Bread is serious business in France. Some six billion baguettes are sold here every year – most baked in the ovens of 35,000 independent boulangeries, according to the Confédération Nationale de la Boulangerie et Boulangerie-Pâtisserie Française. On average, each of these shops serves some 300 customers a day.

France is also obsessed with Japan: it is the biggest overseas market for manga and Europe’s largest consumer of sushi. Japanese entrepreneur Michio Hasegawa and his business partners put two and two together and gambled on selling shokupan, the pillowy Japanese milk bread, to a hungry Parisian market.

On Rue Rambuteau in Le Marais, Carré Pain de Mie specialises in feather-light milk bread loaves and Japanese sandwiches. Classic sandos such as the creamy tamago egg filling and the tonkatsu (fried pork) are just some of the Western-influenced yoshoku classics that arrived in Japan following the US occupation in 1945. Its sando du jour runs the gamut from teriyaki chicken to foie gras terrine to show off the culinary confluence of two food-obsessed nations.

“The success wasn’t immediate,” says Haruki Ishiguro, the head baker at Carré Pain de Mie of the restaurant that opened in 2017. “But little by little we started to get more and more customers.”

When monocle visits, the crowd is as eclectic as the sando variations on offer: there’s a Japanese customer eager to take home a fluffy hunk of comfort food, wedged between a group of tourists and a family waiting for a table. In the pale-wood dining area, couples nibble shokupan crusts, offered as a side alongside the crustless cuboid-shaped sandos.

Carré Pain de Mie isn’t the only shokupan specialist whose fortunes are rising. At L’Atelier Sando on a quiet street in the 18th, lunchtime patrons of every stripe are similarly hungry: some in designer clothes, others in hard hats and high- visibility vests.

Louis Ricard opened L’Atelier Sando after taking over his parents’ French bakery when they retired. The site has retained a French touch but the cooking now is Asian-inspired and the window displays feature Japanese melon cakes and distinctive and colourful lychee and yuzu Ramune soda bottles.

“I worked in Japan and discovered sandos there,” says Louis, a former chef at l’Hotel Particulier Montmartre. He says that the pandemic’s shake-up of the restaurant industry made him want to reclaim the family bakery and strike out on his own with something less tested. “My brother is also a baker and pastry chef, so we recovered all the equipment here and started making sandos in-house; everything, including the bread.”

Other food entrepreneurs also saw the opportunity to follow in Carré Pain de Mie’s footsteps at that time. “My business partner already had two izakaya restaurants in Paris,” says Benjamin Trémoulet, co-owner of Soma Sando, another post-pandemic addition to the sandwich scene, referring to Japan’s version of an informal pub serving small plates. “During the lockdown, izakayas were not successful because small plates don’t travel well so didn’t work as a takeaway option.”

Going from izakaya to sandos proved so successful that Trémoulet and co-founder Marwan Rizk decided to open a cosy, wood-clad site on the southeastern corner of the Jardins du Luxembourg. Its best-seller? An award-winning Tori Sando, a karaage chicken sandwich with tartare sauce, crisp carrot and cabbage, and sharp pickles.

For other chefs, the informality of the simple sando is democratic and yet offers some space to be creative with the culinary similarities and differences between Japan and France. Chef Walter Ishizuka, who trained under Paul Bocuse and had a decades-long career in fine-dining restaurants across the world, opened Yabaï Sando near the carrefour de l’Odéon. “My father is Japanese and my mother is French,” Ishizuka, who grew up in Lyon, tells monocle over coffee at his dark-walled restaurant bedecked with paper pendants. “At school I didn’t have jambon-beurre sandwiches in my picnics; I had white-bread egg sandwiches. There’s a [personal] history there that I wanted to revisit.”

Ishizuka’s take on the sando expands beyond his childhood staple. The combination of his Michelin-starred-restaurant experience and technical mastery mean decadence in the form of his Wagyu beef sando and experimentation seen in products including his black sando bread coloured with burnt vegetables.

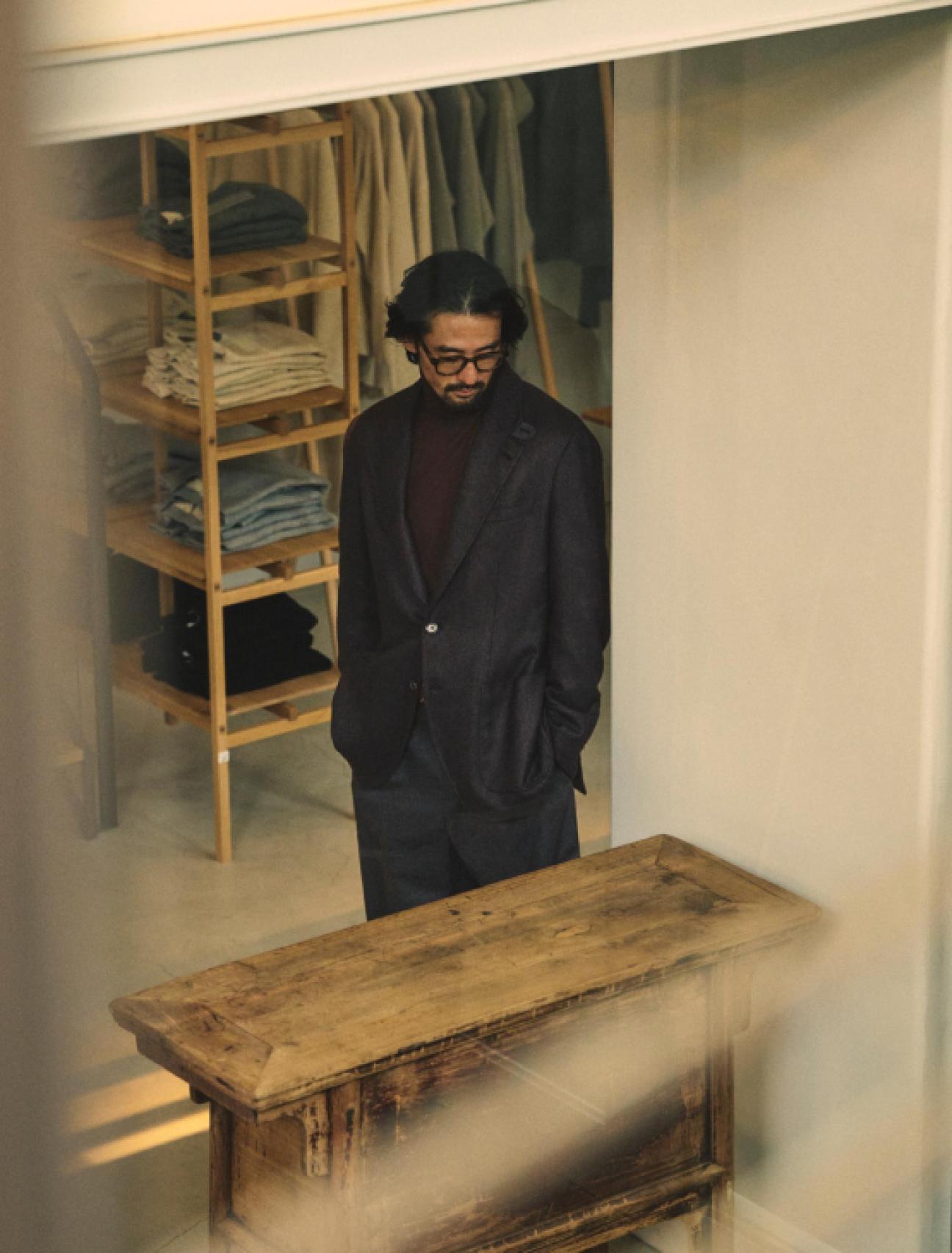

Success for these sorts of restaurants is never assured. “In the beginning, I doubted whether it could be accepted by French people,” says another sando aficionado, Kaito Hori, who opened Benchy on Rue du Cherche Midi. The former fashion designer still tries to bring together his branding experience with alluring shoots and visuals but it’s the quotidien joys of running a bakery that he enjoys most. “We’re happy because we have so many regulars coming nearly every day to have sandwiches.”

As with every food movement and seemingly fresh idea, many see echoes of older trends and more entrenched customs in Paris’s embrace of the sando. “The success is first and foremost about the enthusiasm of France’s younger generation for Japan,” says Michio Hasegawa. But, says the septuagenarian, there’s nothing entirely new in it. “It’s the same enthusiasm you saw for France among the youth of my generation in Japan back in the 1960s.”

Get a slice of the action here:

Carré Pain de Mie

5 rue Rambuteau 75004

L’Atelier Sando

169 rue Championnet 75018

Sôma Sando

62 rue de Vaugirard 75006

Yabaï Sando Odéon

3 rue des Quatre-Vents 75006

Benchy

50 rue du Cherche-Midi 75006

In a nondescript industrial park on the outskirts of Canberra, the future of warfare is being redefined. It might be thousands of kilometres from any active conflict but the whirr of movement on the warehouse floor at Electro Optic Systems (EOS) tells its own story. EOS develops and manufactures a range of military and space-related technology but in recent years has become known for one thing: anti-drone systems. Its pre-eminent status in this nascent field has been underlined by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, where more than 100 EOS products are in use every day. As drones become cheaper and more deadly, nations around the world are racing to secure technology that can counter the threat, meaning that EOS is suddenly in high demand.

On the factory floor, dozens of anti-drone systems are packaged up ready to be delivered to customers, while others undergo testing to ensure that they can operate continuously in the most challenging of conditions: some are in temperature chambers at a balmy 60c, while others are set to a frosty minus 32c. In the early 2000s, the US was the only military with high-quality drone technology – the Predator unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), which was deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. But since then, as the technology has proliferated, its costs have plummeted. “Now it’s an asymmetric form of warfare,” says EOS’s CFO Clive Cuthell, whose thick Scottish accent belies his 30 years in Australia. “You can spend $1,000 on a drone and attack an asset that costs $10m, $100m, even $1bn. You no longer need to spend a fortune to attack high-value targets.”

Dealing with one drone is hard enough but the low cost means that an enemy can now launch 100 or even 1,000 drones at a time. “It’s very difficult to deal with that oversaturation,” says Cuthell. “You can overwhelm almost any defence system.” This is a tactic that was deployed in 2024 by Iran’s air force against Israel. One of EOS’s newer systems, the Slinger, which went on sale in 2023, has seen great success in Ukraine, where 200 are currently deployed in the field, many of which were purchased by Western powers as military aid. Weighing fewer than 400kg, the Slinger can be mounted on the back of a pick-up truck and has a radar and camera system that can detect and neutralise even the smallest drone. Its demonstration video on the EOS website is captioned, “No one kills drones like EOS.”

Most of the company’s anti-drone bestsellers feature “multi-layered” responsive weaponry – meaning that operators have a selection of ways to take UAVs out of the sky. For example, a battlefield anti-drone platform like the Slinger might have a third-party missile system to take down longer-range drones; a built-in laser to “blind” drone sensors; or a chain-gun, which acts as more conventional anti-aircraft artillery. But companies such as EOS are engaged in a literal arms race when it comes to countering drones.

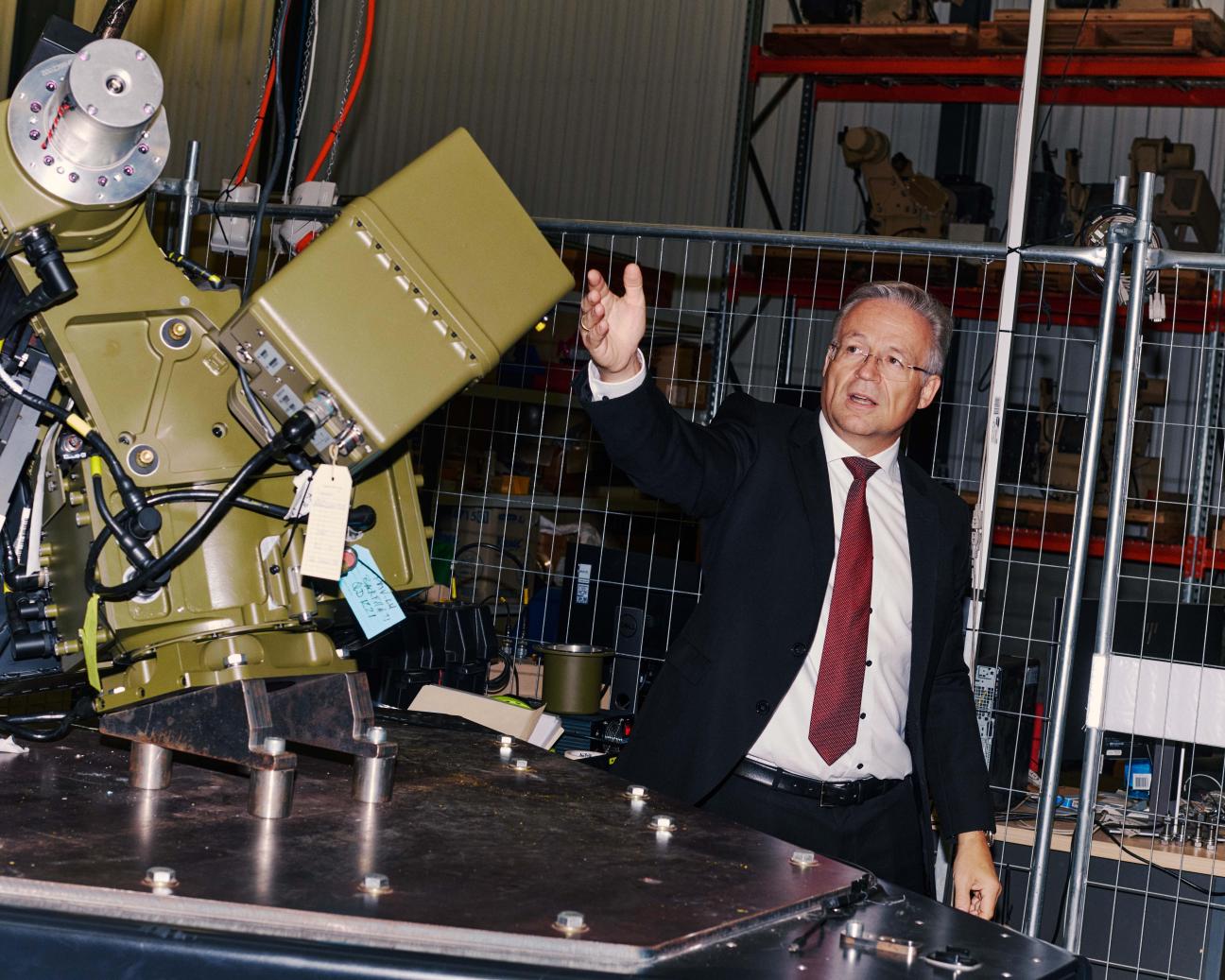

Initially, “soft-kill” mechanisms, such as jammers and spoofers, could easily neutralise UAVs but militaries have adapted them to counter such interference, meaning that “hard-kill” methods, which destroy the devices completely, have become essential. “That provides a strong tailwind for us to commercialise our innovations,” says Cuthell. As he inspects a new order bound for Kyiv, EOS vice-president of international programmes Glenn McPhee, a former Australian army officer, says that he was attracted to the company both for the “cool Australian technology” and “helping Nato soldiers defend themselves”.

EOS began life as an Australian government research institute with a focus on the space sector, including optics and laser technologies. In the 1980s the firm was incorporated as a private company and, in the early 2000s, listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. Ben Greene, one of its original founders, is a world-leading space physicist who began working in the sector not long after the first moon landing. Today he serves as EOS’s chief innovation officer. Perhaps reflecting its academic origins, EOS has always excelled at research but traditionally had less success on the business side of things. “It was a strong scientific, engineering, military and academic culture that had invented many things – but not commercialised them,” says Cuthell.

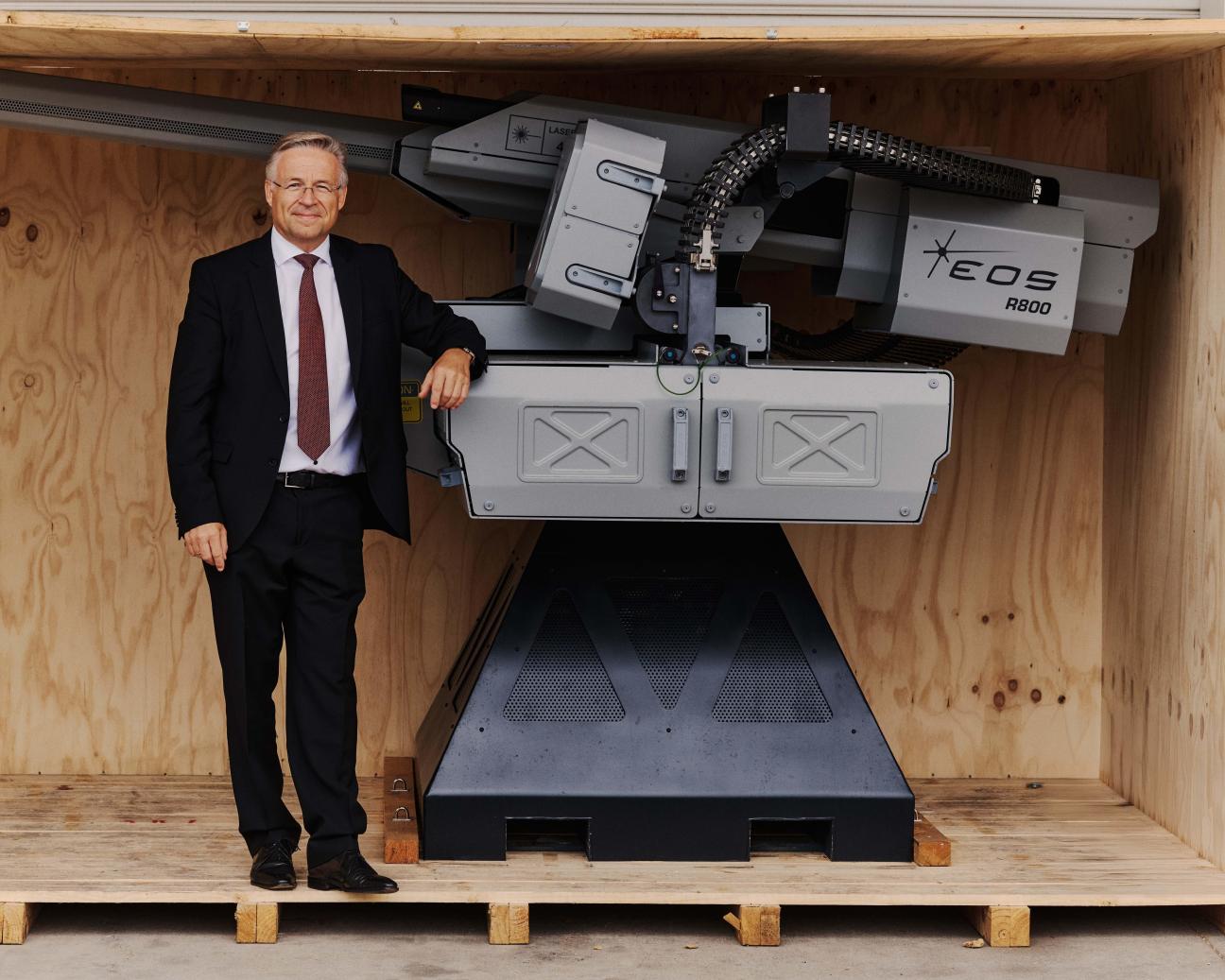

The arrival of Andreas Schwer in 2020 signalled a turning point. A bespectacled German with grey hair and a firm but understated manner, Schwer has decades of experience in the space and defence sectors, including at Airbus and Rheinmetall. In 2017 he was asked by Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman to build up his country’s defence sector by taking the helm at Saudi Arabian Military Industries, where he stayed for three years. “When I was working in Saudi, we had selected EOS as the partner for high-energy laser-weapons systems and I had done a deep due diligence,” he says. “I had found out that the company had a huge innovation and intellectual property rights portfolio but is not the best in terms of commercialising it. We wanted to take what was sitting on the shelf in terms of innovation and make real-life products.”

The arrival of new management coincided with significant geopolitical shifts – the Ukraine war, later the conflict in Gaza and rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific. All have led to a surge of interest in EOS’s products. “Investment in defence by national governments is higher than it has ever been,” says Cuthell. “Defence is an industry where technology really matters. The technological edge can often be decisive in conflict – and we’re at the cutting edge.”

Part of the leadership team’s ambition is to transform EOS into a bigger global enterprise. The firm already has four offices around the world, operates in almost 20 countries and is growing its manufacturing operations in the US and the UAE (where Schwer, who became CEO in July 2022, has a base). In 2024 it opened a laser-innovation centre in Singapore. Schwer hints that increased onshoring requirements and supply-chain concerns mean that joint ventures and localised manufacturing will play a big part in EOS’s future. “Part of the strategy is to become a truly global player,” he says. Canberra is not known as a hi-tech hub but the Australian capital has a strong university sector (EOS sponsors two research chairs) and a large defence industry, with the Australian military’s headquarters just 20 minutes down the road from EOS. The buzz of activity on the factory floor suggests that Schwer’s mission has been a success so far. Revenue to December 2023 was up almost 60 per cent year-on-year; while in the first half of 2024, it has almost doubled again. Schwer insists that the push to take products to market is not coming at the expense of ongoing research. “Research was the core,” he says of EOS’s history. “And it still is.”

EOS’s anti-drone technology has the capability to be fully autonomous, though, for now, many of its customers use human operators. The company’s systems can track and identify drones within a 5km radius, drawing on a database of almost 600 drone types constantly updated by a partner firm. The technology can identify the location and model of the drone, and whether it is friend or foe – an increasingly important function as both sides in many conflicts deploy their own UAVs. But armed forces are not the only users of this technology. Drones increasingly pose a domestic risk – whether deployed by local agitators or international terror groups. EOS systems are being sought out by organisers of major events. “That has started and will become the standard in the future,” says Schwer. He is tight-lipped about specific civilian deployments. “That’s classified.”

Space also remains a major focus. Not far from the factory, EOS shares the Mount Stromlo Observatory with the Australian National University. The firm’s laser technology can track objects in orbit down to the size of a coin, an important capability as the planet’s stratosphere becomes more cluttered with debris. “There is nobody, outside the US, that has this kind of highest accuracy tracking of objects in space,” says Schwer. “So one major application is that we track debris and provide anti-collision warnings to any kind of satellite operator. With our latest evolutions in technology, we can also move space debris, actively avoiding collisions.” Such technology also has military application. “In the long run, war will be decided in space,” he adds. Schwer pulls up a photo on his phone showing a bright-green laser beaming into the night sky. “This is not Photoshop,” he says. “This is how we use laser systems to track objects in space.” Though separate arms of the business, the anti-drone and space sectors are deeply interconnected. The success of the former builds on EOS’s decades of research in monitoring objects outside Earth’s atmosphere. “We can track any object in space,” says Schwer. “So it’s easy to downscale this sensor technology, to see further and better than anyone else on the battlefield.”

It is a long way from Canberra to Kyiv. But the cutting-edge technology being manufactured at EOS is playing an essential role as Ukraine seeks to defend itself. The conflict in the country has demonstrated in real-time how critical drones and anti-drone technology are to modern warfare – and is setting the tone for conflicts to come. Schwer was one of the first foreign business executives to travel to Kyiv after the war began. He vividly remembers his initial visit: crossing the Polish border at night, in the snow, on an arduous rail journey to meet Ukrainian officials. “Those times were challenging,” he says. “We spent many nights in the bunkers. Many meetings had to be interrupted because of missile alarms.” He laughs and says that the trip was almost derailed by difficulties securing travel insurance. “It was super expensive,” he says. But for EOS, the demonstration of commitment to supplying Ukraine with market-leading defence technology was worth every cent. “They will never forget about your engagement and commitment in the early days,” he adds. “You came to them when you were exposing yourself to significant risk.”

Schwer and his team have been back many times since – he estimates that every second month an EOS representative is in Kyiv, or often even closer to the frontlines in the east of Ukraine. “We’ve established very close contact to the leaders, to the commanders, to the officers at the frontline, to get first-hand experience and have those lessons learned introduced to our ongoing development programmes,” says Schwer. That information feeds directly into product development: EOS has simplified systems to make them more user-friendly in the field. “We are learning day by day, week by week.” The EOS boss cites the example of the Abrams tanks donated to Ukraine by the Americans. “The US has lost more than half of its donated Abrams in Ukraine by drone attacks,” Schwer says. The remaining tanks have been removed from the battlefield, awaiting an upgrade; EOS systems are being trialled for possible integration. Sometimes videos appear on social-media platform Telegram of EOS weapons protecting key Ukrainian infrastructure from Russian drone attacks. As soldiers cheer in the background, half a world away, Schwer’s team is energised. “That makes us proud.”

EOS’s other hot products

Part of EOS’s recent success has been built on the integration of its different systems – the anti-drone technology can integrate remote weapons systems, which draw on the success of laser products.

Remote weapon systems

EOS’s range of remote weapon systems combine heavy firepower with advanced surveillance capabilities. These include the R400, a lightweight model that can be mounted on trucks, tanks and ships; the mid-range R600; and the heavy-duty R800, which has a cannon and machine gun.

Lasers

In September, EOS announced it was finalising deals for its high-energy-laser weapons systems to two undisclosed international clients, in what is believed to be the first export sale worldwide of a laser weapon at that power domain. “We will be the first mover,” says Schwer. The laser weaponry can engage drones between 200m and 3km away.

Space

EOS has a range of space-related products and services, including satellite laser ranging stations, which track satellites in orbit, and space domain awareness, monitoring objects in space. One EOS brochure describes the technology as “space intelligence for battlefield commanders”.

On one Saturday in October, colles – groups consisting of people of all ages from all over Catalonia and beyond – parade down the streets of Tarragona accompanied by bands playing Catalan music. Dressed in white trousers, colourful shirts, sashes and bandannas, they make their way to the Tarraco Arena, an amphitheatre in the heart of town. Boys and girls play the gralla, a double-reed instrument, and drums called timbals. Their progress announces the 29th edition of the biggest gathering of castells, Catalonia’s human towers, which are a feat of collaboration and focus.

The human towers are the work of amateur groups that meet for rehearsals twice a week in sports halls across the region. The aim is to build towers that can reach up to 10 people high. “It’s nerve-wracking but also exciting,” says Santi Pie, leader of the Castellers de Sant Cugat, from the eponymous town just north of Barcelona. Pie’s group is one of 30 that has qualified to compete in Tarragona over the weekend in this biannual extravaganza. His job today is to co-ordinate almost 300 people as they aim to create the tallest, most intricate tower possible in order to gain a place, alongside 12 other colles, in the finals of the championship, which take place over the weekend. Monocle joins an audience of 11,000 people, a figure that doesn’t include the thousands of castellers taking part.

Over the past half-century these castells, once the result of a relatively marginal activity, have become one of the most potent symbols of Catalan identity. The tradition was declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by Unesco in 2010 and, since then, the number of colles has doubled. The pastime originated in the 18th century in the town of Valls in the Tarragona region. The colles are thought to have developed from a popular dance tradition called Ball de Valencians; music remains central to the activity. Each colla has its own band that starts playing once the base of the tower – the pinya (pine cone) – has been built, and carries on as people climb up to form the upper tiers. The song “El Toc de Castells” guides participants to co-ordinate their movements with the melody, while those at the bottom are able to estimate the tower’s progression via the music. Castells can be found at festivities across Catalonia, where the towers are often built in front of town halls and not necessarily competitive, though the activity is inherently ambitious.

As competitors slowly pile into the centre of the Tarraco Arena Plaça, a former bullfighting ring that has held castells competitions since 1932, a voice on the loudspeakers introduces each colla, many of which have names that hint at the important role played by children: the Xiquets del Serrallo (Kids of El Serrallo); Marrecs de Salt (Brats from Salt); Nens del Vendrell (Children of El Vendrell). Children as young as five or six, whose job it is to climb up to the top of the tower, wear mouthguards and helmets. In pairs, participants help each other to wrap the all-important sash tightly around their waists. This crucial part of their outfit supports the lower back and provides grip for climbers on the ascent. A banner hanging on the edge of the arena reads, “Fent pinya, fas poble.” (“When you huddle together, you make a village.”)

Surveying the crowds from the top floor of the arena is Pere Ferrando, president of the jury. He is surrounded by several screens showing all the action. All colles receive a score based on the difficulty of their constructions, and alongside six other jurors, Ferrando will be marking the performances. There are about 40 different types of castells, each of which is only complete when the enxaneta (one of the smallest castellers) reaches the top of the tower and raises one hand. Extra points are given for a safe dismantling. But today is not only about rivalry. “What makes it interesting is that you don’t necessarily need to compete with another colla,” says Ferrando. “It’s also about surpassing yourself.” That said, he will be keeping a close eye on the tug of war between the two teams angling for the tallest castells: the Castellers de Vilafranca and the Colla Vella dels Xiquets de Valls. The former has dominated the competition since the mid-1990s, winning 11 of the past 13 editions, while the latter is the team threatening this dominance.

It’s mid-afternoon, and the time has come for the Castellers de Sant Cugat to attempt their first tower – an eight-storey construction with four castellers per tier. Pie, the group leader, calls out instructions from the bottom as the stadium watches on. Every step is perfectly synchronised to complete the tower as quickly and safely as possible. As soon as the fourth storey is complete, eight-year-old Candela Casas begins her ascent, stepping on a sea of arms and heads. “I climb up by holding on to sashes, grabbing shoulders and legs,” she says when Monocle meets her backstage. She’s not scared of heights, she says, but it’s important to not look down and to stay focused. When she reaches the top and lifts up her left hand, the stadium breaks into applause. But it’s only when it’s clear that the tower will not crumble, and that everyone is safe, that the castellers begin to jump up and down, exchanging hugs and kisses. When asked what the best thing about castells is, Casas replies without hesitation, “To enjoy yourself!”

Many participants liken the experience to being part of a huge family. For Maricarmen Álvarez, who is watching nervously from her front-row seat, that is quite literally the case. She is here to support her two daughters and six grandchildren, ranging between the ages of 12 and 23. They are all taking part in the competition with the blue-shirted Xiquets del Serrallo from the Tarragona fishing neighbourhood. “It’s very hard for me to watch,” says Álvarez, pausing to point out every family member as they take their positions in the tower. “Come on, you’re almost there,” she says, cheering on as the youngest reaches the top. “Oh God, please don’t let them fall.”

Of course, not every tower can defy gravity. Though the pinya does act as a cushion and serious accidents are rare, the risk involved in castells is what makes the feat of collaboration so enthralling. Álvarez is acutely aware that this is the price to pay for the strong sense of belonging and community that castells provide. She knows that it’s the collective bravery and unconditional trust placed in others that has kept the tradition alive. “My late husband was a casteller and my great-grandchildren will probably be castellers,” she says with a sigh. “It’s passed down from generation to generation; it’s in their blood.”

Making his way through the crowd is Tarragona’s mayor, Rubén Viñuelas. When you grow up here, he says, castells are never far away. “Part of daily life is going out for a vermouth and watching castells,” he says, referencing the celebrations of Sant Magí and the Santa Tecla Festival, which take place in August and September. “Tarragona is the capital of castells, so this event means a lot to us. We pay homage to this way of life. Those of us who grew up here understand what this means and we love to see people from around the world watch on with excitement.”

As a strong expression of Catalan identity, castells often go hand in hand with a sense of regional pride that can be tied to Catalonia’s independence movement, which came to a head with an ultimately unsuccessful declaration of independence in 2017. The competition begins with everyone singing “Els Segadors”, Catalonia’s national anthem, with hands on hearts and fists in the air. Inevitably, this is followed by calls for “Independència!” Some see castells as a metaphor for the region’s strong sense of unity. “There’s the cultural aspect of making castells – it’s about looking after our language and the traditions that have been around for hundreds of years,” says Víctor Biete, president of the Castellers de Sant Cugat. Of course, that doesn’t mean that the activity is incompatible with wanting to remain in a united Spain. And while castells have grown in popularity in recent years, the push for independence has suffered some setbacks. For the first time in more than a decade, the Catalan nationalist parties failed to secure a majority of seats in the regional parliament earlier this year. The pro-union Socialist Party, of which Viñuelas is a member, now leads the Catalan government after years in opposition.

A few streets away, a parallel event is taking place in front of the town hall. In recent decades, castells have expanded beyond Catalonia’s borders. Today several international colles – from London, Paris, Berlin and Copenhagen – have gathered here before heading to the arena to support the Catalan teams. The Xiquets de Copenhagen were founded in the Danish capital in 2014, and Marta Trius, a PhD student, joined them a year ago. “When you’re abroad, the social dimension becomes even more important,” she says. “When you move abroad you have to find your family and this is like having a family.”

Back in the arena, Viñuelas says that the global appeal of castells is due to the teamwork and inclusivity involved. “It’s a piece of Catalonia that we are exporting to the rest of the world, with all its symbolism,” he says. “Everyone has a function in society – the elderly, men, women, children – just like in castells. And in the end, everything depends on the youngsters; on little boys or girls who rise high above everyone else to complete the tower.” In the end, the Castellers de Vilafranca triumphed, taking home its 13th title. For the other, there’s always next time: you’re only as good as your last castell.

How would you like your country’s leader to act if intimidated? As the US’s traditional allies consider their response to the election of Donald Trump, it’s a pertinent question.

Emmanuel Macron, the French president, claims that Europe must stop being a herbivore and become an omnivore so as to avoid consumption by the world’s carnivores. It’s no secret that most of Washington’s partners in Europe and Asia were hoping for and even anticipating a Democratic victory. I attended a media roundtable in London on the evening of 5 November featuring some of the most illustrious names in foreign affairs journalism. All of those who offered a prediction on the outcome of the vote said that Kamala Harris would win and far more time was devoted to discussing her potential appointees than Trump’s. Thankfully, no one will suffer as a result of that faulty guesswork – but the same cannot be said for any diplomats or government officials who are inadequately prepared.

Had they sought advice in the aftermath of the shock result, they would have found no shortage of purveyors. Much of what most commentators say boils down to an insistence that leaders should indulge the new president’s allegedly transactional nature and narcissistic tendencies – that he must be flattered and bribed into doing the right thing. But this betrays the same cynicism that has led to the election of politicians such as Trump, who have exploited voters’ antipathy towards the institutions of government and their leaders, who he has labelled as dishonest and corrupt. What is more dishonest and corrupt than kowtowing to someone who you believe to be wrong?

Of course, we don’t know how Trump will treat the likes of France when he begins work on 20 January. Portentous warnings of a vengeful isolationist could well be overblown. But if the president does use intimidation and threats to force Washington’s erstwhile friends to do his bidding, those same friends should not be cowed. Foreign relations, especially those conducted by the world’s economic and military hegemon, have always been transactional. Even the Marshall Plan, often presented as proof of the US’s inherent nobility, had cynical motives – namely, curbing the influence of the Soviet Union in Western Europe.

Moreover, though the US has often claimed to be acting selflessly, while invoking its self-declared exceptionalism, no country is exceptional when it comes to how it should treat others. One need only look at the number of nationalist strongmen currently in power across the globe to understand that America’s situation in 2025 is far from sui generis. Each of these leaders has preached their country’s innate superiority in order to win elections. And while it’s true that none of them are running as powerful a nation as the US, neither are they bound by the checks and balances of that country’s constitution.

What should the US’s allies do if they are faced with a combative Trump? What they think is right, of course. This might sound idealistic but it will protect their countries (and careers) in the long term. Much of the present crisis in liberal democracy stems from the fact that voters are so enraged by their leaders’ prevarication on certain issues that they are drawn to those who they believe are at least genuine. It is in the darkness between the official explanation and the concealed truth that populism festers and metastasises. Trump is not the first US president whose election has confounded the country’s allies; nor will he be the last. He will only be in the job for another four years but the damage done to voters’ faith in politicians who find themselves lying to placate him will take far longer to repair. Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that.

One of the things that distinguishes soft power from hard power is that the former is a two-way relationship. The point of hard power – tanks, fighter jets, the proverbial sending of the marines – is that you don’t ask the permission of whoever you’re menacing. Soft power works best when the party on the receiving end is a willing participant. In October the annual Brics summit was held in Kazan, Russia. It was portrayed by Russia as a defiant diplomatic triumph for Vladimir Putin. Putin is, in theory, a pariah: an imperialist warlord wanted for war crimes. But 24 world leaders – far beyond the official membership of Brics – attended.

But it is striking how few of the participating countries regard Russia as a trustworthy ally and how strapped for actual friends many of them are. It was, to a large extent, a gathering of the “soft power-less”. These countries might be rich, fearsome or undeniably (if infuriatingly) important but they command little affection. Russia, to cite an obvious example, has serially squandered its formidable soft-power arsenal – glorious literature, fabulous music, scientific prowess – on demented ideological projects, often involving the coercion of reluctant neighbours. Moscow now has clients and customers, flunkies and cronies, hostages and victims but few, if any, friends.

Western policymakers have recently been fretting about the posse that Russia is assembling to challenge Western hegemony. Often characterised as the Axis of Upheaval, it is generally held to include Russia, Iran, North Korea and China: four countries united by little beyond the fact that they dislike and suspect the West more than they dislike and suspect each other. The regimes of all four rule by fear. Many of their people would leave in a heartbeat.

All of the Axis of Upheaval might well dismiss soft power as an effete and decadent notion, scoffing that there is a clue in the adjective “soft”. It was a predecessor of Putin’s who is reported to have snorted, when warned of the (considerable) soft-power influence of the Vatican, “How many divisions has the Pope?” But presenting an unrelentingly combative visage to the world will only get you so far. Hard power is a willingness to fight – and any idiot can do that. Soft power is having something worth fighting for.

Andrew Mueller hosts ‘The Foreign Desk’ on Monocle Radio.

More than 2,000 years ago, the Romans transformed the settlement of Hispalis, now Seville, into a centre of shipbuilding and trade. Some 90km from the Atlantic, the inland river port was ideally placed. Today, five centuries since the colonisation of the Americas brought Andalusia to its apex as a seafaring hub, the Guadalquivir river continues to carry ships laden with olive oil and wheat products.

But walk along the river’s banks, as holidaymakers are ferried gently to and fro, and you’ll see that the languidly flowing waters no longer shift fortunes as dramatically as they once did. Instead, Seville is now shaking up the world thanks to the aviators who first took to its skies more than a century ago.

With two major manufacturing sites in the city that trace their roots to those pioneering days of aviation, Airbus has proven itself to be a powerful driver of industrial innovation in Andalusia and beyond. In 2019 the company accounted for 60 per cent of Spain’s aerospace and defence exports at a value of €4.3bn. Airbus Spain reported a revenue of €6.08bn in 2023, with its Defence and Space division pulling in 66 per cent of that total. In Andalusia, aircraft and spacecraft exports grew by 61 per cent year on year in the first three quarters of 2024 to reach €1.78bn. Meanwhile, the overall Spanish aerospace industry grew by 24 per cent between 2012 and 2022 and saw significant investments in R&D, accounting for 10 per cent of the industry’s sales.

Monocle is driving past neat rows of olive trees along the perimeter of Seville’s San Pablo Airport when the vast hangars of Airbus’s installations come into view. Airbus employs about 3,400 people at its facilities in Cádiz and Seville. In addition to the final assembly lines of the C295 and A400M military transport aircraft at San Pablo, there’s an internationally accredited flight-training centre that receives 2,800 students a year, including pilots, mission crew and mechanics from 90 countries across the globe.

Senior manager Arturo Lammers leads us to the cavernous final assembly line of the four-engine A400M that’s inside a four-storey hangar. “I remember we had visitors from the Bundestag at the start of the A400M programme,” says Lammers, who worked on the twin turboprop C295 for 24 years before taking over the newer plane’s final assembly line. “One of the German representatives asked me, ‘How come the A400M is assembled in Seville?’ And I answered quite naturally, ‘Because we are the best in Europe at building planes for military transport.’” Lammers knows the aircraft intimately and has even parachuted out of one or two.

Airbus Spain was born of the merger in 1971 between two homegrown enterprises, Construcciones Aeronáuticas SA (CASA) and Hispano Aviación. In 1926, CASA, based in the Madrid region, established its first outpost in Cádiz, where it built military seaplanes under a German licence. Barcelona-based Hispano-Suiza, an automaker that produced almost 33,000 aircraft engines for use during the First World War, went on to set up Hispano Aviación in Seville in 1943. CASA’s merger with Hispano Aviación in 1971 consolidated more than 50 years’ worth of the region’s experience in engineering and aviation, standing Spain in good stead when it joined the Airbus project later that year.

We follow Lammers up three flights of stairs to a vantage point from which we can marvel at the 42.4-metre-long carbon-fibre wings below us that are being lowered delicately onto the awaiting fuselage. Their descent is aided by laser guidance as part of Airbus’s “best-fit” technology, which matches the live-assembly process to theoretical computer models in real time.

“Today is one of the drumbeat moments for everyone across the entire planet that is working on the A400M,” says Lammers. The A400M aircraft is an example of international collaboration, from its design phase to the various countries that build its major parts – such as France, where the cockpit is produced; the UK, where the wings are made; and Germany, where the fuselage comes from. Next door, the five stations of the C295’s final assembly line are more of an Andalusian affair. Some 75 per cent of the Spanish-designed plane’s major sections are integrated in the region; in addition, services such as painting, delivery, maintenance and client support are supplied locally. “We Andalusians are generally nonconformists,” says Luis Marmolejo Vidal, the head of Airbus Spain’s light transport aircraft, flight line and delivery centre. “We like to feel proud of what we do. I believe that this is why there has been such a strong push to create a state-of-the-art industry within the region.”

Over the past decade, the facility has fully digitised its production processes. Workers rely on tablet computers to view schematics and troubleshoot, as well as to track progress between shifts and across stations. A recent innovation – augmented-reality goggles with integrated voice activation – ensures that workers can access computer data hands-free. When we test the specs, we are transported to the interior of a fuselage, where wiring and its related fixtures are highlighted in canary yellow to guide correct placement.

According to María Ángeles Martí, the senior vice-president of Airbus Defence and Space, the Andalusian facilities will continue to hold great importance to Airbus, particularly as the EU progresses towards its strategic defence goal of increasing technological autonomy as a response to growing instability in the region due to Russian aggression in Ukraine. “Airbus Defence is part of the road map for European defence,” says Martí, before outlining the division’s work on the EU’s Future Combat Air System and Eurodrone projects. The company’s Tablada facility in Seville will assemble the Eurodrone’s central and rear fuselages, as well as other parts.

While it is undeniable that, as Spain’s largest aerospace manufacturer, Airbus exerts a powerful influence, more than half of Andalusia’s 147 aerospace companies have fewer than 50 employees. Juan Román, the managing director of business cluster Andalucía Aerospace, says that there is an ongoing debate within the sector about whether the region’s enterprises should join together to form larger entities in an effort to better compete in the global marketplace. “On the one hand, we might consider increased size to be a key factor in improving robustness,” he says. “On the other hand, we realise that the flexibility and specialisation that a small company brings is far greater than that of a larger company.”

One of the cluster’s members, Solar mems Technologies, fits that bill. Not only is the firm highly specialised – it produces sun sensors built with micro-electromechanical systems – but it is also dedicated exclusively to the space sector, which currently accounts for a mere 3 per cent of the companies in the Andalusian aerospace industry. The Spanish Space Agency’s move from Madrid to Seville in 2023 portends a significant change in the subsector.

José Manuel Quero Reboul, a co-founder of Solar mems and tenured professor at the University of Seville’s Higher Technical School of Engineering, explains that the company’s business model is rooted in experimentation. At the university’s lab, he develops technology side by side with students that is then patented. He hands over these experimental innovations to the company so that it can translate them into marketable products, with 1 per cent of any sales going back to the university. “Though I’m sort of the father of all this, I try not to meddle,” he says with a smile. “I’m a researcher.”

The turning point for Solar mems came with a collaboration with Airbus Defence and Space as part of a project to build 648 telecommunications satellites for the Oneweb network, the only alternative constellation to SpaceX’s consumer-orientated Starlink. “Until that point, we were doing things by hand and maybe could build four devices a month – and then suddenly we needed to produce two a day,” says Quero Reboul about the order of 1,000 optical sensors that the company had to fulfil out of its tiny lab.

An Airbus team took up residence in the Solar mems clean room to teach its technicians how to replicate quality at scale. “We are one of the few companies in the sector that have implemented assembly-line production,” he says. That allowed Airbus to make two satellites a day in its Cape Canaveral facility. Low-orbit satellites, such as the ones that Oneweb makes, can cost less than 10 per cent of what is required to build traditional ones.

While Seville’s legacy in industrial machining keeps it at the centre of the Andalusian aerospace industry, other southern cities are expanding into alternative areas. Coastal Malaga is an incubator for specialists in digital systems such as avionics software, while Huelva, near the Portuguese border, has the potential to become a hub for drone development. In October 2024 a 75-hectare installation for the testing of unmanned aerial systems opened there, becoming Europe’s first airfield dedicated to the development and trial of drones weighing up to 15 tonnes.

Aníbal Ollero is Andalusia’s foremost expert in unmanned aerial systems, as evidenced by the more than 650 publications that he has authored on the subject. He believes that diversifying the aerospace sector beyond traditional manufacturing will help to ensure its long-term success. “We mustn’t only stick to what we already know,” he says. “We should look for what else might one day play an important role in aeronautics.”

Monocle meets Ollero at Seville’s GRVC Lab, where he leads a group of professors, researchers and engineers in developing aerial robots. The indoor testing arena brings to mind an aviary: the high-ceilinged space is draped with a tent of white rope nets. This is meant to offer protection to the team’s “birds” – ornithopters, robots with flapping wings – that flutter through the air in a hi-tech homage to nature. These lightweight ornithopters are capable of quiet, hazard-free flight, particularly in comparison to rotary-wing drones, making them ideal for use in proximity to wildlife. The GRVC Lab is working on a project in which its ornithopters will be used to inspect and maintain power lines in one of the region’s major nature reserves, thus reducing the possibility of disturbing migratory birds, as well as the vulnerable Iberian lynx.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Ollero is busy with various projects that aim to keep Seville at the cutting edge of drone technology. He is the manager of the soon-to- open Center for Innovation in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Urban Air Mobility, which will consider ideas such as the aerial delivery of packages and transport via air taxis. He will also continue as the scientific director of catec, a research and development centre for aerospace technology that links the public and private sectors.

Ollero says that his work demands a certain steadfastness. “Researchers must somehow see the future,” he says. “The research that we began 20 years ago is bearing fruit now. It’s possible that we won’t get to see the results of what we are working on today.”

Innovators at Australian-Spanish start-up Dovetail Electric Aviation, however, are working to bring the future as close to today as possible. Last summer the company went to Seville to present a prototype of its hydrogen- fuel-cell powered electric motor, which can be retrofitted on existing aircraft in the under-20-passenger category. While hydrogen-fuel-cell technology is not yet advanced enough for use in long-haul flights, Dovetail has set its sights on shorter flights as an achievable goal within the next two years. A maiden flight of its electric-powered engines is planned to take place in 2025.

“In addition to being zero-emission, electrification’s promise lies in its ability to significantly reduce operating costs,” says David Doral, the company’s co-founder and ceo. Electric-battery powered engines can achieve flight times of 15 to 20 minutes, which are suitable for skydiving centres and other uses in tourism, such as island-hopping or scenic flights. With the addition of hydrogen fuel cells, an engine’s range extends to one hour, opening up the possibility of a renaissance in regional air travel between cities that are currently unviable to connect by air.

Though Doral has had an international career in the aerospace sector, working for companies including Embraer in Brazil and Boeing in the US, the time that he spent in Seville left an impression. “I’ve always seen it as a fascinating place for growing projects,” he says, before outlining Dovetail’s plans to expand in Spain with an R&D base and manufacturing facility. Though it’s not clear whether Andalusia will be Dovetail’s future home, Doral mentions that the impending arrival in Seville of Swiss aircraft manufacturer Pilatus bodes well, as the company’s PC-12 is “perfectly compatible” with Dovetail’s retrofits.

Andalusia’s aerospace industry presents fascinating contrasts, with tradition and innovation combining to sparkling effect. For major players with staying power and forward-thinking spirits alike, it seems that there are nothing but clear skies ahead.

For the global photography market, 2023 was a record year in terms of sales volume. But there was a catch: the total value of those sales was $62.4m (€57.4m), marking a fall from 2022. Though the market is active, the sector’s buyers don’t necessarily have the deepest pockets. For many, photography offers an entry point to art collecting.

In a world where we can take and view images with a tap of a finger on a smartphone, what does it say about the medium that we continue to collect and surround ourselves with photographs? What makes the snapshots that we choose for our walls special and how are they valued? And how does living with photographs change the way we experience a room?

Over the following pages we explore the art of building a collection. We visit a Park Avenue auction, spotlight galleries across the globe and explore the history of the art form. We also enter the homes of some keen-eyed enthusiasts to take a peek at their extraordinary collections. They might inspire you to snap up a print or two of your own.

At Monocle, we take the pursuit of a fantastic shot seriously. And sometimes, a good photo shouldn’t be confined to the page. —

AUCTIONS to watch

Negative equity

New York

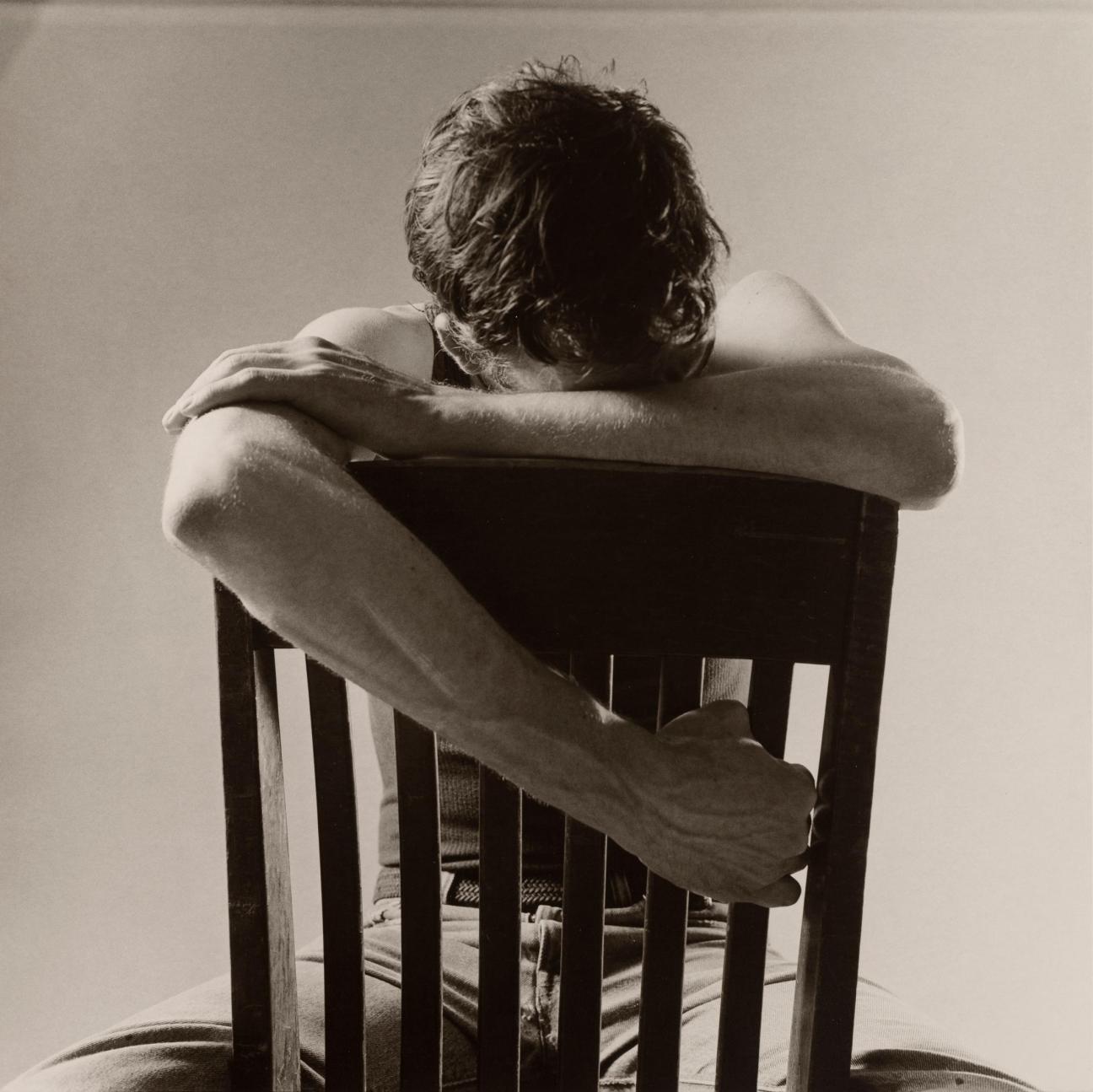

Within seconds, Peter Hujar’s lifetime print, titled “David Wojnarowicz (Village Voice ‘Heartsick: Fear and Loving in the Gay Community’)”, climbs in price from $26,000 (€24,000) to $70,000 (€64,700), before continuing upwards. The photograph takes just two minutes to be sold at a final price of $139,700 (€129,300). “It’s the only lifetime print of that image that we’ve seen,” says Sarah Krueger, Phillips’ head of photographs in New York, who is the auctioneer when monocle attends the Park Avenue event. (A “lifetime print” is one that’s produced while the photographer is still alive.)

Until the Hujar print, the mood in the auction room has been relatively calm, with a small group of seated bidders and others dropping by for certain lots. Every now and then, someone will gently raise their paddle. One man in the second row bids by lifting his finger with the slightest of movements. Blink and you’d miss it. “He’s a collector who I’ve been dealing with for decades,” says Christopher Mahoney, senior international specialist, photographs, at Phillips. “I remember seeing him in the 1990s. He’s a real auction pro.”

That was back when the sale rooms were full and frantic, sometimes brimming with more than 100 people. Nowadays, though the auction is still held in a physical space, most of the action takes place by phone or through the online platform, which people log into from around the world. “The technology has become so good and accessibility has expanded so much,” says Mahoney.

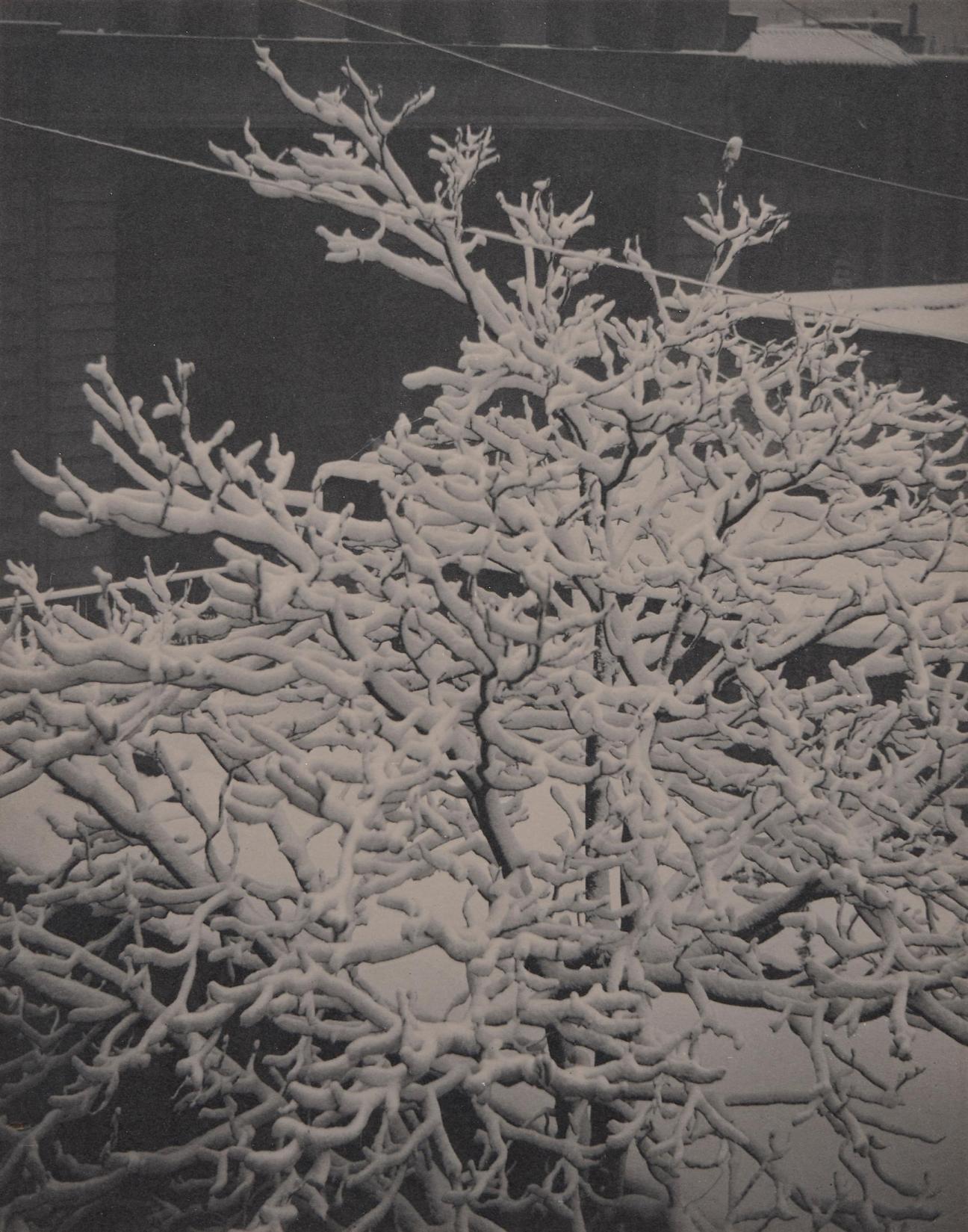

Whether attending in person or engaging down the line, thousands of bidders from more than 40 countries have turned out for the slew of famous photos under the hammer, including Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Paper Drop Novo”, Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Still #18” and Alfred Stieglitz’s “From the Back Window – 291 – Snow Covered Tree, Back-Yard”, which sells for $304,800 (€282,330).

The price that a photograph achieves at auction is the result of several factors: the condition and size of the print, how many were made, how often one becomes available and how long after the negative date the work was printed. “While there are innumerable variables for our valuations, rarity and condition can be the biggest drivers,” says Krueger. Though the most common prints that she sees at auction are gelatin silver, chromogenic and pigment, many contemporary artists use traditional processes such as the 19th-century daguerreotypes.

How quickly something sells depends, of course, on how decisive the bidders are. “It’s from 40 seconds to a minute when people have to make decisions,” says Krueger.

Long-time collector Louis Berrick, who loves the work of William Klein, recommends going in with a plan and a sum in mind. He is less concerned with rarity and appreciates how accessible the art form can be. “If there are 40 photographs that were made and signed by the artist, that’s great,” he says. “It’s a very democratic art form.”

Like most collectors, he’ll peruse the catalogue beforehand and take note of a few pieces. But he mostly chooses what to bid on through impulse. “I decide in the moment,” says Berrick. He’s glad that the online platform allows more bidders to take part but says there’s nothing like being in the room. Before the auction, Berrick will view the collection in person, sometimes asking if he can see the photographs outside the frame. “You’ll go there and realise a photograph isn’t so big. Or you’ll see something different in the picture. It changes your experience.” Mahoney also encourages collectors to engage with the collections if they can.

In the auction room itself, there’s one piece of advice that everyone will tell you: unless you’re bidding, keep your hands firmly in your lap. Lifting a finger can come at a high price.

The top-selling prints at Phillips’ New York photography auction on 9 October 2024

Peter Hujar

David Wojnarowicz (Village Voice “Heartsick: Fear and Loving in the Gay Community”), 1983.

Gelatin silver print.

10⅛ inches 3 10 inches (25.7cm 3 25.4cm).

Printed by the artist, with the estate’s copyright-credit reproduction limitation stamps. Signed, titled and dated by Stephen Koch, executor of the Hujar estate, in pencil.

estimate: Up to $50,000 (€46,250).

sold for: $139,700 (€129,300)

Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Still #18, 1978.

Gelatin silver print.

7⅝ inches 3 9½ inches (19.4cm 3 24.1cm).

Signed, dated and numbered 5/10 in pencil on the verso.

estimate: $80,000 (€74,100) to $120,000 (€111,150).

sold for: $101,600 (€94,110)

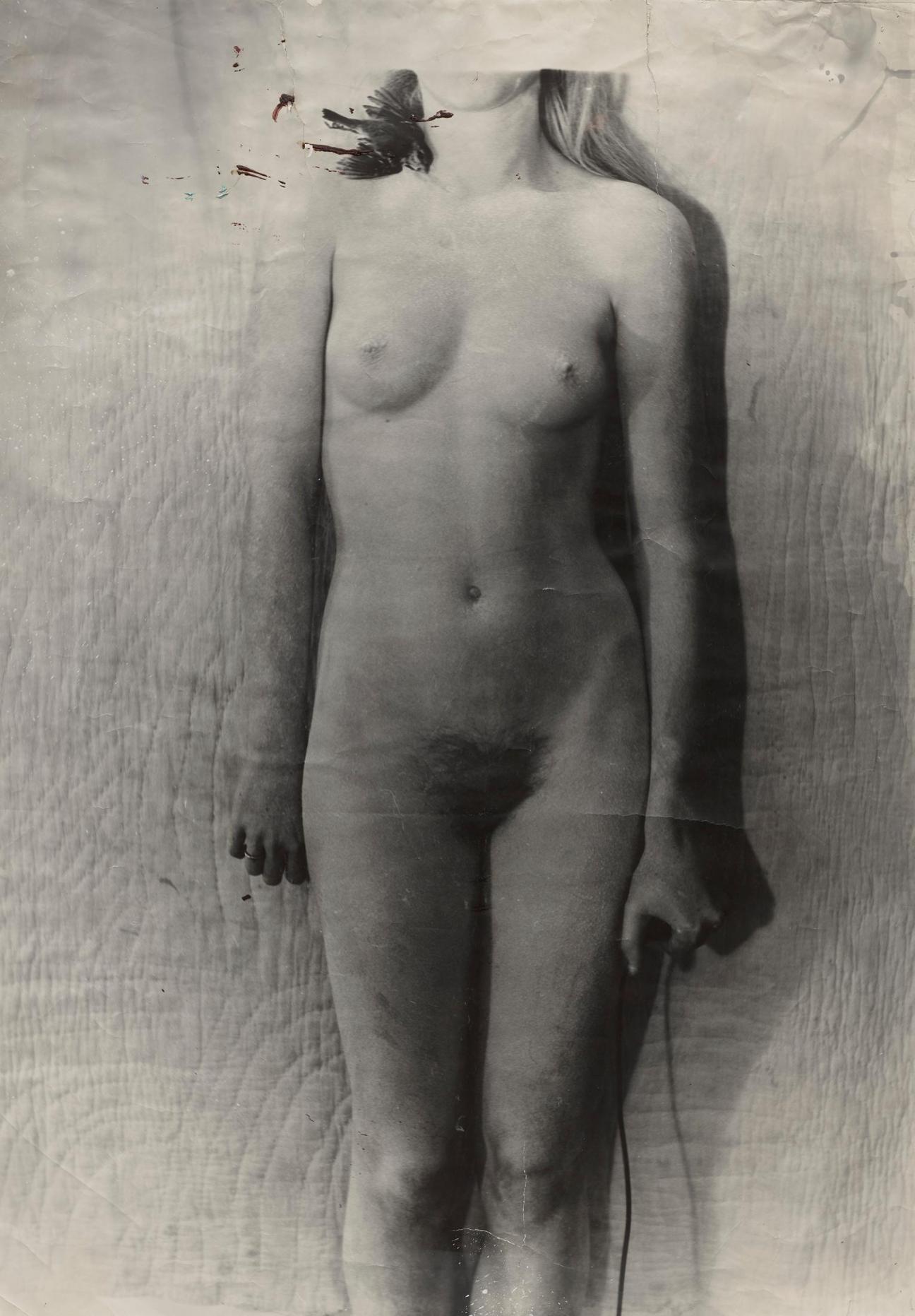

Francesca Woodman

Self Portrait (with Bird), 1976-78.

Unique oversized gelatin silver print with applied paint and pigment.

49¾ inches 3 35½ inches (126.4cm 3 90.2cm).

with frame: 58⅜ inches 3 43⅛ inches (148.3cm 3 109.5cm).

estimate: $150,000 (€139,000) to $250,000 (€231,570).

sold for: $190,500 (€176,450)

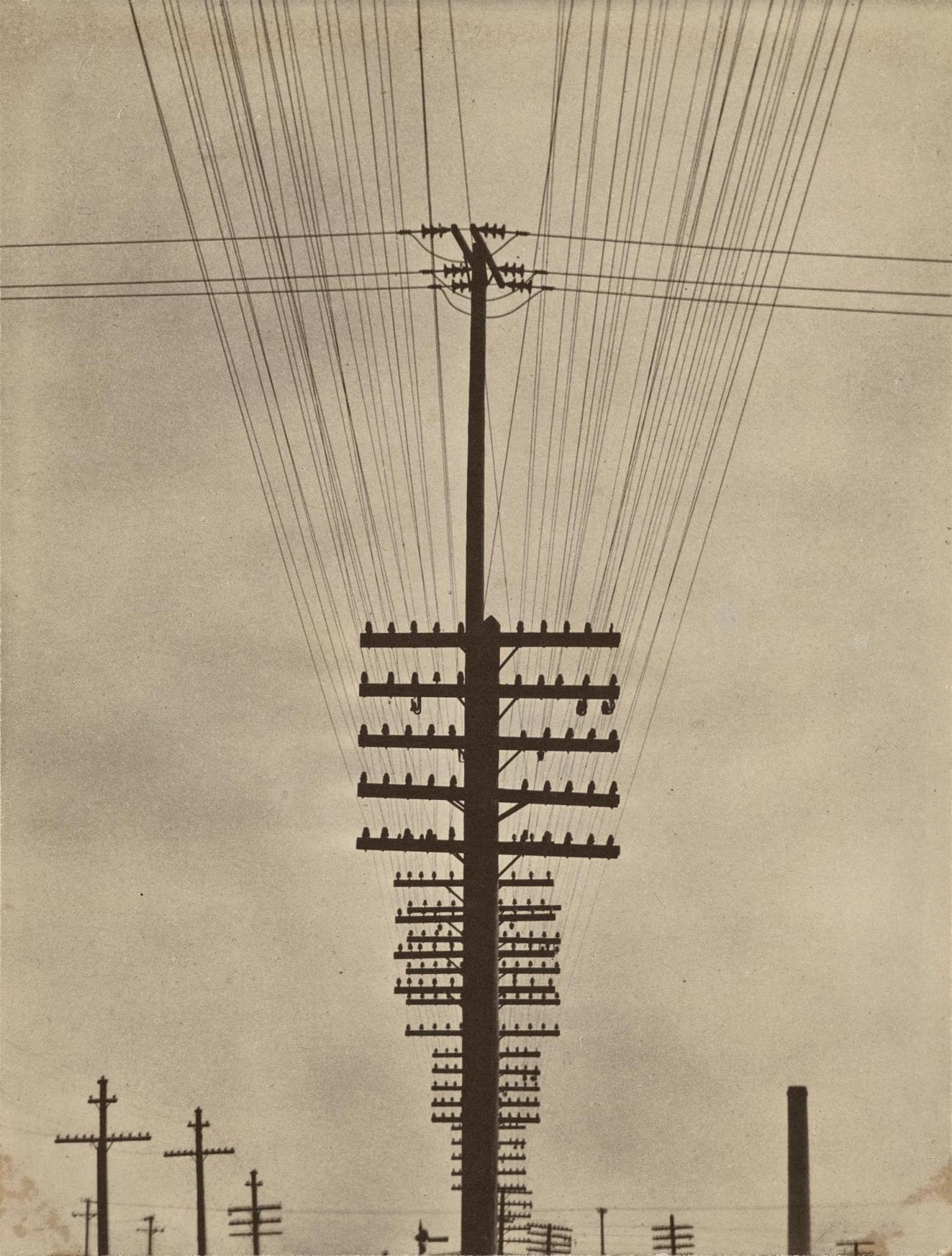

Tina Modotti

Telegraph Wires, circa 1925.

Platinum print.

9⅜ inches 3 7⅛ inches (23.8cm 3 18.1cm).

Former owner Vittorio Vidali’s “Commissar of the Fifth Regiment” stamp, a typed caption label and reduction notations in an unidentified hand in pencil on the verso.

estimate: $150,000 (€139,000) to $250,000 (€231,570).

sold for: $177,800 (€164,840)

Alfred Stieglitz

From the Back Window – 291 – Snow Covered Tree, Back-Yard, 1915.

Platinum print.

95/8 inches 3 75/8 inches (24.4cm 3 19.4cm).

estimate: $250,000 (€231,570) to $350,000 (€324,190).

sold for: $304,800 (€282,330)

Into the academy

Though photography has been recognised as an art form by connoisseurs since the late 19th century, the medium took a little longer to gain wider recognition. Here, we trace its journey into the highest echelons of the art world.

1940

Beaumont Newhall becomes the first photography curator of Moma in New York and starts acquiring works and curating pivotal exhibitions.

1971

The Photographers Gallery opens in London as the first UK public institution to exhibit the medium.

1972

Sotheby’s London is the first international auction house to hold a regular standalone photographs auction. Its New York outpost followed suit in 1975.

1978

Richard Avedon becomes the first living photographer to have a retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, legitimising fashion photography as a genre.

1980

The Association of International Photography Art Dealers holds its first annual fair in New York.

1981

Howard Greenberg opens his New York gallery exhibiting and selling primarily photojournalism and street photography, which have become pillars of the market.

1990s

The number of photography galleries and dealers in North America and Europe grows. The focus in the markets is New York, Paris and London.

1997

Paris Photo – now the world’s largest and most esteemed international photography fair – is held for the first time.

2008

Christie’s holds the first single-owner auction of photographs from the Leon Constantiner Collection, bringing in more than $7m (€6.5m).

2009

The Tate in London appoints its first photography curator, Simon Baker, who forms the museum’s first Photography Acquisition Committee.

2011

At Christie’s New York, Gursky’s “Rhine II” sets a record as the most expensive photo ever sold, at $4.3m (€4m).

2019

The Rencontres d’Arles photography festival hosts its 50th birthday. Attendees include Swiss arts patron Maja Hoffman, whose Luma Foundation is completed with the Frank Gehry tower in Arles in 2021.

2022

Man Ray’s “Le Violon d’Ingres” smashes its pre-sale auction estimate of up to $7m (€6.5m), becoming the most expensive photograph ever sold at $12.4m (€11.5m).

2024

London’s v&a hosts Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection, collected over 30 years.

May 2025

Photo London will celebrate its 10th anniversary, cementing the city’s place as a centre for photography collecting and expertise.

At the southernmost tip of Mumbai, people congregate along the shoreline, seeking respite from the tropical morning heat. This is Colaba, a former island that’s now one of four peninsulas dangling from India’s most populous megacity into the Arabian Sea. Once a haven for jackals and pirates, Colaba became a mercantile enclave that blossomed into a jewel of the British Raj in the late 19th century after colonial authorities reclaimed land in the strait separating it from the rest of what was then, and still is (for many locals at least), known as Bombay. Today, though it is integrated within the city, at least physically, its architectural splendour, old-world charm and artistic sensibility mean that it sits apart from the bustle and chaos of the wider metropolis. The light here is meek, milky – it whispers through the haze. Monsoon season has passed and Diwali is just round the corner.

Colaba Causeway, the area’s main drag, has an eclectic inventory of shops, from hole-in-the-wall purveyors of bric-a-brac, where tables are piled high with silver goblets, vintage glasses and Kolhapuri sandals, to nearby high-end boutiques such as Amit Aggarwal’s flagship and international multi-brand boutique Le Mill. There are minimalist cafés and sleek wine bars reminiscent of Copenhagen or Melbourne, as well as old video shops and impossibly pokey office buildings where ceiling fans beat lazily day and night.

Running off the causeway are knots of lanes, where many homes have grand Victorian façades. Pratik Perane, a city architect, points to the middle floors of the buildings as we pass by. Many used to house just one colonial administrator but following the fall of the British Empire they were bequeathed to favoured Indian families. Palm trees droop over the red Mangalore-tiled roofs typical of the area. “All the history of the place is still here,” says Perane. On the other side of the jagged spit from where we stand, meandering Marine Drive is studded with colourful art deco buildings; Mumbai has the second-largest concentration of the architectural style of any city except Miami – and many of them are found here in Colaba. Some incorporate winking allusions to the area’s seafaring history, with deck-style balconies or nautical colourways.

In photographs, Colaba looks like a time capsule. On paper, it’s more often described as the heart of Mumbai’s burgeoning art scene. In the 1990s and early 2000s, gallerists began occupying its high-ceilinged buildings and lofty spaces. There are about 30 galleries here now – contemporary, local, traditional and international – most tucked up winding staircases on the second and third floors of old buildings that have camera shops, tailors or accountants below. One of Colaba’s most famous is Jhaveri Contemporary, housed in the historic Devidas Mansion.

The view from the gallery’s wide windows is spectacular, framing the Gateway of India, Colaba’s most famous landmark, at a perfect golden ratio. In its 14 years, Jhaveri Contemporary has focused on South Asian artists from the diaspora, representing well-known figures including Simryn Gill and Lubna Chowdhary. It was a natural alignment to set up a base in Colaba. “The entire gallery world is here,” says Priya Jhaveri, one half of the sister duo that run the gallery. Her sibling, Amrita, who is now based in London, came to Mumbai in the early 1990s to set up the first Christie’s office in India.

It wasn’t a glamorous time for Colaba, which had become a haven for Westerners looking to buy heroin or marijuana. The enclave’s crumbling doorways were filled with slumped, stoned tourists. But by the time the sisters were ready to open their own gallery, a smattering of others had already set up. “It was the only place, really, if you wanted to be in art,” says Amrita. More gallerists are flocking here: contemporary gallery Nature Morte opened up less than a year ago and Kolkata-based Experimenter Gallery, which focuses on multidisciplinary works, just before that. There’s a real community and intermingling between the artists and the galleries, says Amrita. “We’re all each other’s clients and friends and buyers.”

If you head to the edge of Colaba in the morning, following the smell of salt and fish, you get some sense (or, perhaps, scents) of its past life. The area’s name derives from the Koli fishing communities who first inhabited its shorefront. At dawn, clusters of women wait by the water to meet the fishing boats that bob over the horizon. They are en route to Sassoon Docks, which are named after the Baghdadi Jewish family that built a business empire here in the 19th century. Today these docks house one of the country’s largest fish markets, which moves between more than 20 tonnes of fish per day. Mumbai accounts for about 30 per cent of India’s total seafood exports and Sassoon Docks makes up a key portion of that tally. Here, the women, saris knotted at their hips, are the drivers of the action, shouting and bargaining and hawking their husbands’ hauls of pomfret, prawns and bombil.

The Sassoons are responsible for a great number of the grand old buildings in Colaba but the area is more closely associated with another homegrown dynasty: the Tatas. Almost everyone monocle speaks to mentions the Parsi clan whose Tata Group conglomeration is India’s most valuable company (worth about €375bn). Ratan Tata, the group’s famous ex-chairman, died in October. It was his ancestor, Jamshedji Tata, who first saw the appeal of Colaba’s quietude, building a series of mansions here in the late 19th century. Today their crumbling façades and Victorian names stand as testament to the area’s colonial past: the Radio Club, Yacht Club and Sandhurst House, to name a few. A little further along, at the waterfront’s edge, sits the strip’s grande dame, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, a five-star, 285-key behemoth with a foyer that has been graced by names such as John Lennon and Hillary Clinton, and on whose steps the last viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten, proclaimed the country’s independence at the stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947. That historic balcony overlooks the Gateway of India, built to commemorate the visit of King George V in 1911 and through which the last British troops left the country in 1948.

Though the Tatas, and the British, have since moved on, Colaba is still home to many Parsis, a Zoroastrian community descended from Persian refugees who came to India in the seventh century. The yellow archway of Cusrow Baug, a 1,540-apartment residential compound restricted to Parsis, is another landmark. As we stand in its centre, looking up at the brutalist-style blocks, we meet two of the compound’s oldest residents, Ruby Lilowalia and her husband, Feroz, who are out on their evening stroll. Ruby’s grandmother moved to Cusrow Baug in 1935; her grandson will be the fifth generation of their family to live here. What began as free housing given to people who couldn’t afford their own has now become a redoubt for all strata of the Parsi community. Its residents began to prosper and grow wealthy but, she says, they still wanted to live here. “It’s wonderful for children – and old people,” she says, laughing. “We have everything here: a gym, a physiotherapy centre, even a school. There are many more Mercedes than when we were growing up but we’re together. It’s safe. That’s why people want to stay.”

When India was finding its feet as an independent nation, the new owners of Colaba’s mansions struggled to pay for their upkeep and many buildings fell into disrepair. Now, strict regulations by local authorities and Unesco mean that they can’t be knocked down, nor repurposed. So they remain frozen in aspic as the hyperactive city around them changes rapidly. “People come here for the memory of Bombay, what it was,” says Perane, the architect.

Inside Bakhtavar, a whitewashed art deco palazzo on the shorefront, Monocle takes the stairs up to the home of Ravi Jain, a former drinks company executive, who has lived in Colaba for the past 30 years. The calm of his wood-panelled apartment is a world away from the hubbub of the street below. “Once you live here, it’s hard to get out,” says Jain. “It’s greener, older, more charming.” He can only recall one of the houses in his block being sold since he moved in; everything else has moved within families. Jain’s sons will live in this building when he’s gone.

“This little pocket of south Bombay has its own charm,” says Meeta Singh, an estate agent who has worked in the area for more than 10 years. “But it’s not expensive, not like people might think. There are parts of Mumbai with New York prices, Hong Kong prices. But Colaba is reasonable.” A one-bedroom apartment, says Singh, would cost just less than €300,000. Renting is a lot cheaper, especially if the house falls under the old pagdi system, in which tenants pay a token amount in order to be deemed co-owners and share responsibility for the property’s upkeep. This area is not the first choice for India’s burgeoning high earners in tech and finance – Singh puts this down to the fact that these people generally prefer new buildings with pools, guards and gyms rather than the quaint but high- maintenance residences found in Colaba. There are almost no high-rises here; the mod cons are serviceable rather than state of the art. “Colaba is for people who want something special, with a sense of its own character,” she says.

That character is exactly what drew designer Divya Thakur to the area 20 years ago. Her apartment, which she redesigned herself, houses a museum of curios collected from around India as well as from antiques markets in Europe. A Florentine chandelier hangs in the bathroom while a bronze bull from nearby Chor Bazaar anchors the living room. Her walls are painted in moody washes of blue, lime and dusty pink.

For Thakur, Colaba is its own ecosystem. She puts much of the renewed interest in the area down to city planning: the Eastern Freeway, which connects northern Colaba to downtown Mumbai, has cut the journey time between the two from about two hours to 30 minutes. “Now if you want to pop in to see an art exhibition, it’s not a big deal,” she says. “Galleries bring the people, who bring the vibe, which brings even more culture. It’s like a cycle.” Here, a Bombayite can catch a couple of art exhibitions, stop for a canteen lunch, pick up a dress from local designer Lovebirds Studio and refuel on Subko coffee without ever getting behind the wheel of a car (humidity levels permitting). “It’s walkable, it’s easy – and that makes all the difference,” she says. But there have been periods, says Thakur, when Colaba lost its lustre. After bouncing back from being a druggy haven, there was another lull in the early 2010s as some new restaurants and boutiques migrated to younger, buzzy neighbourhoods such as Bandra and Lower Parel to the north. But the draw of Colaba, according to Thakur, is unique, maybe made even more so because of its waxing and waning. “Colaba’s character, its feeling of old Bombay and its colour and vibrancy, has not gone away,” she says. “If anything, people are appreciating it more than ever.”

Irish designer Cormac Lynch directs us to his apartment with very specific instructions. “If you see a plastic chair, a half-built lift and plaster crumbling off the walls, you are in the right building,” he texts Monocle. Lynch has called Mumbai home for the past nine years. While his projects are usually modern, he wanted to lean into tradition for his own home. The main living room is painted a deep honeyed gold with buffeting curtains draped over the floor-to-ceiling windows. Whenever he mentions an artist friend or a fashion-designer acquaintance, he gestures to one of the buildings nearby, indicating the direction in which they live. “It’s an area that attracts the creative type,” he says. “It’s all this beauty around us.”

As the light begins to fade, we find ourselves drawn inexorably to the shoreline. People promenade, buffeted by a cooling sea breeze, while Colaba’s art deco jewels twinkle in the gloaming. Looking out across the water at the gleaming skyscrapers of modern Mumbai, it is easy to feel as though Colaba is still an island, protected from modernity by a strip of water. Sometimes it takes standing at a distance to see more clearly. Sellers hawk peanuts in paper cones; trousers are rolled up to let ankles cool in the water. A man flies a kite in the wind then hands the reins to his son. Mumbai or Bombay? Foreigners and maps will tell you the former but the locals feel differently. They say that Bombay is the feeling; Mumbai is the geography. If that’s true, then Colaba is a perfect mixture of both.

Colaba calling: Neighbourhood know-how

The cost of a one-bedroom flat and the estate agent to call:

Approx 18,000,000 rupees – 25,000,000 rupees (€200,000-€280,000). Call Meeta Singh.

The best street to live on:

Merewether Road. You’re a stone’s throw from Colaba’s finest art galleries and restaurants but one step removed from the chaos. Canopies of ancient trees lend afternoon shade to the apartments lining this lovely strip.

The school in which to enrol the children:

In nearby Fort, the Cathedral and John Connon School is a co-ed institution that dates to the 1800s and entices parents with its promise of producing well-rounded and academically formidable citizens.

The best grocer, baker and ‘vada pav’ maker:

Parsi stalwart Yazdani bakery is the place for hot, soft breads and Iranian chai; the bun maska combines both with added butter. But head to Swati Snacks for Bombay’s famous afternoon pick-me-up: vada pav is a dense potato patty stuffed between fluffy bread and swipes of spiced and sweet chutney. Enjoy it with sweet coffee.

The five galleries or collectors to meet:

1. Sakshi Gallery for a true Colaba institution.

2. Experimenter for exposed beams and something more contemporary.

3. Project 88 for a taste of Brooklyn in Bombay.

4. Jhaveri Contemporary for the brightest of the Indian diaspora.

5. DAG Mumbai for experiential art within the hallowed halls of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

The running route that shows the enclave at its best:

The 3km stretch of Marine Drive for its waterfront views and the unusual quiet you can experience – as long as you’re out early.

Closest airport and how to get there:

Fly into Mumbai’s transit hub, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport, and take a ride-share southwards. After 25 minutes, Colaba is in sight.

The biggest improvement in recent years:

The Eastern Freeway has shortened commute times across the city by half in some instances.

The area is still missing:

Green spaces dedicated to leisure and play (particularly for children).

One thing you’ll only find here:

A generations-old Parsi silver jeweller operating out of the curved window of an art deco jewel.

How to start a music festival

Pinkfish Music & Arts Festival

Malaysia

Before Kuala Lumpur-based entrepreneur Kesavan “KC” Purusotman co-founded Pinkfish with Rohit Rampal, his childhood friend and business partner, the duo had spent more than 15 years organising music events and concerts. “There was a demand for live music after the coronavirus restrictions were lifted so we decided to realise our dream of putting on a music festival,” says Purusotman.

The inaugural edition of the Pinkfish Music & Arts Festival in April 2023 featured international and regional headliners, from French producer DJ Snake to Malaysian rap star Joe Flizzow. In June 2024 the festival returned to the Sunway Lagoon theme park in Subang Jaya city, attracting some 15,000 attendees. “We wanted to focus on creating a unique atmosphere, one in which people could build a long-term relationship with the business and not just with the headline acts,” says Purusotman (pictured). “Music is the heart of every festival but it’s important to emphasise other elements too.” Purusotman also runs several satellite events under the Pinkfish umbrella, including Pinkfish Countdown on New Year’s Eve, indoor concerts and pop-up performances across Kuala Lumpur between its bigger calendar fixtures, from the Pinkfish Express (a party train featuring DJs playing in carriages) to artist sets in ice-cream shops.

The sense of community generated by these events is a crucial part of what makes the brand unique. “It’s what music is all about,” says Purusotman. “If you go to almost any other concert, you’ll probably sit down with a few friends to enjoy the show and then go home. But there are no fixed seats at a music festival, so it’s easier to meet new people.”

Large-scale events such as Pinkfish Music & Arts Festival are a boon for Malaysia’s tourism industry but strict government guidelines can make hosting them difficult. Earlier this year the Malaysian Islamic Party questioned why the Pinkfish Express event was allowed to take place on a state-owned train. Purusotman, however, believes that it’s possible to find common ground with the authorities. “There’s still a long way to go before we can realise our goals but the dialogue with officials is moving forward. I’m grateful for that.”

pinkfishfestival.com

The fairer music app

Even

New York

“I got lucky,” says Mag Rodriguez, reflecting on his 12-year career in the music industry. During his final year of high school, Rodriguez started managing a classmate who then broke onto the global rap scene. “We toured the world for six years,” he says.

When you meet Rodriguez in person, you get a sense of why he did so well as a manager: he’s easy to warm to. That magnanimous spirit is at the heart of his latest venture, Even. Most artists make little money from sharing their music on services such as Spotify. Even seeks to address the issue by offering music creators a “direct-to-fan” model. “With the major streamers, you can get access to almost every song ever created through subscriptions for about $12 [€10] a month,” he says. “But you can only split that fee in so many ways and the platform also has to take a cut.” On average, artists make about a third of a cent per stream.

Rodriguez says that Even isn’t seeking to replace the big streaming services. “I tell people to think of it like a cinema,” he says. “Artists release their album on the app seven to 30 days before it’s officially out everywhere else.” They can also encourage fans to buy their music by giving out rewards such as backstage passes.

Recently an artist making $700 (€630) per month from streaming earned $40,000 (€36,000) in 30 hours on Even. But Rodriguez (pictured) is equally excited by musicians who have gone from never making money from their work to earning their first $25 (€19).

Rodriguez is especially animated when he talks about the app’s community-building potential. Not long ago, he says, fans of one of Even’s artists planned to meet up before a gig. Tracking this through the app, the performer decided to make a surprise appearance. “Social media has created a false sense of how big fan bases are. But nothing beats realising that these are real people on the other side.”

even.biz

Making vinyl pay

Record Industry

Haarlem, Netherlands

Factory worker Jos van Wieren is carefully peeling a stamper negative from its “mother” disc when we meet him at Record Industry in Haarlem. The creation of stampers, which are used to press grooves into vinyl, is just one of the labour-intensive stages of making a record. “It’s like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” says the company’s chief commercial officer, Anouk Rijnders, striding through the 6,000 sq m warehouse.

Bubbling blue vats of solvent, sapphire and diamond cutting heads, and gleaming, direct metal mastering discs are all part of the process of turning PVC slabs (or “biscuits”) into records. From a special edition of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon to the tunes of Dutch rock band The Vices, this factory presses as many as 10 million discs per year.

Despite dire warnings over the decades that CDs, MP3s, online piracy and, more recently, streaming services would spell doom for the vinyl format, Record Industry has kept the decks spinning. “I have been working here for almost 25 years and this is probably the fourth time I have seen vinyl making a comeback,” says Rijnders. “It never really goes away.”

Founded as Artone in 1958 and now run by husband-and-wife team Ton and Mieke Vermeulen, Record Industry is a place where historic machinery meets modern automation. As an artist manager and record-label owner, Ton was a long-term client of the press before 1998, when Sony Music decided to sell it. He admits that he had concerns about the future of the business when he bought the factory. “It felt as though a new record plant was closing every month because of the decline in vinyl’s popularity at the time,” he says.

Record Industry’s status as a family enterprise and its commercial flexibility have been crucial to its survival. It can press about 40,000 discs a day, in as many as 20 different colours (or a mixture of them), and make records using plant-based bioplastics. The building is also equipped with a direct-to-disc recording studio, which regularly attracts musicians. It’s an elaborately furnished space, containing everything from Rijnders’ grandmother’s rug to hi-tech cutting equipment.

Mieke, who serves as Record Industry’s chief financial officer, says that the height of the coronavirus pandemic was a boom time for the company. “There were no festivals or concerts but people who liked music still wanted to spend their money on it,” she says. “A lot of people started cleaning up their house, starting with the attic, and found their record players. Putting on a record is not just listening to music; it’s quality time for yourself. If you listen to music on streaming services, you can go for hours without doing anything. But if you play a record, you have to stand up and turn it over. It’s mindful.”

Though demand has dipped since then, many continue to buy records to support their favourite artists. Staff members also point out that, though vinyl is a form of plastic, it is far from a throwaway item. “We’ve made our production process as sustainable as possible,” says Ton. “Our electricity is solar- or wind-powered and the gas that we use for our boilers is co2 compensated. Plus, the cardboard used for packaging is fsc-controlled.” For the team at Record Industry, the business is as much about sharing an enthusiasm for the format as it is the bottom line. “It’s something to hold, admire and be proud of,” says Rijnders.