Cultural roundup: Mubi moves into book publishing, a petrol station turned gallery in Germany and a Q&A with Martin Bourboulon

Music: Singapore

Loud and proud

Singaporean DJ and entrepreneur Kavan Spruyt found his calling in Berlin. While working for Ostgut Booking, the agency that secures resident artists for the city’s legendary nightclub Berghain, he noticed a lack of diversity in the global electronic-music scene. “There were barely any people of colour on the festival bills,” he tells Monocle.

Spruyt decided to step up as an advocate for Southeast Asia’s electro musicians and opened Rasa in Singapore’s city centre. The 6,000 sq ft space comprises a dance floor, a lounge and a cocktail bar. “I saw the need for a brand that syncs with our identity and represents Southeast Asia to the rest of the world,” says Spruyt. To create a venue that’s worthy of his ambitions, he brought in Berlin-based architecture firm Studio Karhard – Berghain’s masterminds – to design the space. The top-notch fit-out includes Kvadrat acoustic curtains and speakers from TPI Sound that are hand-assembled in the UK.

Two years in the making, Rasa finally opened its doors earlier this year. The stage has been set for Southeast Asian acts to showcase their region’s ever-evolving sound. Artists are increasingly putting cultural inflections into their music, from Thai percussion instruments in producer Sunju Hargun’s tracks to the tropical tinkles in the Midnight Runners’ Indonesian disco. “We know all the rules of the trade and have since learnt how to break them,” says Spruyt.

rasaspace.com

Media: Norway

In safe hands

Trine Eilertsen on how Norway’s media has retained the public’s trust.

Across much of the Western world, confidence in editorial media is declining – but not in the Nordics. In terms of trust, Norway’s media is among the highest-ranked worldwide; at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, when it fell elsewhere, we saw a significant rise. We’re a small society with low inequality, making our country a good breeding ground for this kind of trust. But are there lessons from Norway that could help other nations to increase positive attitudes to their own media?

Politicians here view local media as a useful arena for disseminating information and increasing voter engagement. This understanding of its value ensures that public money – about the salary of one journalist per paper every year – is given to local media in areas too small to be able to support a full newsroom. As in other countries, the consolidation of individual brands into larger groups has saved many Norwegian news outlets. While consolidation might threaten the freedom of a newsroom elsewhere, the editor in chief’s independence is stated in Norwegian law. Decisions about content lie with the editor and the editor alone. Authorities, owners or other forces can’t influence what we publish.

We were also early adopters of digital technology. This has enabled us to develop a more direct relationship with our audience. Our readers tend to come straight to our website, rather than through social media, which makes us less affected by platforms’ algorithms. Meanwhile, paid online subscriptions are popular; indeed, Norway’s audience has the world’s highest propensity to pay for news.

All serious Norwegian editors abide by the national press’s code of conduct and anyone can make a complaint to the ethics commission. The members of the latter are other editors and ordinary people who discuss whether the code has been broken. If it has, editors are obliged to publish a correction. Like every media outlet, we still have to fight for our audience but these are some of the reasons why, when readers come to us, they can rely on what we say.

Eilertsen is the editor in chief of ‘Aftenposten’, Norway’s leading printed newspaper in

terms of circulation.

Publishing: UK

Picture perfect

Fresh from a banner year in which Coralie Fargeat’s satire The Substance took the world by storm, London-based streaming platform, production company and film distributor Mubi is launching its latest venture: a publishing arm focusing on books about cinema and the visual arts.

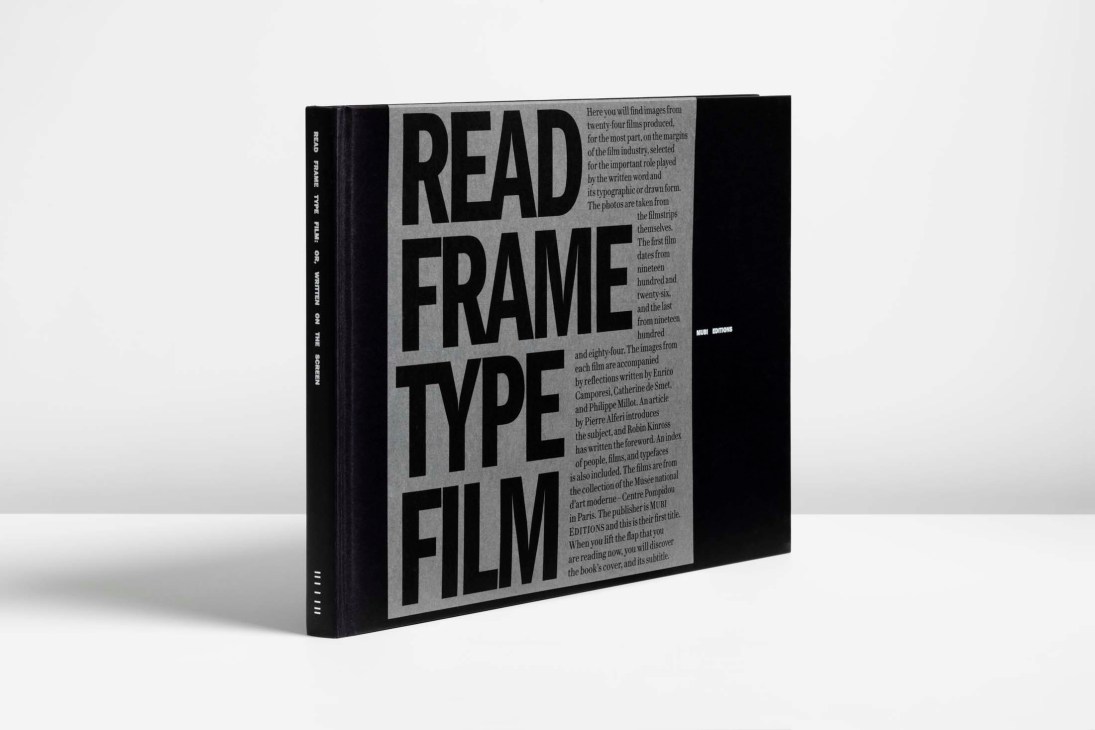

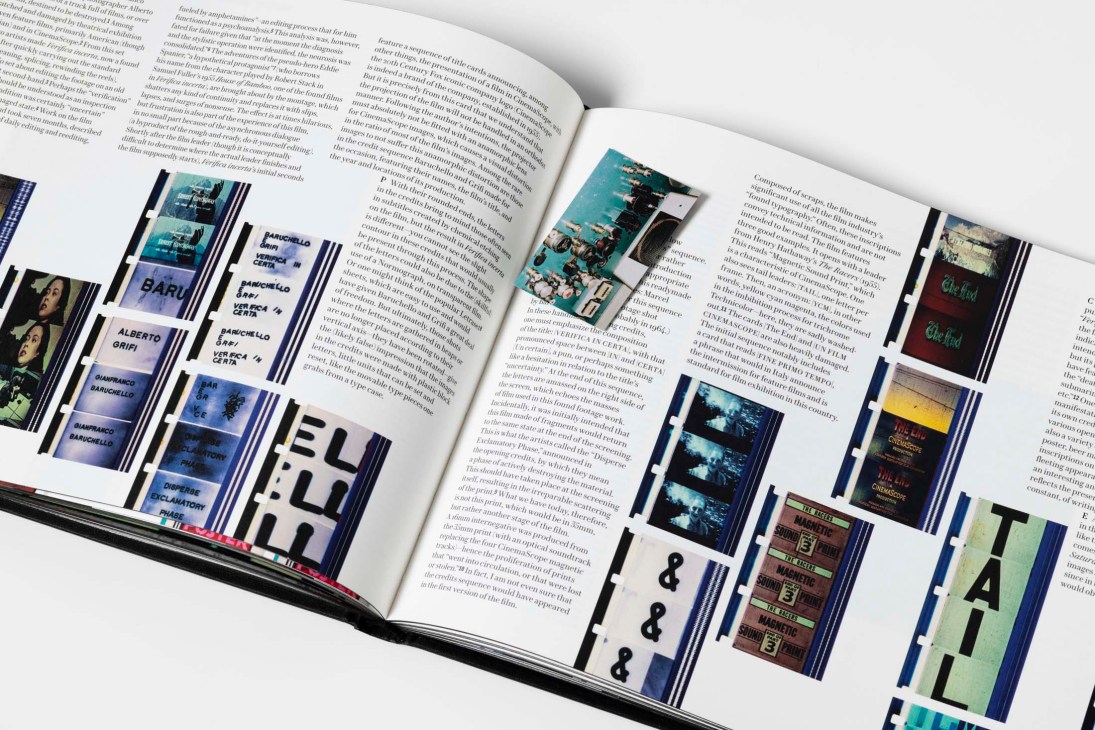

Mubi Editions’ first release, Read Frame Type Film, is a collaboration between film curator Enrico Camporesi, graphic-design historian Catherine de Smet and designer Philippe Millot. Drawing from a research project initiated at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, it explores the affinity between film and typography.

“We are challenging ourselves to do something different and surprising for the audience,” says Daniel Kasman, Mubi’s vice-president of editorial content. “That means looking for the unexpected, for what is unusual and delightful. It’s hard to do but the surprise is the goal.”

‘Read Frame Type Film’ is published on 22 May.

Television: France

Q&A

Feast for the eyes

Martin Bourboulon, director

Marie-Antoine Carême was arguably the world’s first celebrity chef: in the 19th century he served European royalty and some of the leading politicians of his era. Carême, a new drama on Apple TV1, brings his story to life. Its director, Martin Bourboulon, tells us about putting pâtisserie front and centre, and showing off Paris’s beauty.

Why is Marie-Antoine Carême a good subject for a TV drama?

I wanted to bring a modern vision to his story but was also excited to work on a show with a range of different themes: politics, food and sex. Carême is a chef but also a spy. It’s a French show for a global audience.

How did you approach directing the kitchen scenes?

You have to find a good rhythm between the plot and those precious moments in the kitchen. When we were showing Carême making the dishes, we took our time with a lot of close-ups.

Paris is almost a character in the show. How crucial was it to immerse viewers in the city?

It was important for us to show Paris, especially with wide shots, because it’s so recognisable to an international audience. But it was difficult because it’s 2025 and our story took place two centuries ago. In some of the beautiful wide shots, if the camera had turned a little to the left, the vision of an old Paris would have been spoiled.

Art: Germany

Life’s a gas

Just a stone’s throw from the Swiss Galerie Judin, which moved from Zürich to Berlin’s Potsdamer Strasse in 2008, is its striking new collaboration with the US-founded Pace Gallery. “It’s an urban oasis,” says Pay Matthis Karstens, co-owner of Galerie Judin.

The exhibition space, café and bookshop is based in a converted 1950s petrol station in the buzzy Schöneberg district. Buildings of this kind were once a common sight across Berlin but many have fallen into disuse and disrepair. Indeed, the site that was chosen for this project was abandoned in 1986 but was renovated 20 years later; it served as an architect’s home and then a museum until late last year. Now, Pace Gallery and Galerie Judin are its proud custodians and the floor-to-ceiling windows that once looked out at fuel pumps and bmw Isettas instead frame a peaceful courtyard.

“It has a certain meditative feeling,” says Karstens. “You have the sounds of chirping birds and the trickle of water. It’s not that the city totally disappears but it creates moments of calm.”

The garden is framed by tall stalks of bamboo and a water feature putters in the centre. Inside the old filling station that used to sell petrol and cigarettes, Pace and Judin will take turns organising exhibitions. The mélange of businesses at this new spot encourages Berliners to slow down and take time to absorb the art – to sit, ponder and discuss what they have seen. It’s much more rewarding than just getting your fill and zooming off.

The exhibition space opened to the public in May. For more details about what’s on, visit: pacegallery.com and galeriejudin.com

Music: New Zealand

Chaos theory

On his new album, Te Whare Tiwekaweka, Marlon Williams sings in a language that he can’t quite speak. “In 2019 I had a melody floating around my head that I couldn’t shake,” he tells Monocle. “It suddenly became clear that it was a Maori melody – like the songs from my childhood.”

Williams’ parents are from two Maori tribes. Though the musician went to a Maori language school at the age of five, he later stopped using the language. “My language skills are limited,” he says. “But I muddled my way through, adding lyrics, and the song was so pleasant to sing that it gave me the gumption to commit a whole record to the Maori language.”

The project was inspired by Williams’ emotional homecoming after touring his 2022 album, My Boy. “When I came home I saw a charcoal drawing at my mother’s house depicting

a tall, slender man in a top hat returning to a villa at night,” he says. “This man is approaching a ladder and carrying a suitcase full of money – British sterling. I identified strongly with the image of this rakish man coming home, returning with a bag of foreign currency. I asked my mother about the drawing and she said, ‘I was pregnant with you when I drew this.’ It immediately became a central part of the record.” The image is now the cover art for TeWhare Tiwekaweka.

The album’s title comes from a Maori proverb that roughly translates as “messy house”. “I’m a bit of a messy person on the most fundamental level,” says Williams. “For me, it really speaks to the seed of creation and how new things come out of chaos. Nothing interesting ever comes out of something clean.”

‘Te Whare Tiwekaweka’ is out now.