Every object has a story to tell – and V&A London’s new storage facility is designed to serve as a museum

Monocle takes an exclusive look behind the scenes of London’s new V&A East Storehouse that’s not just demystifying the work of curators and conservators, but also redefining what a museum can be.

At one point during the installation of the Torrijos ceiling in V&A East Storehouse, 12 different parts of the carved wooden roof dangled from chain hoists. With painstaking care, a team of technicians clad in hi-vis and hard hats slowly tried to manipulate them into place.

We don’t often look at ceilings, the sides of buildings or entire rooms, for that matter, and consider them “objects”. The meaning of the word, however, begins to expand as you wander through this new museum-cum-warehouse. V&A East Storehouse is the latest member of the V&A family, a storied British institution founded in 1852 and named after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Unlike its existing museums in London, Stoke-on-Trent and Dundee, V&A East Storehouse is more like a storage facility that has been designed to allow visitors inside. There are publicly accessible art storage facilities elsewhere, most notably the Depot of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, but nothing on the scale of this new institution.

V&A East Storehouse was born, in part, out of necessity. In 2015 the UK government announced plans to sell off Blythe House, a government-owned London storage facility that has housed most of the V&A’s stored collection since the mid-1980s. About 600,000 objects, books and archival collections would have to be relocated; some larger objects, such as the Torrijos ceiling, were being kept in storage in Wiltshire and these were swept along into the plan. “You don’t move a collection of this size and scale very often,” says Tim Reeve, deputy director and chief operating officer of the V&A. “It made us think that we had to go as big and be as ambitious as we could.”

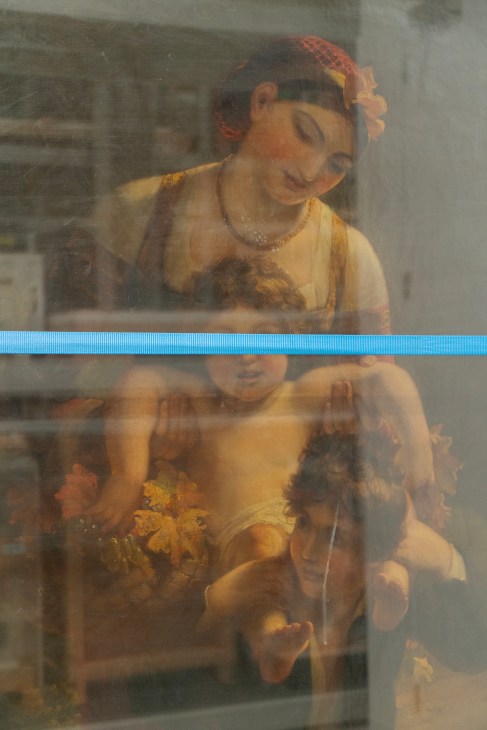

That ambition eventually translated into unboxing the 500-year-old Torrijos ceiling to install its eight interlocking arches and corner pieces (or squinches) here. The ceiling was created in the Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella, for a palace near Toledo. Just before the palace was demolished, the ceiling – one of four – was acquired by a London art dealer and, in 1905, sold to the V&A. For more than 80 years, the Torrijos ceiling was installed in the museum until, in 1993, it was dismantled and packed into 40 large crates.

When the ceiling was unboxed, some of the timber framework had warped and the pieces no longer matched up. “We had some sketchy old plans but there are about 150 pieces. It was just a massive jigsaw,” says museum technician Allen Irvine. “I’ve worked with the V&A for 21 years and that’s one of the most difficult installations we’ve ever had.” Completing the jigsaw – modelling how the octagonal dome fits together, building additional timber to support it, working with conservators and fixing the six-by-six metre ceiling in its tight space – took three months. “It’s an absolutely dazzling piece,” says Reeve. “Now we see it, I think we all feel guilty that it’s been off public display for so long.”

The Torrijos ceiling is one of five “large objects” that have been incorporated into the architecture of this space. They are testament to the ambition of the building’s design as well as that of past V&A collectors. They include an office designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and an example of a fitted kitchen from 1920s Frankfurt. The section of the façade from Robin Hood Gardens, an iconic east London brutalist tower block that was demolished between 2017 and 2025, was the first thing installed here more than three years ago, when the museum was just a building site. Now that 12-tonne concrete façade fragment lives in the centre of V&A East Storehouse, looming over the stairs through which visitors climb to arrive at the collection hall.

It’s a theatrical entrance amplified by the way the space seems suddenly flooded with natural light. But in fact this is provided by a lightbox created with a huge stretched Barrisol ceiling (“If size matters, this is the largest Barrisol ceiling certainly in Europe, maybe even the world,” says Reeve). It gives the perfect illusion of daylight without having to worry about capricious British weather. The museum’s hollowed-out core is the first space that visitors will experience, which makes V&A East Storehouse “a typical building inside-out,” says Elizabeth Diller, a partner at Diller Scofidio and Renfro, the New York-based architect firm behind the project. “In most public institutions, if one goes deeper and deeper into the footprint, one goes into more private spaces,” she says. Here, the further out you move, the less accessible it becomes. The inside-outness of the layout “gives the public a sense of trespass”, says Diller.

As you arrive, it’s hard to know where to look. The publicly accessible galleys, which surround the central space, are lined with industrial shelving units whose rack ends hint at the variety within. Glance around the room and you’ll see an elaborate Dutch “giraffe piano”, a Memphis Milano lamp, a Venetian bust and a multicoloured rubbish bin extricated from Glastonbury Festival. “There is something for everyone,” says Reeve. Where the objects go and who they sit next to has been lightly curated but visitors will take themselves on a self-guided tour. There’s no exhibition per se, no one story to be learnt or single message to take away. “Part of the motivation of the project, and what gave us great joy, was to figure out a way of expressing the vastness and eclecticism of the collection in a way that could be sublime,” says Diller.

For the displays, the architects “took as a model the eclecticism of a cabinet of curiosities”, says Diller. Made popular in Renaissance Europe, these were rooms in which collectors brought together their prized objects for the enlightenment and entertainment of others. At V&A East Storehouse, the simple, stripped-back appearance of the displays adds to the feeling that you’re drawing back a curtain and going behind the scenes. Objects are displayed in wooden crates and on specially designed palettes. Busts are strapped into place with criss-crossing cushioned seatbelts. Every object has a simple luggage tag tied to it with a code that can be looked up on the V&A’s digital database.

The public experience of V&A East Storehouse as a museum exists side by side with its purpose as a working storage facility. A glass floor in the central area, which gives the illusion of being propped up by a vast and ornate Mughal-era colonnade, gives visitors a view of what’s happening below. There, forklifts and other machinery roam the lower labyrinths of the building (it took over two years, says technical manager Matthew Clarke, to find the necessary equipment to handle heavy objects in narrow aisles without a standard palette size). When Monocle visits, we watch a 19th-century French vase with detailed goat heads for handles being manoeuvred onto a forklift and lifted into place. Once the museum opens, visitors will continue to see the technical team at work as they rotate the displays and move objects for exhibitions or to go on loan.

Deeper into the building, there are conservation studios, reading rooms and a cloth workers centre, all of which are publicly accessible. Overlooking the conservation studios is a window for visitors to peek at what’s going on inside. These studios are also equipped with headsets and cameras that conservators can use to give curious visitors more details about what they’re working on. Museum-goers might be used to seeing the work of curators but Reeve hopes to demystify other roles, such as conservators or technicians. “It’s getting visitors into all corners of what we do to care for a collection of this size and scale,” he says.

As well as exposing the lesser-known activities of museums, V&A East Storehouse extends an open invitation to visitors to take a closer look at its collection through the Order an Object service. Kate Parsons, director of conservation, collections care and access at the V&A, describes a new part of her role as providing “meaningful and equitable access to every part of every object on this site”. Everything in the building has been logged and anyone can search through the digital catalogue, put up to five objects in a “virtual crate”, then choose a time and date to come in and have a look. “A booking is a booking,” says Parsons. “It’s not a request. You decide you’re going to see these five objects and we enable access.” What that means in practice depends on why an object has piqued your interest. If you’re a cabinetmaker, says Parsons, you might want to see the back of a drawer to find out how it’s been made. If you’re researching shoes for a television drama, you might want a face-to-face with one of the 3,500 pairs here. But you don’t have to be a cabinetmaker or researcher to use the service. “We are very clear that there’s no need for credentials or a reason to look at something,” says Parsons. “People can choose to see things just because it might make them happy.”

Parsons has just finished the recruitment process for the staff who will enable this access. Those who were chosen didn’t need to have experience in museums. Instead, prospective employees were asked to talk about an object they own that is precious to them and how they keep it safe. “That simple question was amazing in terms of the stories we heard,” says Parsons. Important, too, was recruiting from the local area. “We want people who are living and working in East London to feel like this can be part of their lives, as a hobby but also a profession,” says Reeve. Keeping things local, the museum café is run by East London bakery E5 Bakehouse. And V&A East Storehouse isn’t the only new institution here. Dance venue Sadler’s Wells East opened earlier this year, while the David Bowie Centre will be finished later in 2025 on the Storehouse site. Next year, V&A East Museum, a more traditional museum that will act as a sister venue to Storehouse, will open too. “East London has a great creative heritage,” says Reeve. “But research tells us that a large population in East London are not museum-goers. We want to make them feel welcome here.”

As Reeve walks past one corner of the collection hall, he throws his arms wide, encompassing a Piaggio scooter customised by architect Daniel Libeskind, a drum kit that belonged to Keith Moon and a vase with sphinx-shaped handles. Thousands of miles and hundreds of years of history swept up in one arm span. On show, too, are the straps, screws and supports that hold all these objects in place. “This is what it’s all about,” he says, beaming.

It’s these objects that take centre stage here, and the hundreds of thousands of them at V&A East Storehouse tell us infinite stories. Stories that can’t be heard from outside the locked doors of a closed storage facility. Stories that aren’t just of the objects themselves but of all those who’ve had a hand in helping them along the way. The hands that sketched, stitched, carved, crafted, restored; that used an object, made it famous, threw it away, decided that it was worth keeping or, lovingly, winched it into place.

Hear an audio version of this story with extra interviews on The Urbanist:

Hear four young people reflect on their experience telling the stories of Robin Hood Gardens alongside the V&A on The Urbanist: