After seven decades of creativity, David Gentleman shares advice for aspiring artists

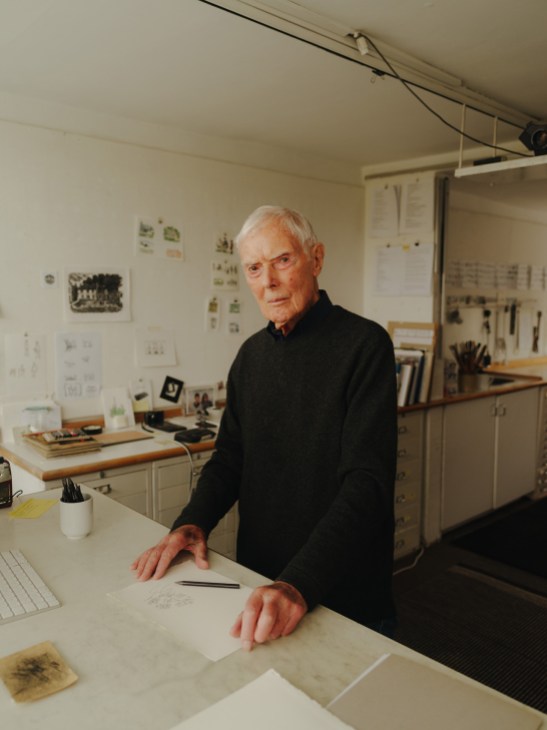

At his north-London studio, the much-loved English artist shares insights and golden rules gleaned from his long career.

In an era when the online world offers an endless spew of just-minted hacks, short cuts and “12 Reasons Why…”, just who is 95-year-old David Gentleman to be offering lessons for young artists? Well, for a start, he’s the maestro behind some of the most longstanding, recognisable and beloved works of art and graphic design made in the UK since the 1950s – work also acknowledged and cherished worldwide. So it’s quite right that you sit up and take notice of Gentleman’s golden rules. After studying at London’s Royal College of Art under Edward Bawden and John Nash, Gentleman chipped and then rocketed away to become a garlanded public success who’s still at it: making work and publishing books, the latest of which is Lessons for Young Artists.

“Do it every day, even on holiday,” says Gentleman of making creativity a habit. It’s a statement that he has lived up to, spending five decades of a 70-year career in the top-floor studio of his Camden home, daily adding to a dizzying body of work: watercolour landscapes and corporate logos, charming illustrations and era-defining book covers, collections of celebrated postage stamps and righteously angry protest placards. It’s this broad swath of work – as engaging as it is engaged – and a lifetime of learning that are at the heart of Lessons for Young Artists.

Enlightenment is offered in short chapters with deceptively simple headings, accompanied by Gentleman’s beguiling images: “Start small”, “Travel light”, “There are no rules”. These draw on deep knowledge wrought plainly to remind artists young and old to think about simplicity, to be nimble and ready, fearless and bold. The first chapter is accompanied by a pencil sketch of Suffolk trees from 2024 and a painting of some toys executed by Gentleman in 1936, when he was just six. It’s lovely to witness the work of an artist’s hand across an almost 90-year span. And that’s a vital lesson in itself: keep on keeping on.

In a chapter headed, “Say ‘yes’ to the unexpected invitation”, we see his designs for Royal Mail stamps after their decades of dullness. Then logos for British Steel and the National Trust and a groundbreaking relationship with Penguin books, for which his best-known work is the re-presenting of Shakespeare’s plays for mid-1970s paperbacks that mixed playful, organic woodcuts with the clean modernity of the Helvetica typeface. Gentleman’s work has enchanted millions of people, yet his selfless style has never wrestled a commission into becoming “a Gentleman”. With winning magnanimity he confesses, “I’ve never had any interest in consciously trying to develop a style.”

While Gentleman’s tone of voice is pleasantly fatherly (“Tidying the studio is a cheerful way of coping if a piece seems to be going wrong”), he’s also cut from a similar cloth to the great William Faulkner, who said, “I write when the spirit moves me – and the spirit moves me every day.” Indeed, the book’s final chapter is titled “The only way to become an artist is to do it”. No pop-ups, no hacks, just a beautifully designed, wellbound little hardback. It is, of course, not really a book about art but about living life, and to a ripe old age. A lesson, then, for everyone.