Comic relief: The artisans keeping the art of manga-making alive

Digital printing has stripped the craft from Japanese manga. Meet the typesetters staging a print revolution.

You might not have noticed the revolution that’s occurred in the world of Japanese manga in the past 15 years – unless you were looking closely. The comic-book art form that traces its roots back to the witty, whimsical images of the great Ukiyo-e woodblock print artists, has moved squarely into the digital world. Manga, once available only on paper, is moving unstoppably from print to mobile phones and tablets. Not only that but the manga that are still printed on paper have undergone their own technical transformation. In the blink of an eye, an army of skilled typesetters – the people who put the words into manga – has been replaced by digital technology.

There’s no need to worry about the industry itself; the numbers are still huge. Manga sales generated a staggering ¥704.3bn (€4.3bn) in 2024 – the first time they had topped ¥700bn and up 1.5 per cent on the previous year. This accounted for 44.8 per cent of Japan’s entire publishing market. But to understand how the industry is changing, you need to dig into those numbers. Digital manga sales have nearly doubled since 2019, last year totalling ¥512.2bn (€3.2bn) or 72.7 per cent of the market, while sales of physical comic books and magazines dropped 8.6 per cent over the same 12-month period, coming in at ¥192.1bn (€1.17bn). Manga lovers are still eager to get their weekly fix but it’s more likely to be downloaded onto a device than read in the chunky paper comics that are sold in convenience stores and bookshops.

One person closely following this shift has been Masashi Kinpachi Okamoto, who has worked for Shueisha, one of Japan’s most renowned manga publishers, since 1994. Shueisha has many hit titles, none more so than the juggernaut One Piece, which has sold 500 million volumes since it came out in 1997. It is the best-selling manga by a single author. As he was overseeing the transition to digital production and the creation of Shueisha’s vast digital archive, Okamoto realised that the move away from paper was closing the chapter not only on the printed product itself but on the skills required to make it. Even the artists have gone digital. “The number of manga artists who still draw on paper with pens has become increasingly rare,” says Okamoto. Like any true fan, he wanted to preserve those techniques for posterity and came up with the Shueisha Manga-Art Heritage project, which would use specialised printing techniques to make limited-edition versions of manga artworks, which are then made available to buy. A new genre, manga art, was born and Shueisha opened its own gallery in Azabudai Hills in Tokyo in 2023.

Shueisha, which was founded in the 1920s, has a rich back catalogue to draw from. It has been publishing manga since 1949, beginning with monthly magazine Omoshiro (Fun) Book for Boys and Girls, which included such titles as Shonen Oja and was a runaway success. Today, its titles include a manga anthology magazine Weekly Shonen Jump, which has been going since 1968 and is heading towards sales of eight billion copies. As part of one of Okamoto’s gallery projects, he created a new Omoshiro Book with artist Keiichi Tanaami, who remembered waiting every week for the original as a schoolboy.

The Azabudai Hills gallery is divided in two, with one area for exhibitions and the other a small showroom for perusing available artworks. Drawers are filled with exquisite works by big-name manga artists such as Eiichiro Oda, Tite Kubo and Go Nagai. Regular manga printing is already unique in Japan – the cover of One Piece uses five to seven colours, for example, more than any other country would even consider. But the works on display at the gallery are even more vibrant. Okamoto collaborates with the best paper suppliers in Japan and overseas to find the perfect backdrop for the pieces, whether that’s handmade Echizen washi from the Iwano Heizaburou paper mill or Velvet Fine Art Paper from Epson.

Understanding how the manga production process has altered at such a breakneck pace requires some sense of what it used to be. “After the war, it was common to etch the original artwork onto a metal plate, cut out the speech bubble areas and then embed the letters,” says Okamoto. “After 1970, metal gave way to phototypesetting, which involved pasting the words into speech bubbles on the original artwork before the whole thing was turned into a prepress film that could then be printed.” In the mid-2000s, the skilled work of phototypesetting was gradually rendered redundant by the arrival of typesetting software and digital fonts. The final blow came circa 2010, when the whole convoluted process of making printing plates from film plates was no longer necessary; they can now simply be created directly from digital data.

Though the printing of Shueisha’s big circulation manga continues much as it has since the 1970s (rotary printing for those who are interested), everything up to that stage has gone digital. “The typesetting and plate-making processes have been digitised, and companies that can do metal typesetting or phototypesetting don’t really exist anymore,” says Okamoto. An industry that employed tens of thousands and was key to manga production has all but disappeared.

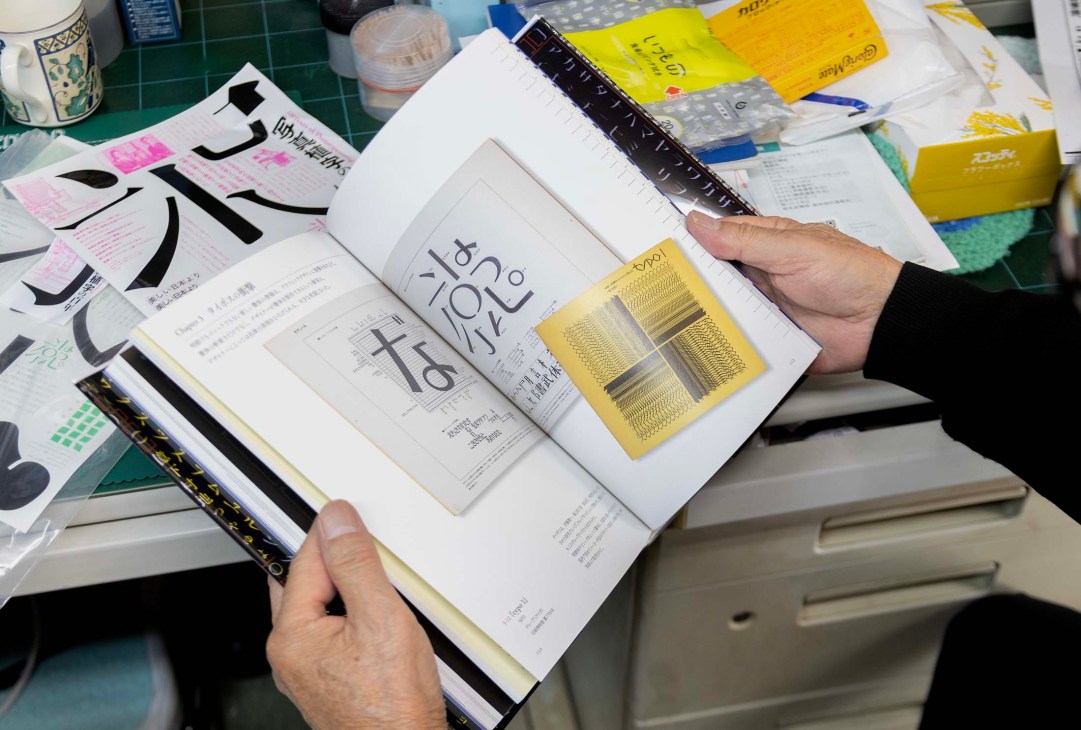

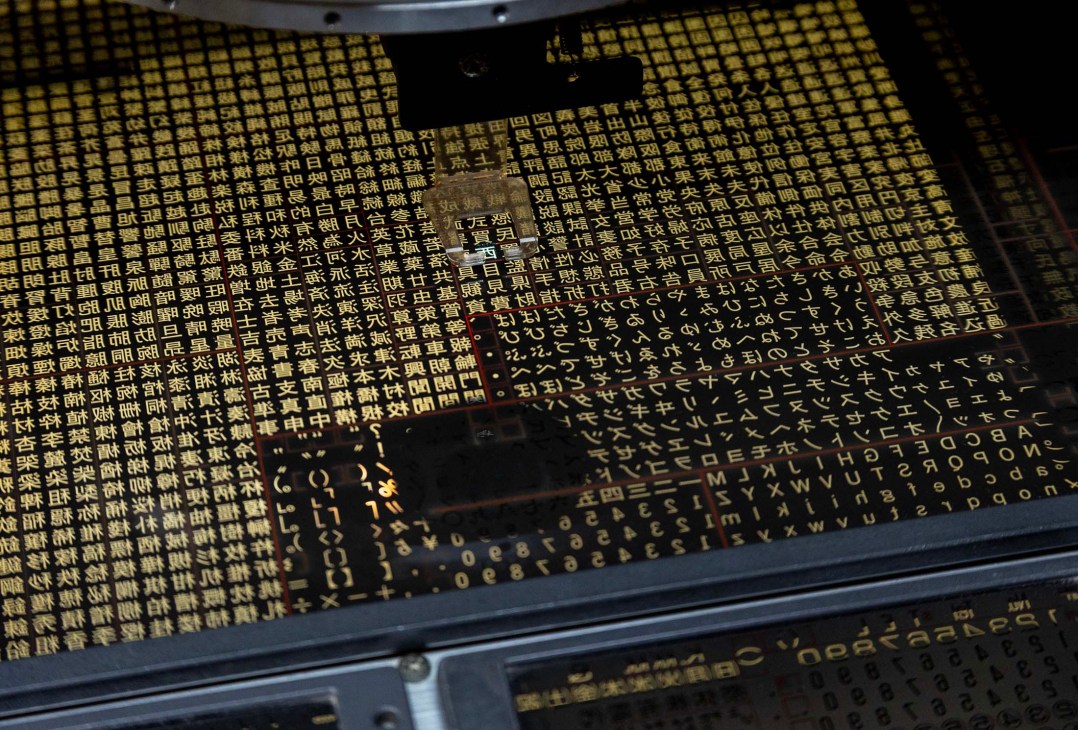

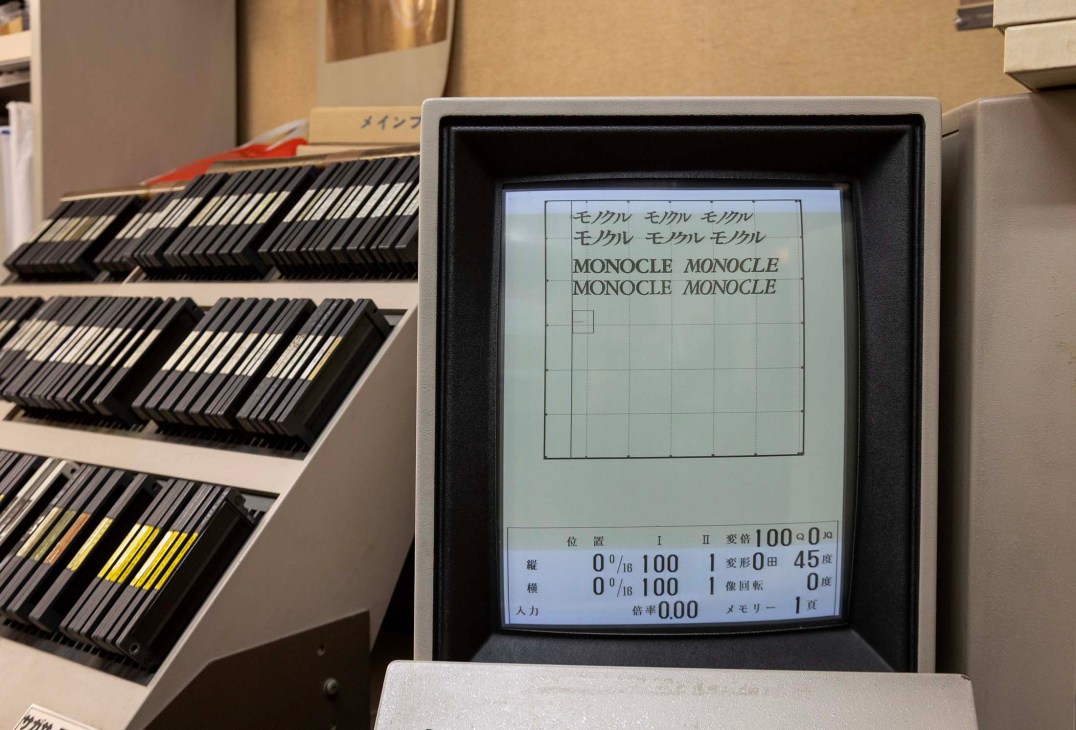

Yasuo Komai is the only phototypesetter still working in Tokyo. When Monocle visits him in his compact studio, a similar machine to the one he uses – a sprawling contraption from the 1980s made by once-dominant Japanese type foundry Shaken – is appearing in an exhibition about the history of printing in Japan. Komai has spent his 60-year career creating the words for everything from book covers to adverts and, from time to time, manga. “Phototypesetting was ideal for manga, where you don’t always have the same fonts or size of lettering and the words change in size depending on speech or emphasis,” he says.

There is a strong sense that Komai is a living piece of a rapidly disappearing past, a man whose skills should be treasured as much as any more obvious traditional craft. Operating the sizeable machine is an impossibly laborious process for the novice – but Komai has decades of experience and works with deft precision, able to judge the precise font, size and spacing for any story or book cover. There’s no room for error since the characters are printed directly onto photographic paper but there’s a human touch and sensibility that he feels a computer can’t replicate.

“Digital is certainly a simpler process but phototypesetting has a freedom that allows for creativity,” says Komai. “The designer will give us instructions but we can fix things that someone else might not even notice and make the whole design more coherent. I bring my own colour to the work. Some authors still specifically request typesetting for their book covers – they know that the quality and dimensions they want can’t be achieved with digital fonts. One problem is that it’s hard to get the materials now – film paper and so on.”

Sensing the near extinction of this skill, Okamoto called on Komai to fire up the phototypesetter to create the words for a new manga from the studio of legendary artist Fujio Akatsuka, which was then exhibited in the Shueisha gallery. Okamoto wanted this done the old-fashioned way. “We asked Komai-san to do the phototypesetting and asked the artist, Yoshi Katta, to use pen and paper,” he says.

Okamoto is also working with a young Tokyo printer, Hiroshi Munakata, who has a 1969 Heidelberg letterpress machine that almost fills his studio in Kagurazaka. When he was setting up the heritage project, Okamoto looked for someone to print on a letterpress machine but could only find a firm, in Nagano, which subsequently closed. He searched again and met Munakata, who had just bought his old printer. “Nobody wanted it,” he says. “It’s a dying technology and most people thought it was too old-fashioned.” Not Okamoto, who has commissioned several pieces from him including a work from One Piece and pages of Keiichi Tanaami’s vibrant Omoshiro Book.

Manga production is a collaborative process and the raw artwork is just one part of it. “Manga is ultimately created with the purpose of being printed,” says Okamoto. “But the original manuscript is an intermediate work, not the final form. Simply printing what is stored in a database wouldn’t have the power of a finished piece. By using advanced printing techniques to maximise the appeal of the original artwork, limiting the production quantity and enhancing its rarity – that’s when it becomes what we’re calling manga art.

“Until now, discussions about manga have mostly focused on the author, the story or the images; the production process is rarely mentioned,” adds Okamoto. “By creating works with letterpress and other printing techniques, I hope that we’re preserving and showing off these techniques.” He’s thrilled that people from different walks of life buy pieces from the gallery; some works are so popular they’re sold by lottery. “Buyers come from Japan and overseas; not only manga fans but art collectors too,” he says. “It’s been interesting to see people who come in and say, ‘I’ve never read One Piece but I want to buy this because it’s a great piece of art.’”

mangaart.jp