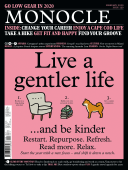

Issue 130

The fresh-feeling February issue of Monocle is home to our Gentle Manifesto for the year ahead: simple fixes and friendly nudges to make this year better than the last. Inside you’ll find an urban experiment in Cartagena, tales from the folk who quit their jobs and followed a different course, and a new museum in Miami. Plus: Amanda Lear’s ‘last meal’, the road to architectural enlightenment in Rouen and some sporty suggestions for 2020.

In This Issue

Oops! No content was found.

Looks like we no longer have content for the page you're on. Perhaps try a search?

Return Home