When the Napraforgo Street enclave was built in the space of a few months in 1931, it was revolutionary. Similar in spirit to the so-called Werkbund estates in Austria, Germany, Poland, Switzerland and Czechia, the idea behind the low-rise suburb was to create a new model for urban living. Building detached, single-family homes was hardly the norm at a time when Budapest, like the other great cities of Central Europe, was reeling from a profound housing shortage.

Sitting on the quieter Buda side of the Hungarian capital, the neighbourhood is well served by tram and metro lines, meaning that the city’s fairytale-like parliament building is a mere 30 minutes’ walk away. And yet, Napraforgo still feels like a world unto itself.

The 22 houses of Napraforgo – Hungarian for sunflower, a name chosen to highlight the houses’ airy design – vary in size but range from 140 to 250 sq m. They strech over two or three storeys and sit in a small plot of land, each flanked by a garden. Unlike its Werkbund counterparts, there is little rigid stylistic uniformity, though all the units adhere to the principles of modernism and, more narrowly, the Bauhaus school. Indeed, many of the architects involved – 18 firms – studied in Germany, including one at the Weimar school itself. Others, such as Alfred Hajos, had backgrounds as inventive as their creations. Before forging a career in architecture, Hajos was Hungary’s first Olympic swimming champion, a runner and footballer. In Napraforgo, he designed House No 19, now home to Dora Groo and her husband, Gabor Megyeri.

Groo, a medical researcher before she retired, is the only descendant of an original owner family still living here. Her grandparents’ motivation for moving to Napraforgo sounds as relevant today as it did then. “My grandfather was a mid-level banking manager, and his wife and their children, including my mother, were living in the centre of Budapest but wanted to move somewhere green,” says Groo as she settles into the downstairs living room with her husband, a chemical engineer whom she met and married in the 1970s. Behind her, a swirling wooden staircase leads up to the first floor, where there is a bedroom and an office, complete with original beds and bookcases, as well as a sunny terrace. Yet to Groo, it doesn’t feel like living in a time capsule. “I have lived in this house since I was born so for me it’s not a museum. We raised our two children here. This street was created as a place to live.” And life has been plentiful. By the late 1930s, some of the original owners – mainly from the middle-class intelligentsia with the occasional aristocrat and military officer – moved out as war loomed. After 1945, as Hungary became communist, some buildings were requisitioned and subdivided to house multiple families, before another wave of selling and reselling reshaped the street.

Throughout, the ensemble remained intact but some degree of protection was necessary and in 1999 (much too late for Groo’s liking) the street was finally given listed status. By then, however, many alterations had already been made to the original designs, a consequence of Hungary’s lax heritage rules and the upheaval – and rampant speculation – that followed the fall of the Iron Curtain.

In 2017, Groo and Megyeri founded the Napraforgo Street Bauhaus Association, both to help secure the ensemble’s historic status and to establish a shared archive of materials while raising public awareness. The results are encouraging: there are now guided tours, as well as a strong interest in purchasing. Despite limited availability, the houses still come up for sale with some regularity. One two-storey house – designed by architect Ervin Quittner, who later built several factories in Budapest and served as president of Hungary’s touring club – recently sold for a little more than €1.1m.

In keeping with the homes’ original ethos, their new owners tend to come from the creative industries – a phrase that wouldn’t have existed in the 1930s. No 1 stands at the head of the street and forms a symbolic gateway with views over a football pitch. Lawyer, journalist and art collector Erno Muranyi lives here with his wife, who is also in the legal profession, and their teenage daughter. They moved a year ago into a property that had belonged to the dean of law faculty of the university they attended. The Muranyis had been living on a nearby street and would often walk through Napraforgo, wondering what it might be like to have a house here all to themselves. “We saw our dean many times here and greeted him,” says Muranyi. Then, the dean’s nephew – a family friend – asked whether they might be interested in taking over. “My wife said, ‘Call him immediately!’”

Like most of the other houses, the Muranyi residence is furnished with antiques, though not necessarily all from the Bauhaus period. There are cupboards from the turn of the 20th century, heavy desks and bookcases from the 19th, and even furniture from the 18th century sofa. In this respect, the Napraforgo estate stood apart from similar projects elsewhere, where buildings typically came with furniture and fittings included as part of the package. But from the very start, Napraforgo owners had the freedom to choose their own decor so true modernist pieces, like those in the home of Groo and Megyeri, were comparatively rare.

Nevertheless, the 1930s interior design aesthetic remains strikingly modern – and many now aspire to it. Returning the original feel of her new house is the aim of another recent arrival, Andrea Mari. Mari runs a furniture showroom in Pest and owns three properties across Buda, including House No 11 (formerly 13) in Napraforgo. The house – an elegant corner building designed by architect Laszlo Vago, a member of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne group, which included Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and celebrated Soviet constructivist Moisei Ginzburg – had been altered by its previous owners, who added a controversial extension.

Budapest architecture firm Rapa is now planning a discreet overhaul (the extension – essentially a windowed winter garden – will remain), which will introduce thinly framed windows to allow even more light, while keeping amenities, such as the kitchen and bathrooms, up to modern standards. “We have to respect the past but also do something new with these buildings,” says Mari. Rapa co-founder Adam Reisz is still waiting on approval from heritage authorities.

“The biggest challenge is how to modify the exterior and interior in a way that reflects the original architect’s intentions but in a modern manner so we have had to find this connection between then and now,” says Reisz. But he is undaunted – not only because of his expertise in dealing with historic architecture but also because of the overarching spirit of the Bauhaus, which championed technical innovation.

For Mari and her daughter, Nora Szeleczky, a recruitment expert who lives in the house, there is something else about Napraforgo that makes it special – the sense of community that they say has all but disappeared in Hungarian cities. “People are very individualistic now,” says Szeleczky, who lived in eight countries, including a seven-year stint in Vancouver, before returning to Hungary. She believes that this has prepared her for life here. “This street was built around the idea of community. It is unique in Budapest and anyone moving in should expect to be open with their surroundings – and with their neighbours.”

In the know: Napraforgo

Cost per sqm:

Between 2m and 4m Hungarian forints, or €5,000 to €10,000.

Best school: Pasareti Szabo Lorinc School

Set on a hill above a stream, just across a bridge from Napraforgo Street, this bilingual Hungarian-English primary and secondary school counts Groo and her two sons among its alumni.

Amenities and cafés:

The Pasareti roundabout hosts all the essential amenities, including a pharmacy with a natural cosmetics section, a medical centre and the much-loved Pasaret Bisztro, a favourite of locals for daily meals. A few streets away is the Szepilona Bisztro, offering an international menu that blends Hungarian and Austrian classics, such as tafelspitz (boiled beef), with French and Italian dishes.

Further info:

Groo and Megyeri’s association can assist with any inquiries and can be contacted through napraforgoutca.hu

With its exposed ventilation ducts and industrial setting in southwestern Milan, Acqua di Parma’s HQ feels a little tech corp – surprising for a century-old perfume and lifestyle brand known for its sun-soaked yellow packaging and zesty fragrances. In fact, you’d half expect the Acqua di Parma mothership to occupy an opulent central-Italian castello.

While the company’s CEO, Giulio Bergamaschi, doesn’t want you to reconsider everything you think you know about Acqua di Parma, he has been leading a quiet revolution since joining the business in 2023. He might keep returning to words like “consistency” and “heritage”, but he is intent on introducing fresh perspectives on the brand’s signature products and inviting designers and artists to “play” with its perfume bottles and accessories.

While the 1990s saw a short-lived push into leather goods and bags (at the time, Acqua di Parma was part-owned by former Ferrari supremo Luca Cordero di Montezemolo and Tod’s chairman Diego della Valle), Bergamaschi is looking to turn back to craft. Under his watch, crockery, glassware and other home goods have been reintroduced, including a Murano glass collection in collaboration with French-Iranian architect India Mahdavi.

Founded by Baron Carlo Magnani in 1916 in the central Italian city from which it takes its name, Acqua di Parma started out distributing its flagship Colonia (cologne) through tailors’ shops. It has travelled some distance since then. Long based in Milan – and acquired by lvmh in 2001 – the brand is now eyeing new markets worldwide, opening standalone boutiques in cities such as Riyadh and New Delhi, and continuing to diversify its offer.

Bergamaschi, who took the reins after 19 years at L’Oréal and a short stint at LVMH stablemate Loro Piana, has been developing what he calls a “polysensorial” strategy, including a wide variety of products you can touch, see and smell. His vision extends Acqua di Parma beyond its signature perfume ranges and into every aspect of the art of living.

Speaking from his Milan office, filled with books and watercolour paintings by Acqua di Parma collaborator Luca Scacchetti, he tells Monocle how he plans to achieve his ambitious goals, all the while staying true to the house’s playful Italian spirit.

Acqua di Parma is a big brand but it sounds like you want to return to its roots.

Craftsmanship and the art of living have been at the heart of Acqua di Parma for a very long time. Since I arrived, we have looked to expand this dimension and find a space for it in our boutiques. It would be very difficult to give these pieces the right place in a wholesale shop or a department store.

Do you see these products as being sold solely in your standalone shops?

They’re going to be at very selected top stores, including our boutiques, of course, and places such as Harrods and Le Bon Marché. The role of our boutiques is to offer the pinnacle of the Acqua di Parma experience: the best immersion in the Acqua di Parma universe, the best advice, the widest offer, plus these masterpieces that are only available in very limited [quantities].

Why are limited-edition items worth the investment?

Today people are increasingly looking for creativity. This is something extremely important, not only in Europe and in the West but also in Asia. If you think about markets in the Far East, you might [assume] that there is standardisation. But these days, even if they have a huge scale, they’re looking for something special.

There is a concept in Italy that has always inspired me, called artigianato artistico (artistic craftsmanship). It’s an idea of craftsmanship in which the human dimension is very present, not only because there is the perfection or imperfection but also because the human injects creativity into the craftsmanship – and that’s why it becomes artistico. Is it art? Not exactly. Is it artiaganato? It’s more than that. Is it design? It’s not 100 per cent industrial. This is something that inspires me very much – and it is a north star that we are going to follow in the future.

What’s your retail strategy for Acqua di Parma?

Before looking at geographical expansion, we’re thinking about our current distribution and improving the shopping experience. We need to be more and more Italian but also [embrace] some local cultural codes. Of course, we are an Italian maison, so we need to be consistent and stand for Italian heritage and Italian values. But that does not mean that we need to standardise our image everywhere we go.

Fragrance is at the heart of what you do but it’s now a crowded marketplace. Has that made you change your approach?

It has only reinforced the importance of being consistent with heritage and working on an original value proposition. This is where I can bring a certain added value in making clear who we are, redefining our original angle and increasing the house’s creativity. Acqua di Parma has always stood for elegance, sophistication, craftsmanship and timelessness. But it is Italian – and, being Italian, it is also [synonymous] with a certain light-heartedness and playfulness.

This is embodied in all our new projects. You can see it in the Venetian holiday collection that we developed with India Mahdavi; and you can see it in the Chapeau [hat-shaped] candle with French designer Dorothée Meilichzon. Both those projects started from our iconic art deco fragrance bottles but we played with the patterns, colours and glass volumes.

Do you have an ultimate goal for the business?

To become the most desirable art of living brand – with an Italian soul, of course.

In late 1960s and 1970s New York, it was possible for a young Ralph Lauren to turn a fledgling neckwear business into a multi-billion-dollar fashion and lifestyle empire; or Belgian-born Diane von Furstenberg to transform a single jersey dress design into a global luxury label – all while partying at Studio 54 with Andy Warhol every other night. The Garment District was buzzing with designers’ orders, while fashion-magazine editors operated with unlimited budgets and American department stores from Bergdorf Goodman to Barneys were widely recognised as luxury temples, where well-heeled city dwellers returned on a nearly daily basis to restock their favourite perfumes, place made-to-measure orders for Oscar de la Renta gowns or pick up fresh flowers. Most will agree that this version of the American dream – where growth happens at lightning speed, volumes are always high and margins even higher – is well behind us.

Today the city’s creative scene paints a different picture: Barneys has shut up shop, while the likes of Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus are undergoing major consolidation. Designers are trying to come to terms with New York’s rising costs of living and the effect of potential import tariffs under the Trump administration. The Garment District has been dramatically downsized and many creatives seem to have swapped Manhattan for the city’s suburbs. The growing obstacles are impossible to ignore – as is the sense of tension on New York’s streets and subways.

Still, amid the challenges a new creative wave of designers and retailers is emerging – and working together to redefine the American dream. They might no longer aspire – or be in a position – to roll out their concepts globally, like their predecessors, but they are fostering intimate connections with customers closer to home, while setting ambitious quality and manufacturing standards for themselves and shifting the focus back to the needs of their clientele. In other words, it’s back to basics for the fashion community of New York.

“We aren’t looking to reinvent the wheel, because it wasn’t broken,” says Margaret Austin, a Brooklynite and fashion buyer, who learned her trade at boutiques such as Opening Ceremony. “We want to bring back the neighbourhood shop and service the women in the surrounding areas.” In 2022 she joined forces with her friend and neighbour Hannah Rieke to open Outline Brooklyn, an elegant boutique on Atlantic Avenue, a short walk from both their homes. The shop carries some of the world’s most in-demand luxury brands, from The Row to Maison Margiela and Dries Van Noten, alongside up-and-coming names such as Beirut’s Super Yaya and London’s Kiko Kostadinov. “It’s a mix of brands that feel very special but they’re also wearable and make sense for the women who live in this neighbourhood,” says Austin, explaining that there is always a sense of ease in the items she picks up for the shop. “These are clothes for people who walk the dog before work, who commute and go to dinner straight from the office,” she adds.

Despite the impressive designer line-up, the shop maintains a laid-back feel with its minimalist wooden furniture and cosy terrace, and the Rieke’s bike parked casually in a corner. “It was really important to create a warm space where people feel comfortable; some luxury shops are so pristine that they feel untouchable, almost like museums,” says Rieke, stressing that this space will remain the heart of the business. “We just wanted to create one excellent shop,” adds Austin. “Aside from a pop-up here and there, we don’t have huge ambitions to grow and open a million new doors. We’ve seen what aggressive growth can do to a retail business. So many great shops that worked well on a regional level have had to close down.”

This hyper-localised approach is Austin and Rieke’s answer to the traditional fashion business model, which tends to prioritise scaling up above anything else. It has also proven to be an antidote to the fatigue surrounding online shopping.

“We’re tired of doomscrolling,” says Rieke. “There is way too much product out there; it’s almost like going grocery shopping. But it seems that the pendulum is now swinging.” To that end, success for the Outline team isn’t equated to acquiring thousands of new customers but ensuring that locals keep coming back. “When a new person comes in, there’s a 95 per cent chance that they’ll become a returning customer,” adds Rieke. “We’re fortunate to have this type of response and it allowed us to keep going – [in 2024] sales were up nearly 40 per cent.”

Rieke and Austin aren’t alone: a short walk from Atlantic Avenue, you’ll find Ven Space in leafy Carroll Gardens, a meticulously put-together menswear boutique that carries best-in class names from Lemaire and Auralee to Comme des Garçons. Just like Outline, the boutique has little online presence. Instead, founder Chris Green is investing his time into getting to know local customers on a first-name basis, offering one-on-one styling appointments and reintroducing intimacy to the shopping experience.

New York’s designers, both new and established, have also been rethinking what a successful business model looks like and returning to basics. “We’ve become so provincial; our lives are really rooted here,” says Lilly Lampe, a former art critic who moved to New York from Georgia and co-founded Blluemade with her partner, Alex Robins, in 2015. After some experimentation, their label has become a go-to for corduroy and velvet “Made in New York” garments. “The proximity to the expertise of the Garment District is what keeps us creatively stimulated,” says Robins. He explains that despite rising production costs, “little city support” for the Garment District and countless attempts to move it from its historic Midtown Manhattan neighbourhood, committing to local manufacturing has allowed the brand to maintain its high standards and stand out in the crowded market. “Textile has always been the most important tool we use. Whatever we’re doing, we’re choosing the best fabrics and that’s something that retailers, such as United Arrows, have always appreciated,” adds Lampe.

Their workwear-inspired silhouettes, from double-pleated trousers to artists’ overshirts and sharp corduroy jackets, also eschew the concepts of seasonal trends in favour of a slower design approach. “It should feel as though you’re opening your grandfather’s wardrobe and picking an item,” says Robins. “You don’t know which decade it’s from; you just know that it’s a great design and you want to pick it up.”

Their limited-edition collections might seem a world away from those of uptown designers who host runway shows, partner with department stores and produce their designs in larger quantities in Portugal or Italy. Yet even some of New York’s most recognisable names have gone back to thinking locally, in order to survive the tougher market conditions. Take Marc Jacobs, former creative director of the world’s largest brand, Louis Vuitton. After many trials and tribulations attempting to scale his namesake label, Jacobs decided to focus his premium line on his home market, presenting two small collections a year and selling them exclusively at Bergdorf Goodman in limited quantities.

The new generation of designers are following in his footsteps. Jac Cameron for instance, a former designer at labels such as Calvin Klein and Madewell, launched her label Rùadh last year with the ambition of offering the most considered, sustainably made denim in the luxury market. Operating out of her chic Tribeca loft, filled with mid-century furniture and romantic mood boards of her native Scotland, she has been working on perfecting her label’s signature silhouettes (straight leg trousers with subtle pleats running down the middle and curved jackets featuring recycled hardware) and producing them in small batches in specialist factories in Los Angeles. It’s a far cry from the previous generation of American denim brands, which outsourced manufacturing to China and targeted the mass market.

“I have spent some time thinking about how to craft a brand relevant to the current moment,” says Cameron. “There’s so much out there at every level of the market, every price point. So you have to create products that are made sustainably and have lasting power in terms of the way they are structured, washed and designed. My first collection was made up of 11 pieces, made in a high-end factory in Los Angeles using less water, fewer chemicals and recycled hardware. Every element is considered and I’m very intentional about how to grow the brand.” Even if opportunities for growth are slower than they used to be, Cameron (who moved to New York for an internship with Marc Jacobs 20 years ago and never left) thinks that the city still has plenty to offer for creative entrepreneurs. “The talent you have access to is unmatched,” she says, pointing to a network of creative New Yorkers from writers, to models and stylists who started supporting Rùadh from early on. “There’s a return to more niche companies that focus on gathering smaller groups of people and building communities. New York is still a great place for this: if you think of the footprint of Manhattan, it’s actually quite small, so you always have chances to make new connections here.”

Rùadh has been seizing these chances and finding ways to grow in a more sustainable manner. For the latest edition of New York Fashion Week in February, Cameron partnered with luxury retailer Moda Operandi (its only wholesale partner) to introduce a handful of new items, including workwear-inspired jackets, skirts and “Made in Scotland” knits. “I’m not trying to produce 5,000 units of each item,” she says. “It’s all about small batches, the right partnerships and a return to craft,” she adds. “I want to meet skilled artisans doing interesting things in an industry that hasn’t been disrupted in a very long time.”

A few minutes down the road, Maria McManus, another up-and-coming name, is building her own slow-fashion operation based on near-identical values. Her eponymous label is best known for fully fledged ready-to-wear collections, ranging from breezy shirts made with organic cotton sourced in Japan to suits made from Portuguese linen and wool blazers featuring biodegradable corozo nut buttons. “The 21st century needs to be about collaborating with nature, rather than using and abusing it,” says the designer. “I would never have done this if it wasn’t about sustainable manufacturing – nobody needs another brand. People are talking about issues with inventory, synthetic micro-fibres and so forth. But few designers are actually doing anything about it.”

To that end, McManus has carved a niche for herself by developing a network of specialist boutiques from around the world that now carry her collections. Online retailer Net-a-Porter has also come on board this year as the brand’s only larger-scale partner. But even as McManus gains more global recognition via tie-ins with such platforms, she is staying focused on keeping production runs small and operating as locally as possible. In fact, much of her production still happens in New York, while her creative process, operations meetings and client appointments take place in her living room-cum-studio in Tribeca. “There’s so much happening on our doorsteps, so many New Yorkers focusing on mindful design,” she says. “It’s refreshing, after that long period [before the coronavirus pandemic] when the city went through an influx of venture-capital money and local brands expanded too quickly, becoming soulless.” She now sources furniture from a French antique dealer who lives in the same building, buys her groceries from the local farmer’s market and invests in art from a nearby gallery.

Venture-capital investments might be drying out but New Yorkers like McManus and Cameron are ready to usher in a new era, where less is more. McManus recently hosted customers at her loft for an evening of drinks, clothing try-on sessions and basket-weaving tutorials with bag designer Erin Pollard – an event that captured local designers’ renewed focus on privacy and one-on-one connections. “We’ve all become bored of big brands, big restaurant groups and mass homeware shops,” says McManus. “We’re at a point where we want to be more thoughtful about every aspect of our lifestyles: what we wear, what we read, what we put in our homes.”

It might finally be time to slow down and take stock, before forging on with the path ahead. Even for New York’s fashion-forward, high-speed urbanites.

blluemade.com; outlinebrooklyn.com; ruadh.com; mariamcmanus.com

Address book:

Menswear haven:

Ven Space

369 Court St, Brooklyn, NY 11231

Best curation:

Outline Brooklyn

365 Atlantic Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11217

For modern-day Americana:

Wythe

59 Orchard St, New York, NY 10002

Post-shopping lunch:

Fanelli Café

94 Prince St, New York, NY 10012

Designers’ favourite watering hole:

Clemente Bar

11 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10010

All-time classic:

The Odeon

145 W Broadway,

New York, NY 10013

Best interior design:

Khaite

828 Madison Ave,

New York, NY 10021

New in town:

Destree

837 Madison Ave,

New York, NY 10021

By appointment:

The Future Perfect

8 St Lukes Pl, New York, NY 10014

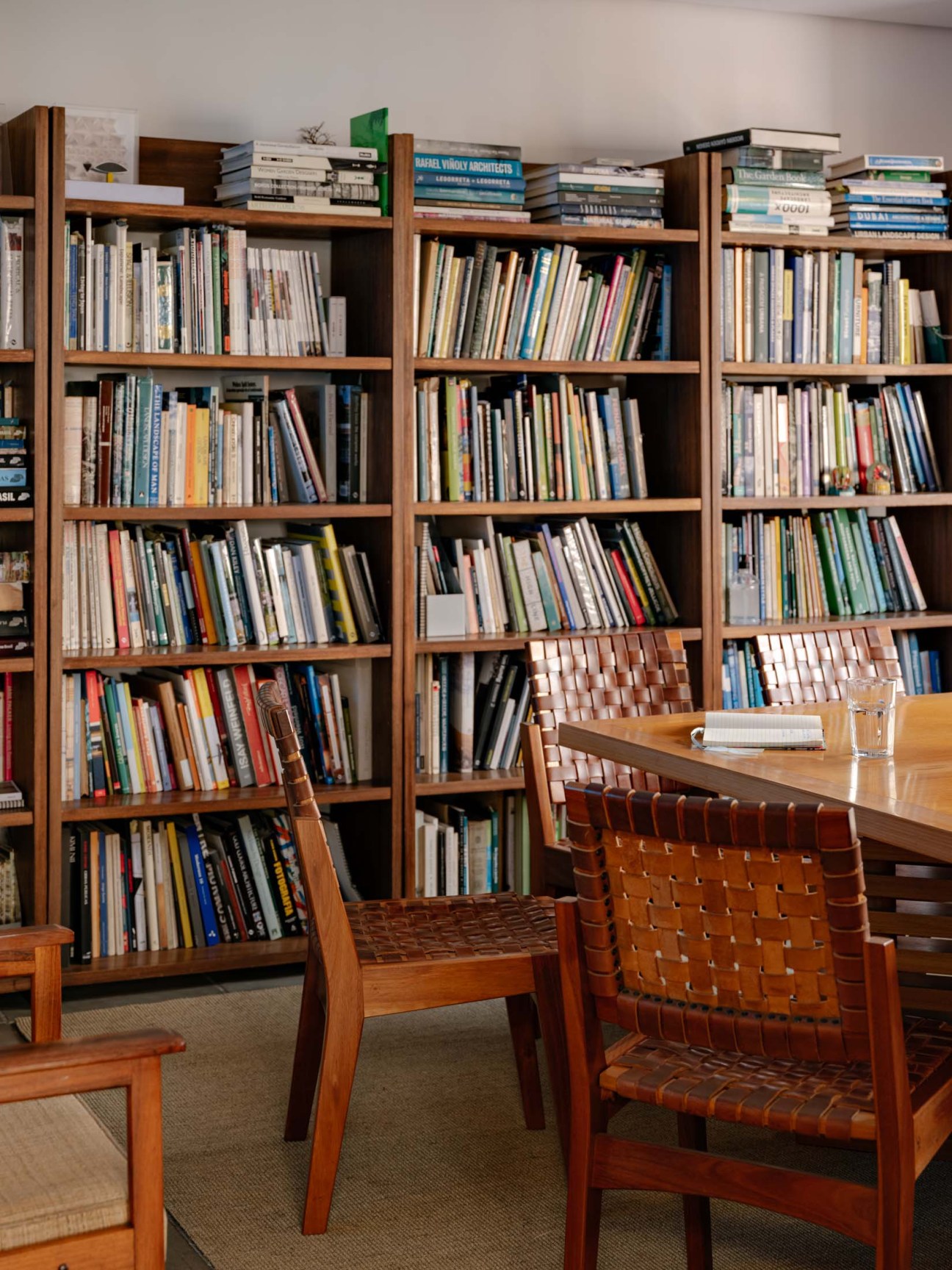

“Garden design in Brazil is still not as respected as it should be,” says Isabel Duprat. It is a balmy day in São Paulo when Monocle meets the country’s pre-eminent landscape architect, who lays bare her feelings about the state of the discipline in her home nation. She is well placed to comment on the topic. Having earned her stripes under legendary Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, Duprat collaborates with some of architecture’s biggest names today, from Marcio Kogan to Moshe Safdie. And she has a 45-year pedigree that makes her well equipped to fly the flag for the discipline in her home country.

Born in São Paulo in 1954, Duprat says that she was destined to design gardens and landscapes from a young age. “I always had this intimacy with planting and I would get all muddied up from playing on the land as a child,” says Duprat, referencing time spent at her family’s small farm in the countryside near São Paulo. Encouraged by her mother’s enthusiasm for gardening, Duprat dreamed of studying botany before ultimately pivoting to architecture. “In high-school, I said, ‘I think I will go and study architecture, so I can do landscape design.’ Brazil didn’t have a school for landscape architecture at the time.”

Despite never wanting to create buildings, Duprat graduated with an architecture degree in 1978, from the Mackenzie School in São Paulo. This institution is renowned for producing a host of multi-disciplinary talents, from modern painter Anita Malfatti to architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and Duprat made up for the lack of landscape classes by reading extensively on the subject. “At the beginning of my career, because of Brazil’s military dictatorship, it was really hard to get hold of any international books about my field of interest,” says Duprat. She also attended botany classes at the University of São Paulo. It was a self-imposed education that was soon enhanced by an internship with Burle Marx.

Often referred to as the Oscar Niemeyer of Brazilian landscape architecture, Burle Marx began changing the public’s perception of Brazilian garden design since the 1930s. His work on high-profile public projects in Brasília, particularly gardens at the Ministry of Army and Itamaraty Palace, shifted expectations away from the Renaissance and Baroque forms associated with the gardens of the former Portuguese colony. Burle Marx’s works were abstract and organic, inspired by modern art and the native landscapes. He also replaced European species with the lush tropical plants that are indigenous to the country.

Burle Marx’s effect on landscape architecture in Brazil – and on Duprat – was profound. “I was very influenced by him,” she says. “He had a richness inside him. He was, for instance, [not only an excellent designer] but also an excellent opera singer. And we once travelled to the coastal region of Angra dos Reis to research new plants in person. It was a very important time for me, where I absorbed a lot of things that I still use in my work today.”

That work stepped up a notch in 1983, when Duprat opened her garden design studio and a plant shop (she moved to her current office in 2003). Early clients were based in Rio de Janeiro and included the Marinho family – owners of Globo, the country’s largest broadcaster – and the Moreira Salles banking dynasty. Both commissioned Duprat to work on their private residences. Despite being a proud Paulistana, her experience working elsewhere and her field trips with Burle Marx expanded her conception of what good design could be.

“It freed my work,” she says. “Just looking at the Rio landscape with its mountains, I let myself go in a very positive way. Life there is lived outside, unlike in São Paulo.” Intending to share what she had learned from her work by leaving the city, Duprat hosted a garden history and landscape design tutorial at the gardening school in São Paulo’s Ibirapuera Park (which, appropriately enough, was designed by Burle Marx and Niemeyer).

Today, Duprat has clients across Brazil, from Rio de Janeiro to coastal towns in the state of Bahia. Working with architect Nathalia Fonseca and her husband, Manoel Leão – a musician and agricultural engineer who helps to co-ordinate the studio’s garden designs delivery – the landscape architect has instant name recognition in her hometown. Her namesake practice, which employs eight people, is in the leafy neighbourhood of Jardins. The office where Monocle meets to discuss her recent projects is striking, lined with sucupira wood panelling.

Like Burle Marx, Duprat’s portfolio includes everything from private gardens to public works. There are plans afoot for a park in the mountainous city of Campos do Jordão and a new roof garden for São Paulo’s Iguatemi shopping centre. The most significant recent civic commission was the Albert Einstein Education and Research Centre, a medical school in São Paulo designed by Safdie Architects: Duprat was tasked with bringing flora to the skylit atrium. Planting 149 native trees and palms, she designed the space in such a way that the greenery would survive in an environment with 50 per cent less light than outdoors. “It was a very complex project,” says Duprat. “The plants spent two years acclimatising in a vivarium [a controlled terrarium-like environment].” As with many of her projects, this was pioneering work in Brazil and it was meticulously researched through consultations with UK-based Kew Gardens botanist Sue Minter and State University of Campinas professor Rafael Ribeiro.

When it comes to working with residential architects and their clients, Duprat is particularly demanding. “When you want to have a garden, you will have to care for it for life,” she says, expressing her outlook regarding these residential projects. “I never think of a garden that my client will not tend to.” It’s an exacting vision that comes to the fore on projects such as the Ramp House. For this home, designed by Brazilian architect Marcio Kogan, Duprat created a landscape that includes fruiting, flowering and bird-attracting trees such as jaboticabas and jacarandas, as well as a pool lined with vegetation. The effect, for those who take a dip, is like swimming in the middle of a tropical rainforest. “I drew the pool as a body of water that was surrounded by vegetation,” says Duprat. “It’s almost like a flowerbed that has the ability to reflect and illuminate.”

For another property, Jardim Brasileiro (a name that simply means, “Brazilian garden”), Duprat subverted the typical residential formula by prioritising a larger front garden over creating a more private space at the back of the house. The result is a grand, verdant gesture of welcome for those arriving to the property, a dramatic experience for those entering the home. “I wanted to bring my own interpretation of Brazil’s native forests to this garden,” says Duprat. “You can’t imitate forests, of course, but I wanted to create a sensation that we experiment when we go deep into one.”

This sense of discovery is important for Duprat’s work. In another of her projects, Casa 3M, the garden has been laid out to limit sightlines and so create a sense of intrigue. “The pool in this house can’t be seen from the living room and terrace,” says Duprat. “A garden shouldn’t be unveiled in only one look. Instead, you should be encouraged to discover it through its fluidity and its empty and full spaces. That feeling of discovery is exciting and attracts us to the place. I drew inspiration from the Japanese for this, who do it like no one else.”

In all three cases, her work enhances the architecture. And in many ways, she has allowed the gardens to become perhaps the defining feature of each plot. The buildings, without the lush landscaping framing structures of concrete, glass and brick, would lack their particular visual impact. “I don’t see the work I do as an add-on to architecture,” says Duprat. “But I feel that for most in Brazil today, it is an after-thought. And it’s a shame, because the eye of the landscape architect is different from that of the architect. We work on different scales, with the sky as a reference, and that changes our perceptions completely. We work with the surroundings, with the wider landscape.”

It’s an outlook on her discipline that feels appropriate for a country so aligned with the outdoors. Its biggest cities have warm and balmy year-round temperatures and are home to plants such as bougainvilleas and bromelias, spaces that are bright and uplifting – all traits that make Brazil an appealing place for living with beautiful gardens and being more in touch with nature.

And that particular Brazilian stamp can be seen in the gardens, dense with native species, that Duprat designs. It is also part of her wider vision to fight the urban heat-island effect and add greenery to São Paulo. In fact, Duprat’s passion for vegetation is so intense that during the planning process for a home, she once requested that the structure be moved by 50cm to make space for a large native tree. “In São Paulo, the trees gives the city a dignified look,” she says. The same too could be said of her landscape architecture, whether civic or residential, whether in her hometown, in Rio de Janeiro or elsewhere across Brazil. “For me, it’s difficult to define the work I do. But there is an implicit Brazilian touch to it.”

isabelduprat.com

Offshoots

From her studio in São Paulo’s Jardins neighbourhood (meaning, appropriately, “gardens”), Duprat has been delivering some of the city’s finest residential and civic projects. Here are four of our favourite properties.

Albert Einstein Education and Research Centre

Architect: Safdie Architects

Completed: 2022

An innovative research building. An atrium through the centre of the structure features an indoor garden that spills from the roof to the basement, bringing the outdoors in.

Casa 3M

Architect: Marcio Kogan

Completed: 2020

An open-plan home made with natural materials: timber ceilings and volcanic rock floors. Its connection with the natural world continues outdoors, where a garden features greenery planted in patterns.

Ramp House

Architect: Marcio Kogan, Studio MK27

Completed: 2015

This residence in the centre of São Paulo feels as though it could be in a Brazilian rainforest. Native plants surround an outdoor pool that’s perfect for the warmer months.

Jardim Brasileiro

Architect: Andrade Morettin

Completed: 2009

A house surrounded by tiered garden beds that follow the site’s contours, blurring the lines between indoors and out. The residence presents itself as a continuous exploration of textures and colours.

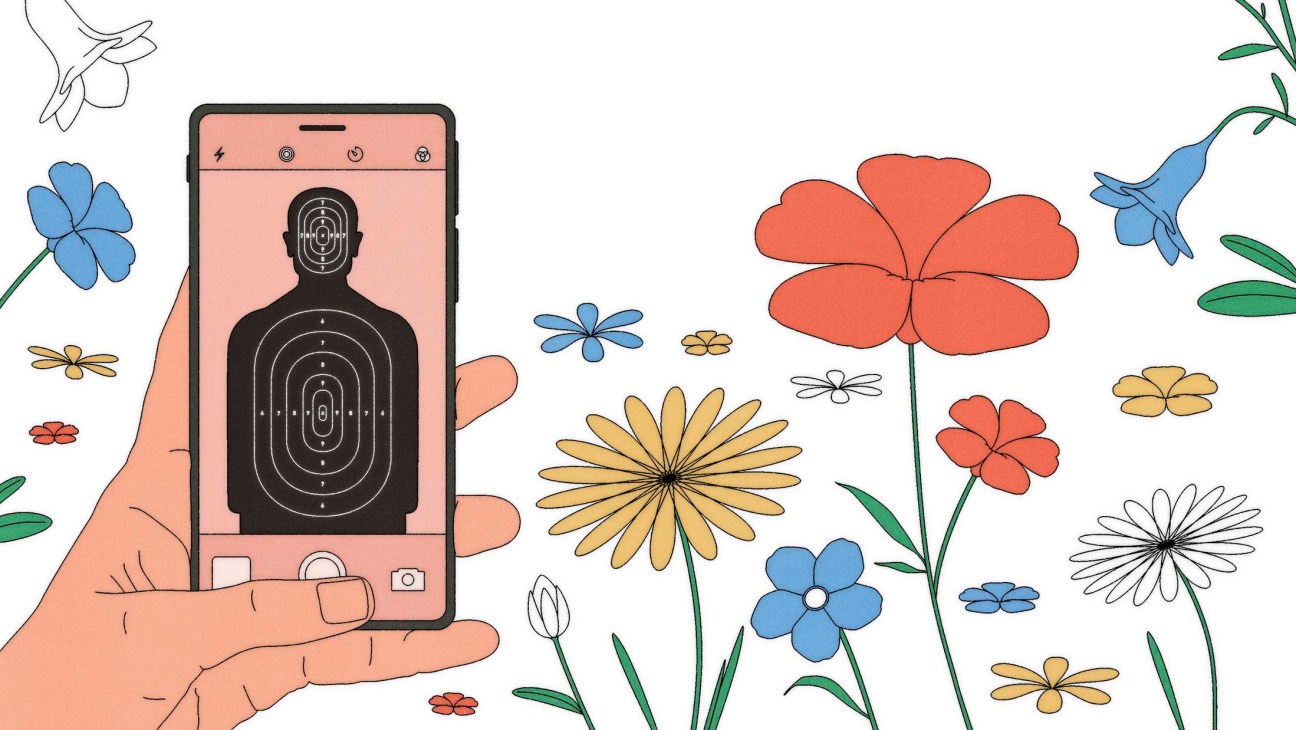

Why do we feel the compulsion to photograph or film everything that we deem important? Technology has amplified this impulse but what if we didn’t view the world through our phone screens? Studies suggest that keeping them in our pockets is a more considered way of making memories.

Maybe Kate Moss had drunk a little too much. Perhaps her high-heeled shoes got tangled up in the deep-pile carpet. In any case, the way that she walked into the Ritz in Paris one evening in autumn 2024 was less elegant than usual. Not that many were there to pass judgement. One keen observer, however, recorded the scene and posted the video on social media, giving it the title “The moment Kate Moss comes back totally drunk from a fashion show”.

There are a lot of such “moments” out there on Youtube, Tiktok and Instagram. But videos in the same style are also being shared every day in the tabloid media: the moment when a car falls off a bridge, the floodwaters rush into Valencia or a spoilt child destroys half of a Walmart supermarket.

What tends to get a little lost in discussions about all of this is why there are so many of these photos and videos in the first place. Is it simply that people were filming when something happened? Or perhaps it’s that modern, hyperactive phone users pull out their phones as soon as something exciting or unusual takes place. Like cowboys of the past who always had their gun at the ready, they instinctively pick up their device and pull the trigger, many at only the slightest provocation. Even the movement from the hip is similar: men quickly reach into their trouser pockets while women often carry their smartphones on a chain on their side like a holster so that they always have it close to hand.

More than 95 million images and videos are uploaded to Instagram every day. The number of images that never see the light of day but are taken for private purposes is likely to run into billions. Check how many you have in your own photo gallery: it is not uncommon for the total to be in the mid-five figures. Dozens of blurry concert shots, hundreds of incredibly exciting scenes from the school football match, countless pictures of food on plates – which of these would have made it into a physical photo album of the past?

One could argue that people are trying to capture the fleeting nature of life, for themselves, for their contemporaries and for posterity. After all, didn’t even our ancestors in the Stone Age leave hunting scenes scrawled on rock faces? Perhaps the impulse to capture moments has always been there. And every new medium, from drawing and writing to photography and film, has dramatically increased this tendency. In the 1980s technology-loving parents seemed to be constantly on their children’s heels with a camcorder. With the smartphone, everyone now has the ultimate recording tool in their hands.

“Every picture not taken is a moment spent being present”

Some children must have the same strange experience in their first years of life as pop stars do at concerts: they are constantly looking into a sea of camera lenses, as if the smartphone were some kind of front-end visual apparatus. If this sight had been staged in a science-fiction film 50 years ago, people would have probably shaken their heads at how stupid it looks.

If you ask anthropologists about the origin of the revolver-like “cell-phone reflex”, they will tell you that it’s less about a love of documenting things than about the human urge to “locate oneself”. At least that’s how Nicholas J Conard from the University of Tübingen puts it. “People used to carve their initials or the words ‘I was here’ into trees and park benches,” he says. “Today they take a selfie.” It’s a bit like dogs marking their territory.

In the past, postcards were used not only to send greetings, missives about the temperatures and culinary discoveries to those at home but also to call out to them, “Look where we are!” Tour guides report that nowadays younger tourists “shoot” sights with their cameras and then immediately want to move on.

In everyday life digital pins are placed and photographs are taken, as though people want to constantly reassure themselves of their own existence and, of course, excellence. The sexy, sleepy look in the mirror in the morning, the first coffee, the outfit of the day, the menu when going out – if it isn’t recorded, did it even happen?

In 2012, The Atlantic magazine published an article headlined “The Facebook Eye”. The author warned that the digital reward system of attention and likes meant that we were in danger of only focusing on potential posts. As a result, our brains would automatically check everything we experienced to see if it could be used.

Thirteen years and a few platforms later, this fear has not only been proven to have been well founded but the phenomenon has also exceeded our wildest expectations. There are influencers who stage and monetise their lives. But everyone else who posts something on social networks has also become a sort of entrepreneur, flogging mundane elements of their everyday lives, which they serve up to the attention economy. Those who experience the best, funniest, craziest things get the most approval. You just have to press the shutter at the right moment.

“The more we try to capture a moment, the more fleeting it becomes”

The shooting frenzy has a certain added value. While in the past there was hardly any direct documentation of exceptional events, today photos and videos almost always appear. In the attack at Ariana Grande’s 2017 concert in Manchester, the police were able to reconstruct the course of events primarily based on private recordings. If, in May 2020, 17-year-old passer-by Darnella Frazier had not filmed how a police officer blocked George Floyd’s airway with his knee as he lay on the ground, the perpetrator would probably never have been convicted. Conversely, hordes of such amateur reporters are increasingly blocking access for rescue workers at crime scenes. The first instinct is no longer to help but to pull out your mobile phone.

It’s not the person who isn’t filming who is missing out on anything. On the contrary: studies suggest that it’s harder to remember special moments in your life if you’re taking photos or making videos while you’re doing it. And not just because you’re less attentive but because your brain knows that you could watch it all again later. That’s why it doesn’t really “store” these moments in the first place. Researchers at Yale University also came to the conclusion that, to a certain extent, holding a screen in front of you emotionally disconnects you from what you’re seeing and the moment is experienced much less intensely. Instead of being the protagonist of your own life, you become a disinterested observer. No amount of recording, no matter how good, can change that later on and you’ll probably never watch most of it anyway.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, German philosopher Walter Benjamin put forward the thesis that an object loses its aura when it is no longer experienced directly in its original context. The same argument can be applied to personal experiences: the fashion show doesn’t feel nearly as glamorous on video. The crocodile that suddenly swam through the river in Australia doesn’t send a shiver down your spine afterwards. The child’s amazement at its first steps can be watched a hundred times but never experienced in the same way again.

The more that we try to capture a moment the more fleeting it becomes. All recordings of it seem empty. Not to mention the time that goes into it. You don’t just take one picture but several. Then you edit, process and publish it.

Because modern smartphone users love taking part in challenges that they are then asked to record and share via video, here is a challenge for the coming weeks. Let’s call it “Let it go!” It’s about not posting anything, not recording anything or taking photos – just watching the children’s sledding race, enjoying a meal with your loved ones phone-free and not singing along to your favourite band’s performance while clutching your device.

Let’s be honest: nobody is really interested in other people’s concert clips. Even “likes” for plates of oysters or cheese fondue videos are at best friendly handouts. Every picture not taken is a moment spent being present. In return, it might stay on that other, human hard drive for a little longer.

About the writer:

Wichert is a journalist and fashion writer at the Süddeutsche Zeitung. A version of this article was first published in German in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

In European diplomacy, few jobs are more demanding than the post of Serbia’s foreign minister. Its holder must manage relations with several neighbours that the nation has fought against in recent history, one of which – Kosovo – it refuses to recognise as a sovereign state. For related reasons, Serbia looms in the Western imagination as somehow not quite one of us. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, of which it was a part until 2003, was the only European country to have engaged in a hot war with Nato. Meanwhile, Belgrade maintains obstinately friendly relations with Russia.

Throughout his career, Marko Djuric, Serbia’s 41-year-old foreign minister, has had to deal with such challenges. Before being appointed to his current position last May, he spent more than three years in Washington as Serbia’s ambassador to the US. Before that, he was the director of Serbia’s Office for Kosovo and Metohija, which oversees the country’s turbulent relations with its reluctant former constituent. On one visit to Kosovo in 2018, Djuric was unceremoniously arrested and deported after local authorities claimed that he had entered without permission.

Prior to that, he was a foreign-policy advisor to Serbia’s then president, Tomislav Nikolic. Unlike the current president, Aleksandar Vucic, who served as minister of information under Slobodan Milosevic, Djuric has no ties to the regime culpable for the wars that destroyed Yugoslavia during the 1990s. Quite the opposite: as a teenager, he was active in the Otpor! (“Resistance!”) movement, which was crucial to the overthrow of Milosevic in October 2000.

Serbia is now convulsed by remarkably similar-looking demonstrations. In November the collapse of a concrete canopy at Novi Sad train station killed 15 people. There have since been huge and recurring protests. Serbia’s government has seemed uncertain how to respond. The prime minister, Milos Vucevic, resigned in January – but his deputy, Aleksandar Vulin, has suggested that the protests are being stoked by Western intelligence agencies, an echo of the Milosevic-era complaint about Otpor! In a corner office at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Belgrade, an aide tidies away a “Make America Great Again” cap before Monocle sits down with Djuric to discuss the current protests, Milosevic, Ukraine, Donald Trump and more.

What drew you to politics?

My grandfather was involved in Yugoslav politics and my great-grandfather’s brother [Nikola Pasic, former prime minister of both Serbia and Yugoslavia] was too. So it was natural for me to be interested. Growing up in Belgrade in the 1990s, you couldn’t escape what was going on. I was born in the capital of a country of 23.5 million people, covering more than 255,000 sq km. Then it became smaller and smaller, until it was the capital of a country of about seven million people.

As a teenage rebel, did you imagine that you would be sitting where you are now?

I certainly didn’t. But we had big dreams for our nation. Those years were a crucial moment in Serbian history. We were able to introduce serious democratic reforms after a difficult decade in which we not only lost our reputation but suffered tremendous losses – in terms of territory, people and the economy. It all went very wrong during the 1990s. But on 5 October 2000 [when protests forced Milosevic to resign], the people said, in a loud, clear voice, “We do not accept the direction that the regime is taking us and want to belong to a different type of community of nations.”

Do the current protests in Serbia remind you of Otpor! at all?

Apart from the fact that both are protests, I can’t say that I see any other similarity. The protests of 2000 were the culmination of a nationwide struggle for democracy. They were driven by our desire to free our country from a regime that had isolated us from the international community and to build a bright future in a new, democratic society – which is what we have today.

Today’s protests originated as a public expression of grief over the tragic incident in Novi Sad; this was coupled with calls for accountability. So the context is quite different. Centred on four key student demands, these protests have brought issues such as upholding the rule of law, fighting corruption and strengthening our institutions into our focus. The government has addressed these concerns within a democratic framework and has fulfilled the students’ demands.

Which aspect of Serbia’s foreign policy are you prioritising?

We need to break free from the paradigm that we inherited from the 1990s and resolve our political problems. These include our difficult relations with some of our immediate neighbours and the relationship between Belgrade and Pristina. It’s the only way for us to turn the Balkans into one of Europe’s engines of economic growth, which I believe is possible. For us to be even more successful, we have to create a friendly environment for Serbia. As foreign minister, I view this as my primary task: to make new friends for my country and ask people across Europe and beyond to take a fresh look at us.

Do your neighbours still have fears and suspicions about Serbia because of what happened in the 1990s?

Yes. The break-up of Yugoslavia didn’t unfold like Czechoslovakia’s. There are still many families suffering as a result of those wars, as well as unresolved issues, including missing persons. It’s our duty to establish, where they do not exist, working groups to tackle these things. But we need two tracks: one for resolving those issues and closing open wounds, and the other for looking towards the future. We have to forge better connections between our countries. We have hard borders in our region that divide communities and families, and prevent business. Think of the number of hours that trucks spend a year on the borders between Serbia and Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia and Croatia: it probably adds up to thousands of years.

“No rational Serbian politician would support any policy that would involve attempts to forcefully change borders”

Do you still need to reassure your neighbours that Serbia is happy with where its borders are now?

A quarter of a century ago, Serbs renounced a regime that was involved in very wrong-headed attempts to amend regional borders and we were burned by this. No rational Serbian politician would support any policy that would involve attempts to forcefully change borders.

Does this thinking apply to Kosovo?

Our relationship with Kosovo is very specific. It unilaterally declared independence in 2008, almost a decade after the war in 1999, in which Serbia also suffered greatly.

The ruins across the street are of the Yugoslav Ministry of Defence building, aren’t they?

Yes. Nato bombed it in 1999. But just a year later, Serbs embraced and elected a pro-EU, pro-Nato government. Then, in 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence without the participation of Kosovo’s Serbs. It was completely outside the Constitution of Serbia and outside the scope of the UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which ended the hostilities in 1999. The resolution stipulated that Kosovo should be an autonomous province within Serbia, with the highest degree of autonomy to be determined through negotiation. This not only resulted in a new political problem in our region but also created political openings in Serbia for various malign influences.

If you ask Kosovo’s current government what it wants – and I’ve interviewed its prime minister, Albin Kurti, several times – the answer is simple. Kosovo wants to be a country like any other. Does Serbia have a preferred end point now?

We’re working hard to change the relationship between Serbs and Albanians. Relations between Serbia and Albania have helped a lot in recent years. With Albania and North Macedonia, we created a single labour market that has been in effect since March 2024. It shows that things can be different. Last summer about 118,000 Serbs spent their holidays on the shores of Albania. It’s no longer a conflict between Serbs and Albanians.

But what would a settlement look like?

We need a pragmatic solution that will be a win-win for both Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo. Serbs are the majority in 10 out of 38 municipalities in Kosovo. That’s what remains of the Serbian community, which has suffered very greatly, just as Albanians have. We need a compromise that will address the questions of status and territory in a way that won’t leave either side entirely frustrated. We’re not setting any red lines as to what the final outcome of the arrangement might be.

Has there ever been any talk along the lines of: just let Kosovo go and President Vucic and Prime Minister Kurti can share a Nobel Peace Prize?

We’re not in the business of doing things that are personally profitable. For Serbs, Kosovo and Metohija aren’t just about territory. There are four Unesco World Heritage sites of the Serbian Orthodox Church [in Kosovo], which, by the way, has been around since 1219. For Serbs, it’s like a spiritual cradle. Many of our medieval kings and queens ended their lives as monks in the monasteries that they built in Kosovo. So it’s complex. It’s something that deeply touches the emotions of every Serbian.

Serbia has been an EU candidate since 2012. Your office is decorated with the bloc’s flag, as well as the Serbian one. Are you still serious about joining it?

It’s a key priority. By 2027, Serbia will fully complete all of the reforms required for membership. Even now, Serbia is doing far better economically than many countries that are already members. Our debt-to-gdp ratio is 46 per cent, while the Eurozone average is more than 90 per cent. The IMF has projected that we’ll have a growth rate of 4.1 per cent this year. The Eurozone’s projected growth rate is 0.7 per cent. Serbia can contribute a lot to Europe – not just in terms of the economy but also when it comes to culture and our geopolitical position. We are at the crossroads of civilisations. We are in the middle of southeastern Europe and have a vast network of connections and friendships with countries just beyond our region.

What is your position on Russia and Ukraine? Serbia has declined to participate in sanctions against Russia. But you’ve sold Ukraine a lot of ammunition – at least, through third parties. Whose side are you on?

Serbia has a clear position of unambiguous support for Ukraine’s integrity and sovereignty in the entire territory of the country – including Donbas, including Crimea. My first guest here after I was appointed to this role was Ukraine’s former foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba. Since then we have also met its current foreign minister, Andrii Sybiha. Serbia has consistently voted in the UN and in the OECD to support Ukraine’s territorial integrity and condemn any actions that undermine this. I should also mention that Ukraine supports Serbia’s territorial integrity in the question of Kosovo and Metohija. However, our relationship with Russia is somewhat different, both historically and currently, than with some other European countries.

Why is that?

We have some interests – including the question of Kosovo and Metohija – for which the Russian Federation provides support at the UN Security Council, alongside the People’s Republic of China. Sometimes, people have used this specific situation to criticise Serbia. It’s easy not to look under the surface and come to the conclusion that there’s something more to our relationship with Moscow. I’ve read conspiracy theories linking Serbia to Russia in ways that would mean that we ostensibly support what it is doing in Ukraine. But we aren’t supporting that war in any way.

Could Serbia be an interlocutor? Have you had any direct contact with Russia since taking this job?

I haven’t met my Russian counterpart and haven’t been to Moscow yet. I can say that we have been approached by various actors internationally with ideas to act as intermediaries. But, for the time being, we are doing everything we can to help with the humanitarian needs of the people of Ukraine, and we are focusing on maintaining our position and our interests, because this is not simple in the current circumstances, as you can imagine.

“The Balkans can’t be Europe’s blind spot while Russia and Trump-era politics loom over the continent”

With Trump back in the White House, do you think that things will be easier? I noticed a Maga cap on the bookcase when I arrived and I doubt that many European foreign ministers own one of those.

In the coming months we will need more countries that are able to talk to all sides. Being ready for conversation while taking a principled stance is what I believe will be most helpful for Serbia. As for Trump, if you look at the opinion polls in Europe, you’ll see that Serbia probably has the biggest number of his supporters per capita. Even many liberals here are pro-Trump. Their reasons aren’t ideological. It’s to do with the fact that it was the Democratic Clinton administration that bombed Serbia in 1999, bombed my hometown of Belgrade. Unfortunately, this is still a feeling that is out there but Serbia has made tremendous steps forward in its relationship with the US. People in Serbia would support any politician who is ready to take a fresh look at our country and establish a new type of relationship. We are moving closer to the US in many ways and are hopeful about seeing its new president visit Serbia.

How much of a burden is the recent past? Do you feel obliged to maintain some grievances for domestic political reasons? For example, you recently complained that the UN-designated day of recognition for the Srebrenica massacre of 1995 [in which some 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were killed] only memorialised one group, rather than the 100,000 victims of the wider conflict.

Unfortunately, many among the political elites and the wider public in the West haven’t been exposed to new developments in the Balkans so I often need to talk about all of the things that have changed. Among these is our mindset. In the 20th century, many of us were focused on ideological, territorial and identity issues. Now we are concentrating on growth and building up our infrastructure. Ethno-nationalism in its malign form is still out there but it’s not a prevailing current of Serbian politics – or even regional politics, for that matter.

Much of the rhetoric of Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska [one of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s two constituent entities, predominantly inhabited by Serbs], sounds like ethno-nationalism in its malign form.

I speak for the Republic of Serbia. We are committed to regional co-operation and stability. Serbia firmly supports Bosnia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. It also supports the Dayton Peace Agreement, which means that we support the territorial integrity of Bosnia but also the [autonomy] of Republika Srpska and the Federation [of Bosnia and Herzegovina].

So you’re absolutely against any declaration of independence by Dodik?

I’m against anything that violates the Dayton Peace Agreement, including that.

Is your overall contention that prosperity is the cure for ethno-nationalism?

Economic prosperity and connectivity are prerequisites but we also need to emancipate ourselves to a sufficient level to be able to preserve our national identities and cultures without hating each other. We might not be there yet but we’re getting close.

When you talk about the idea of the Balkans without internal borders, with national identities preserved yet subsumed in mutual self-interest, it sounds like you’re describing Yugoslavia.

We aren’t aspiring to recreate Yugoslavia because it failed miserably in previous generations. We want to create a truly European Balkans that will enable young people to live their dreams in their own region, instead of leaving for Western Europe, the UK or the US. And I believe that this is achievable in our generation.

In February, Greece announced a 12-year €28bn modernisation of its armed forces that will include the acquisition of 20 fifth-generation F-35 fighter jets, a sensor network for underwater threat detection and the construction of a comprehensive air, missile and anti-drone system dubbed “Achilles Shield”, built in partnership with Israel. The plan also allocates about €2.5bn a year to the Hellenic Armed Forces, meaning that Greece will potentially exceed the more than 3 per cent of GDP it currently spends on defence.

Countries such as Poland have been singled out for walking the talk on defence at a time of heightened security concerns across Europe. But Greece is rarely mentioned in the same sentence, even though it has the third-highest defence expenditure of European Nato members as a percentage of GDP. For decades, Athens, like many European nations, relied on the US to guarantee its security. Its mutual defence co-operation agreement with Washington, signed in 1990, grants American forces access to Greek bases.

“Athens’ military push comes at a time when it’s also trying to burnish its diplomatic credentials”

But with uncertainty over Washington’s commitment to Europe, Athens is recalibrating. It has become one of the EU’s most vocal advocates for defence autonomy, pushing for looser fiscal constraints to allow members to bolster their own security without breaching the EU debt ceiling. Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek prime minister, has suggested a similar system to Achilles Shield to cover the whole continent. Athens’ military push comes at a time when it is also trying to burnish its diplomatic credentials. In January, Greece began a two-year term as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council and foreign minister Giorgos Gerapetritis has been active, attending bilateral meetings concerning the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. During uncertain geopolitical times, Athens is aiming to have its voice heard above the panic.

At the back of American designer Giancarlo Valle’s New York studio, there’s a room that looks as though it could be a Wallace and Gromit film set. Shelves are lined with maquettes from architecture and interior-design projects, which include miniature furniture pieces such as thumb-sized lampshades and chairs no larger than hens’ eggs.

For Valle, who trained as an architect, these small-scale buildings and furnishings are integral to his practice, which encompasses architecture, interiors and the decorative arts for residential and commercial projects. His studio has designed lofts in New York, villas in St Barths and residences in Mexico City. “We work on a lot of interior architecture, so using models is important,” says Valle. “They help you to understand the proportions or height of something – both essential when it comes to composition.”

The team spends hours crafting and then rearranging the sculptures within the maquettes. The studio has acquired a 3D printer that renders products in materials such as aluminium and wood. But sculpting pieces by hand from clay is still a large part of the creative process. “It’s fun,” says Valle, picking up a hand-moulded chair.

“As a creative person, one of the most rewarding things that you can achieve is an element of surprise,” he says. “There is a lot of planning in architecture, so you know what you’re going to get. But this process also allows you to do unexpected things,” he adds, holding up a green couch about the size of a deck of cards. He places it back on the shelf, next to a miniature coffee table. “Models force you to edit your work. With a computer, you can make objects as big or as small as you want. But with models, you actually have to make decisions.”

The sculptures also act as a kind of visible archive that the team can tap in to at any point. “Having them in the space is a big part of the way we work,” says Valle, who often uses old models to inspire new projects. “We take ideas and repurpose them,” he adds, looking around the room at the various models, which resemble unfinished dolls’ houses. “There’s no formula to it. Sometimes we start on a computer and other times we start on a model but the idea is to keep things visible.”

Monocle follows Valle to the main room, where an employee is painting a maquette with squiggles and half-moon shapes in shades of black and gold. We then travel downstairs to a studio with a long, crafting worktable. Creating models in this way ensures that the team comes up with innovative design ideas that haven’t been perpetuated online. “It’s our remedy for internet algorithms,” says Valle. “Everything is digital now and everyone sees the same things. There’s no way to break out of that cycle unless you create your own analogue algorithm,” he says, gesturing to the shelves lined with objects and tools. “A generation of work is being created that is just referential; a recycling of ideas,” he says. “You have to invent your own world.”

Canadian author Éric Chacour’s writing reads more like poetry than prose. In his award-winning debut novel What I Know About You, he reimagines the tragic tale of Romeo and Juliet through the character of Tarek, a Levantine Egyptian man living in 1980s Cairo whose life is turned upside down by a fateful encounter. For Chacour, writing is the medium he uses to translate a wide-ranging passion for the arts that also includes music and theatre. “I always say I wrote a novel because I couldn’t play the piano,” he says.

Born in Montréal to Egyptian parents who migrated to Canada in the late 1960s, Chacour grew up hearing stories about the community they had left behind. “They were part of a small Syro-Lebanese community in Cairo. They were Christian and often learned French before learning Arabic. It was a bubble within Egyptian society.”

Setting his novel in late 20th century Cairo allowed Chacour to dive deeper into his heritage. “Writing this book was a way to connect my parents’ Egypt with the very different Egypt I saw when I visited many years later for Christmas or summer holidays,” he says. His father’s job also took the family between Montréal and Paris.

It was as a teenager that he discovered his passion for literature through writing song lyrics. The words of singer-songwriters such as French artist Jean-Jacques Goldman and Belgian poet Jacques Brel made their way into his novel. “I recently re-listened to ‘Le Coureur’, a Goldman song I hadn’t heard in a long time and stopped when I heard his lyric, ‘Je suis étranger partout’ [I’m a stranger everywhere],” he says. “It’s a central theme in my book and I realised that’s where I probably got the idea for it.”

Originally written in French, his debut novel received accolades from the Francophone literary world, including the Prix des Libraires (awarded by booksellers), the Prix Femina des Lycéens (an accolade given by a jury comprising only adolescents) and most recently the Prix France-Québec, a Canadian literary award. The novel has been translated into 15 languages.

For Chacour, collaborating with the translators was a process of rediscovering his own work. “It forced me to verbalise my intentions, some of which had been purely subconscious,” he says. “My English translator would pick two sentences from the original text and would notice similar structures such as the same number of syllables and rhyming words. There’s a distinctive poetic construction that I hadn’t fully realised existed.” The English version earning a shortlist nomination for the 2024 Giller Prize, a Canadian award for English language fiction, is a testament to the translator’s success in conveying not only the words but the melody of Chacour’s story.

Most recently, What I Know AboutYou has been picked up for a theatre adaptation in Québec with Canadian artistic director Olivier Arteau taking on the task of bringing the author’s words to the stage. For Chacour, this new translation is the occasion to explore another dimension of his novel, mixing different art forms to create an even more meaningful experience.

It’s also an opportunity to settle back in Québec after a year touring the world to promote his book – and tackle his second novel. “I’m ready to go back to the solitude of my keyboard,” he says. “For a lot of authors, writing is a painful thing. For me, it’s a soothing process.”

The CV

1983: Born in Montréal.

2007: Graduated from the Université de Montréal in applied economics and international relations.

2013: Starts working on his first novel.

2023: Publishes What I Know About You. Later that year, Chacour is warded the Prix des Libraires and the Prix Femina des Lycéens.

2024: Awarded the Prix des cinq continents de la Francophonie.

2025: What I Know About You is tapped for a theatre production.

Art

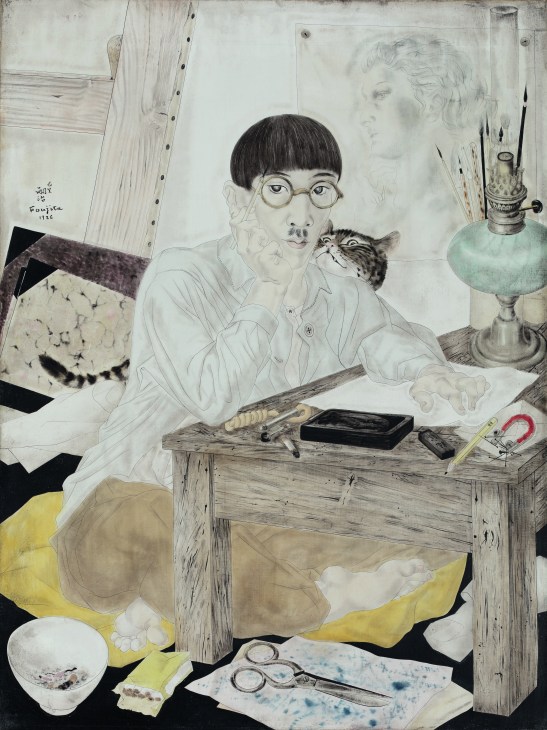

City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris 1920s–1940s

National Gallery Singapore

Between the two world wars, Paris was a playground for artists such as Picasso and Dalí. This group show reframes the era from an Asian perspective, spotlighting talented painters, such as Georgette Chen and Amrita Sher-Gil, and Paris-based designers and furniture makers from Asia. Often sidelined at the time, this overdue corrective explores their influence on Western art.

‘City of Others’ runs from 2 April to 17 August 2025

Paula Rego and Adriana Varejão: Between Your Teeth

Centro de Arte Moderna Gulbenkian

Varejão is one of Brazil’s leading contemporary artists, famed for using cracked Portuguese tiles as a visual metaphor for subjects such as colonialism and religion. She co-curates this two-hander, drawing parallels with the work of Paula Rego, who shared a desire to tackle taboos.

‘Between Your Teeth’ runs from 11 April to 15 September 2025

Photography

Kunié Sugiura: Photopainting

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

A trained photographer, Sugiura’s first multimedia works happened by chance in 1967 when she moved to New York and couldn’t find a darkroom. Coating canvases in photo emulsion started a lifetime of experimentation. The artist has oscillated between the soft expressiveness of her brush and the focus of her lens ever since.

‘Kunié Sugiura’ runs from 26 April to 14 September 2025

Books

Children of Radium

Joe Dunthorne

In this memoir, poet and novelist Joe Dunthorne investigates the life of his great-grandfather Siegfried, a Jewish scientist who worked in Germany between the wars developing, among other substances, radioactive toothpaste and poison gas. Siegfried wrote a near 2,000-page memoir, which Dunthorne’s father called “a bit of a slog”. By contrast, Children of Radium is anything but: a funny and moving family history that troubles even as it entertains.

‘Children of Radium’ is published on 3 April

The Accidentals

Guadalupe Nettel, translated by Rosalind Harvey

Nettel, one of Mexico’s most well-regarded authors, returns with a collection exploring the ways in which ordinary lives can turn upside down. Sometimes these changes, such as the one described in “The Pink Door”, are brought about by magic. Other stories, such as the brilliantly menacing “Playing with Fire”, suspend us in a space somewhere between realism and horror-tinged fantasy.

‘The Accidentals’ is published on 10 April

On the Calculation ofVolume, Books I & II

Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara J Haveland

The first two books of Danish writer Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation ofVolume are published simultaneously. They follow Tara, a bookseller, as she lives repeatedly through the same November day. If the conceit isn’t original, the beauty and philosophical heft that Balle brings to it is.

‘On the Calculation ofVolume’ Books I & II are published on 10 April

TV

Government Cheese

Apple TV1

David Oyelowo, alongside his wife and producing partner Jessica, signed a first-look deal with Apple TV+ after his work on their series Silo convinced him of the streamer’s commitment to originality and artistic integrity. Their collaboration, surrealist comedy Government Cheese, features Oyelowo as a 1960s family man intent on grabbing his slice of the American dream.

‘Government Cheese’ is released on 16 April

The Eternaut

Netflix

One of Argentina’s most celebrated literary works, The Eternaut is a dystopian comic series about the survivors of a mysterious, toxic snowfall, now left to battle new oppressors. It proved unexpectedly prescient for its writer, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, who was disappeared by the country’s military dictatorship in 1977. Now, a Spanish-language adaptation shot in Buenos Aires hopes to honour his legacy.

‘The Eternaut’ is released on 30 April

Music

Slipper Imp and Shakaerator

Babe Rainbow

Listening to Babe Rainbow will immediately transport you to their native Rainbow Bay in East Australia. This album was recorded in a warehouse on a banana farm and is full of their trademark sunny acid-pop sounds. The breezy “Long Live the Wilderness” hides the track’s theme of the loss of innocence. Another highlight is “Like Cleopatra”, featuring fun synth-funk beats.

‘Slipper Imp and Shakaerator’ is released on 4 April

Jesucrista Superstar

Rigoberta Bandini

This is Spanish singer Paula Ribó González’s follow-up to her successful 2022 record La Emperatriz. The 22-track album traverses from the danceable electro pop of “Kaiman”, which sounds like it could be a winning Eurovision entry, to the poignant single “Pamela Anderson”, a tribute to the American actress. A big summer tour across Spain is on the horizon.

‘Jesucrista Superstar’ is out now

Music Can Hear Us

DJ Koze

The German DJ and music producer returns with an album released on his own label, Pampa Records. The cosmic-inspired record has an A-list set of contributors, including Damon Albarn on “Pure Love” and Ada and Sofia Kourtesis on “Tu Dime Cuando”. Progressive house track “Unbelievable” is a highlight, as is the otherworldly cover of the 1983 iconic summer hit “Vamos a la Playa” by Italian duo Righeira.

‘Music Can Hear Us’ is released on 4 April

Film

The End

Joshua Oppenheimer

Having made The Act of Killing, one of the most inventive documentaries in memory, and followed it up with further acclaimed non-fiction work, it would have been easy for filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer to remain in his comfort zone. Instead, he has defied expectations by returning to cinemas with an audacious post-apocalyptic musical starring Tilda Swinton and Michael Shannon as the heads of a family clinging to their privilege after an extinction-level event.

‘The End’ is released on 28 March

The Most Precious of Cargoes

Michel Hazanavicius

The first animated feature to compete for the Palme d’Or since Waltz with Bashir in 2008 takes on similar themes of war, dehumanisation and trauma. In this case, a fairy-tale retelling of the Holocaust centres around a baby abandoned just outside Auschwitz. It’s a lyrical fable that includes the perspective of those who enacted these horrors – and some who defied them.

‘The Most Precious of Cargoes’ is released on 4 April

The Amateur

James Hawes

In troubled times, escapism and familiarity can be attractive, so the timing of The Amateur could not be more perfect. James Hawes’ spy thriller is based on the 1981 Robert Littell novel, which was previously adapted for the screen starring Christopher Plummer. It has now been reimagined with Rami Malek as a CIA operative who goes on a quest to avenge his wife’s death.

‘The Amateur’ is released on 11 April