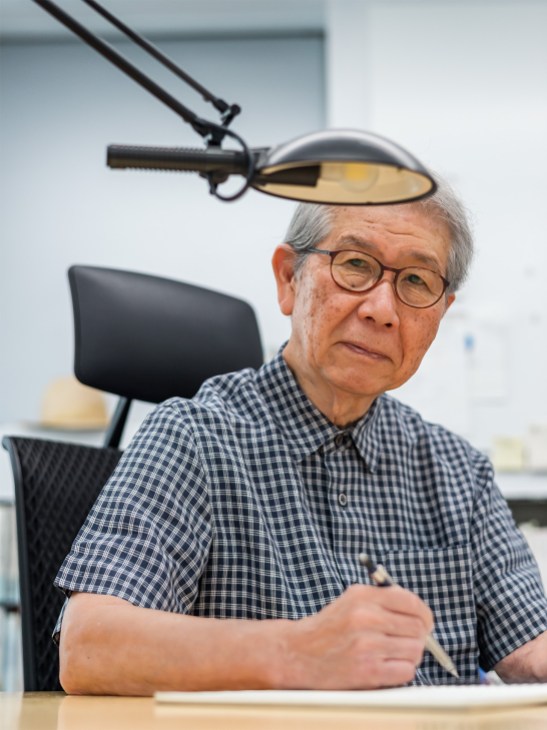

Pritzker Prize winner Riken Yamamoto on creating spaces that connect people and generations

Discover how Yamamoto’s approach to public and private space creates architecture that nurtures community and memory.

Riken Yamamoto was born in Beijing. Shortly after the end of the Second World War, he moved with his family to Yokohama, where they lived in a home modelled on traditional Japanese machiya – long wooden townhouses with a shopfront and interior courtyards. His mother’s pharmacy faced the street and the living quarters were at the rear. “The threshold on one side was for family and, on the other side, for community,” says Yamamoto. “I sat in between.”

It’s a position in which the 80-year-old architect still finds himself: his long career has been defined by an architectural approach that reconsiders such boundaries. His portfolio – which includes Yamakawa Villa (1977), a residence that is open on all sides, and The Circle (2020), a mixed-use hub at Zürich Airport – expresses his design outlook physically. The architect is also articulate when it comes to explaining his ethos.

“The current architectural approach emphasises privacy, negating the necessity of societal relationships,” he said when accepting his Pritzker Prize in 2024. “But we can still honour the freedom of each individual while living together in architectural space, fostering harmony across cultures and phases of life.” In short, the blurring of indoors and out, public and private, has the potential to build not only better personal spaces but stronger communities too.

The notion of community often comes up when you discuss what drives you in your work. How can architects help to create feelings of belonging?

It’s important to speak with the people who will be using the building or space. Communication is the most crucial thing for me in my work, because it allows me to understand what I should create, what kind of architecture the space is calling for and how it can contribute to dialogue. The work of an architect is to foster communication – with a client, with the user and even with tourists who are visiting a space temporarily. This is the power of architecture.

You have worked in many countries and markets, blending this notion of public and private. Are there any specific challenges associated with having a global practice?

I don’t find it challenging because the first thing that we do with every project is decide what public and private mean in that context: in other words, we ask what the relationship is between the building and what’s outside. This applies to everything, from a client wanting us to deliver an airport to creating a small house for an individual. It doesn’t matter if it’s a big tower, a different country or a new culture. The basis is always the same: to understand what the meaning of public and private is.

Earlier this year, when you received the Crystal Award at the World Economic Forum, you mentioned that architecture acts as the memory of a community. Can you explain this?

Architecture is powerful because our built environment is a manifestation of our collective memory. And architecture is the present community’s touchpoint for the next generation – we might come and go but what we build remains. Many generations will use the same building; they will be born and die with that space as part of their lives and it will be a symbol, a memory of the community that inhabited it before us. Architecture allows and encourages people to remember.

Do you find that is the case for all architecture?

Architecture can either foster and help to build a community or not. That is a decision entirely made by the architect. I’m always trying to help instil that philosophy, the sense of community and belonging. Doing so is what brings people back to their community. Think of your hometown or the house where you grew up. Many would like to go back to a certain place from their past because there is a memory of the community there – not just their family but how life was together with their neighbours. It’s crucial that we create spaces where people can live together because that’s the true meaning of community.

This conversation is timely, given that there are wars in Europe and the Middle East that are currently tearing groups of people apart. What role can architects play in rebuilding communities?

It’s difficult because everything is being destroyed – not just buildings but entire villages. That’s very dangerous in terms of the continuity of a community. When the time comes, we should keep the architecture and rebuild, even if it’s a very small thing. Doing so brings back important elements. For instance, right now, almost all of the architecture in Gaza has been destroyed and in Ukraine places are also disappearing. But something similar happened in Japan after the Second World War when many places were destroyed by US bombing. After that, we had no tradition left. It changed the way we think. From that moment onwards, we knew that we needed to preserve and fight for architecture because otherwise you’re destroying memory.

What is the one thing that you would like to pass on to the next generation of architects?

Honour the plight of the community. And ask yourselves, “How do we keep fighting?”