Still, things could have been different. Older started as a ready-to-wear fashion brand in Paris but the couple grew increasingly disillusioned with the scene. At a New Year’s Eve dinner in Copenhagen, surrounded by chefs and architects, they hit on the idea of uniforms, noticing a gap in the market for good-looking garments at the sorts of places they liked to visit. “It came out of need,” says Caramia. “And we needed a good idea.”

Older now has 75 EU-made pieces in the permanent collection, not to mention bespoke options. But the founders had to learn a lot on the way. With their first client, Restaurant 108 in Denmark, they soon realised that cotton uniforms didn’t stand up to chefs’ scrutiny. Since then, Older has developed a stain-resistant fabric that is easy to care for. The permanent collection uses a gabardine sourced near Rome, which mixes organic cotton with recycled polyester in three weights and six colourways.

You will see these uniforms in establishments all across Milan, from the bespoke all-black look of retailer 10 Corso Como to the beige aprons used at ceramics producer Officine Saffi Lab and the long-sleeved navy Rudo jackets, complete with woven logo labels, worn by staff at gourmet food shop Terroir. But Older’s uniforms aren’t always about the most visible member of a hospitality team. Thuesen says that the studio’s utility belt, the Frits, is the studio’s “love child”. And equal attention goes into the outfits for room cleaners and dishwashers. “Those are two of the most important positions,” adds Thuesen. “I like the idea of them becoming iconic.”

As Older continues to move in new directions, including a recent b2c uniform capsule collection with Japan’s Facetasm, it remains committed to growing organically, with no outside funding and with the couple very much at the centre. “Letizia is very creative and Morten contributes the intellectual and research part,” says Valentina Ciuffi, curator and co-founder of Milan Design Week’s Alcova platform. Ciuffi commissioned Older to make uniforms for her staff and even featured a large Older-made cabinet in last year’s show – a reminder of the studio’s design versatility. Today its furniture is represented by Milan’s Nilufar gallery, while the pair recently wrapped up a silk-screen exhibition at Milan’s Dropcity.

Despite the need to try new things, though, Older’s founders still come back to uniforms. “If we get bored, we do something else,” says Caramia. “But we always happily return. Ultimately, what we love most are clothes.”

olderstudio.com

Older around town

With buyers from Switzerland to South Korea, Older also has a diverse clientele on its doorstep in Milan.

1.

10 Corso Como

The concept store changed ownership last year. The new leadership decided that its staff needed a new visual identity – cue Older’s bespoke, all-black uniforms for the café, shop and gallery space.

10CorsoComo.com

2.

Yapa

Yapa uses Older’s Olafur aprons for staff in its open-plan, customer-facing kitchen. Three front-of-house staff wear Older’s Matteo trousers. “They’re not heavy,” says owner Matteo Pancetti. “They’re beautiful.”

ya-pa.com

3.

Terroir

Gabriele Ornati, owner of the food shop that opened in 2017, gladly stocks Older’s clothes, plus a bag he designed with them collaboratively. Staff wear the Hans aprons and Rudo jackets, the latter with a bespoke woven logo label.

terroirmilano.it

4.

Officine Saffi Lab

This “lab” near the Isola neighbourhood is the commercial arm of the ceramics design foundation of the same name, its clients include Bottega Veneta. Director François Mellé calls his staff’s Older aprons “stylish but also functional”.

officinesaffilab.com

5.

Sandì

In this small, family-run restaurant with a twist (see Issue 181), kitchen staff wear Older’s white Cuban shirt and Harry trousers; front of house wears the Rudo jacket in navy and Giulia trousers in grey.

Via Francesco Hayez 13

Deep inside the sprawling Lackland Air Force base in San Antonio, Texas, is the headquarters of the Transportation Security Agency’s (TSA) Canine Training Center (CTC), where Monocle rolls up on a foggy day to see a man about a dog. Or, perhaps we should say, several dogs. If you have seen a working canine in a US airport, there is a good chance that it, as well as its handler, has spent as long as four months here, undergoing an intense training regimen. The 300-plus dogs that are trained here every year are split into two groups: those that search planes, vehicles and other stationary objects, and those that search people. Unlike the detector dogs employed by agencies such as US Customs and Border Protection, which can search out drugs and money, or “biosecurity” dogs in countries such as Australia, trained to look for undeclared agricultural items and invasive species, CTC dogs are looking for just one thing: explosives.

“We are the world’s largest canine explosive-detection programme,” says Zebulon Polasek, the director of the CTC, while standing in the facility’s lobby on a rug emblazoned with the US flag and a pack of dogs. TSA spokesperson Patricia Mancha adds that, for obvious reasons, the agency does not divulge which specific explosives its canines are trained to detect. But it can be assumed that these include widely used plastic explosives, such as C-4 and the chemical compound PETN, a favourite of Al-Qaeda, that featured in an abortive 2010 plot in which printer-toner cartridges bearing explosives were placed on board a ups cargo plane and two Qatar Airways flights. Nor does the agency publicise the details of any successful operations.

In one of the few glimpses behind the two-way mirror, TSA did report in 2023 that a canine team at Southwest Florida Airport flagged a potentially suspicious employee who, it turned out, had been at a shooting range and was bearing trace elements of gunpowder. But this is hardly at the higher end of the security-threat level that the agency deals with on a daily basis. The TSA was created as a response to the September 11 attacks as a way of centralising, and thereby improving, security at US airports. But as the threat has evolved, so too has the canine training. The 2001 “shoe bomber” and the 2009 “underwear bomber” episodes, for example, necessitated an expansion of focus. “The dogs were used to inanimate, stationary targets such as carry-on bags that didn’t move or breathe,” says James Kohlrenken, the CTC supervisory training instructor. “We came up with how to teach dogs that people are productive ‘items’ to search.”