Following specialist investigators on the hunt for Nazi-looted works of art

After the recent Louvre heist, a reminder that the world’s missing art is rarely gone for good – just waiting to resurface, often in the most unexpected of places.

When Dutch journalist Peter Schouten rang the doorbell of a house in Mar del Plata in early August, he didn’t know that it would unleash a global media storm. Schouten had travelled to the Argentinian city at the behest of a colleague, Cyril Rosman. For a decade, Rosman had been on the trail of a trove of missing artworks; the story of which reads like a thriller, with an intriguing cast of characters and a plot that spans geographies and generations. Rosman’s investigations centred on the family of Friedrich Kadgien, a financial adviser to Nazi politician Hermann Göring, who escaped to South America after the Second World War. Rosman had long suspected that Kadgien’s two daughters, Patricia and Alicia, might have knowledge of artworks looted during the Nazi regime from Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker. The latter’s heir, Marei von Saher, is in her eighties and lives in New York; she has spent much of her life searching for her father-in-law’s collection.

The first recorded art theft took place in the 15th century, when Polish pirates boarded a ship bound for Florence and absconded with the Hans Memling painting (above) “The Last Judgement” (1467-71). The artwork currently resides in the National Museum of Gdánsk, much to the chagrin of some Italians. (Image: Stephen Barnes/Alamy)

A dog barked inside the house but no one answered the door to Schouten. As he waited, he noticed a “For sale” sign and took a photo on his phone. Later, while having dinner at his hotel, he found the listing for the property online and spotted an image of a gilt-framed painting hanging above a green velvet sofa. He sent the link to Rosman in the Netherlands, who, the next morning, replied with excitement that he was reasonably confident that the artwork was the 1710 painting “Portrait of a Lady”. Over the next couple of weeks, Schouten was able to confirm that the painting was still in the house and tried to contact Patricia Kadgien through multiple channels. He received some ambiguous replies before being blocked on social media. Schouten’s story about the discovery was published on the Dutch news site Algemeen Dagblad (AD) on 25 August. “And then the rollercoaster started,” he says.

Along with the world’s media, multiple law enforcement agencies – Interpol, the FBI and the Argentinian police – quickly became involved. But when officers raided the Kadgien house and four other properties a few days later, the painting seemed to have vanished. The artwork’s second disappearance did nothing to quell the interest and the local general attorney assigned 15 people to work on the case. Eventually, the collective pressure of the media and the police yielded a response from the Kadgiens. On 3 September, the family handed over the painting and it was put on view at a media conference.

A criminal investigation has since been opened, which will focus on Patricia and her husband, and whether they attempted to obstruct justice by hiding the painting. “Portrait of a Lady”, meanwhile, will most likely make its way to New York and to Marei von Saher. “To dedicate your life to getting back all of your family’s possessions must be unbelievably tough,” says Schouten today, who was in regular contact with Von Saher throughout the saga. But he wishes that he could have spoken to the Kadgien sisters and heard their side of the story. “I can’t imagine what it’s like to have a father like that,” he says. “You are not to blame for your parents’ behaviour but you carry it with you your whole life.”

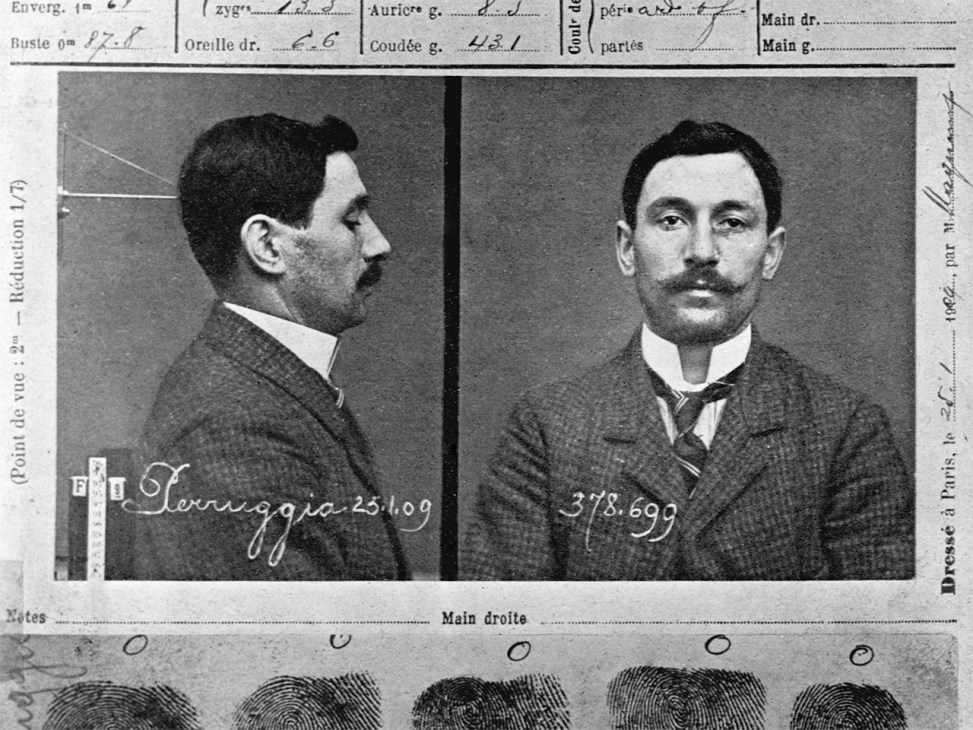

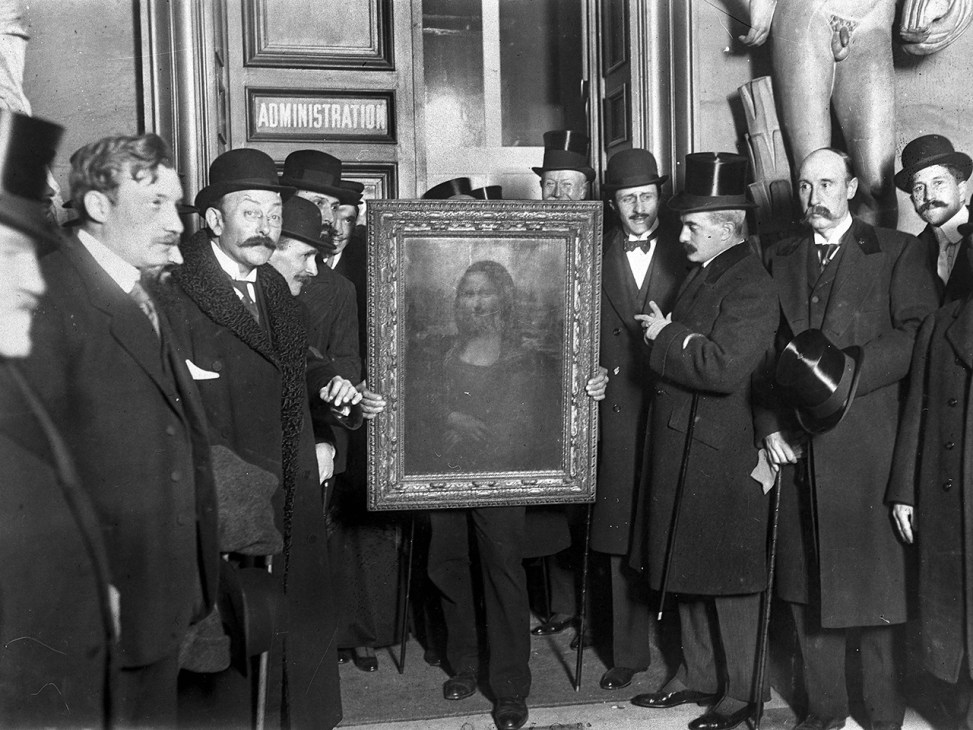

There was far less fuss about Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” before it was stolen from the Louvre by a thief dressed as a museum employee in 1911. Parisians flocked to see the empty space where it once hung. The thief and the painting were eventually found in 1913 when he tried to sell the work. (Images: Getty Images)

The Nazis are thought to have looted about 20 per cent of Europe’s art between 1933 and 1945, much of which – at least 100,000 objects – has yet to be returned. Of course, their regime was just one perpetrator of art theft. Schouten’s story made headlines across the globe but the everyday work of hunting for (and occasionally finding) lost or stolen artworks usually takes place with less fanfare.

On a quiet lane in central London is the unassuming office of the Art Loss Register (ALR), an organisation with the world’s largest private database of stolen art, antiques and collectables. Unlike Rosman’s quest to locate artworks from Goudstikker’s collection, the ALR checks individual items entering the market to investigate their provenance and demonstrate due diligence. The register currently features more than 700,000 lost or stolen artworks and the ALR performs about 450,000 searches on items prior to their sale. These are carried out on behalf of the likes of governments, law enforcement, museums, auction houses or private individuals.

“What we are looking for is some proof that the item can be sold on the open market,” says Olivia Whitting, the ALR’s head of cultural heritage and client manager. The organisation also registers the theft or loss of items and helps to reunite some of them with their owners. “It’s quite exciting because it’s the kind of detective work where you end up knowing so much about random parts of history, such as the great telephone exchange of the year 2000,” says Whitting. “That was when London phone numbers went from starting with ‘0171’ or ‘0181’ to ‘020’. If a document is from before 2000 but it has the newer telephone code, you might question whether it’s real.”

Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of art was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990. The robbery is believed to be the world’s largest art heist and remains unsolved. (Image: Ryan McBride/AFP via Getty Images)

The work of registering objects on the database – or trying to match items to them – is usually done digitally. But when Monocle visits in early autumn, among the desktop computers, coffee mugs and copies of the Antiques Trade Gazette is an extraordinary artefact. In the corner of a room, under a blanket, is a 14th-century cenotaph. The grave marker was handed over to the ALR for restitution by an antiques dealer who had been tipped off that it was probably stolen. The ALR is now researching its origin to enable its return. The organisation has ascertained that it is probably from the late-medieval Timurid empire and from the grave of a young man or a child. The next step will be to approach the relevant embassy and investigate whether it can be returned to its country of origin.

When something is registered as lost on the database, the ALR will ask for proof of loss (such as a crime reference number) and of ownership. This might be an acquisition invoice or insurance document but it could also be a family photo featuring the artwork. Whitting was recently sent an image of a three-year-old girl having a tantrum on the floor in front of a Palmyrene sculpture and another picture of a Roman bust dressed in a tinsel crown at Christmas. “It’s a window into someone else’s childhood,” she says.

The ALR database of missing artworks reflects the breadth and strangeness of the wider market. It includes a toy car (an Aston Martin replica), JMW Turner’s death mask and a set of George Washington’s false teeth. “When human remains come up, that’s often when we think, ‘I wish this wasn’t on the art market,’” says Whitting. She recounts how a Belgian zoo recently wanted to look up a human head that had somehow, years ago, ended up in its collection. The ALR refused to search it and advised the zoo to try to return it to the Polynesian island from which it originally came.

French thief Stéphane Breitwieser stole more than 200 works by the likes of Jean-Antoine Watteau from 172 European museums. When he was arrested, his mother destroyed most of the pieces to hide the evidence. (Image: Christian Lutz/AP via Alamy)

Items on the register – paintings, vases or the occasional body part – might have been taken in a burglary or looted as the spoils of war. In the estimation of James Ratcliffe, the director of recoveries at the ALR, about a quarter of the database consists of works that were lost during the Second World War. “That doesn’t even touch the sides of what was taken by the Nazis,” he says.

Others are looking for these objects too. In Magdeburg, the German Lost Art Foundation acts as the country’s central body overseeing looted cultural property. It oversees hundreds of projects exploring Nazi looted art and manages its own register, the Lost Art Database. “We always have to keep in mind that we’re not only talking about the works of Pissarro, Picasso and Cézanne,” says Andrea Baresel-Brand, the head of the documentation and research data-management department. “We’re also talking about everyday things: knives, forks, cups and plates. For a family, they could mean everything.”

The story of looted art is tied to history but shaped by the present. In Germany, that often means contending with right-wing political parties that, says Baresel-Brand, “prefer not to deal with the past”. Elsewhere, attitudes in the art market have changed when it comes to dealing with items from colonised countries. “It’s interesting to think about the new frontiers of repatriation and the moral side of acquisitions,” says Ratcliffe. “Ten years ago the colonial history of an object was a curiosity. Now there’s a recognition that it’s an issue that needs to be addressed.” It’s a complex environment and Ratcliffe believes that the art market is sometimes a scapegoat for bigger questions facing society. “We’re calling this decolonisation but it’s not,” he says.

Gustav Klimt’s dazzling “Adele Bloch- Bauer I”, stolen by the Nazis from Jewish industrialist Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, hung for years in Vienna’s Galerie Belvedere. It was returned to Bloch-Bauer’s heir in 2006. (Image: Herbert Pfarrhofer/EPA via Shutterstock)

The field of looking for lost artworks is changing in other ways too. There has been a move towards “positive registration”, with the cataloguing of artefacts in museums that might be in danger because they are in a region at risk of conflict. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence is expected to improve the image-matching process but it will take longer for it to perform the intricate work of due diligence. It’s also likely that technology will be used to create fraudulent documentation. “Say you have an export licence for a Roman mosaic from Lebanon in the 1970s,” says Ratcliffe. “Suddenly it’s possible for that document to appear with another mosaic. Tech will help people fighting against art crime but will also help those committing it.”

Combining the knowledge of an art historian with the nous of a detective, solving art crime is a complicated business. From the ALR’s database of artworks, three to five matches a week are made, while another department – the organisation’s busiest – looks into stolen watches and logs about 15 matches a day. Meanwhile, finding a “just and fair solution” to the question of what to do with a found stolen object is often not a straightforward process. Legal technicalities clash with the beliefs of individuals and, sometimes, the history of entire nations. As Schouten has discovered, the simple act of ringing someone’s doorbell can have sweeping consequences. It seems that the past, with all its painful memories and unresolved questions, is closer than we think.