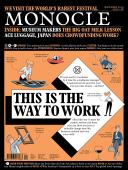

Issue 126

Monocle’s Entrepreneurship-focused September issue is dedicated to those who’ve struck out on their own – and those considering it. We’ve also amassed a timely toolkit for the business-minded buyer, whether you’re starting a new venture or rethinking an existing one.

In This Issue

Oops! No content was found.

Looks like we no longer have content for the page you're on. Perhaps try a search?

Return Home