I had an aunt who never married or had children. There were suitors. Tennis partners that had been around for decades. They would often be at her house when we visited, dashing, and with stories from how they had met during the Second World War. But there were parts of her interior life that nobody was allowed access to. Even my dad, her brother, was always annoyingly ill-informed. But then he wouldn’t have made it on to a list of life’s big sharers.

Myrtle worked in the media. Her job was sending stories by telex, a skill – speedily and accurately dispatching information – that she had learned while working for the Royal Air Force during the war. I always liked being around her. She did her own thing. And one of these things was travel.

While my parents were securing the use of a caravan in Wales or perhaps – hold on to your hats – a cottage in Cornwall, Myrtle was heading to the airport. India, Canada, South Africa; off she would go. And I cheered her on because, as a young boy, I knew that she would bring me a souvenir from her travels. From Canada – I guess I was about eight – she gifted me a piece of varnished bark from a pine tree that had two plastic bears glued to its surface. A vignette from the wilds and clearly the best thing in the world when you’re eight. From India there was a snake charmer’s flute made from reeds and a dried gourd, a carved wooden elephant and a fan made out of peacock feathers (divine but not something that any young lad could use in public).

Myrtle purchased fancier things for herself that would find a place on her sideboard or bookshelves. And there they still were when I was a man, her gentleman callers long gone, and she was sliding into dementia. When the time came to clear her house, I kept her photo albums, filled with pictures from her travels in the late 1940s and 1950s. And I kept some of the souvenirs that had been sitting in the same spots for years. Items that, to the end, I hope, offered her a way to go back to a place and time that had long since receded over the horizon. I now have the white alabaster Shiva from India, a stone mountain goat from Canada, a woven bowl from South Africa. And while my gourd cracked long ago, so to speak, I still have the elephant and a tiny wooden giraffe.

The meander down memory lane this week has been in part promoted by another round of letting go. Neither me nor the other half have any parents left, both had child-free aunts who died (old age, not poisoned for the inheritance) and we’re both prone to sentimentality, so our garage is rammed with boxes containing things that nobody needs but which are hard to throw away. Stuff that just lingers. But this time we’re going for it. This week his aunt’s childhood teddy – bald, blind and with stuffing exiting the seams – has been given away for free to a woman who says that she offers bears a second chance at life. An ornamental decoy swan that belonged to my mother has also flown off to a new home after 16 years in a box. Ebay, Freegle, we’re on it. But those souvenirs from the 1970s and 1980s are going nowhere.

Last week I wrote about my visit to the Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi, about this place that houses a church, synagogue and mosque, and about its spiritual potency. I left out the bit where I went wild in the gift shop that’s run by the design company Fount. It has lots of nice things made in the UAE, including a series of simple wooden animals. I bought the oryx, which is now standing majestically on the kitchen table but might have to bunk up with the elephant in the coming days.

I know that it really makes no sense, forcing a swan and a bald bear to move out one minute, then guiding an antelope into the house the next. But I blame Myrtle. The souvenir is much maligned but, like her, I see in them a way of reaching back to a place and a moment. And perhaps, in my dotage, a way of looking up at a shelf and connecting to a different time.

Spanning 12 palm-leaf volumes of text and illustrations, the Serat Centhini manuscript is one of the treasures of Indonesian literature. Written in the early 19th century under the supervision of the crown prince of Surakarta, it is both a story and an encyclopaedia in which characters wander the island of Java, learning about the world.

Within the pages – alongside advice on Islamic practice, how to have great sex and farming – are detailed instructions for making use of teak trees. The number of branches, the surroundings of the tree, the presence of flowers and animals making their home in its trunk all influence what the wood is best used for, be it a column in a house to bring family harmony, the frame of a mosque to bring calm or a storage chest to bring wealth.

Today Indonesia is one of the world’s biggest teak producers. The timber is renowned for the beauty of its colour and grain, and the natural oil that helps to protect it from termites and the weather. These elements form the core of Philippe Delaisse’s business, Ethnicraft. All of its teak is sourced from responsibly and carefully managed forests. “The way that we win and ensure we’re competitive here is by embracing the raw materials and craftsmanship,” he says.

Enchanted by beautiful teak objects he came across while travelling in Bali in 1995, Delaisse began to export antiques and local crafts, before quickly jumping into production. He started in 1996 in Rembang, East Java, where he found skilled woodworkers willing to work with recycled teak taken from old buildings. “They used very basic tools and a lot of great craftsmen were working barefoot,” says Delaisse. From this emerged a series of beautiful teak cabinets and, piece by piece, the rest of Ethnicraft, the business that he and his business partner, Benoit Loos, have built.Trade wars and the long legacy of the coronavirus pandemic have increasingly pushed companies making products in Asia to explore manufacturing options outside China. But so far, Indonesia has struggled to get a look in: complex trade barriers, tricky labour markets and corruption meant that many companies went elsewhere.

Buffeted by the current trade war, the government is signalling reform. If it is serious, Indonesia has a lot to offer: a large and young labour force, a wealth of natural resources and pockets of deep expertise in various industries and crafts, of which woodworking is one. In a country where the previous president, Joko Widodo, built his fortune selling chairs, sofas and beds to the world, the hope is that others will follow.

Ethnicraft is showing what’s possible. Its main operations hub of some 1,600 workers is in the coastal town of Tegal. The setup here might feature high-precision machines, sturdy safety shoes and modern production lines but the dedication to material and craft remains rooted in tradition. The process always begins with the wood. Ethnicraft buyers scour government-owned teak plantations across Java for the best logs; competition is fierce, with rivals trying to poach the choice specimens. Transported and stacked in the lumber yard, each log is tagged with a QR code with which the company can trace the exact provenance of the tree down to a few metres, ensuring both sustainable sourcing and careful inventory management.

Next the logs need to cure – dry out – until they’re ready to be worked on. With teak, this is traditionally done by simply leaving the fresh lumber out in the sun for about three to four months. Once it is sawn into planks, it then dries for another month before spending a final few weeks in a vast oven. Other woods such as jackfruit and mahogany have their own timelines. The process is painstaking because the products being made demand precision. Wood “breathes”, expanding and contracting fractionally – and planks with different moisture levels will do so in their own ways. For precise work, a moisture difference of more than 1 per cent is unacceptable.

Then comes the craft. A few hundred kilometres away in Jepara, a workshop of about 600 staff produces furniture for some of Europe’s top luxury brands. Along this stretch of northern coast below the slopes of Mount Muria, woodworking skills are particularly sought after.Under a canopy of wooden beams, the process unfolds as the wood moves from turners to carvers and then to woodworkers, before being polished and varnished several times over. In their hands, simple planks, rough to the touch, are turned into exquisite tea boxes, sinuous ornaments and elegant furniture with a texture like heavy silk.

And it is very much hands doing the work. The processes here involve minimal modern technology. While a few high-precision machines have been installed, sheer skill gives the workers an uncanny exactness in their movements. At one bench Marsudi leans over an exquisite panel of wood that will become a luxury chess set. He has worked here for 24 years and the work is in his blood. “My kid also works here as a carpenter,” he says.

This tradition of generational craft is important, says Marsudi. “It helps a lot because of the skill that is needed; we’re working at a scale that is calculated down to the millimetre.” Everyone who enters the workshop must pass a rigorous test. But when such high levels of skill are required, growing up living and breathing wood helps. As we walk away, Marsudi bends over a gameboard that he is shaping. “He’s supposed to be a supervisor,” says Delaisse wryly. “But he just can’t stay away from doing some of the work himself.”

This ingrained culture and the pool of expert labour that it sustains is attracting many brands to manufacture furniture in Indonesia. Despite a rocky few years in the global economy, the furniture industry remains strong. International and local entrepreneurs and businesses alike jostle for production capacity. This includes Giovanni Gallizio, who operates another furniture factory in Jepara, producing to order for clients globally. “The manual dexterity and skill of the people here is outstanding,” he says. “There are few places in the world that have anything similar.”

China and Vietnam have reputations for being more efficient, says Gallizio, and that attracts many producers focusing on the low to middle end of the market. But he thinks that few manufacturers there possess the skills to match the sort of high-end work that can be produced in Indonesia’s teak heartlands. While Jepara is the zenith, skilled workers are present across Java. Back in Tegal, Delaisse’s other factory hums with activity: not just a world of sawdust, glues and varnishes but also one of metalworking, glass staining, stucco spreading and upholstery. “I’ve worked across the world and I’ve never seen a factory like this before,” says Steve Hauters, general factory manager, with a touch of pride.

The quest to ensure quality at every stage means that as the product line has evolved – from elegant chairs in plain wood to minimalist modular sofas and elaborately patterned trays – the number of processes performed in house has grown too. From planks to pillowcases to packaging, everything is checked and rechecked at 65 quality-control stations. Such practices fly in the face of much received wisdom about how to do business: in the name of efficiency, the usual advice is to specialise. But Delaisse says that his philosophy is that the product is everything, ahead of concerns about efficiency or marketing. “If you have an interesting product, do not spend too many resources on sales. The world is a very big place. Customers will find you.”

Other companies might come to discover the virtues of doing more in-house too. “I think futurewise, a vertically integrated brand is very valuable,” Delaisse says. Control over the process gives a wealth of data to analyse. And, in a world where fashion trends move fast, it lets companies experiment with greater ease.

The restless experimentation continues. In Tegal production of a new line of Morpho furniture for the music festival Tomorrowland is taking full advantage of the factory’s ability to combine wood, fabrics and metals in elegant designs. Back in Jepara, the firm has a new factory producing micro-cement. Spread it over foam and fibre glass, and you get a smoothly attractive and deceptively light stone-like slab that’s perfect for tabletops.

Still, the older traditions remain. Decorative woodcarving – one of Java’s most appealing arts that adds grace notes to mundane objects such as doors, window shutters and benches – is seen throughout the Jepara workshop. A coffee table is chiselled with irregular lines that ripple before the eye. Exquisitely patterned cabinets are making a splash in the Chinese market. And a series of elegant one-off pieces, each unique in its design and patterning, waits quietly for the right customer to find them.

This article originally appeared in the Opportunity Edition newspaper 2025, created in collaboration with UBS for its Asian Investment Conference in Hong Kong.

1.

Le Doyenné

Saint-Vrain, Île-de-France

Distance from Paris: 47km

Mode of transport: Car

Time spent travelling: About an hour

Direction: South

Aussie chefs James Henry and Shaun Kelly made a name for themselves in the restaurants of Paris. But after years in the kitchen, they turned to growing organic vegetables on their farm in Saint-Vrain. Housed in a lovingly restored barn, Le Doyenné opened as a restaurant and guesthouse in 2022 and has had a fine following ever since. Inside the restaurant, glass-paned walls provide views of the garden.

The menus change with the seasons, starring the likes of raw peas in spring and juicy tomatoes in summer. “What works one week won’t work the next,” Henry tells Monocle. “But when we came here our aim was to be self-sufficient and express ourselves.”

ledoyennerestaurant.com

2.

Le Barn

Bonnelles

Distance from Paris: 49km

Mode of transport: Car

Time spent travelling: Less than an hour

Direction: Southwest

The main lobby of Le Barn, a 73-room hotel southwest of Paris, doesn’t have a reception desk or a grand sweeping staircase but rather a wooden shelf, lined with Aigle wellies. The sight sets the scene for a stay at this rural retreat. It is nestled amid a sprawling 200 hectare site, complete with paddocks, a vegetable garden and a pond.

Le Barn opened in 2018 and has become a favourite weekend getaway for Parisians. Guests typically arrive on Friday afternoon in time for goûter or apéro but it’s on Saturday mornings that the place really comes to life. Outdoor yoga classes are held beside the pond and weekend plans are made over breakfast on the verdant terrace.

Rather uniquely, the hotel is nestled within Le Haras de la Cense, a distinguished stud farm. Other hotels in the region boast luxurious château settings but this one offers the chance to immerse yourself in nature and get up close and personal with the site’s horses.

“We didn’t want to block off access to the stables or riding arena,” says Franco-American entrepreneur William Kriegel. “The routes are the same for everyone, whether you’re a hotel guest or a student at the Haras de la Cense.”

Kriegel bought the estate in 1980. His decision to expand the stud farm into a hotel came from his desire to offer an innovative hotel concept that was an alternative to the country house, while still offering a closeness to nature.

“The aim was to create a place with a countryside feeling,” Kriegel tells Monocle. “I wanted to have simple architecture and use humble materials.” So, he teamed up with Antoine Ricardou of Parisian design agency Saint-Lazare to devise Le Barn’s aesthetic. After an influential research trip to Montana, the look and feel of the hotel took shape. Many of the bedrooms are arranged in two bright-red barn-like structures with walls clad in cork and wood; meanwhile, a custom-built tiled stove warms the lobby. “US ranch culture was a major inspiration but we were conscious of avoiding anything that would look too faux Western,” says Kriegel. And, though guests have the opportunity to book outings on horseback and pony rides for children, the hotel is just as suited for cycling enthusiasts, hikers or those seeking to do very little.

lebarnhotel.com

3.

D’une île

Rémalard

Distance from Paris: 160km

Mode of transport: Car

Time spent travelling: Over two hours

Direction: Southwest, towards the Perche Regional Natural Park.

“We have borrowed from the codes of classic hospitality,” says D’une île’s co-owner Théophile Pourriat. “But our vision is more relaxed: we simply host in the way that we like to be hosted.” While a lot of care is put into offering a personalised service, D’une île is doing away with many amenities that are traditionally associated with hotel stays, such as a porter or zippy wi-fi; even mobile phone coverage is unavailable. True to the inn’s rural setting – in the Perche National Park – the 10 guest rooms feature rustic decor that appeals to urban sensibilities but doesn’t clash with the historical facets of the 17th-century former farmhouse.

“We describe D’une île not as a hotel but as our maison de campagne,” says Pourriat. Together with his business partner, Bertrand Grébaut, Pourriat is better known in hospitality circles as the co-founder of Septime, a Michelin-starred restaurant on Paris’s Rue de Charonne. Branching out from drinking and dining wasn’t something that the duo had previously considered. But after staying at D’une île a number of times, they decided to take over in 2018. In Paris they were used to daily changing clientele, here they have more time to finesse the guest experience. Food, of course, is central to D’une île; it’s more a restaurant with rooms than rooms with a restaurant.

Pourriat and Grébaut put a lot of care into distilling the region into their cooking rather than infusing the countryside with Paris. Running a rural inn means that they can anchor themselves in the community and forge close relationships with producers. In the city, they relied on a network that stretched the length and breadth of France. All of the ingredients on the vegetable-centric menu at D’une île are from local farms and markets. Most of the fruit and vegetables are grown in the on-site garden and the fish comes from the Chausey Islands. Kitchen staples such as olive oil and lemons are replaced by Perche rapeseed oil and vinegar. “Whether the way we do things is the future of hospitality is unclear; there will always be space for palatial hotels where everything is available at all times,” says Pourriat. “But for us, this close-to-nature approach is fundamental to who we are as restaurateurs.”

duneile.com

4.

Tuba Club

Les Goudes, Marseille

Distance from Paris: 786km

Mode of transport: Train

Time spent travelling: Five hours

Direction: Make for Marseille by rail then hop in a cab

Since opening in 2020, Tuba Club in Les Goudes, a pretty fishing village just south of Marseille proper, has quickly become a summer institution in France’s second city. Founders Greg Gassa, an entrepreneur, and film producer Fabrice Denizot saw the potential of this no-frills former swimming club. They lured a smart, younger crowd to soak up the laidback atmosphere amid dramatic rocks and lemon-andcream-hued loungers. The founders tapped their childhood friend, architect Marion Mailaender, to take the bones of a bathing club and create something to match Marseille’s sultry summer mood. The brief? A friendly space that riffs on Le Corbusier’s wooden cabin at Roquebrune-CapMartin and the fetching bar that neighbours them, L’Étoile de Mer. In 2023, Tuba Club added a new villa to its five fuss-free Cabanon-style huts, providing an ideal platform to dive into resident chef Sylvain Roucayrol’s excellent cookery.

However you look at it, Zohran Mamdani’s victory in the Democratic primary for mayor of New York is a marvel. A 33-year-old state assemblyman with barely four years in office handily defeated Andrew Cuomo, a former three-term governor who was discussed as a formidable presidential contender just five years ago. Cuomo had much of New York’s Democratic party establishment in his corner, while Mamdani had the city’s Democratic Socialists of America chapter in his. Many prominent billionaires, including former mayor Mike Bloomberg, paid for advertisements attacking Mamdani. Cuomo’s allies spent, at last count, $36m (€30.7m) on the race; Mamdani’s just $9m (€7.6m).

How Mamdani managed to pull it off is no mystery. The Uganda-born son of a Columbia University professor and an Oscar-nominated filmmaker monomaniacally focused his message on the ways that the largest US city had become unaffordable for working-class people. Mamdani’s platform consisted of a handful of bold if fanciful policy promises – free buses, a rent freeze, city-run supermarkets – that he said would bring down costs. It was a pitch that Mamdani made in unconventional venues, such as on podcasts with sceptical hosts, alongside a charming social-media campaign that didn’t look like anything else in politics. A 90-second video in which Mamdani interviewed food-truck operators about why they had increased the prices of their meat-and-rice plates – a type of “halalflation” – became an instant classic of the form. The candidate suggested that the problem could be fixed by loosening regulations.

Mamdani turned most of Cuomo’s advantages against him. Backing from big business demonstrated that the former governor had picked the wrong side in a populist conflict. Endorsements from other politicians (including Bill Clinton) became evidence of unimaginative establishment-style thinking; his decades in government were suddenly an albatross around his neck. The contrast between Cuomo – who departed the governor’s mansion amid scandal in 2021 – and the upstart half his age was best captured in a Murray Kempton line that John Lindsay, another young, dashing mayoral candidate, put on his campaign posters in 1965: “He is fresh and everyone else is tired.”

For Democrats beyond New York thrashing about for a new direction after the Biden-Harris debacle of 2024, Mamdani’s success offers plenty to mull over. Should they move further to the left or lean into class-war politics? Perhaps a focus on cost-of-living and pocketbook issues is the way forward? As they seek candidates for 2026 and 2028, should they look past traditional credentials and connections, and instead recruit outsiders unsaddled with the baggage of the party’s previous leaders? Is the most valuable communication skill not the ability to give a speech or navigate a debate but fluency in the language of Tiktok and podcasts?

There is plenty to study and probably only so much that can be learned. If Mamdani ends up beating incumbent Eric Adams in November, the spotlight will not be his alone. The likely winners of the year’s two other big races – for governor of Virginia and New Jersey – will cut a very different profile. And what works in the politics of the Empire City famously does not travel well. There is a reason that it has been more than 150 years since a former New York mayor went on to win another office.

As Democrats dive into localised neighbourhood data in a bid to forensically analyse Mamdani’s unlikely path to victory, they shouldn’t overintellectualise the nature of his appeal. A winning personality goes a long way.

Issenberg is Monocle’s US politics correspondent. For more insights into Mamdani and the New York mayoral race, click here.

Tucked behind a red velvet rope in an inky side room off the main lobby, Le Bristol After Dark is delightfully unexpected – as if stumbling into a secret speakeasy in a palace. The nightclub stands in stark contrast to the famed 100-year-old hotel entrance – a grand space with ornate chandeliers, plush fringed couches and a painting of Marie Antoinette. In comparison, the club is lit with pink-and-purple neon lights, disco balls shining overhead. Partygoers sip Ruinart champagne and DJs spin disco and lounge tracks until the early hours of the morning.

The perfect balance of tradition and trend is what allows Le Bristol to maintain its reputation as one of Paris’s most legendary hotels. Set in an historic building and a hop away from Parisian icons such as Palais Garnier and the Tuileries Garden, the iconic property has hosted everyone from Coco Chanel to Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí. Now celebrating its centennial, Monocle meets president and managing director Luca Allegri to discuss how the hotel maintains its relevance in an ever-evolving hospitality landscape.

100 years of business is no easy feat. How do you stay timeless in a world that’s moving so quickly?

We try to surprise our guests with new ideas – art, for example. [American contemporary artist] George Condo, a longtime guest, collaborated with us on the renovation of the Imperial Suite. We asked whether he could leave a small piece of art with us when the suite was ready. We have also hosted a pop-up with Gabriela Hearst, who has been staying with us since she was at Chloé. When she launched her own brand [10 years ago], we began a partnership with a retail installation. [Now, a decade later, another pop-up has been launched in a space created by Benji Gavron and Antoine Dumas of Gavron Dumas Studio.]

There are some clients who only come to the hotel for Le Bristol After Dark. [The club] is a way for us to show that, while we have been around for a century, we are also contemporary.

How do you maintain a strong heritage aesthetic while always offering something new?

The owners are heavily involved in decorating the hotel, which allows them to preserve its DNA while bringing some novel elements to the style. We are very privileged to have plenty of space, which has enabled us to increase the number of junior suites and bathrooms (two per suite). After speaking to our clients, we learned that this was what they wanted the most.

What kind of experience do you want to create for your guests?

A distinctly Parisian one. We are located in the heart of a neighbourhood with the most popular galleries and attractions in Paris, so we also attract the city’s residents with our food-and-beverage offerings. We have launched our own in-house bakery with a mill in the basement, where we produce our own flour for bread. We now have a chocolate factory, pasta-making facilities and a cellar too, [which is] likely the largest wine cellar of all the Parisian palace hotels. It’s about giving guests a unique experience with a level of personalisation that they won’t find elsewhere.

We want to give our visitors an incredible experience not only in Paris but throughout the rest of France as well. I’m the son of a concierge, so I understand firsthand how crucial this role can be. Interacting with clients and creating meaningful moments are the most important aspects of our jobs. On Wednesday afternoons, we host cocktail parties where we invite some of our frequent guests to meet different team members, such as the concierge, the guest relations or the rooms divisions [managers]. They mingle and meet other clients too – sometimes they even become friends.

How are you managing your staff and their experiences in a way that might differ to other notable hotels?

Leading by example is very important. We have members of staff that have been with us for 30 to 40 years. When employees reach a milestone – such as 20 or 30 years of service – we invite them to celebrate by bringing their family to the hotel or organising a party. We’re a family-run business, so we like to give [the staff] a sense of belonging and community. Le Bristol is not just a hotel or home for the owners – it’s also a home for the staff.

How have you adapted to changes in guest preferences to ensure the hotel’s continued relevance?

Some 30 to 35 per cent of our clients are returning guests and we want to show them that their future stays are as important as their past stays. For example, we have a family from New York that has been staying in the same suite for the past 25 years. To show them how much we appreciate their loyalty, we approached them during the renovation of the suite to share the plans with them. We then designed the layout of the room together and they changed the placement of the bed. For us, adapting is a way of honouring such loyalty.

Mangia bene, ridi spesso, ama molto: of all the events on the annual fashion calendar, the famous Italian adage meaning “eat well, laugh often, love a lot” is never better encapsulated than at Milan’s Menswear Fashion Weeks. The biannual showcase is a week of serious work for brands, buyers, journalists and stylists alike but that doesn’t stop some seriously thoughtful entertaining. After all, in Italy, working hard and enjoying oneself are not mutually exclusive.

Given the show-to-presentation ratio during the city’s menswear weeks, Milanese brands have ample opportunity to flex their hospitality muscles. At the most recent spring/summer 2026 showcase, there were no fewer than 39 presentations compared to only 13 physical runway shows. The key difference? Presentations provide the chance to make an impression for longer than a 10-minute runway outing, letting Italy’s seductive approach to hosting shine.

Tod’s, for example, took over its regular haunt, Piero Portaluppi’s 1930’s masterpiece Villa Necchi Campiglio, and transformed it into the Gommino Club (named after the iconic Tod’s driving shoe). Here, the pattern-cutting demonstrations came with cocktails and generous chunks of parmesan. Meanwhile, at Montblanc’s space, train carriages designed by director Wes Anderson were filled with the brand’s leather goods and guests were invited to take a closer look while sipping fizz cooled with Montblanc-shaped ice cubes.

At Ralph Lauren, a Milanese palazzo was complete with a silver-service cocktail bar, where Ridgway margaritas and Spiga spritzes were shaken up for guests as they mingled their way around the collection. Brunello Cuccinelli did the usual and kept attendees fueled with bowls of its legendary tomato paccheri pasta as they perused the pantsuits on show.

Designers in Paris tend to favour a lighter menu. Glasses of champagne are available at any time of day but the fashion crowd will often be drinking on an empty stomach – or chasing a waiter to grab the last of the miniature caviar canapés. It’s only recently that brands have begun introducing some very welcome dégustation alongside their designs.

By turning industry events into social soirées, Italy’s menswear veterans offer their guests extra motivation to linger and fully absorb the experience and collections. Invitees have the opportunity to get up close to the clothes, watch them being made, pick the brains of designers and network with industry colleagues – all the while savouring the best of Italian cuisine. Clearly, good nourishment is the way to an editor’s heart – contrary to popular belief, fashion editors love to eat – so this is an approach that’s as efficient as it is effective. More fashion week regulars would do well to embrace it.

Of all the big reveals that fashion week has to offer, one of the most hotly anticipated can’t be modelled, worn or bought. Rather, it’s the theatrical sets for Prada’s seasonal shows. Staged inside the Prada Foundation, these backdrops make as much of an impression as the collections themselves. Some of the brand’s most ambitious projects have transformed the space into an abstract paper doll’s house (spring/summer 2023), a metal-clad cage (spring/summer 2024), a supersized office with plants and a trickling stream (autumn/winter 2024) and an intricate scaffolding system (autumn/winter 2025). Talk about thinking outside the box.

The team behind the seasonal transformations is Rotterdam-based architecture practice OMA and its research and design studio, AMO which were founded by by Rem Koolhaas. The fashion world’s go-to for masterminding original runway concepts (it also counts Loewe, Christian Dior and Louis Vuitton as clients), OMA/AMO has been working with Prada on its runway shows since 2004, granting its team a regular audience with co-creative directors Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons.

“The kick-off meeting is a conversation in which we exchange ideas, and Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons describe their ambitions for the upcoming show,” Giulio Margheri, an associate architect at the firm, tells Monocle, granting a rare insight into the Prada process. “The input typically focuses on atmosphere, feelings and directions. It’s more theoretical than visual, though they might sometimes bring specific images, references or fascinations.” From there, Koolhaas, Margheri and their teams translate their input into ideas for the space. “We propose concepts from various sources, which we gradually refine,” he adds. “Both offices like to challenge what can be done. There is restless research in doing new things, exploring and being curious. The functional requirements of the space are always very similar but the process and designs are always different.”

At the label’s most recent spring/summer 2026 menswear show, the runway was devoid of imposing structures and instead featured an open-plan design, complete with retro daisy-shaped shag-pile carpets. “We were trying to do something powerful with minimal intervention,” says Margheri. “This season was about avoiding overly large or complex scenography. Modesty was a key theme throughout the process.”

The set proved to be a blank canvas of sorts for a collection that was equally pared back. “It’s a powerful way to experience space,” he adds. “The show was one of the first times that guests saw the room in its rawness. It was very impactful in its simplicity.”

While forging a situational dialogue, there’s no hard-and-fast rule about the sets speaking directly to the collection, says Margheri, citing the office-cum-meandering creek of autumn/winter 2024 as an example. “The raised floor featured a natural landscape and office chairs. People made assumptions about what the show meant or what it was supposed to be. Sometimes there is an instant reaction to what a set represents. But we don’t see this as something that people need to question or answer.”

Working within the fashion-week calendar’s short timelines makes a successful set installation all the more sweet. Among Margheri and his team’s highlights? Dressing the space in corrugated metal panels, with slime descending from overhead panels. “For that show, we worked with materials not typically used in architecture but scaled them up to architectural dimensions,” he says. “It was one of the first – or maybe the only – times that the set was not fully tested before the show.” In the end, it all worked out, creating yet another powerful memory for the brand’s show guests. “It’s very rewarding to be able to get these things built in such a short time,” says Margheri. “Someone once described this process as a gym for architects – there’s always a need to come up with something new, find new materials and solutions, while working within similar parameters. It forces you to reinvent everything but the core programme itself.”

If you’ve ever strolled through Paris’s public gardens, you may well have stopped to take a seat on its outdoor furniture: green chairs and loungers scattered around fountains and flower beds. Any time the sun comes out, residents and tourists quickly take to the park, where patio furniture is arranged around a table for a group picnic or under a tree for a quiet nap in the shade. On a sunny day it can be difficult to find a free seat – they’re all taken by sunbathers.

Along with the Wallace drinking fountains, the rattan chairs lining café terraces or the iconic dark-green kiosks commissioned by Baron Haussmann in the mid-19th century, the chairs found in Parisian parks and gardens have become a symbol of the city. The sturdy, stylish outdoor furniture, which subliminally transmits a sense of Paris to millions of visitors, comes from a few trusted companies. One of the biggest suppliers is French manufacturer Fermob, whose chairs can be found in the Luxembourg Gardens, as well as on café terraces, squares and the banks of the Seine.

The idea to add lounge chairs to the Luxembourg Gardens was first proposed in 1843 by the French senate, which is housed in the Luxembourg Palace and still owns the green space and its tennis courts. It took until the 1920s for the first collection of chairs, made by the craftspeople at city hall’s Ateliers de la Ville de Paris, to arrive. In the 1990s, Fermob won a competition to produce a modern version and, in 2004, the company called on French designer Frédéric Sofia to redesign the seats in aluminium, making them lighter, more comfortable and easily collected and stacked.

The resulting sage-green “Luxembourg” collection (originally named Sénat) has since become synonymous with the Parisian park. “Our furniture creates a sense of connection,” says Fermob’s chairman, Bernard Reybier. “It’s recognisable and part of daily life and makes people feel that they are in a very Parisian setting. The idea is that you are part of the history of the city.”

Founded in 1890 in Thoissey by a family of blacksmiths, Fermob takes its name from the words fer (“iron”) and mobilier (“furniture”). It remained a small workshop until it was acquired in 1989 by Reybier, who oversaw the growth of the company and expanded its appeal by collaborating with designers such as Pascal Mourgue, Andrée Putman and Matali Crasset. Today the business has expanded greatly but all of its manufacturing still takes place in the Ain region north of Lyon.

Despite its production beyond the city, Fermob’s relationship will always be close with Paris – and it’s continuing to evolve. Last year the firm began furnishing another Parisian landmark, the Champs-Elysées, as part of a project to transform the avenue into a pedestrian-friendly garden by 2030. The Committee for the Champs-Élysées asked Fermob, along with other bistro-furniture manufacturers, to design a new chair for its café and restaurant terraces. “What people like best is a product that has both a good design and a history to go with it,” says Reybier. “The Champs-Élysées is a new story and we will see where it takes us. Maybe it will also become representative of the Parisian identity.”

Click here to enjoy Monocle’s full city guide to Paris

A decade after launching his Tokyo-based brand, Auralee, Kobe-born designer Ryota Iwai is hitting his stride. Auralee has earned a reputation for its masterful use of colour, meticulous tailoring and Japan-made quality. This is elegant, modern luxury – all made to Iwai’s exacting specifications – that is a delight to touch and wear. It’s an alluring mix of Tokyo edge with wearable sophistication, crafted by factories that have been working with Iwai on his journey from the beginning. With stockists around the world and a flagship in the Japanese capital, the label is now attracting global attention. Auralee is also a fixture on the official Paris Fashion Week calendar. Look out for the label’s runway show at the Musée des Archives Nationales at 17.00 London time on 24 June.

Tell us about the new collection.

There is a variety of leather items (including suede and smooth leather), premium wool, and cashmere, along with garment-dyed and garment-washed pieces. The brand’s signature sophisticated heather tones and mustard yellows are part of a colour palette that shifts from the heavy tones of winter to the light, bright hues of summer.

The collection draws its inspiration from the changing of the seasons. Spring brings a mix of cold and warm days. As it gradually gets warmer, it’s always a challenge in the morning to decide on a look, sometimes resulting in outfits that feel like a slightly odd blend of winter and summer. These unexpected pairings can add charm to an elegant look. It is these fleeting moments that inspire the collection.

Any key pieces that define the collection?

Cashmere suits and shirts, hand-sewn coats, silk organdy skirts and dresses.

How does it feel to be returning to Paris on the established calendar?

I always feel nervous and a bit anxious. But having worked on the show for six months, I’m excited about how it will come together.

Is Paris still the best place for you to show?

It is the centre of fashion. Paris Fashion Week is the most global and well-attended event of its kind, so I feel that it is the best place for us.

What are your ambitions for this season? Opening new markets?

Every season, we work with the intention of making the collection better. We also hope that it will reach more people and will be enjoyable to those who see it.

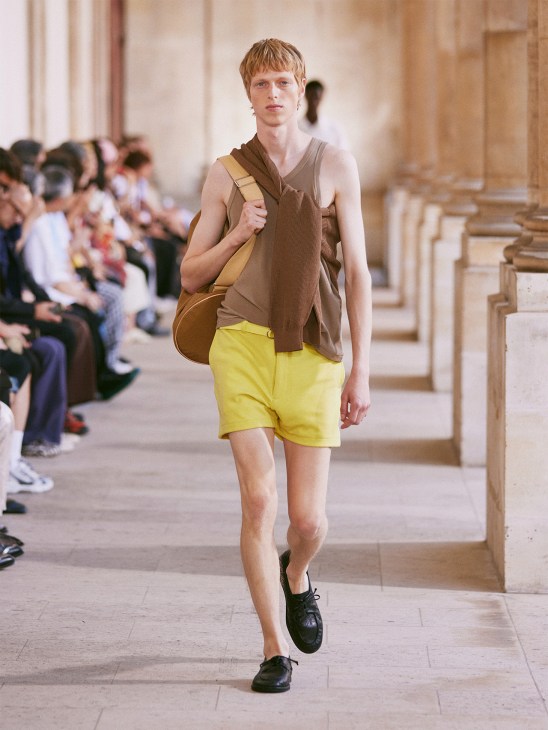

In the internet age, it’s usually easy to pinpoint the origin of a trend. Much was made of Rihanna’s Guo Pei “omelette gown”, worn to the 2015 Met Gala, and the effect that it had on the popularity of the colour yellow. Since then, trend cycles have quickened in tandem with download speeds, to the extent that someone declaring a particular garment the new omelette gown at breakfast might well have egg on their dress come dinner time.

But among all the ephemeral mauves, brattish greens and millennial pinks, one colour has quietly come to dominate the fashion-scape. I am referring, of course, to brown.

Now, like a member of parliament before a debate, I feel I must declare an interest: I am a big fan of brown. Taken out of context those seven words might alarm but one glance at my summer wardrobe should steady your pulse. For in among the tobacco cords and marron moleskins of autumn-winters past are liverish linens and khaki keks. Conversations with my colleagues – a near universally fashion-conscious bunch – reveal a similar predilection for the warm-weather brown. And when anecdotal evidence matches the runways and billboards, a trend’s afoot.

Brown’s appeal is not difficult to discern. It is, as Fiona Ingham, a colour analyst for the House of Colour (a company that helps people find which hues best suit their style and complexion), describes it, both “comforting and nurturing.” Oliver Spencer, a British menswear designer, heralds brown as “dark, rich and beautiful.” Both agree that the colour is well-suited for times when people seek a more casual approach to formalwear. “You can dress it up or down,” says Spencer. “You can buy the suit and wear the trousers on their own, while the jacket looks great with a pair of jeans.” Spencer’s eponymous label even has a “Brown Edit” page on its website. The featured pieces offer two chocolate fingers up at the old adage “no brown in town,” which was used to warn aspirant rakes against mixing brown leather shoes with a dark suit. “This [rule] still remains in the most formally dressed occupations such as law and finance,” says Ingham. “But now, men in many settings feel they can wear [brown] without recrimination.” “It also translates well in knit and cloth,” says Isabel Ettedgui, owner of Mayfair-based clothing brand Connolly, who adds that the colour “has a certain masculine energy.”

But what of the other forces driving the brown wave? Is it part of a wider 1970s throwback or are such mass-participation trends not possible in 2025? Some argue that during times of hardship and uncertainty, people cleave to colours that suit their mood. Could our fractious world help explain a newfound fondness for umber? “No,” says Oliver Spencer. “I think that the exact opposite happens – people bring out bright colours to try to lighten things up.” I suppose that there’s no definitive answer to that question, though a look at the runways would suggest that Spencer is, at least, half-right – the Paris 2025 shows saw the return of yellow and sky blue, alongside the now obligatory 50 shades of brown.

One famous indicator of trending hues is colour specialist Pantone’s Color of the Year. Mocha mousse, an “evocative soft brown” that “nurtures with its suggestion of the delectable quality of cacao, chocolate and coffee” was the company’s choice for 2025.

Whether or not you subscribe to such views, it’s difficult to deny the prescience and influence of Pantone’s annual award. As well as its very effective PR stunt, the US company produces a book called the Pantone View Colour Planner that contains the pigment and textile standards of 64 zeitgeisty colours in nine distinct palettes. The annual publication, which costs around €800, is said to be a must-have for any budding – or well bloomed – clothier, couturier or modiste.

But in the age of Instagram and Pinterest, can there still be top-down progenitors of chromatic trends? Are we still living in a world in which Miranda Priestly, Meryl Streep’s character from The Devil Wears Prada, could so haughtily deliver her “cerulean blue” monologue? “I don’t think so,” says Monocle’s fashion director, Natalie Theodosi. “The runway plays a role but trends now move much faster and are determined by social media, music, films, even current affairs. In some ways it has become the reverse, brands and media follow online trends.” Perhaps therein lies the appeal of brown: it is a fundamentally adaptable colour – both neutral and statement, workaday and fashionable, of its time and timeless – making it perfect for our lives in the permanent now.