Reflect Orbital: The aerospace startup ‘turning on the sun’ at night

The problem with solar panels is that they only work during the daylight hours. But what if you could use satellites to reflect sunbeams down to Earth even at night?

Ben Nowack is obsessed with energy. The 29-year-old Cape Cod-born has explored ideas such as damming the oceans to harness the tides, flattening mountains with gravity batteries and even latching onto the moon with a vast cable. In high school, he says, he built a kind of fusion reactor as a science project.

One of his ideas is now poised to take flight. The CEO of Los Angeles-based start-up Reflect Orbital plans to launch thousands of satellites into space, equipped with mirrors that can reflect sunlight to Earth. By 2030 the company expects to have enough satellites in orbit to provide solar farms with 200 watts of energy per square metre – equivalent to the sun at dawn and dusk – during the evening hours of peak consumer demand. It also hopes to sell illumination to anyone who fancies an extra hit of sunlight, from concert and festival promoters to remote construction sites. “The range of applications for our service encompasses almost anything that an individual can do during daylight hours,” says Nowack.

(almost) on his shoulders

The premise has its sceptics – Youtube astrophysicists relish taking pot shots at Reflect Orbital – but it has also attracted serious interest. The company recently landed $20m (€17.42m) in Series A funding, including investment from Silicon Valley heavy-hitters Sequoia Capital and Lux Capital, and had an audience with Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the crown prince of Dubai, about the project.

There is an emerging global interest in what might become one of the US West Coast’s signature exports within this decade: bold, upstart energy businesses. Big Tech’s embrace of power-hungry artificial intelligence and cloud computing has generated voracious demand for electricity. Now there’s a gold-rush atmosphere among start-ups seeking to innovate clean energy sources, from mini-nuclear reactors to fusion power.

But Reflect Orbital is looking for ways to better harness humanity’s oldest source of energy. When Monocle visits the company’s lab in Hawthorne, a small city in Los Angeles County that’s home to a slew of aerospace start-ups, Nowack and his CTO, Tristan Semmelhack, are eager to show off their progress since founding the business in 2021. (First, however, your correspondent must show proof of US citizenship and agree not to photograph certain aspects of the satellite-making process in order to comply with laws around technology with national-security implications.)

As early as next spring, the company will launch a 100kg satellite packed into a box the size of a microwave. In space, the satellite will unfurl four triangular panels creating an 18-by-18-metre surface mounted to booms, attached like sails on a ship’s mast and position itself in orbit along the line separating daytime from night-time on Earth. Nowack and Semmelhack say that the system is reactive, allowing for precision angle changes within seconds as the Earth rotates. While this first satellite can only generate about four minutes of daylight over a 5km radius, the founders say that a ring of 18 satellites trained on the same location could illuminate one spot for an hour.

The technology sounds like sci-fi but it has precedents. In 1993, Russian satellite Znamya cast a 5km-wide beam the strength of a full moon onto a narrow stretch of Europe for a few hours. In April 2024, Nasa launched the ACS3, a spacecraft that successfully unfurled a solar sail, which reflected sunlight to generate propulsion.

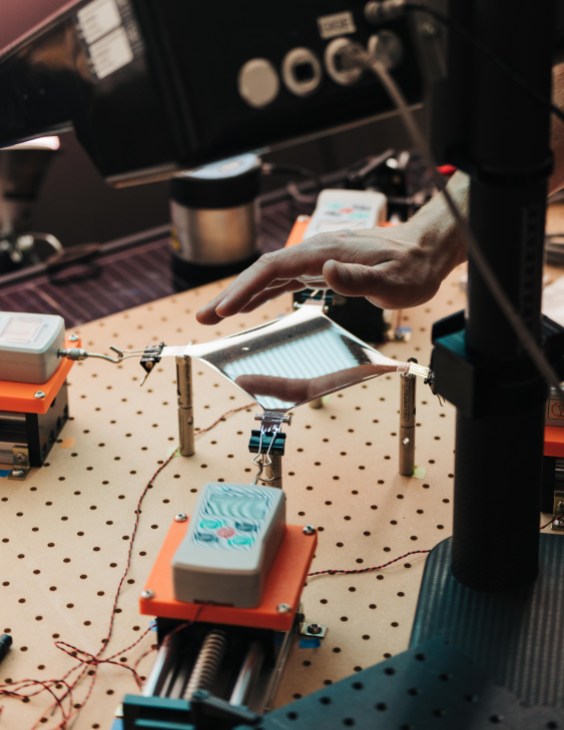

The key difference between Reflect Orbital and its space-agency predecessors is that the team wants to turn a profit. The company’s 22-person crew, expected to grow fast this year ahead of the first launch, builds its own components and does much of the fabrication itself on a lean budget. The prototyping workshop is a tinkerer’s paradise of Milwaukee tools, Fiskars rotary blades and Scotch tape, and a sample reflecting sail is laid out in a brand-new “clean room”. Semmelhack, a laid-back New Yorker climber with shaggy blond hair and wearing a flannel shirt, brings out a palm-sized scrap of the ultra-thin sail material and lets it float in the air like a plastic bag.

Reflect Orbital’s do-it-yourself spirit is also evident in its car park, where the team shows off a homemade, 13-metre-long oven in which carbon fibres can be baked into booms. These coil like a tape measure, keep the reflective sail taut and weigh almost nothing.

Building the oven cost a mere $40,000 (€34,000) and took the team a month. “If we were Nasa, this would be a million-dollar device – and the project wouldn’t make any money,” says Semmelhack. “We don’t have a huge amount of capital or time, so we have to build stuff quickly and cheaply that works well enough for our purposes.”

One block away is SpaceX’s original headquarters and the tip of its first successfully recovered Falcon 9 booster can be seen peeking out from among the warehouses. Elon Musk moved SpaceX from California to Texas in 2024 but talent remains clustered in Hawthorne. “It’s very easy to get things built with machinists around every corner,” says Nowack. “If you need the perfect laser weld, the guy who did it for the SpaceX and Nasa missions is here.”

Nowack interned at the pioneering commercial space company and its monument, put on permanent display by Musk in 2016, is a visible reminder that proof of concept is vital in this industry if you want to be taken seriously. The clock is ticking on Reflect Orbital’s deadline to load up a rocket and deploy its first sail in the spring of 2026. Yet the commercial space industry has become astoundingly cheap by satellite-launching standards – just $6,500 (€5,500) per kilogramme, or eight times cheaper than it was on Nasa’s now-retired space shuttles – and this is presenting an opportunity for space start-ups such as Reflect Orbital that want to get their projects off the ground.

In order to deploy 100 satellites per rocket launch and reap what it believes could be billions of dollars in revenue, the company is banking on the cost of joining such launches continuing to decline. It is currently fine-tuning its design in a bid to get its satellite-production costs down from $2m (€1.7m) to less than $100,000 (€85,000) per unit.

Where that revenue will come from is still uncertain. But Reflect Orbital has its theories: municipalities seeking to save on street lighting, those engaged in search-and-rescue operations, construction firms operating in remote areas that want to extend the working day – and even Arctic villages hoping to make winters more bearable (bringing light to Russia’s Far North was one of Znamya’s goals).

Objections to the technology aren’t hard to imagine, not least the light pollution and its potential to disrupt the rhythms of flora and fauna. Never mind the complaints from neighbours who don’t want dawn and dusk extended. The company has had preliminary conversations with environmental groups concerned with the matter but the founders say that the light will be dispersed rather than a harsh spotlight and the technology will allow them to quickly point the satellites elsewhere. “Give us four minutes,” says Semmelhack. “If everyone hates it, we can turn it off.”

That might sound like a shaky business plan but there are more remote deployments of Reflect Orbital’s technology that make sense. Semmelhack imagines lighting up a pasture at the behest of a rancher or a ceremony for a sheikh. “We have the benefit of [working across] large areas of land that are controlled by very few people.”

Reflect Orbital started taking applications for its service last autumn and, according to the company, was flooded with 164,000 requests from 157 countries. The company is planning a 10-location “world tour” once the first satellites are aloft, imagining the kind of mass gatherings that a solar eclipse can attract. Sunlight on demand is a large-scale parlour trick that will generate hype. But what drives Reflect Orbital’s mission is the energy business and making the most out of solar panels, says its chief strategy officer, Ally Stone. “It’s a way to unlock value from an already financed, already operating solar asset.”

Reflect Orbital is one of many West Coast enterprises exploring new power-generation schemes as Big Tech pledges to stay true to its commitments to net-zero emissions. For years, data centres have been popping up along the hydropower-rich Columbia River Basin. But the current grid network is insufficient, says Julia DeWahl, a Los Angeles-based angel investor and co-founder of microreactor start-up Antares. “Forecasted energy demand is a step-function increase in growth largely driven by AI,” she says.

Every AI-powered Google search uses 10 times the energy of a traditional search. In response, its parent company Alphabet, alongside Amazon and Meta, have pledged to support efforts to triple nuclear-power production by 2050. Microsoft is resurrecting Three Mile Island, a Pennsylvania nuclear plant infamous for a 1979 meltdown. Meanwhile, there are entrepreneurs across North America working on small scalable nuclear reactors, such as the Bill Gates-backed Terrapower, which plans to be running in Wyoming by 2030. Elsewhere, in the Seattle area, start-up Helion is working on the world’s first fusion-power plant.

“After so many years of software start-ups, there’s a boom around building real things,” says DeWahl. The location of many of these companies is no accident. “There has always been so much innovation on the West Coast.”

Not every idea taken from a sci-fi novel will work but there’s smart money betting that Reflect Orbital can pull it off – with the potential for a considerable return on investment too. The founders expect public support for their solar spotlight, even if that might partly be tech-bro swagger. “If you zoom out and look at this with a bit of perspective,” says Semmelhack, “this is just so cool.”