Anyone seeking an authentically Helvetic home for the holidays this winter should consider swapping the grand hotels of Gstaad, Verbier and Zermatt for something less well-known. Set in the 800-year-old mountain town of Ernen in the canton of Valais, Michelhaus is a new property from Reto Holzer. The Zürich hair salon-owner purchased the three-storey building for himself in 2020 before opening it up to holidaymakers.

The chalet from 1686 was in dire need of renovation when Holzer bought it. Working with Valais architects and carpenters, he saved the original floors and the stone hearth that still boasts the coat of arms of the family who built the place. “The architects here are used to the complexities of renovating old chalets,” Holzer tells Monocle as he crosses the 350-year-old floorboards in a quilted Moncler jacket, his chocolate-brown poodle, Maxime, at his heels.

Once the bones of the building were safe, Holzer split the house into two apartments that can each sleep up to five people in plush Hästens beds. Antique milking stools, cowbells and paintings from brocantes contribute to the old-world decor, while Holzer also furnished the house with modern pieces including Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona daybed and Stella McCartney’s take on Mario Bellini’s Le Bambole sofa for B&B Italia. “This is a place for people looking for something rustic and cosy,” he says, opening the doors to the balcony. “I like the mix between old and new.” From our perch, we hear the tinkling bells of cows grazing in the field as Holzer points out the Finsteraarhorn, the highest peak of the Bernese Alps. “I like to come here because it’s quiet; life is slower.”

Ernen, a town of 550 people, is something of a time capsule. Until the Napoleonic era, this grassy patch of the Alps – less than a three-hour drive from Zürich and Geneva – was an important crossroad in the Mitteleuropean trade route. But the town’s importance waned when the Simplon and Grand St Bernard passes were built, improving cross-mountain travel.

Case in point: the unappetisingly named local dish of cholera. As we gather around the table for lunch, Holzer brings out the pie, filled with apple, potato, onion and raclette cheese — a hotchpotch of the limited resources that locals could access throughout the winters. Joining Monocle is the mayor, Francesco Walter – it’s a small town, remember – who has spearheaded Ernen’s music festival since 1998. “I have a passion for culture and saw the festival as an opportunity for tourism,” says Walter. “When I joined, it consisted of six concerts taking place over two weeks. Now we host more than 50 events a year.”

As a bottle of Swiss white is uncorked, conversation flows. Hunkered in Holzer’s chalet, the calm that might elude you in Gstaad, Verbier or Zermatt is as hard to ignore as the Alps out the window. michelhaus.ch

Holzer’s Ernen guide

1.

Hike the 4.8 km-long Twingischlucht trail in through the Binntal valley.

2.

Ski down from the Eggishorn in the Aletsch Arena, a large area for skiing and snowboarding in the Fiesch valley.

3.

Admire the earliest known depiction of Switzerland’s legendary archer, William Tell, painted on the side of the Ernen Tellenhaus.

4.

Sample the local cheese, the Binner Alpkäse, at Ernen’s organic food shop, St Georg.

5.

Learn about local history in the town’s Jost-Sigristen museum and the Tellenhaus.

For jeweller Gaia Repossi, it seems that creativity is genetic: her great-grandfather founded the Repossi jewellery brand in Turin in the 1950s. After studying painting and archaeology in Paris, she began to help her father at Repossi’s Place Vendôme atelier, and in 2007 she joined the business as creative and artistic director. Today, Gaia applies principles of art and architecture to her work, often breaking the rules of conventional jewellery-making to create contemporary pieces. It’s a breath of fresh air in an industry that is often bogged down by tradition. Access to Repossi’s rich archives also means that Gaia has unlimited visual references to inform her work.

Repossi’s flair for design translates to the way that she dresses, which is both elegant and conceptual. Here, she shares some of her biggest influences and explains why comfort is key in both jewellery and fashion.

Do you have any rules when it comes to getting dressed?

Follow your instincts. You should go for things that suit you. I prefer a more androgynous style and opt for a lot of menswear. I like to pay attention to what’s going on in the fashion world and make an effort to understand the trends. Ultimately, however, I focus on the brands that resonate with my own aesthetic. Fashion can feel very overwhelming and, at times, superficial.

Who are some of the designers you connect with?

The work of Bottega Veneta creative director Matthieu Blazy is fascinating. He plays with leather and creates new silhouettes. His clothes have become a uniform for me. I’m also drawn to Pieter Mulier’s designs for Alaïa and the way that they sculpt the body. I wear a lot of Phoebe Philo too. Her work is elegant but also feels comfortable and casual.

Does the way you approach jewellery design reflect your taste in fashion?

It’s all linked. The key to making jewellery relevant nowadays is to choose more contemporary shapes and silhouettes. Fashion speaks to the women of today and tomorrow, so why can’t jewellery do the same? The materials might be more expensive than those for making clothes but it doesn’t mean that you have to make classic shapes.

What advice would you give to someone coming to Repossi for the first time?

You’ll probably choose a ring as your first piece from us. Having a signature ring on each hand is a modern way of wearing jewellery. I’m also a big fan of ear cuffs. Jewellery should be comfortable and light. When you make the shape of a piece more abstract, it feels softer and more enjoyable to wear – just as with clothes. Comfort allows you to be yourself. If you’re constricted, you can’t move freely or express yourself.

How do your shopping habits change with the seasons?

I don’t buy that many things, just a few key pieces per season. I prefer to shop for vintage clothes as it is a more playful experience. I collect a lot of Gucci pieces from the Tom Ford era. They’re simple, well-cut and a little strange – perfect if you don’t want to dress like everyone else. We live in a world of [social media] influencing, where getting dressed is now a job. I try to stick to my own ideas, instead of conforming to trends. I don’t think that we’re interested in looking at products that way any more.

1.

Lilli Elias

Based in Amsterdam, Elias is the founder of Autumn Sonata, a line of towels and table linens launched in 2022, which uses antique prints to create heritage-inspired textiles

“A rule of thumb for Christmas entertaining? More is more. I always invite a few too many people, make too much food (including multiple desserts), pour a lot of wine and gradually turn the music up until it’s a little too loud, in the hope that dinner will transform into a party. Something that I don’t like at a festive gathering? Cold bare feet. Shoes should stay on unless the house is well-carpeted.

I like to have something light to drink before eating. A heavier digestif, such as cognac, should follow with dessert. Having said this, it’s important to know whether or not you are a good cook. If not, please spare your guests and order a takeaway.

So many dishes say winter to me but I particularly love brussel sprouts, roasted squash with pomegranate and chicories with herbs.

I’ll be in New York this winter and will inevitably end up at one of my favourite restaurants, La Mercerie, for indulgent dishes, festive drinks and an altogether delightful atmosphere. As much as I love white tablecloths, I have had to move on after one too many trips to the dry cleaners. I adore using patterned table linens from my brand, Autumn Sonata. I couldn’t survive without decorating a gingerbread house. I plan and gather inspiration all year round until I’m ready to execute.”

2.

Gerald Li

Li is the Hong-Kong based co-founder of Leading Nation, a hospitality group behind several fine-dining establishments across Asia.

“Excessive formality is something that I don’t want around the table. I like to keep it relaxed and fun; there’s no need for stiff manners. The host should always have one memorable bottle of wine to hand.

Roasted bone-in prime rib is the dish that always signals the holidays to me. The table needs ample wine glasses and enough plates and cutlery for each guest to ensure that there’s no mixing and matching. I don’t like fruit cake or panettone, so you won’t see them on my table. Maybe there’s a reason why they’re only served at Christmas. Family game night, which mainly involves Vietnamese mahjong, is the one thing that I couldn’t do without.”

3.

Jonny Gent

Gent is a painter and the founder of Sessions Art Club in London’s Clerkenwell and Boath House hotel in the Scottish Highlands.

“Candlelight is essential for a Christmas party, as is lots of hard liquor to loosen up your guests. You want gossip, laughter and tears of joy. The playlist is also key. It’s probably the first thing that I put together as it sets the mood for the evening. In terms of who’s coming to dinner, it’s all about intimacy and how much you want to squeeze into a short window of time. It has to be the closest of friends and family. You must adore their company. It should feel as though you’re partaking in a last supper, without the death bit, of course.

When it comes to setting the table, I pick the whitest of linen tablecloths because I love to see how filthy it gets by the end of dinner. I also always lay the table with napkins bought from Auldearn Antiques in the Highlands, which are embroidered with the initials of a dead aunt from Dundee.

My food intolerances include any dish cooked from a recipe on social media that isn’t made by an actual chef and any light bulb that has more than 1.5 watts. I feel a deep sense of love when I drag out the raclette machine. I serve it with grilled bacon, sausages and mushrooms. There are also piles of pickles and crudités, as well as a Swiss dip that my wife learned how to make while growing up in Geneva. The recipe is a secret.

I love the scrambling and constant movement of cooking and eating raclette. People waiting for the cheese to melt. The shame and horror as you try to pour it before it is ready.

For an aperitif and digestif, I’ll have a martini made by Indre from Sessions Arts Club, followed by a strong and creamy Irish coffee.

The tables that I’ll be booking this winter are The Yellow Bittern and Bentley’s Oyster Bar & Grill for late-December oysters and a prawn cocktail. The thing that I won’t be doing? Tuning in to the King’s speech.”

4.

Juliet Linley

Linley is a Trinidadian-Swiss broadcast journalist and former Vatican correspondent now based in Zürich. She’s also a regular on Monocle Radio.

“Dancing flames in the fireplace, candles on the dining table, warm petit fours to welcome guests in from the cold and an abundance of comfort food and drinks all say Christmas to me.

I have fond memories of sunny Christmases celebrated at my grandparents’ home in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. My brothers, cousins and I would gorge on pastelles [steamed cornmeal patties filled with mincemeat and capers and doused in pepper sauce] and doubles [cumin-and-turmeric fritters], eaten with curried chickpeas and tangy tamarind chutney.

Aperitivo? Always. Preferably sourdough bruschette topped off with freshly pressed olive oil, anchovies and burrata, and accompanied by with a glass of Tuscan wine. I’m heading to Tuscany before Christmas this year with my family. We’ll be visiting our favourite trattoria, Da Sandra. The owner, Sandra, makes all the pasta dishes herself, from fresh truffle tagliolini to gnocchi with porcini mushrooms and sautéed pumpkin. But our family favourite is her fillet with paper-thin slices of lard. It is quite simply melt-in-your-mouth glorious.

Sometimes, we have fish fondue for dinner on Christmas Eve, before heading out to Midnight Mass at St Peter’s Basilica if we are in Rome. We set the table with vintage fish knives, long-stemmed forks, earthenware pots for the bubbling broth, lots of home-made sauces and several platters of raw fish and shellfish. A traditional panettone is a must at Christmas. But a tasty Trinidadian black cake infused with dark rum also rings in the holiday season for our family. All I want for Christmas? A new Monocle tote bag.”

5.

Eduardo Aires

Aires is a Porto-based designer who was responsible for the city’s peerless graphic rebrand.

“Aperitif? Digestif? Both, with lots of unashamed joy, and, more often than not, a singsong. My only intolerance is last-minute shopping. It’s a waste of time, energy and money. Bad choices get made in a hurry.

As I’m from Portugal, the food that reminds me most of the holidays is cod. Growing up, however, my mother also used to make deep-fried, bow-shaped sweet pastries. My go-to winter restaurant to book in Porto is Cafeína. After dinner, I usually drop in on my favourite bar, Passos Manuel, in an old converted cinema.

For Christmas, I’d really like to finish my book. It’s about the design collaboration that I have been working on for the past 16 years with Esporão, one of Portugal’s biggest and oldest wine estates.

The only thing that I don’t want to see around the table is mobile phones. Christmas dinner is special, so I like to be able to look people in the eyes while conversing with them. It’s a time of year when I see people who I might have struggled to otherwise, so we sometimes have a lot to catch up on – a year’s worth of stories. I don’t want to ruin that time with screens.

I have a very special embroidered tablecloth that I only use during the holidays. It is from the island of Madeira and it took nearly three years to complete. When I put it down, it signals that the table is ready to be set. I’d love it if Christmas happened more frequently. It’s a catch-22. Perhaps it would make the holiday seem less special. But it would be nice to try to adopt these joyful family moments into our daily lives as much as possible.”

6.

Jean-Charles Carriani

Carriani is the co-founder of Rose Bakery group, the outposts of which include popular berths at Le Bon Marché and DSM Paris.

“The rules of basic hosting are to be friendly and a good listener; you should be happy to be talking to your guests. Aperitifs are also essential and should always be accompanied by goodies fresh from the oven. My winter treat of choice is a good bottle of English sparkling wine. When it comes to setting the table, I never forget the essentials: salt and a good bottle of red.”

7.

Christopher Tan

Tan is a former columnist at ‘The Straits Times’ and an award-winning food writer, cookbook author and cookery teacher.

“When it comes to hosting, pacing yourself is crucial. Whether you’re a host or a guest, quality is more important than quantity: good parties over more parties. In terms of food, I am spiritually allergic to poorly cooked turkey. It has to be marinated in some sort of spice paste. A really good deep-dish pie with a curry filling is what says Christmas to me. Tandoori-turkey malai tikka kebabs are the best, as is a really good traditional pandoro, which I slowly eke out – thin slice by thin slice – over the course of December. When it comes to setting the table, the less fuss, the better.

If I could have my own way, I would line it with banana leaves and make everyone eat with their hands. I can do without the weird jumpers too, which, thankfully, I don’t have to deal with in Singapore.”

8.

Oliver Spencer

Clothing designer and retailer Spencer founded his smart menswear brand in London in 2002 and recently opened a new shop on Marylebone’s Chiltern Street.

“Having some European family, there are two sets of rules for hosting at Christmas: European customs and English table arrangements. The host changes every year – we’re in Miami this year and, perhaps, Warwickshire the next – but cooking duties are always shared between different family members.

For me, Christmas is about bringing together the old, the young and those who are usually on their own. Dinners and festivities are a time to connect with one another – and everyone should be invited. We usually have about 15 people around the table.

I never have turkey for Christmas. Instead, I always opt for a good roast beef. My family likes to decorate the table with a simple tablecloth, dried fruit and cinnamon sticks. It’s seasonal, simple and makes the room smell good.”

9.

Michelle Chow

Chow is the founder of Pass It On, a design studio, gifting platform and brand of eco-friendly homeware based in Singapore.

“I believe in the three “R”s of hosting: respect, relax, and reuse. Respect for my guests’ tastes, relax to let conversations flow and, of course, reuse everything, from upcycled tableware to repurposed decor. I have an intolerance for plastic cutlery and single-use anything. The worst Christmas tradition? Plastic toys that get forgotten by New Year’s Day. I’d rather skip the gimmicks.

For drinks, I’ll open with something light and refreshing, such as Glug Glug’s vinho verde, and close with a digestif from Australian wine-pouch brand A Glass Of, which champions the work of independent vintners. For dinner, I’ll make a squash risotto with regional produce and garnish it with fresh herbs from the balcony garden. It’s a dish that always reminds me of winter.

The restaurant that I can’t wait to try this Christmas is Somma in Singapore [see number 11]. I’m not a huge drinker but if I do go out for cocktails, it’ll be at Fura. What I most want for Christmas is a two-week holiday and a visit to Kamikatsu, Japan’s “zero-waste” town.”

10.

Zeynep Fadillioglu

Fadillioglu is a Turkish interior designer based between Istanbul, London and Doha. In 2009, she became the first woman to design a mosque.

“When it comes to hosting, I enjoy mixing timeless tableware from brands such as Christofle, Baccarat, Rosenthal, Wedgwood and Ginori 1735 with vibrant, artisanal plates from the likes of Levant. Hand-embroidered tablecloths paired with colourful centrepieces from designers such as Carolina Irving add a wonderful dimension to the table.

I prefer to prolong the pre-dinner part of any festive gathering to allow for genuine interactions with my guests. The restaurants that I have designed all have lounge areas where people can enjoy their drinks before eating. This fosters a certain warmth that encourages people to continue on to their table. This winter, I’ll be dining at Canton Blue in The Peninsula. I’ll also visit Chiltern Firehouse for drinks and food.”

11.

Mirko Febbrile

Pugliese chef Febbrile is the Italian restaurateur behind Fico in Singapore’s East Coast Park and Somma in the city’s just-opened New Bahru development.

“Hosting is all about the little details that bring warmth and connection to a gathering. For me, a non-negotiable for every occasion is fresh farm flowers. I love chamomile, olive branches and artichoke flowers. I want to be with people who are on the same wavelength and value connection. Relationships deepen when we can share plates and conversation without expecting anything in return. We always make sure to have a selection of panettoni. They sit under the tree until Christmas. We usually end up with so many that they become a breakfast staple right through until February. My dad absolutely adores dipping his panettone into milk.

I love Christmas and everything that comes with it, from ugly sweaters to Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You”. Having said that, I have spent the past decade away from home, so I have learned to adapt to Christmas in Singapore without the usual traditions.”

12.

Alberto Alessi

Alessi is president of Italian design company Alessi Spa, which was established in 1921.

“I’ll be booking a table at Il Clandestino in Stresa this winter. Stresa is a small town on Lake Maggiore, which is crowded in the summer but quiet in the winter. Chef Franco Marasco offers the best fish in the area. To drink, I’ll start with a kir royale. Then a glass of good wine, preferably pinot noir, followed by grappa or aged calvados. My food intolerance? Tomatoes. French chef Alain Chapel’s chocolate cake is the dish that says winter to me.

This Christmas, I would like to be with my books. I’m proud of my collection, which includes titles on the history of my region, Lake Orta, Lake Maggiore and the valleys of Ossola. I have been collecting them since I was a teenager and now there are about 12,000 books and documents in my library, which I plan to make into a foundation. Aside from the newest pieces from Alessi, I’ll line the dinner table with a selection of old silver objects by British and Austrian designers Christopher Dresser and Josef Hoffmann.

In my opinion, the worst Christmas tradition is being with too many people. My mother, Germana, used to organise dinner at home for the entire family, which involved about 40 of us of all ages. She believed it was her duty and did it extremely well. But I found it unbearable and I escaped as quickly as possible.”

13.

Enrique Olvera

Olvera is a Mexican chef at the helm of Pujol in Mexico City, as well as restaurants in New York and Oaxaca City.

“Nowadays, I like to keep Christmas celebrations within a close circle of people. I also like going to houses rather than restaurants. I normally have a dinner party for my close team of collaborators and friends. During this time, I tend to visit Los Cabos, Mexico City and New York, which are my three favourite cities to spend the holidays in.

If for whatever reason you don’t want to host a party, it’s OK to skip a year of hospitality. That’s the beauty of Christmas and New Year; you get to do it all again the next year.

I like to start with some champagne or a non-alcoholic agua fresca with a dash of sparkling water, so you still get that feeling of celebration. After dinner, I’ll have what’s called a sobre mesa: time spent talking in the company of friends and family. It’s always nice to do this with a glass of mezcal or Japanese whiskey in hand. Romeritos, a leafy green herb that grows during winter in Mexico, always reminds me of Christmas. It is traditionally served with dried fish, prawns, potatoes and nopales [cactus]. There’s a lot of mole in it. I also like anything that is roasted. It’s something that tells me we’re in the Christmas season. I’ll often throw a bird, ham or mushrooms in the oven. I decorate the table with beautiful placemats made from the threads of Oaxacan agave. I like to do things family-style, so it’s important to have nice cookware. That way, you can leave the food in the pots that you cook it in. My mother used to make bacalhau, dried salt cold, which she would form with her hands into a paste. I prefer to keep the fish in bigger chunks.

In terms of restaurants, I enjoy going to Máximo Bistrot in Mexico City during winter. Eduardo “Lalo” García’s cooking is heavily influenced by French cuisine, so you can expect everything to be a little buttery. There’s also a lot of roasted produce. If I’m in New York, I’ll probably be at the bar at The Bowery Hotel.”

14.

Ralph Schelling

Schelling is a Swiss chef who has worked at El Bulli, The Fat Duck in the UK and Ryugin in Tokyo. He’s also a regular recipe contributor for Monocle.

“Bitter-leaf salad with slices of Sicilian orange is a must during winter. I enjoy hosting large dinners with handwritten place cards laid around the table. I’ll start the evening with an aperitif from Ghia mixed with agramonte gin, ginger and a little bit of cardamom.

My main food intolerance is fake butter – it’s a weird concept when you’re from cow country. When it comes to booking a restaurant this winter, I would recommend trying out Via Carota, a charming Italian trattoria in New York.”

15.

Jacqueline Ngo Mpii

Ngo Mpii is an entrepreneur, author and creative director. She is the founder of Little Africa, a Paris-based cultural agency that seeks to amplify African heritage in the French capital.

“As a new parent, all I want for Christmas is sleep and no cooking duties. Everyone is welcome for Christmas dinner. It is mainly a celebration for family members but it should also be offered to those who are considered to be extended family, which includes partners, friends and colleagues. This makes for a more interesting evening, with added stories and laughs.

I will, of course, have both an aperitif and a digestif. As we say in Paris, “C’est la base” [“It’s necessary”]. Make sure to leave plenty of time for conversation before the meal; an apéro is not an apéro if it lasts for less than an hour. Poulet DG, a special dish from Cameroon made with chicken, plantain and vegetables, always reminds me of Christmas.”

16.

Sandra Sándor

Sándor is the founder of Budapest-based fashion brand Nanushka. The label has become a flag-bearer for high-quality Central European craftmanship and design.

“I love to add volume and proportion to my tablescapes. I use chrome napkin rings and bold candle holders to offset an otherwise very simple, classic and neutral setting. I also have a large collection of vintage ceramic plates and bowls. Collecting vintage pieces has been a passion of mine for a long time. I have amassed them during my travels over the years.

Something that’s important to me is making my guests feel at home. I want them to be able to relax, so soft furnishings and comfortable seats are important, as is the right amount of candlelight. Mood lighting can really change the atmosphere of a space.

My favourite winter meal is túrógombóc, a Hungarian dumpling dish made from sweet cheese that’s boiled and rolled in breadcrumbs. It’s rich and delicious, and always feels like a treat. It gives me the sweetest feeling of nostalgia.

It’s tradition that we spend Christmas with my parents in Marbella. Since they are retired, they live there during the winter. Spending time with them is sacred and it’s something that I look forward to every year.”

17.

Kristoffer Juhl

Juhl is the co-founder and managing director of Copenhagen-based textile company Tekla, which creates soft furnishings, pyjamas, sheets and throws.

“My advice for the holidays? Be generous. Take the time to prepare things well. The food and the details are what make hosting fun. Linens are such an important part of a good table – luckily, Tekla makes great ones.

In the lead-up to the big day, Danes usually spend time with friends – old and new – and colleagues at a julefrokost [Christmas lunch]. In my family, our favourite festive dish is caramelised potatoes. It’s the perfect partner to the duck, turkey or pork that often comes with it. My grandmother makes amazing braised cabbage too. Schnapps is the digestif that helps us through the pickled herring and the fatty pork. You have to be careful though: for the inexperienced, it can knock your socks off.

All I want for Christmas is new pots and pans. And peace and harmony, of course. In Scandinavia, there’s a tradition of singing and dancing around the tree after Christmas dinner. I’m excited for my daughter to be old enough to do this.”

18.

Annalisa Rosso

Rosso is the editorial director and cultural-events advisor of Milan’s globally renowned design fair Salone del Mobile.

“For us, the magic rule is to have a maximum of eight people around our dining table. It’s the perfect number for a good conversation. All the other conventions can go out the window. We even talk politics at dinner.

It is always nice to meet new people. Friends of friends are welcome at our home. We try to match people up with others coming from different spheres of our life. Those who aren’t welcome are those who don’t have much of an appetite.

We like to host long dinners followed by a spot of limoncello, which we make from green lemons grown on the Amalfi coast. Frozen meals are, of course, a no. Pumpkin risotto with chestnuts is always a winter favourite.

This year, I’ll be booking a table at Trattoria della Gloria in Milan, which is run by Tommaso Melilli and his amazing crew. Then I’ll have a negroni sbagliato at Bar Basso. For Christmas, I’d like a secular version of a presepe, a nativity scene. ”

19.

Colin Chee

Melbourne-based Chee is the founder of Never Too Small, a design media company that spotlights smaller spaces occupied and decorated by renowned designers.

“We decided to start a new tradition by hosting a Christmas lunch in our cosy 40 sq m studio apartment. It was my partner’s idea to invite people over who find themselves alone during the holidays.

Melbourne, much like London, is a city where people come and go, so each Christmas, we welcome regulars as well as new friends. There are funny people, loud folks, introverts and extroverts – anyone who isn’t afraid of open conversation and can handle a bit of drama and fun. And as for who isn’t coming? Those who dislike dogs.

My partner is English and enjoys eating a roast, so I’m considering a West-meets-East feast for this year’s gathering: traditional roast pork belly with sweet soy-and-ginger sauce.”

20.

Elsa Ravazzolo Botner

Ravazzolo Botner is the director of one of Brazil’s leading modern art galleries, A Gentil Carioca, which has branches in Rio de Janeiro and São Paolo.

“Our collector friends from Naples are coming to dinner this year. They are great cooks and like to make struffoli, a special Neapolitan Christmas pastry, made from fried dough and honey. They also treat us to spaghetti with fish, minestra maritata soup and stromboli [bread stuffed with cheese and salami]. I use my trips to Milan as an excuse to bring back panettone. I have never found a good one in Rio.

I don’t really like Christmas decorations here: the fake snow and people dressed up as Santa seems a bit silly when it is 40C outside. It doesn’t make much sense. But the contrast is fun to see. Though I really think that Santa Claus should wear a bikini here.”

Dave Smoker, an Amish furniture maker, is intensely focused on staining a grand timber table. “I have always enjoyed art,” he says, sweeping his hair from his forehead and following the grain of the wood with long, meditative strokes of his brush. Smoker started work this morning at 05.45 and will not finish until 17.00, when he and his fellow Amish craftsmen will down tools and join their families at home for supper under the glow of battery-powered lights.

The Amish are an Anabaptist religious community – a Christian movement that traces its roots to the 16th century – that eschew cars in favour of traditional carts. Their homes are typically cut off from the electrical grid and they prefer to live apart from wider American society, content with farming, worshipping and dressing in the plain way that their ancestors did when they first landed on these shores from Switzerland and Germany some 300 years ago.

Yet the Amish and their less orthodox brethren, the Mennonites, are also some of the US’s best carpenters. They have made their own heavy-set utilitarian wares by hand for generations. Over the past few decades, Amish-made furniture has grown into a vast sector, with family-run factories and workshops dotted across the country and a whole industry dedicated to selling and shipping this work. As the owner of one US firm put it to Monocle, “These guys just know wood.”

This knowledge has seen the Anabaptist’s woodworking and joinery skills increasingly sought out by contemporary design studios across the country. Among them is Los Angeles-based Kalon Studios. Its contemporary chairs and tables have a crisp, functionalist simplicity and are designed to be timeless and sturdy enough to be passed down the generations. “The Amish and Mennonites have deep expertise about how each piece is built, which other workshops don’t always have,” says Michaele Simmering, who co-founded Kalon Studios with her partner, Johannes Pauwen, in 2007. “In Los Angeles, there is a large manufacturing industry but it’s a business of one-offs,” says Pauwen. “You can’t do sustained production.”

The US market for collectable and limited-edition design is booming, with new fairs and galleries opening coast to coast. Yet the middle ground – aspirational but accessibly priced furniture – is dominated by a few brands. This is partly because the US’s woodworking industry shrank during the 2000s, as manufacturing moved to Asia. Much of what remains has either been swept up by larger firms or is specialist facilities producing goods that are too costly to make in large numbers. Amish and Mennonite makers strike the balance, helping emerging studios to scale up while keeping their products made locally. “It opened up our business,” says Simmering. “Our number-one struggle was finding reliable, high-quality, consistent furniture production.”

California modernism might seem a far-cry from the lives of these country folk but, in the making of furniture, common ground has been found. Getting on the books of Anabaptist factories, however, is not so easy. Kalon Studios had to go through a rigorous vetting process by community elders before the craftsmen would agree to work with them, covering everything from the liquidity of their business to their “moral compass”. Indeed, monocle’s main concern reporting this story was that we could get all the way to rural Pennsylvania only to find a deserted workshop. “They might all just go home to avoid you,” said Kalon Studios before we headed there. These pious communities try to steer clear of anything that could be considered prideful.

Nevertheless, after six months of making our case, Monocle is in Pennsylvania and driving through an American pastoral of sunlit hay fields, porch swings and strawberry stands that line the side of the road. You know you’re entering Amish country because the electricity poles and billboards that feature on most US roads start to peter out. We soon pass tiny hamlets with German bakeries and Victorian houses. When we see a woman in an ankle-length dress and bonnet, watering the weedy flowers beside her post box and a teenager riding a bicycle with no gears (such mechanisms are deemed to be too hi-tech), we know that we’re in the right place.

Kalon works with several workshops in the small Pennsylvanian town of Lebanon (pronounced “Lib’nan” locally) to build some of its chairs and stools. It is a real family operation, with Earl Zimmerman – grandfather to no less than 53 children – at the head of the factory we visit, which has just celebrated its 50th year in business. When Monocle visits, a ripsaw is in action on the production floor, slicing through logs that will eventually be turned into seats. Raw slabs of Pennsylvania black-cherry wood from sustainably managed forests sit at one end of the workspace.

The Zimmermans are Mennonites who, unlike most Amish, own modern technology such as cnc woodcutters, have mobile phones and even run a website for the business. “But the computer is a tool and not a toy,” says Earl’s son Nate, who walks us through operations on the factory floor. He explains that such technology must be used warily and only if it makes the community’s work more efficient, therefore allowing it to continue its way of life.

Old-fashioned, hands-on skills are preferable and apprenticeships are a key part of the culture. Most children start learning a trade – whether that’s farming or joinery – while still in school. Nate’s son Trevor, aged 13 and on holidays, is at his father’s side. “We say that there’s a lot more caught than taught here,” says Nate. “Skills come from watching how the work is done.” Young Trevor has already adopted the unofficial uniform of the Mennonite carpenter: tucked-in shirt, pencils in his top pocket and a tape measure clipped to his belt.

For Kalon Studios, the Zimmermans are not just fabricators but collaborators, offering suggestions of how to hone their designs for greater longevity. The brand’s Bough stool was inspired by the sashimono woodworking tradition, which uses complex, concealed joinery to give it strength. This was developed by Kalon Studios over the course of two years. “It fits together really snugly,” says Pauwen, admiring one of the products. “There’s beauty in these joints.”

The scale and capacity of these firms have been steadily growing too. Mennonite factories in the US are now competing with European manufacturers for contracts, especially for restaurant-chain fit-outs with large orders. The Zimmermans have a second facility on the other side of Lebanon, which makes 350 chairs every week. “We have a reputation for longevity, which serves us well,” says Wendel Zimmerman, who runs the factory with his three brothers and maintains a trusted workforce of smartly dressed carpenters with exacting standards. Notable design brands now produce their work with Zimmerman, though many prefer to remain discreet about it – in part because competition for craftsmen is so high. Monocle’s recent collaboration with Collect Studio on a series of chopping boards and bowls was made here.

Wendel says that Zimmerman is receiving more requests from the design world but the company remains selective about who it works with, prioritising brands with repeat orders and what Wendel calls “good values”. “We will end up taking on more high-end projects in the future,” he says. “I hear from larger manufacturers that this has become a significant amount of their output.”

Case in point is US heritage brand Emeco, which has been working with Mennonite factories for 15 years. Best known for its all-aluminium Navy chair, Emeco joined forces with British designer Michael Young in 2010 to create its first-ever piece of wooden furniture, which was produced at Mennonite and Amish factories in Pennsylvania. “Finding these craftsmen was so important,” says Gregg Buchbinder, Emeco’s owner. “The Navy chair is made to last for 150 years, so the question was always how we could make a wooden chair with that kind of longevity too.” Today many of Emeco’s wooden products are machined in Mennonite workshops. “A lot of makers have exported their production overseas but having complete control and oversight of the process means that we can communicate to the market why ours is a better product.”

This is a concern for many emerging US design firms that want the way they make their products to be in keeping with the ethos of their brand. That can be in terms of sustainability (US-made products, while more expensive, don’t have to be shipped from the other side of the world) or a level of finishing. With regards to the latter, brands are at the mercy of the manufacturers that they partner with and, as a result, designs can often be watered down to fit the capabilities of a factory. Mennonite and Amish factories are helping to bridge that gap. At another family-run, Mennonite-owned workshop in Lebanon with a row of buggies lined up out front, Monocle finds Amish men in boater hats and braces working silently and diligently on a batch of dressers for Kalon Studios. “Our single strongest asset is our work ethic,” says the factory’s owner, Kevin Martin. “This is our contribution to society: our work is what we pay for the space we take up.”

With Mennonite factories, Monocle is told, you pay a little more for the service but can be assured that the work will be done on time – and that you aren’t getting ripped off. A popular psalm daubed on houses and mailboxes all over Amish country sets the tone: “The Lord does abhor the deceitful.”

In Sapporo’s Odori Park, the wind is howling, the temperature is minus 7c and snow is blowing horizontally. The competitors preparing their intricate sculptures for the city’s annual week-long snow festival, held every February, couldn’t be happier – the 78 teams of amateur snow sculptors know that warmth is the enemy. Since 1965, this section of the competition has been dedicated to local entries and the winner is voted for by the public.

It’s day five for the volunteer team from Toko Electrical Construction Co. Every day, two groups of 15 have been scraping and shaping a pile of snow into a giant image of Yubaba, the big-haired bathhouse proprietor from Studio Ghibli’s blockbuster Spirited Away. The team won in 2023 with the Catbus from another Ghibli film, My Neighbour Totoro, and are keen to do so again. Part-time snow sculptor Yasuko Kitada, armed with a clipboard, is in charge. “It’s warmer this year so it was quite difficult in the beginning but today is really cold – that’s what we want.”

Nearby, a team of artists is hoping that its sculpture of Japanese baseball megastar Shohei Ohtani will be popular with the voting public. With only a couple of days to go, tensions are high. “If there’s any melting, we’re allowed to fix it only once during the week before the judging,” says Kitada. She says that climate change is having an effect. “It’s warmer during the day now, even if it’s still cold at night.” Snow has been trucked in from mountains outside the city.

Further up the park are the out-of-competition sculptures, so professionally executed that it wouldn’t be fair to pit them against the amateurs. The top draws are usually the building-sized efforts – from the Taj Mahal to kabuki theatres – by soldiers from Japan’s Self Defense Forces (SDF). Some 3,600 SDF personnel stationed at nearby Makomanai are working on two epic pieces: one is a huge profile of characters from the Hokkaido-set manga series Golden Kamuy; the other is a recreation of old Sapporo Station, which was in use until 1952. By night, the sculptures are illuminated as vast crowds descend on the festival, with food-and-drink stands supplying refreshment.

The Snow Festival attracts visitors from all over the world, providing a welcome boost for the economy. This year there were 2.39 million attendees – numbers not seen since before the coronavirus pandemic. And the winner of the citizens’ competition? Yubaba, with Shohei Ohtani coming third. And with the top three teams gaining automatic entry to next year’s event, Kitada and her clipboard will be hoping for a third consecutive victory in 2025.

For centuries, Norwegians from all walks of life have been making their way to seasonal rural residences. These hytter (holiday homes) and årestuer (traditional huts) offer a base for favourite Norwegian pastimes of hunting, fishing, hiking and cross-country skiing.

With some 450,000 of these structures spread across the country (and one in three families in Norway owning one), it’s no surprise that some of the country’s finest architects are turning a hand to their design. Across the next few pages, we visit three outstanding examples.

1.

The blended build

Norefjell

Office Kim Lenschow

Cabin culture and the desire for a holiday in nature – whether a lengthy summer on the lake or cosy winter weekend – is not unique to Norway among northern European nations. But the development of the hytte is. This humble holiday cottage has its roots in the vacation habits of the country’s city dwellers and their desire to escape from urban areas, going off-grid in simple huts, so as to allow themselves to be immersed in Norway’s rugged landscapes. These forces are still present in the hytte of today.

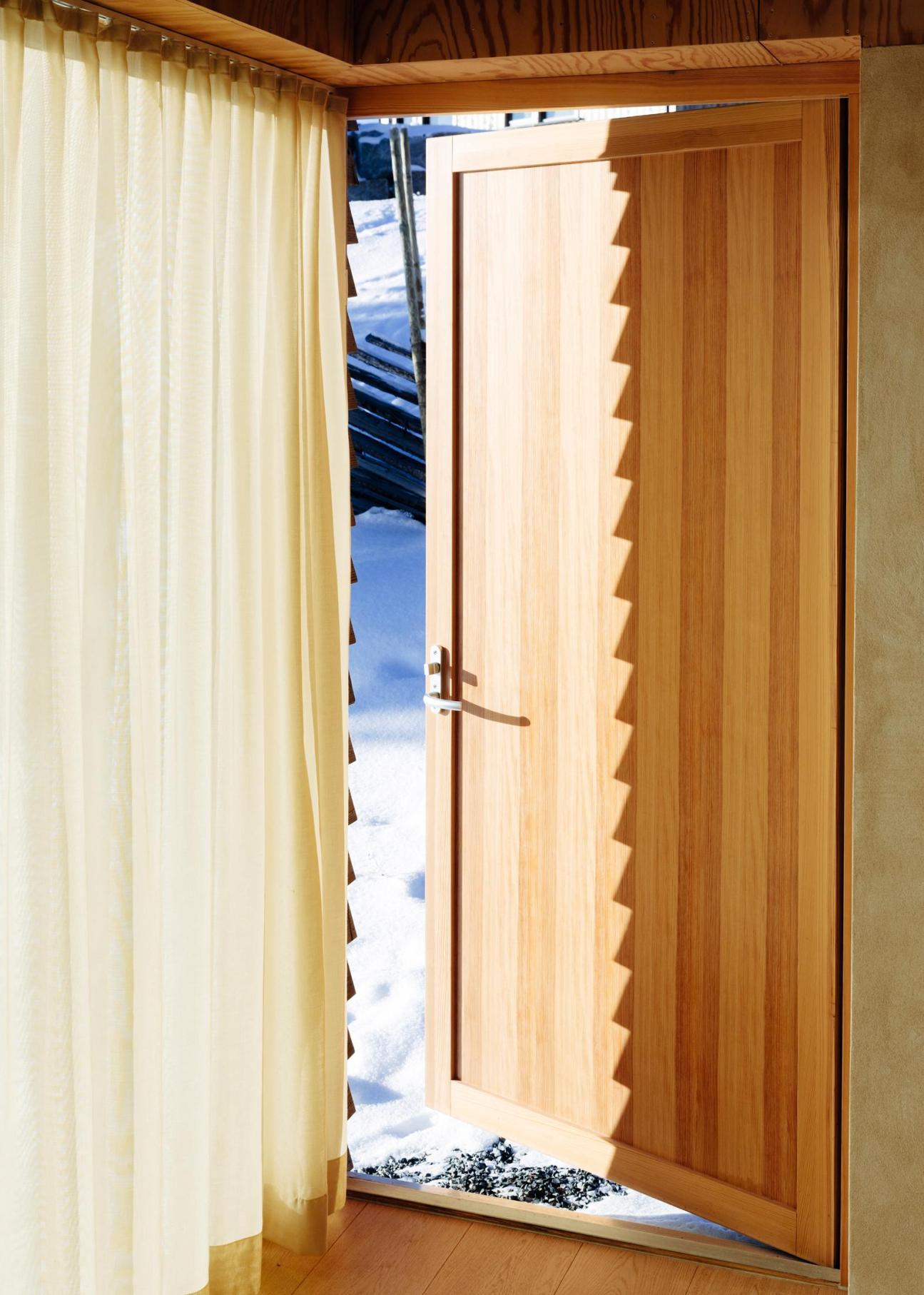

“These are places where you step out of your normal routines and live life differently, almost allowing yourself to be bored,” says Kim Lenschow of these countryside retreats. The Copenhagen-based Norwegian architect has recently finished one of these small, traditional timber holiday cabins in a rocky area northwest of Oslo.

Located 800 metres above sea level in Norefjell, this cabin was commissioned by a friend of the architect, who discovered the plot while searching for the perfect spot to build his own country escape. “This project was about bringing traditional elements of a hytte to life through modern construction,” says Lenschow, whose approach to architecture is defined by a desire to create harmony between the built world and the natural environment.

“The area surrounding Norefjell is beautiful,” says Lenschow. “You have this rocky terrain contrasted by spruce trees.” The architect adds that one of his guiding principles for the project was to ensure that the cabin complemented its surroundings. “We wanted to understand the relationship between architecture and nature.”

To explore this relationship, Lenschow identified the need for the building’s colour and materials to work in harmony with the surroundings. “Architecture and nature are opposites in a way, because you’re adding something to a landscape with a specific logic in mind,” he says. “So the most effective approach was to emphasise simplicity and use colours that complemented the muted tones of the woodlands.” The resulting palette of primarily earthy tones allows the home to bleed visually into the background, and is particularly evident in the exterior surfaces, which feature two distinct elements.

On one side, the façade is finished with a textured render applied over the underlying brick structure. This grooved, light-grey surface gives the exterior a unique character – and creates striking shadows on sunny days – without clashing with the rocky terrain on which it sits. “We wanted to add subtle details to make it clear that this wasn’t just part of the rock,” says Lenschow. “But it also could not be too bold.”

On the opposite side, facing the sloping landscape and expansive woodland, is a façade made from spruce sourced from the local region. The timber is treated using iron vitriol, which speeds up the initial decay of the wood to create a protective surface that can endure harsh winters. Connection with the landscape is enhanced on this side of the building thanks to three-metre-high windows that frame sweeping views of the surrounding terrain. To further intensify this relationship with the natural world, Lenschow positioned the building in such a way that the boulders and natural elements block sightlines to the road. “The surrounding rocks almost become part of the furniture,” he says.

The colour, material and windows have helped this hytte to blend into the landscape but Lenschow didn’t want to completely disguise the building, so he opted for a straightforward geometric design. “It wasn’t about coming up with clever shapes to camouflage the house,” says the architect. “I like it when a building is proudly a work of architecture but still resonates with the setting.”

It’s a theme that continues inside, where the hytte’s floors belie the challenging terrain on which it sits. Rather than smoothing out the plot, Lenschow designed the structure so that the site’s varied grade define its rooms, utilising single steps to act as dividers between them. “We worked with the natural levels of the ground to section off different spaces,” he says. A bedroom sits on one level and a living room on another, with a separate kitchen level creating the sensation of walking on uneven terrain as you move through the house. “You almost feel like you’re outside.”

The interiors are kept simple. Many of the rooms are clad in a light wood, which is bathed in natural light even during the darkest months of the year. There’s a sense of spaciousness too, with minimal furnishings – a mix of Nordic design classics and wooden pieces – complementing the building’s palette. “The furniture, like the building, is very simple,” says Lenschow. “It gives the space a cosy feel.”

Key items include a rattan and teak cabinet by Danish homeware brand Nordal, and a modular L-shaped sofa in cream that defines the lounge area. Next to it, a step leads to the dining space, which features a long wooden table surrounded by Bambi 57/4 dining chairs – a 1955 design by Rastad & Relling now produced by Norwegian furniture brand Fjordfiesta. Behind this, floor-to-ceiling windows with light-hued semi-transparent curtains diffuse light throughout the space.

For Lenschow, designing this hytte meant creating a new structure equipped with modern amenities, while preserving the traditional essence of an off-grid retreat by way of simple construction and a deep connection with nature. “What the modern country escape looks like is an ongoing conversation in Norway,” says the architect. “It’s not about going back in time; it’s about each individual’s interpretation of what it means to be immersed in nature. For some, this means having a cabin in a remote spot, only accessible by skis. For others, it’s simply about being surrounded by stillness. What a hytte means to you is very personal.”

kimlenschow.com

2.

The new vision

Årestua

Gartnerfuglen Arkitekter

“We believe that every building should have its own soul,” says architect Ole Larsen of Oslo’s Gartnerfuglen Arkitekter, a firm he co-founded with Astrid Wang and Olav Lunde Arneberg in 2014. “Our aim is to uncover the unique potential of every project, rather than applying a specific signature style to everything we do,” adds Wang.

Case in point is Årestua, a newly finished holiday home for a family, inspired by the traditional design of årestue: traditional wooden homes built around an open fireplace. Located in Telemark, a region southwest of Oslo, it has been built using traditional methods, with specialist carpenters carefully stacking timber logs to form walls. “This construction method was a beautiful way to connect architecture with its place,” says Wang.

It’s an approach that also allowed the architects to explore how traditional architectural vernaculars, such as the årestue, can be reimagined for modern living. “Traditionally, this type of cabin is quite dark and enclosed, a place to retreat to after a long day outdoors,” says Larsen. “We wanted to preserve some traditional elements while also being innovative.”

In response to this ambition, the house’s layout is organised into five distinct volumes that house the bedrooms and bathroom, all centred around a main living area fitted with a fireplace. Expansive windows frame sweeping views of the snowy woodlands, creating a seamless connection between indoors and the surrounding landscape. The furniture is carefully positioned to encourage connection around the central living area. “Using the space is about being together,” says Wang. “We’ve added large windows to bring in plenty of natural light. That transforms the space.”

There are also unexpected architectural interventions that respond to the habits of its inhabitants: a small outdoor staircase by one of the doors provides a cosy spot for the family to enjoy classic Norwegian clover-shaped waffles while taking in the view. Additionally, one of the connecting rooms, elevated above the others, includes a window specifically positioned for observing the eagles that soar around the cabin.

“Building the right cabin is all about the small details,” says Larsen. “As an architect, it’s essential to keep an open mind when designing a cabin and to let the location and the inhabitants shape the space.”

gartnerfuglen.com

3.

The simple space

Mylla

Fjord Arkitekter

Despite its proximity to the city, the landscape surrounding Oslo remains largely unspoilt, characterised by mountains, vast stretches of forest, occasional lakes and cross-country ski trails. And though the area is dotted with cabins to which those in the Norwegian capital retreat during the holidays, for the architects practising here, creating buildings that have a “light touch” is essential to preserving these environmental qualities.

It’s something that Oslo-based studio Fjord Arkitekter has done with aplomb on a cabin project called Mylla. The design of this contemporary hytte is rooted in simplicity and sustainability. “The construction is made simple and rational,” says Fjord Arkitekter partner Finn Magnus Rasmussen. “And the materials are durable and natural.”

For proof, he points to the exterior, which is clad in pine treated in the Møre Royal style, a time-honoured Norwegian method that involves vacuum-cooking the wood in oil, creating a durable and weather-resistant surface that ages gracefully. This approach reduces the need for extensive ongoing maintenance or harmful chemical weatherproofing treatments. The hytte also uses a geothermal heating system. But, recognising that green credentials mean little without quality space, the architects have prioritised a calming interior. Oiled spruce walls and ceilings create a warm and inviting atmosphere, while a central sculptural staircase divides the space into zones.

“The cabin is elongated and narrow for the best adaptation to the plot,” says Rasmussen. “It provides distance between the quiet and active parts of the cabin. It might have a sober exterior but when you get inside, it is rich in spatial qualities.”

fjordarkitekter.no

“I’m a man of product,” says Damien Bertrand, the CEO of LVMH-owned luxury house Loro Piana. “Whether it’s haute couture, cosmetics or textiles, I love to feel exceptional quality.” Monocle meets Bertrand in his neutral-hued office in central Milan, which has been his base since he took up the post three years ago. It is filled with the kinds of well-crafted products that he is so fond of – Loro Piana’s signature Bale bucket bag, for example, and the men’s sharp Spagna jacket. We also spot the winning entry of this year’s Loro Piana Knit Design Award: a cashmere sweater inspired by knights’ armour, made by two students from the École Duperré in Paris.

“I’m sorry that the winners ended up being French, OK?” he says with a smile. Bertrand grew up in the south of France. He went on to serve as managing director of Christian Dior Couture for five years, after a stint in the US working in the fast-moving world of cosmetics for L’Oréal Group. “Every morning, on my way to work, I would walk past the Loro Piana shop on Madison Avenue and find it so intriguing. I would go in to touch and feel the products, so I developed a sensory knowledge of the brand a long time ago.”

That’s perhaps why Bertrand adjusted so quickly to life in Italy and dived headfirst into the CEO job, asking to visit all of the company’s factories in Piedmont, tour its global boutique network and speak to its clients to deepen his understanding of the brand, which was founded in 1924. “I remember ending up in a client’s dressing room until 02.00, looking at Loro Piana jackets that were more than 25 years old,” he says. “They were absolutely perfect. He knew exactly when he had bought them and how many times he had worn them, which was plenty.”

It was clear to Bertrand that he had a gem in his hands but he also sensed that there were “a few things missing”. Loro Piana needed to modernise its campaign imagery, develop stronger womenswear and accessories businesses, and become a bigger part of the fashion zeitgeist. “We set out to create a vision that would position us at the pinnacle of luxury,” he says.

A mere three years later, he is already well on his way to achieving his goal, with several sell-out handbag designs, new jewellery and sunglasses collections and a quickly expanding global clientele that has become “addicted” to Loro Piana’s feeling of quality – whether it’s the supple suede of the label’s boat shoes, the fine cashmere of its polo shirts or the ultra-soft Gift of Kings wool used to craft its sharp Traveller jackets, trench coats, lounge sets and more.

A lot of work has also gone into adding a more contemporary flair. The Loro Piana team has always been obsessed with producing the best textiles but it has now become equally fixated with refining a new signature silhouette: relaxed, perfectly draped and designed to always hug the body of the wearer. “We’re a house of no logos, so how do you create a recognisable silhouette?” asks Bertrand. “We had beautiful products but not this type of modern silhouette. That was the hardest thing to do but it affects everything, including the brand image.”

The CEO points out a photograph from a recent campaign that’s hanging on his wall. It shows a couple lounging in Scotland, wearing matching riding boots and tweed-and-wool ensembles. “It’s more contemporary but, at the same time, it’s very Loro Piana,” says Bertrand. “And you can tell the quality of the boots and the sweater jacket that he wears.” He adds that, since Loro Piana began to present its men’s and women’s collections together and establish a stronger dialogue between the two, the company, which had hitherto largely focused on menswear, has been able to attract a wider female clientele. Textile innovation is another key ingredient in his recipe for success. Under Bertrand’s watch, the business has introduced new textiles such as cash-denim, a mix of cashmere and Japanese denim that is used to create some of the world’s softest, most luxurious jeans, among other denim items. This summer, Loro Piana also debuted pieces featuring graphene, a heat-absorbent material obtained from graphite, mixed with wool to create durable performance wear. “Our clients love spending time outdoors so we created a new capsule,” says Bertrand. “The combination of natural fibres and performance is very rare but I wanted to enhance the brand’s reputation for innovation.” He stresses, however, that such developments require time and can only be rolled out in small quantities.

That isn’t how fashion brands tend to do business today – especially if they are part of a publicly traded company such as lvmh with financial targets to hit every quarter. But the rules are clearly different for Loro Piana, which seeks to position itself at the highest echelons of luxury. “Today many companies use the 101 marketing playbook, where you appoint a famous creative director and then dress a star for the red carpet,” says Bertrand. “But that kind of thing isn’t always aligned with our dna. Loro Piana isn’t Dior and Dior isn’t Loro Piana. The ethos here is about discretion, subtlety and sophistication.”

That’s why Bertrand has made a point of avoiding quick fixes, such as celebrity placements or runway shows, in favour of a longer-term view. “Our clients are connoisseurs,” he says. “There’s that famous saying: ‘If you know, you know.’ Though our brand name isn’t written anywhere, people recognise the quality and details.” All of this comes at a cost: €3,200 for a wool jacket, for example, or €16,000 for a shearling coat. What does he think of those who argue that the price tags are unreasonable? “They are not Loro Piana customers,” says Bertrand, who is perhaps the most knowledgeable customer of all and claims to be able to identify his brand’s cashmere in the dark just by feeling it. “They haven’t experienced the quality to understand it. We’re masters of fibres, so the idea is that you’re buying a piece that will carry you through a long stretch of your life. Some artists even tell me that they can only compose music in Loro Piana clothing, because of the feeling of confidence that it gives them.”

Bertrand applies the same luxury mindset to his management style, taking time to execute projects to perfection, paying close attention to minuscule details and daring to place bold bets. It’s why he hasn’t tried to expand the business’s retail footprint too quickly, despite increased demand across the globe. “What we’re doing instead is making sure that we have our boutiques in the best locations – Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles, for instance, has just reopened,” he says. “If we are offering the crème de la crème of products, we need to offer the crème de la crème of experiences too. I’m not in a hurry. The beauty of my job is that I don’t have to rush to create beautiful things, such as our pop-up in Zermatt. That was a first for us but it became the talk of the town.”

Bertrand’s approach is clearly working. “We’re seeing dynamic growth that’s quite balanced in every region,” he says. Luca Solca, a senior analyst at wealth-management firm Bernstein, tells Monocle that Loro Piana has been “one of the best brands in the lvmh group in recent years. It caters perfectly for high-end consumers who are veering towards casual wear, in the most elegant, sophisticated and expensive way possible.”

The increased visibility of the company’s pieces on social media and hit television programmes such as Succession has also played a part in the transformation of the business. This type of publicity often proves to be a double-edged sword, with the buzz dying down as quickly as it was generated and customers moving on. Can Loro Piana sustain the momentum at a time when fashion seems to be preparing for a return to maximalism?

Bertrand is certain that the only way is up. He says that the leather-goods and accessories departments that barely existed three years ago will continue to grow and debut new hits. At the brand’s most recent presentation – at Milan’s Palazzo Belgioioso, where elegant tailoring was paired with pillbox hats, silk scarves and new iterations of the loafer – the CEO’s ambition to offer a head-to-toe Loro Piana look while growing in all accessories categories was clear.

He is also confident that conversations taking place online and the direction of trends won’t affect his brand’s customer base, which has a different set of priorities. “Social media can sometimes create a sort of hyper-visibility all on its own,” says Bertrand. “You can be aware of it but you can’t control it.” He adds that Loro Piana products are limited by their nature and will never suffer from online oversaturation. “We don’t often work with influencers but, if people want to talk about our pieces, I welcome it because it’s interesting. We’re not loud but we don’t need to be silent.” This was the attitude that guided Bertrand’s decision to take over 36 windows at UK department store Harrods from 7 November to 2 January, to ring in the festive season and celebrate the brand’s centenary. This takeover at one of London’s busiest retail destinations is far from quiet; yet, in true Loro Piana fashion, the designs of the windows are elegant, logo-free and utterly charming. The idea was to create a “workshop of wonders” and tell the story of the company through wooden figurines, as though the pages of a children’s storybook had come to life. One window, for instance, showcases the journey of vicuña wool from animals to atelier and then finished product.

“Loro Piana’s discreet, logo-free approach speaks to a clientele that values substance over spectacle,” says Simon Longland, fashion buying director at Harrods, who praises the label’s sense of precision. “It captures the magic of the season without relying on overt branding. The success of its accessories lines has set new standards in the industry and its influence on contemporary footwear design is evident. And these categories are just the beginning. There is substantial potential for continued growth, as the brand deepens its offering in soft accessories and other luxury lifestyle products.”

The concept of an open book presented across the Harrods windows is particularly poignant; it is perhaps a subtle statement of Loro Piana’s confidence in its manufacturing practices, after allegations surfaced earlier this year that the company was sourcing vicuña wool for its garments from unfairly remunerated indigenous workers in Peru. The brand has since responded with statements of fair payments – between $300 (€277) and $400 (€370) per kilogramme of vicuña wool, according to a statement – and stressed its commitment to working in Peru, not only to refute the accusations but to honour the 30-year relationships that it has built with the country’s farmers.

“Our aim is to limit our environmental impact and safeguard the future of the next generation,” says Bertrand. “We have been doing this for many years but our efforts are intensifying. For instance, in Aqueripa, we created water reserves in 2018 to protect the animals and help the communities [which were suffering from droughts]. At a time when people are spending more and more time on their phones and might think that the world is virtual, we want to emphasise the beauty of the artisan world.”

It has been 100 years since Loro Piana started as a family business of wool traders and merchants. Both the brand and the fashion industry have completely transformed since then, with Loro Piana now owned by the world’s biggest luxury conglomerate and evolving well beyond its original textile business. Yet, for Bertrand, the label’s core values of family, quality and sophistication remain very much intact. The Arnaults, the powerful French family behind lvmh, have been long-time customers and fans, so they respect the company’s founding ethos and Bertrand’s signature strategy of evolution versus revolution.

That’s why, for the year ahead, Bertrand is focusing on “consolidating the vision”, rather than trying to keep up with market changes. “That is a part of luxury: knowing where you want to go and not looking left and right,” he says.

In many ways, Bertrand’s philosophy serves as a reminder of what luxury fashion should stand for at a time when too much attention is being paid to logos, seasonal hits and items that serve as status symbols. “Luxury is something with soul that you buy for yourself, not for others,” he says. “It’s like the private dinner that we hosted in Lake Como and didn’t communicate. Or, as Sergio Loro Piana would have said with his signature humour, we really should be talking more about quality and less about luxury.” loropiana.com

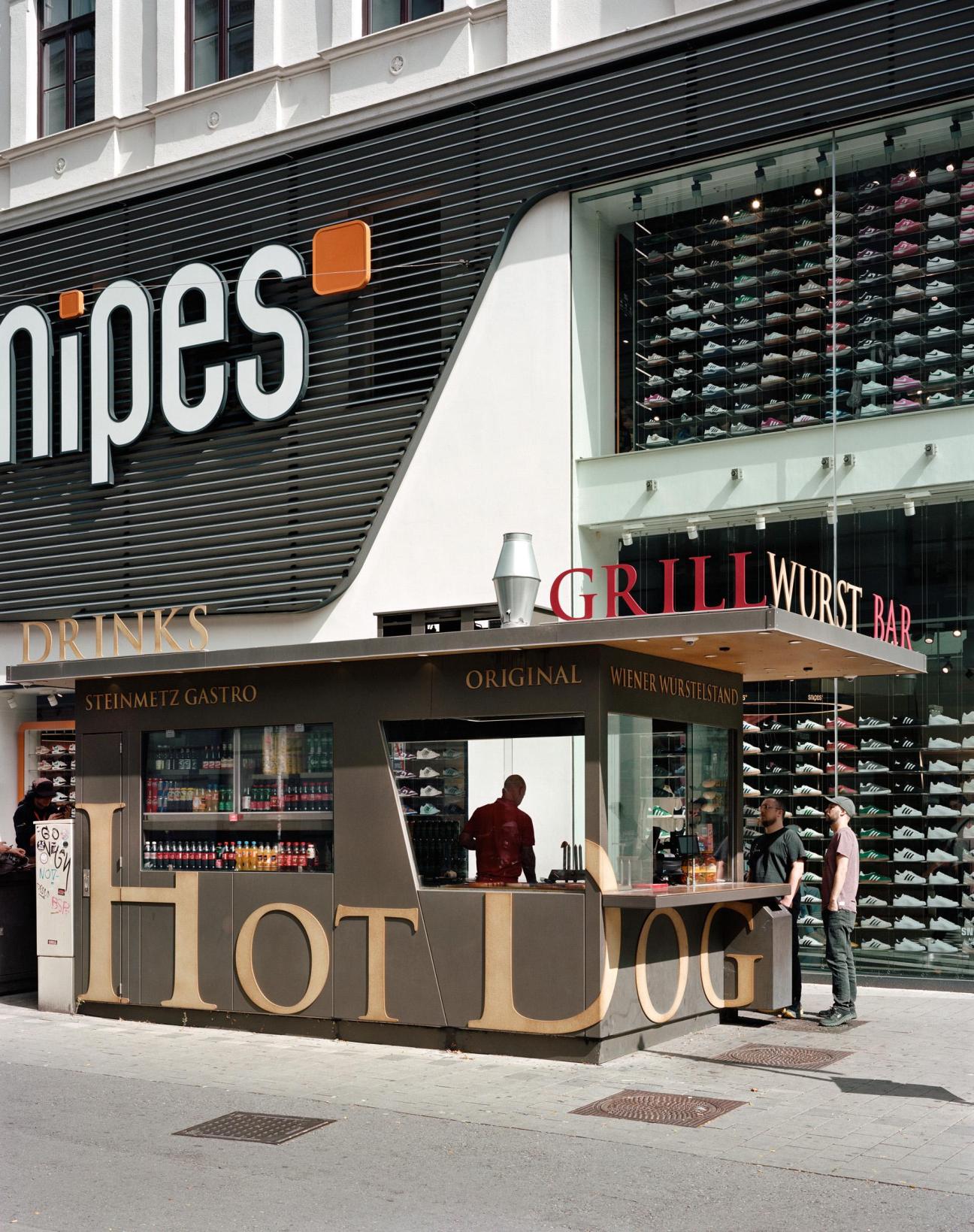

Austrian photographer and Monocle regular Stefan Oláh is known for his sharp eye for façades and interiors but also the lesser-known idea of “transit architecture”. He shoots non-places and hidden spots, the spaces in between that come to define cities by accident rather than by design.

The first edition of his photo book on Vienna’s Würstelstände (sausage stands) was titled The Hot 95 and was released in 2013 by historic publisher Verlag Anton Pustet. But that was just the beginning of Oláh’s obsession. This autumn a batch of new images was displayed at a branch of Radatz, one of Vienna’s best-known butchers, which supported the book’s publication then and now (and, of course, supplies many of the sausage stands depicted). In a testament to the Würstelstände’s place in the collective heart of Viennese residents, the city’s mayor Michael Ludwig – one of several opening night dignitaries – arrived early to quiz Oláh about his work. “I told him that there’s always a bin beside the stands,” Oláh tells Monocle. “But no two stands have the same type of bin or system of garbage disposal. He found it quite amusing.” The Würstelstände is also a reflection of the way in which unplanned elements and ideas often define cities better than slick marketing campaigns or the best-laid branding plans.

As with Oláh’s previous project on petrol stations, his examination of sausage stands has allowed him to look closer at his city and glean deeper insights about it. Studying sausage stands also reveals deeper truths about Vienna’s urban life and changing appetites. “A lot of the stands now offer organic food and beer, and the kiosk designs have changed too,” he says, showing Monocle one of the newer images, of a stand called Zum Goldenen Würstel (“At the Golden Sausage”) in the city’s postcard-pretty Innere Stadt. With a sleek metal-and-glass roof over the counter and large windows, it’s strikingly different from the old boxier kiosks. The oldest stand still in operation is said to be Würstelstand LEO in the Ninth District (now turquoise and perhaps not precisely as it was in 1928). The idea of the sausage stand is said to date back much further, to the Austro-Hungarian empire, with some sources even suggesting that the concept was cooked up as a way for wounded veterans to earn a crust. “There’s a lot of history here,” says Oláh. “A new generation of entrepreneurs has entered the business since I published the first edition.” Some stands have their own tribes too, such as opera-goers’ favourite Bitzinger, exhibiting angular modernism in the shadow of the Albertina museum, or the bright yellow Bad Dog near the Belvedere Palace, which is particularly popular with visitors from Asia.

The ongoing project, like almost all of Oláh’s work, can be slow-going. It requires a certain degree of patience given that no one quite knows how many Würstelstände actually exist in Vienna – Oláh and his assistants simply searched for kiosk-shaped structures on a map, then visited each to see whether it was a stand. Then there’s the weather. For one stand, at the atmospheric address of Am Nordpol (“At the North Pole”) in Vienna’s Second District, Oláh waited two and a half years to get the right shot. “I wanted to capture it in snow and it took that long to get the perfect conditions.”

Typically, Oláh’s frames include few if any people but, when they are there, they could really be anyone – a nod to another essential aspect of the Würstelstände: its egalitarian nature. Their clientele cut across social and cultural boundaries. It’s a cliché but an accurate one: at any given time, blue-collar workers, tourists, celebrities and politicians can be seen standing shoulder to shoulder. Even the word “wurst”, or sausage, is embedded in everyday speech: “Es ist mir Wurscht” – a quintessential Austrian phrase – translates roughly to “I don’t care” and is used by everyone. The Viennese can seem gruff at times but the humble sausage stand is one way to understand the city’s history, economy and appetites more intimately – and get some change from a €10 note.

Why the sausage stand?

Stefan Oláh’s fascination with the quirkier parts of the built environment began about 15 years ago when he started work on Sechsundzwanzig Wiener Tankstellen, a book documenting another Viennese curiosity: petrol stations tucked into residential buildings. His aim was to show how these stations – more than 26 of them are featured in the book, though many have since vanished – were an idiosyncrasy of his home city and an odd intersection of the old Imperial world and a newer, more mobile one. He was drawn by the unusual layouts and vintage signs, many dating back to the postwar decades. The book, published in 2010, sparked a flurry of interviews. In one of these, Oláh mentioned he might next turn his attention to another Viennese fixture: the Würstelstand. “It was just a passing remark,” he says. “But the publishers kept on asking: so when are you going to do it?”

Five of Stefan Ólah’s favourite Vienna sausage stands

1.

Hermann’s

5-7 Stiftgasse, 1070, in the Wipark Garage

2.

Wiener Würstelstand

1 Pfeilgasse, 1080

3.

Alles Wurscht

1 Börseplatz, 1010

4.

Würstelstand Kaiserzeit

Augartenbrücke/Obere Donaustrasse, 1020

5.

Zum Scharfen Rene

15 Schwarzenbergplatz, 1010

Wurst practice: sausage-stand etiquette

Ordering is an art, as is knowing your Senf (mustard) from your Semmel (dense white bun). Most sausages will be a frankfurter or bratwurst but other options include the cheesy Käsekrainer, long thin Sacherwürstel and smoked Waldviertler. Berliners will recognise the currywurst (as it sounds, drenched in spiced gravy) but the spicy Hungarian-inspired Debreziner might be news to you. While not compulsory, beer is a fundamental part of the Würstelstand experience – especially since, with their late-night opening hours, they might be the only spot to procure one should the mood strike. Among the classics is Vienna’s own Ottakringer beer, alongside other Austrian brews such as Wieselburger, all of which are typically served in a can.

A dusting of powder blows over Utah State Route 210 as Monocle drives up the canyon from Salt Lake City. Mountains loom above, covered in white snow and dark trees. Bound for Snowbird ski resort, a 1971 gem of modernist architecture hidden high in the Rocky mountains’ Wasatch Range, this stretch of highway is among the most avalanche-prone in the US. Road closures are frequent and the 30-minute drive from the Utah state capital is best navigated with sturdy vehicles (Monocle opts for an enormous, chauffeured black GMC Yukon).

“Snowbird is the first studiously modern American ski resort,” says Jack Smith. The Fellow of the American Society of Architects, now 92, was instrumental in the design of this pioneering destination, as an original member of the Snowbird Design Group. More than 50 years after opening, its bold concrete architecture – which includes several large, multi-purpose lodges, a hotel and conference centre, resort operations facilities and even a fire station – still feels contemporary. “Concrete is a miracle,” explains Smith. “You mix gravel, sand and water and get the hardness of stone. You can use it to make something special that has not been seen before.” Indeed, when it was completed, nothing like Snowbird had been seen before in the US, with its angular, modernist buildings emerging from the contours of the rocky, mountainous landscape.

“It erupts from nature, rather than imposing on it,” adds Smith, explaining that Snowbird’s building forms and materials suit the character of the mountains. But perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Little Cottonwood Canyon, where Snowbird is located, was formed by the immense force of millennia-old glaciers, carving out exceptionally steep slopes that have made its ski runs some of the world’s most thrilling – and conditions that make this landscape very difficult to build on.

But it’s this tough terrain that first drew Snowbird’s founder, Ted Johnson, to the area in the mid-1960s, when he took a job at the neighbouring Alta Ski Resort. Known as the “Silver Fox” for his good looks and mane of light-grey hair, Johnson was a thrill-seeker on skis and appeared in now-classic Warren Miller-directed ski movies and on the cover of Sports Illustrated (twice). But he also carried a similarly adventurous streak in his business dealings, as evidenced by his moves at Snowbird.

Fuelled by a desire to create a truly unique ski experience in Utah, on terrain so steep that it initially seemed impossible to develop, Johnson and his wife, Wilma, began to research the prospect of building a resort in the canyon. After identifying that the landscape where Snowbird is located amid US Forest Service land, crossed by a host of different historical mining claims (land titles that allow private development), the duo set about trying to collect all of the claims.

“Wilma went to the records office in Salt Lake County to research the claims,” says Neil Cohen, Snowbird’s official historian and retired 52-year-old veteran manager of the resort’s Golden Cliff Restaurant. The Johnsons slowly bought the claims and, in 1964, approached Smith, a friend and fellow avid skier, to start design work. Initial consultations took place in secret (to avoid others laying claim to the, well, claims) and the Snowbird Design Group was formed – a motley crew of architects and others passionate about skiing and striking gold with a new kind of resort.

In addition to tapping Smith, Johnson also hired Ted Nagata early in the process to give Snowbird its graphic identity. The Japanese-American graphic designer’s “wing” logo, with Snowbird printed in Helvetica above it, is now a classic example of 1960s American graphic design. This branding was instrumental in developing “the black box”, a paper pitch deck for investors that Johnson used to raise the first $400,000 needed to start the development.

By 1967 the Snowbird Design Group had created the first master plan. And from the outset, it was clear that the resort was designed to be different. “Ted Johnson said, ‘I’m not going to have that European chalet motif,’” says Cohen. The resulting designs were bold and angular, influenced by modernist masters such as Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier and the pragmatic utility of the illustrious US Army 10th Mountain Division, who had brought recreational skiing back to the US after the Second World War.

Like Marcel Breuer’s 1969 modernist masterwork Flaine Ski Resort in the French Alps – an inspiration to everyone involved – Snowbird developed its own design language. Dictated by a topography that left little room for buildings, the design group prioritised structures that fit into the terrain rather than fighting it. With no space to sprawl in the steep canyon, initial construction in the early 1970s saw buildings rise taller than other typical ski resort architecture. But careful siting below the interstate highway and along the contour lines ensured hat the massive structures seem smaller than they are.

Key to this approach was the master modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley, a mentor to Smith, who provided key input in suggesting the “skiers’ bridge” over Little Cottonwood Creek, which divides the canyon. The bridge seamlessly connects the ski slopes directly with the centrepiece Snowbird Center, one of the first spate of buildings completed for the opening day on 23 December 1971. The megastructure contains ski facilities and dining, alongside the base station of the Snowbird Tram.

Also among the facilities open at Snowbird’s inception was the now-beloved aerial tram. One of the first of its kind in the US, its blue-and-red cars travel 884 vertical metres to the top of the resort – an area known as Hidden Peak – in 13 minutes. Built by workers from Swiss lift company Garaventa (who brought their own liquor to Salt Lake’s dry Mormon country), it was – and still is – the most efficient option for transporting skiers to the peak.

This foundational work proved to be (unsurprisingly) expensive, and Johnson needed more cash to make his vision a reality. The most significant investors was Texan rancher, oilman and adventurer Dick Bass. Initially coming on board in 1969, Bass spending more than $13m on the resort by opening day. Development continued at pace, with the constellation of architects responsible for Snowbird evolving to include the likes of James Christopher and Ray Kingston. Bass became patron saint of Snowbird, buying Jonhnson out in 1974.