- Issue 14

- January 2024

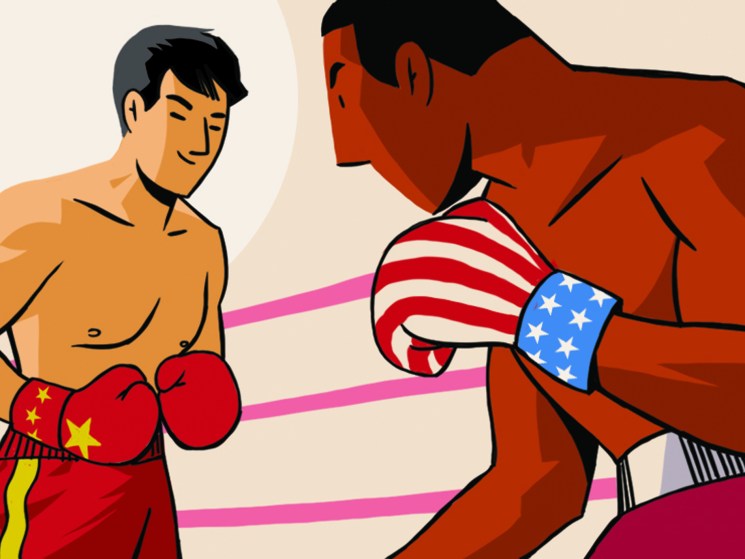

The Forecast

Monocle’s handbook for the year to come – and why there’s lots to look forward to.

+ Our annual guide to the world’s best small cities – for business, nature and being happy.

In This Issue

- 14 | The Forecast

- 12 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 6 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 5 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 9 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 5 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 29 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 14 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 12 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 16 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 8 min read

- 14 | The Forecast

- 27 min read