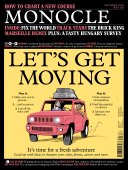

Issue 136

Monocle’s September issue celebrates the marvels of mobility while issuing a call to arms for us all to get outside and make the most of our cities. In a packed issue, we profile the transport movers making it a pleasure to get from A to B and highlight the small cities you’ll want to settle in to start your next venture. Plus: a tasty Hungary survey. Let’s get moving.

In This Issue

Oops! No content was found.

Looks like we no longer have content for the page you're on. Perhaps try a search?

Return Home