Want to make lasting memories? Here’s why you should keep your phone in your pocket

Technology has amplified our impulse to photograph everything. But what if we didn’t view the world through our phone screens?

Why do we feel the compulsion to photograph or film everything that we deem important? Technology has amplified this impulse but what if we didn’t view the world through our phone screens? Studies suggest that keeping them in our pockets is a more considered way of making memories.

Maybe Kate Moss had drunk a little too much. Perhaps her high-heeled shoes got tangled up in the deep-pile carpet. In any case, the way that she walked into the Ritz in Paris one evening in autumn 2024 was less elegant than usual. Not that many were there to pass judgement. One keen observer, however, recorded the scene and posted the video on social media, giving it the title “The moment Kate Moss comes back totally drunk from a fashion show”.

There are a lot of such “moments” out there on Youtube, Tiktok and Instagram. But videos in the same style are also being shared every day in the tabloid media: the moment when a car falls off a bridge, the floodwaters rush into Valencia or a spoilt child destroys half of a Walmart supermarket.

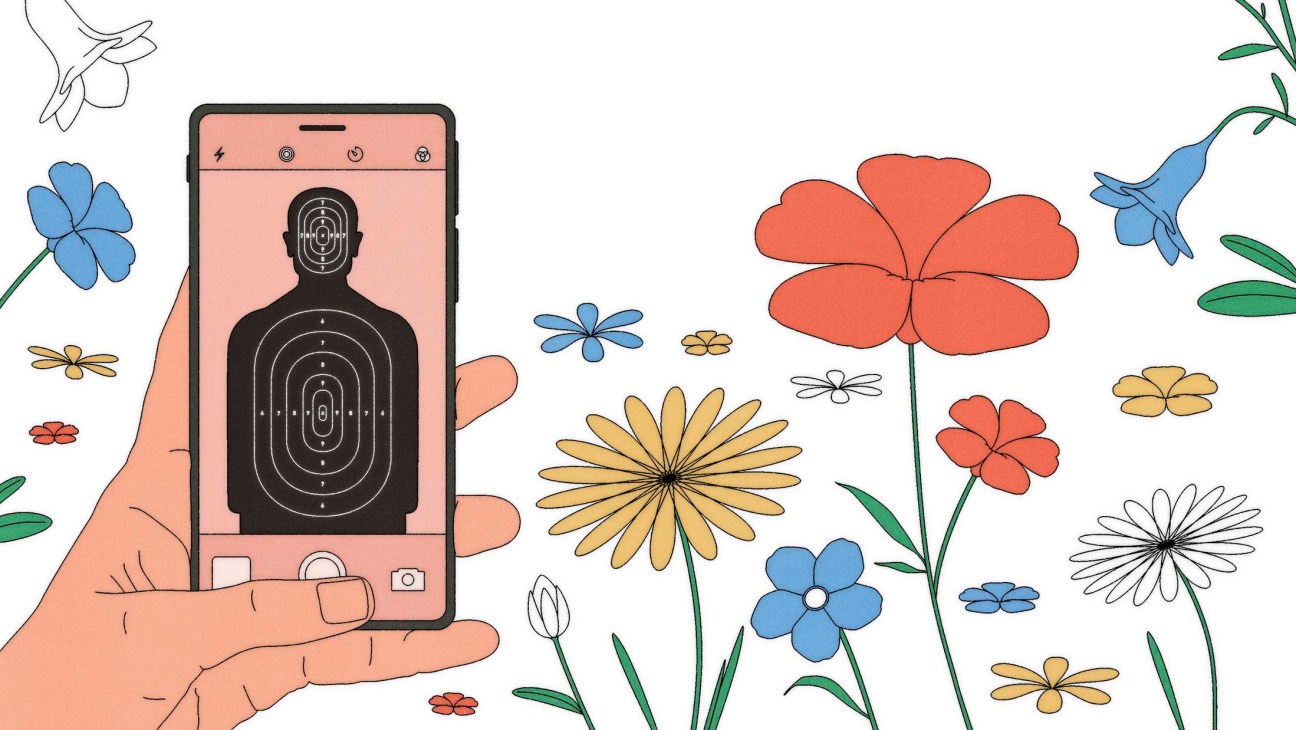

What tends to get a little lost in discussions about all of this is why there are so many of these photos and videos in the first place. Is it simply that people were filming when something happened? Or perhaps it’s that modern, hyperactive phone users pull out their phones as soon as something exciting or unusual takes place. Like cowboys of the past who always had their gun at the ready, they instinctively pick up their device and pull the trigger, many at only the slightest provocation. Even the movement from the hip is similar: men quickly reach into their trouser pockets while women often carry their smartphones on a chain on their side like a holster so that they always have it close to hand.

More than 95 million images and videos are uploaded to Instagram every day. The number of images that never see the light of day but are taken for private purposes is likely to run into billions. Check how many you have in your own photo gallery: it is not uncommon for the total to be in the mid-five figures. Dozens of blurry concert shots, hundreds of incredibly exciting scenes from the school football match, countless pictures of food on plates – which of these would have made it into a physical photo album of the past?

One could argue that people are trying to capture the fleeting nature of life, for themselves, for their contemporaries and for posterity. After all, didn’t even our ancestors in the Stone Age leave hunting scenes scrawled on rock faces? Perhaps the impulse to capture moments has always been there. And every new medium, from drawing and writing to photography and film, has dramatically increased this tendency. In the 1980s technology-loving parents seemed to be constantly on their children’s heels with a camcorder. With the smartphone, everyone now has the ultimate recording tool in their hands.

“Every picture not taken is a moment spent being present”

Some children must have the same strange experience in their first years of life as pop stars do at concerts: they are constantly looking into a sea of camera lenses, as if the smartphone were some kind of front-end visual apparatus. If this sight had been staged in a science-fiction film 50 years ago, people would have probably shaken their heads at how stupid it looks.

If you ask anthropologists about the origin of the revolver-like “cell-phone reflex”, they will tell you that it’s less about a love of documenting things than about the human urge to “locate oneself”. At least that’s how Nicholas J Conard from the University of Tübingen puts it. “People used to carve their initials or the words ‘I was here’ into trees and park benches,” he says. “Today they take a selfie.” It’s a bit like dogs marking their territory.

In the past, postcards were used not only to send greetings, missives about the temperatures and culinary discoveries to those at home but also to call out to them, “Look where we are!” Tour guides report that nowadays younger tourists “shoot” sights with their cameras and then immediately want to move on.

In everyday life digital pins are placed and photographs are taken, as though people want to constantly reassure themselves of their own existence and, of course, excellence. The sexy, sleepy look in the mirror in the morning, the first coffee, the outfit of the day, the menu when going out – if it isn’t recorded, did it even happen?

In 2012, The Atlantic magazine published an article headlined “The Facebook Eye”. The author warned that the digital reward system of attention and likes meant that we were in danger of only focusing on potential posts. As a result, our brains would automatically check everything we experienced to see if it could be used.

Thirteen years and a few platforms later, this fear has not only been proven to have been well founded but the phenomenon has also exceeded our wildest expectations. There are influencers who stage and monetise their lives. But everyone else who posts something on social networks has also become a sort of entrepreneur, flogging mundane elements of their everyday lives, which they serve up to the attention economy. Those who experience the best, funniest, craziest things get the most approval. You just have to press the shutter at the right moment.

“The more we try to capture a moment, the more fleeting it becomes”

The shooting frenzy has a certain added value. While in the past there was hardly any direct documentation of exceptional events, today photos and videos almost always appear. In the attack at Ariana Grande’s 2017 concert in Manchester, the police were able to reconstruct the course of events primarily based on private recordings. If, in May 2020, 17-year-old passer-by Darnella Frazier had not filmed how a police officer blocked George Floyd’s airway with his knee as he lay on the ground, the perpetrator would probably never have been convicted. Conversely, hordes of such amateur reporters are increasingly blocking access for rescue workers at crime scenes. The first instinct is no longer to help but to pull out your mobile phone.

It’s not the person who isn’t filming who is missing out on anything. On the contrary: studies suggest that it’s harder to remember special moments in your life if you’re taking photos or making videos while you’re doing it. And not just because you’re less attentive but because your brain knows that you could watch it all again later. That’s why it doesn’t really “store” these moments in the first place. Researchers at Yale University also came to the conclusion that, to a certain extent, holding a screen in front of you emotionally disconnects you from what you’re seeing and the moment is experienced much less intensely. Instead of being the protagonist of your own life, you become a disinterested observer. No amount of recording, no matter how good, can change that later on and you’ll probably never watch most of it anyway.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, German philosopher Walter Benjamin put forward the thesis that an object loses its aura when it is no longer experienced directly in its original context. The same argument can be applied to personal experiences: the fashion show doesn’t feel nearly as glamorous on video. The crocodile that suddenly swam through the river in Australia doesn’t send a shiver down your spine afterwards. The child’s amazement at its first steps can be watched a hundred times but never experienced in the same way again.

The more that we try to capture a moment the more fleeting it becomes. All recordings of it seem empty. Not to mention the time that goes into it. You don’t just take one picture but several. Then you edit, process and publish it.

Because modern smartphone users love taking part in challenges that they are then asked to record and share via video, here is a challenge for the coming weeks. Let’s call it “Let it go!” It’s about not posting anything, not recording anything or taking photos – just watching the children’s sledding race, enjoying a meal with your loved ones phone-free and not singing along to your favourite band’s performance while clutching your device.

Let’s be honest: nobody is really interested in other people’s concert clips. Even “likes” for plates of oysters or cheese fondue videos are at best friendly handouts. Every picture not taken is a moment spent being present. In return, it might stay on that other, human hard drive for a little longer.

About the writer:

Wichert is a journalist and fashion writer at the Süddeutsche Zeitung. A version of this article was first published in German in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.