At Intertabac, Big Tobacco is rebranding for a future without cigarettes

Clearing the air at Intertabac in Dortmund, where the tobacco industry’s nicotine high priests discuss a ‘smoke-free future’. What’s rising from the ashes of this condemned industry?

Every September the Westfalenhallen conference venue – known for darts tournaments and dog shows – is transformed into Intertabac, the world’s largest tobacco fair. It is billed as a “global meeting place of the industry” – a space to clear the air over how the market worth more than €1trn annually is plotted, priced and branded for acceptability over the year ahead.

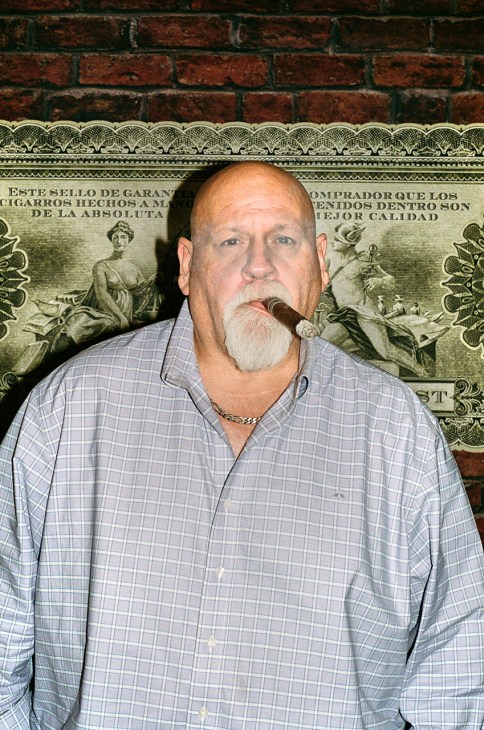

The crowd is a curious mix: cigar purists in linen jackets, vape bros in streetwear and a small army of tight-lipped lobbyists huddled in side rooms over Powerpoint decks on FDA rulings and EU directives, muttering about the possibility of a UN plastics treaty.

It’s a strange and sometimes unsettling scene when you consider the proven ill effects of much of what is sold here (and the questions around what is yet to be proven). Cohiba cigars from Cuba are displayed as if they are objets d’art, start-ups peddle candy-flavoured vape juice from neon booths (Grandma’s Apple Pie, anyone?) and nicotine pouches are branded like wellness products. But something is strangely absent: the condemned ancestor to the smoking industry – cigarettes.

The nicotine market is undergoing its biggest rethink in decades. At British American Tobacco, the manufacturer of Pall Mall and Lucky Strike, an aspirational banner unironically declares “Building a smokeless world”. The company unveils an e-cigarette with an app that tracks every puff and allows users to fine-tune their vapour clouds with a feature cheerfully called Cloudcontrol. “You can even set a limit for when it stops,” says representative Joshua Bakker, pitching self-quantifying nicotine intake with the breeziness of a clued-up personal trainer.

Next door, Philip Morris International (PMI) is showing off the newest iteration of its Iqos tobacco-heating device, now with a touchscreen and a pause mode that is “perfect for when the pizza guy arrives,” says spokeswoman Beate Kunz. The company has poured some $14bn (€11.96bn) into the development of such products over the past two decades, part of an ambition to become more than two-thirds “smoke-free” by 2030. For now, the research effort is still largely bankrolled by Marlboro sales. Iqos, Kunz says, is designed to be about 95 per cent less harmful than traditional cigarettes because it heats tobacco rather than burning it. PMI, however, has no plans to end the sale of cigarettes. “Pulling the plug overnight would just tank our business while competitors keep selling – we wouldn’t have ‘saved’ a single smoker,” she adds.

A smoke-free future is marketed as a moral project but it’s also a business plan. The gadgets on display at the fair are proof of strategy. With cigarette sales shrinking across major markets due to higher taxes and growing stigma, Big Tobacco has found in vapes and heated-tobacco devices not only fresh profits but a new narrative to cast itself as part of the solution rather than the problem. Its fiercest rival isn’t other tobacco brands but Elfbar, the Chinese vaping powerhouse. Its candy-coloured, highlighter-like devices are banned in its home market but in Europe, the company is doubling down with even more flavour blends planned for next year, its distributor tells Monocle.

Some countries, including the Netherlands, have already banned flavoured liquids – a move that Philip Drögemüller, head of the German lobbying group Alliance for Tobacco-Free Enjoyment, calls a serious mistake. “Flavours are what get adult smokers to switch in the first place and banning them just fuels the illegal market,” he says. It’s a persuasive point, though one that conveniently ignores the reality that the same fruit and candy flavours are what make vaping so appealing to teenagers. Drögemüller cites his own success story. “I quit smoking after 20 years because of vaping. Fruit liquids made me lose the craving for tobacco completely. There really is no good political reason not to support it.”

Behind the glossy booths, side rooms hum with strategy sessions where lobbyists and executives plot their next moves. Panels with titles such as “Switching evidence on trial” and “Navigating the EU tobacco product directive” parse rulings, court cases and the next rounds regulation. There is talk of whether filters could be banned entirely under new environmental rules, what the UN plastics treaty might mean for cigarette butts and how to keep flavoured products in circulation despite looming restrictions. It feels a bit like a crisis summit where the industry quietly co-ordinates its survival strategy, trying to stay one step ahead of regulators.

The fight is no longer just about profits but about legitimacy and the industry’s right to remain a serious voice in policy debates even as its core product faces mounting political and social pressure. At the fair’s opening press conference, associations struck a combative tone, warning that planned tax hikes would push smokers to the black market, drain state coffers and wipe out mid-sized manufacturers. Germany, for example, is preparing to align with new EU rules by raising its comparatively low cigar tax by as much as 1,000 per cent. “That is nothing short of a war of annihilation by the EU Commission against our industry,” says Bodo Mehrlein of the German Cigar Manufacturers Association.

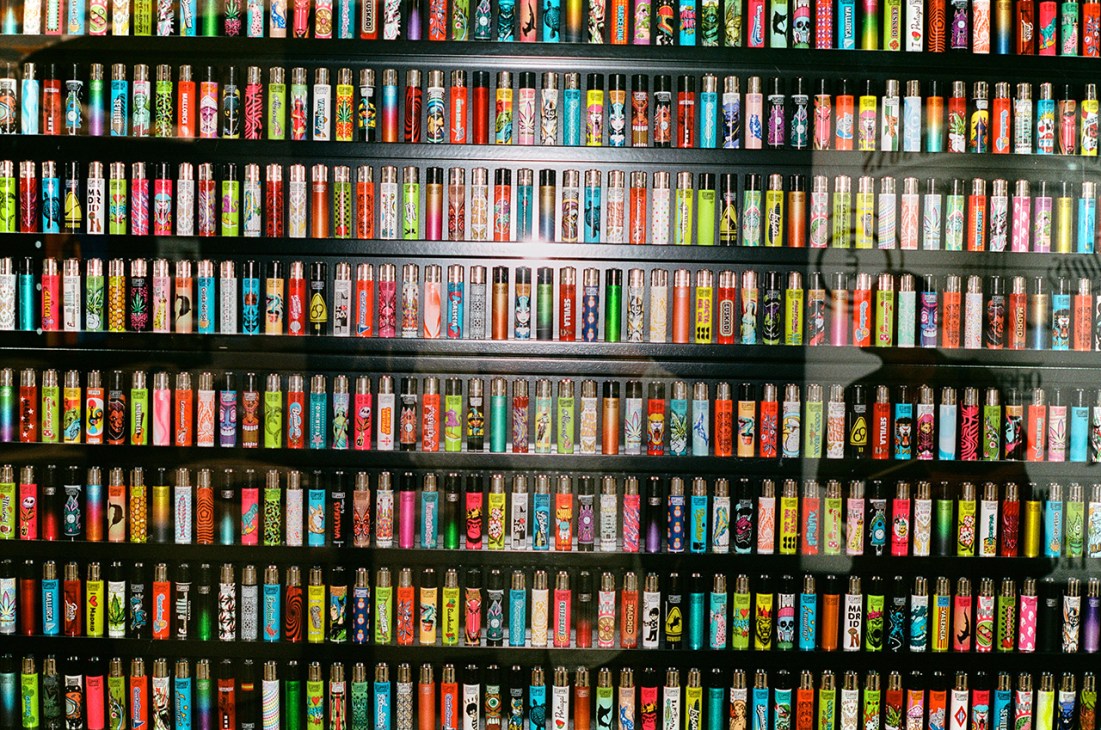

The shift is rippling through the entire smoking ecosystem. Zippo, the lighter brand that kept generations of GIs and rockabilly kids flicking, now offers a vape insert that slips neatly into any classic case. OCB, best known for its rolling papers, is reorienting toward cannabis smokers, partly because roll-your-own tobacco faces a steep tax hike. Even Nuremberg-based heritage pipe maker Vauen reports that its Lord of the Rings-style churchwardens (the very kind used in the films) are now its most popular line, beloved by cannabis smokers for the same reason hobbits prized them: you can sit back and puff in peace.

There are hi-tech twists on old rituals too. Air, calling itself the “global leader in social inhalation”, presents a coal-free shisha device: Nespresso-style capsules slot in and an NFC chip adjusts the heat profile to the chosen flavour for a perfectly calibrated draw. Nearby, Dr Karsten Behlke unveils what he calls the first true pocket-sized shisha. “Our development actually comes from medicine,” says the lawyer-turned-entrepreneur. “It’s a genuine shisha that uses real tobacco – no vape liquid like the fake ones.” Rather than burning the tobacco, the device heats an air stream, cutting out many of the harmful by-products still present in vapes and water pipes. “But the main selling point is really the size. Most shisha smokers aren’t exactly worried about their health,” says Behlke.

The newest star of the so-called “reduced-risk” market is the nicotine pouch – banned in some countries, barely regulated in others and a clear darling of this year’s fair. “The market is exploding,” says a Chinese manufacturer of pouch-making machines. “In Europe, you currently have to wait a year for a new machine. We can deliver it in two months.” Exhibitors tout faster nicotine hits with lower doses that “bring flavours to life and improve mouthfeel” while others present “pouches designed with your mouth in mind”. Panels promise insights into “smooth, satisfying nicotine delivery over 45 minutes” and strategies for “where the oral nicotine market is headed – and how to stay ahead of the curve”.

With cigarettes barely visible on the show floor, you might think the coffin lid has been nailed shut – but not quite. Esse, a super-slim cigarette brand from South Korea that has sold nearly a trillion sticks since its 1996 debut, has just expanded to Germany. “Demand is on the rise,” says Christopher Lim of Korean tobacco giant KT&G Corporation, the label’s producer. At the fair’s own Intertabac Stars award show, it was crowned cigarette of the year. “Cigarettes still command a considerable market share, especially outside Europe,” says Atanas Doychinov of KT International, the Bulgarian outfit born from the state tobacco monopoly. Akin to other manufacturers who will only say so off-record, KT International is looking toward rapidly growing markets in Africa and Asia-Pacific. “We’ll see a big increase in these developing markets throughout the next few years,” adds Doychinov. Why no vapes? “For us, as an independent company, it’s too risky to put large investments in a market that is still fairly unregulated,” he says. “We‘ll wait until things are sorted out.” The “smoke-free future”, it turns out, might still be a long way off.

Clearing the air

With more than 800 exhibitors from 70 countries, Intertabac bills itself as the world’s largest trade fair for all things tobacco – from cigars and rolling papers to vapes and new gadgets. This year, though, the headlines weren’t only about product launches: port authorities uncovered a record number of tax violations. According to Dortmund’s customs office, 22 exhibitors were caught with untaxed goods – a sharp rise from just five in 2019. “In one hall we charged everyone,” a spokesperson says, noting that seizures included cigarettes, rolling tobacco, e-cigarettes and liquids. Criminal proceedings have been opened for tax evasion and approximately €59,000 in security deposits were collected on the spot.