Mediterraneo

The radical notion of the ‘Mediterranean spirit’ and why we need it now more than ever

In our fast-moving world, the Mediterranean feels like a refuge, both metaphorically and physically. It’s a place where time doesn’t rush. Last summer almost 330 million tourists arrived on its sandy fringes in search of peace. People might say that they’re coming for the sun and the sea but that’s not quite all of it. The light is different here. The pace is slower. What they’re really chasing is a sensibility, a rhythm, a way of life that doesn’t involve to-do lists or deadlines.

French-Algerian writer Albert Camus called this the “Mediterranean spirit”. He was just 23 years old when he stood at the Maison de la Culture in Algiers in 1937 and began to articulate something that many of us still sense. For Camus, the lightness of this spirit was inseparable from the darker, existential awareness of life’s absurdity, which informed his work, writing and philosophy.

The absence of inherent meaning in the world didn’t lead him to nihilism. Inspired by the Mediterranean, he called instead for us to seek a quiet resolve and live in harmony with one’s surroundings. “What is happiness except the simple harmony between a man and the life he leads?” he wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus. To him, harmony was the cure for life’s absurdity and the Mediterranean spirit was his North Star.

Born in Algeria to French parents, Camus was suspended between incompatible allegiances. He was French but not quite; Algerian but never enough. He was a stranger to both and at home in neither. I too have lived at such an intersection, experiencing a similar dialectic. Born to European parents, I came of age in Turkey, a country forever negotiating its place between East and West. The tension of not fully belonging anywhere resulted in a constant sense of estrangement and searching. Like the Mediterranean, my life lapped many shores.

Many influential and itinerant 20th-century writers shared this sense of not belonging. Philosopher Hannah Arendt, who chronicled the trials of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, found refuge in calling the German language her home. Palestinian-American academic Edward Said described himself as always “out of place” and discovered a form of home in exile. For James Baldwin, whether he was in New York or in Saint-Paul de Vence on the south coast of France, home was found

in the moral clarity of his writing.

All of these writers had a connection with at least some corner of the Mediterranean but Camus overcame his strangerhood by calling the entire Mediterranean his home – not France, not Algeria. I understand what it means to belong to a climate, rather than a country: a home shaped by the sun, the sea and the play of light. That home is also mine. Camus’s belonging was about building a relationship with one’s surroundings – an act of guardianship, tending to a landscape, a pace of life. It was not belonging in the widely understood sense. It was about being a custodian of things that made one’s inner life flourish. The idea is as useful today as it was then, as many of us sit divided by politics or in cities far from nature, family or a sense of community.

More than four billion people live in cities today; by 2050 that figure will more than double. Urban life has become the default but the question of belonging grows harder to answer. We occupy flats where neighbours remain strangers. We spend hours isolated in cars or in overcrowded train carriages. It’s a solitude that is collective, an urban loneliness that connects us only through our shared disconnection. Technology promised to bring us together but delivered distance. It all becomes even more unsettling when technology moguls suggest AI as a solution to our shared loneliness. Meta’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, talked recently about a future in which the majority of your friends might be AI. Who could possibly want that? Not me, nor many people I know. That’s a world in which few people could belong.

That is why we need the Mediterranean spirit more than ever. Not as a gimmick or a beach escape but as a kind of rebellion and a reset. What will save us is not another algorithm but the stubborn act of feeling alive and connected – to the Earth and to each other. The summer can be a moment to remember why we’re here and the simple pleasures that can’t be optimised on spreadsheets: the sun-warmed tomato, the cool beer in the midday sun, the act of submerging yourself in water. The Mediterranean refuses efficiency. It resists the logic of schedules. The Mediterranean, not Silicon Valley, gave us la dolce vita and no amount of machine learning could improve that.

De Cramer is an Istanbul-based journalist. She is a frequent contributor to Monocle and its sister publication, ‘Konfekt’.

All eyes are on Corsica, as a vote on its greater autonomy – or even full independence – from Paris approaches

Known for its pristine beaches and wild interior, the Mediterranean island of Corsica attracts three million visitors a year and largely stays out of international headlines. But beneath its bucolic façade lies a complicated history, one that threatens to upset the island’s picture-postcard image. Le problème corse centres on nationalist demands by political parties such as Femu a Corsia for more autonomy – and in the case of Corsica Libera, total separation.

Though local powers were extended in 2018, Corsica’s leaders want autonomous powers written into the constitution. The conundrum for the country’s president, Emmanuel Macron, and its prime minister, François Bayrou, is how to resolve the dispute without it causing further problems when the issue is meant to go before a vote in the National Assembly later this year.

Corsica was ruled by the Kingdom of Genoa for almost 500 years until it was annexed by France in 1769. Since then, its culture and language, more similar to Italian than French, have meant that it has felt removed from l’Hexagone. From the 1970s to the 1990s, when separatist militant group the National Liberation Front of Corsica (FLNC) laid down its arms, the island’s independence movement was riven with violence. While things are calmer now, the legacy of those years lives on. The island has the highest rate of gun ownership in France, with almost 350 weapons per 1,000 inhabitants, more than double the national average. The last separatist clashes came in March 2022, when Corsican nationalist leader Yvan Colonna was beaten to death by a fellow inmate in a mainland prison. Protests spread from Ajaccio and Bastia to other cities; 77 police officers were injured.

That unrest, which came less than a year after the flnc threatened to return to armed struggle in their pursuit of Corsican sovereignty, convinced Macron to act. The subsequent negotiations, dubbed the Beauvau Process, led to a series of meetings between Corsican and national officials. These yielded a breakthrough in March 2024 – despite sticking points over the status of the Corsican language, the central government recognised the idea of autonomy for Corsica “within the heart of the republic”, a concept later approved by the Corsican Assembly.

The vote on autonomy by the National Assembly is expected in the autumn and many European leaders with separatist problems of their own will be watching. Some in France are fearful that giving Corsica further powers could prompt other regions, such as Brittany, to try to follow suit. But if Paris denies the wishes of Corsica’s leaders, things could turn ugly on the island once more.

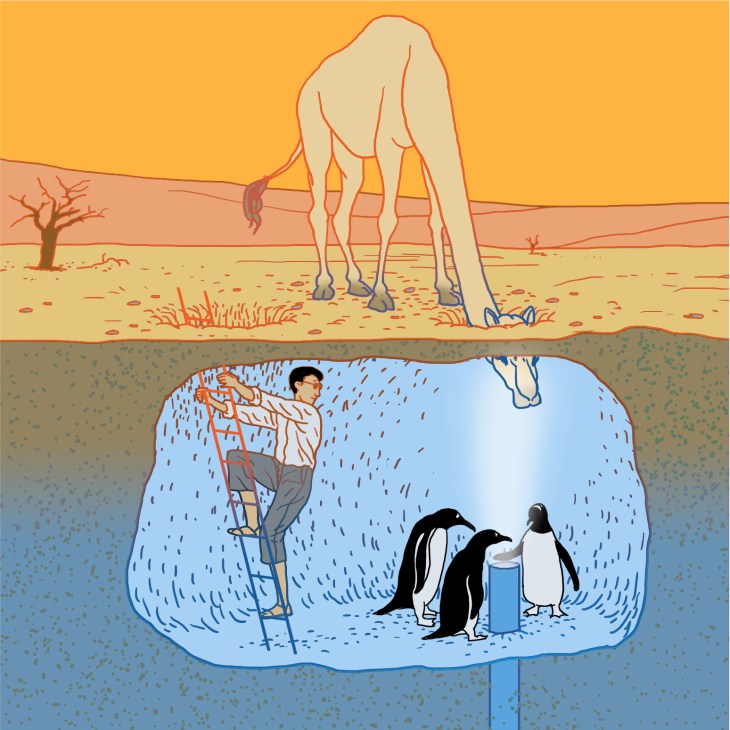

How to tap nature’s chilling effect for a sustainable way to cool urban areas

Some of the world’s first air-conditioning units were installed in the 1930s in the offices of Bahrain’s national petroleum company, Bapco, shortly after the nation struck oil. Today energy produced by oil is still used to alleviate the effects of rising temperatures, which are a consequence of drilling and burning it.

But for the Heatwave exhibition at the Venice Biennale’s Bahrain Pavilion, I came up with a new public ventilation and cooling system – alongside engineers Alexander Puzrin and Mario Monotti – that could be deployed in the region and globally. The design is very simple. A metal pole holding up a square canopy is sunk into the ground and points up to the sky like a chimney. The technology is similar to the geothermal wells used to heat houses in northern Europe, except that instead of water, air is being pumped. In the Gulf, summer temperatures reach nearly 50C but if you dig 15 or 20 metres below ground, you reach a layer that has a stable year-round temperature – in Bahrain, this is about 27C. The pipe brings hot air underground to cool it, then distributes it through “air showers” hidden in the canopy. We needed only one low-energy ventilation pump to cool the entire covered space.

My idea came from an elemental principle: the axis mundi, or the connecting line between the ground and the sky. Trees use their roots to tap into cooler soil and can release heat as excess moisture through their leaves. Similar ideas can be found in the traditional architecture of the Gulf region, where badgir chimneys capture the wind and direct air inside homes. Food that can be affected by heat is often stored in cooler semi-underground tunnels. These ancient systems use simple thermodynamic principles to deal with a hot climate with no need for an external energy source.

In the Gulf today, people rarely leave air-conditioned indoor spaces. This results in high energy consumption; meanwhile, the appliances only work in rooms that are closed to their surroundings. Our pavilion instead tries to adapt to the context by creating a microclimate without walls. Anyone with even a passing grasp of how hot air rises can see how it works. Instead of building protected boxes for people to live in, we should try to understand a place and work with natural principles.

In the future a large part of the island of Bahrain could be almost uninhabitable in the summer. Before the modernisation of the country, people living there would move to cooler parts of the mainland for the season and then return in the autumn. This type of migration has been crucial in many regions across the world. Today we are hemmed in by private property, jobs and the commitments of the modern world. We are confined in one space but not really able to exist sustainably. We must reconsider how we protect ourselves in negotiation with the environment, rather than by treating it as the enemy.

Berlin-based Faraguna studied architecture in Venice. This essay is from the 2025 Venice Biennale special edition of The Monocle Companion. As told to Monocle’s design correspondent, Stella Roos.

Read next:

Seville, the ‘frying pan of europe’ holds the secrets to managing the blistering summer heat

How to cool cities naturally, without air conditioning

How to make a hot night in the city feel perfectly cool

Seville, the ‘frying pan of Europe’, holds the secrets to managing the blistering summer heat

On a mid-afternoon in late May, people cram themselves into the narrow strips of shade between buildings in Seville’s Triana district. This sort of basic temperature regulation comes naturally to Sevillanos. Heat is baked into the city’s history and therefore its architecture – from the Islamic-era narrow streets and cool internal courtyards to the shaded bus stops and street sprinklers of the Andalusian capital’s more recent past. But Seville is getting even hotter and new urban interventions are required. In May, the city recorded three consecutive days with temperatures of over 40c for the first time on record – proof that human-driven climate change is ratcheting up the heat in a city already known as the “frying pan of Europe”. By 2050, it could see summer highs of 50c and an estimated 20 per cent reduction in rainfall, a deadly combination for its metropolitan population of 1.5 million people. In July 2022, when the mercury topped 42c for several days, 132 people died as a result of the temperature.

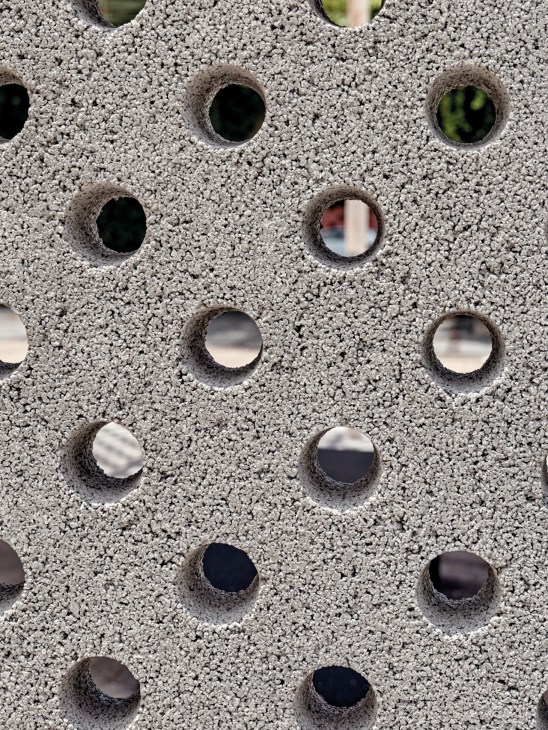

As a consequence of these challenges, Seville, which is home to world-leading experts on extreme heat, is leading the charge when it comes to innovative climate-mitigation strategies. At the forefront of this mission is a sleek underground chamber that’s filled with what resemble dozens of metal air ducts. These are qanats, subterranean aqueducts that have been used since the third century bce to improve irrigation and lower ambient temperatures.

We are at the Cartuja Qanat development, a council project overseen by the University of Seville, that is channelling the city’s Moorish past to help solve its modern ills. Qanats became widespread in the Middle East because of their effectiveness in diverting rainwater from higher altitudes to semi-arid land, where it could be used to irrigate crops or provide drinking water for animals. “We’re using the ancient Persian qanat idea to create a 21st-century version,” says María de la Paz Montero Gutiérrez, a researcher on the project. Seville’s modern qanats snake through buildings and energy infrastructure, where their metal surfaces emit cold air that has been found to lower ambient temperatures by between 8c and 9c. The ducts converge at what was once the site of Seville’s 1992 World Expo. Montero Gutiérrez says that councils from across Spain have come to the city to learn more. There are plans to expand the qanat system across the river and into Seville’s city centre.

Another project that aims to increase Seville’s water supply and harness its potential for temperature regulation is the Life Watercool scheme. This EU-funded project creates channels that collect, store and pump water run-off into public spaces. It is leading the transformation of Seville’s Cruz Roja Avenue in the city centre from a traffic-choked thoroughfare into a shaded pedestrian zone dotted with water features designed to provide respite for citizens and visitors during the sweltering summer months.

While Cartuja Qanat and Life Watercool focus on infrastructural heat mitigation, Prometeo Sevilla is concerned with the psyche. In 2022 the city became the first in the world to name and categorise heatwaves – a policy anointed when Heatwave Zoe struck in July that year. The programme’s aim is to raise awareness of these increasingly common extreme-weather events. “The idea is simple,” says José María Martín-Olalla, professor of physics at the University of Seville and a Prometeo Sevilla spokesperson. “It’s the same reason why they give names to more adverse winter-type phenomena – so that people take certain precautions.”

The programme’s team is made up of university faculty and climate scientists from the Arsht-Rock Resilience Centre. Their job involves identifying future heatwaves, naming them and then communicating the attendant risks to the city council. But while the naming part has proved effective in helping people to remember them post-facto (early studies show that a third of participants remembered named heatwaves over unnamed ones), the work is complicated by differing definitions about what constitutes such an event. “If you’re talking about a hurricane, you see the eye of the storm,” says Martín-Olalla, explaining that the classification of extreme-heat events differs even within Spain. “A heatwave in Seville isn’t the same as one in Bilbao.” In the former, temperatures must exceed 40c for three consecutive days, while in the cooler, greener north of Spain, where average summer temperatures hover near 20c, the threshold is less rigid, though it would almost certainly be lower. The challenge is to educate Sevillanos on how to react so that the now traditional summer heatwaves do not necessarily lead to loss of life. In this way, the city could help to educate a warming world about how to cope with higher temperatures.

Facing up to these challenges doesn’t just involve large-scale planning. Seville also deploys more discreet measures that allow people to go about their day in comfort. Municipal councils open up public libraries, schools and sports centres when it’s particularly hot so that locals can take advantage of on-site air-conditioning systems. In the city centre, roads such as Calle Sierpes and Calle Tetuán are covered by awnings hung between buildings that allow shoppers to move along the grand, polished-stone streets beneath a layer of shade. In the bohemian Alameda district, as the sun begins its daily descent, the heat lingers. In one plaza, locals sip cañas and smoke cigarettes in the shade. Then, all of a sudden, tiny metallic water jets hidden in the square’s many parasols hiss into life, emitting a thin, glittering mist. By 20.00, though the mercury is still showing 27c, the atmosphere has cooled and young and old have begun their twilight perambulations. This city, so used to heat, is getting used to heat mitigation too.

Three ways to cool down your city

Let buildings breathe

In Abu Dhabi, new buildings draw inspiration from traditional mashrabiya screens to ventilate naturally, while Copenhagen mandates green roofs on its new builds.

Plant more trees and get residents involved

Freetown in Sierra Leone has launched “Freetown the Treetown”, a programme that pays residents to plant and monitor trees and mangroves, engaging the community in a restorative activity.

Build in cooler colours

Black absorbs more heat than other hues, so why not change the colour of asphalt in cities? There’s a reason why residents of Greek islands have long whitewashed their buildings.

14 summer shoes that are more than just a fashion statement

Stylist: Kyoko Tamoto

For style inspiration, men should look to women’s wardrobe staples – from handbags to high-waisted trousers

According to a study by the Centre for Retail Research, thieves target items based on factors such value, uniqueness and desirability. These factors explain why singer Wes Nelson’s Louis Vuitton bag was recently stolen on a train and the Gucci bags of both former pop star Kerry Katona and Kristi Noem, the US Department of Homeland Security secretary, were nicked. At the height of summer, when the streets of Rome overflow with tourists carrying Fendi Baguettes and the Croisette in Cannes is filled with women toting Hermès Birkins, criminals work overtime. The common thread? Handbags – and not just their contents – are hot commodities.

Could the recent failed theft of my man bag while I was travelling to Italy indicate that the style is becoming as big of a hit? I had owned the black cross-body for less than a week and was already enamoured of it, so the theft attempt only added to my hunch that I was onto something. Did I mention that I fought off three would-be muggers?

I was inspired to buy it after seeing Los Angeles-based musician Role Model toting a Miu Miu Aventure bag in his “Sally” video clip earlier this year. I soon couldn’t get enough of the fact that I no longer had to stuff my pockets with keys, sunglasses and a wallet. My unsightly trouser bulges disappeared and I had room to carry moisturiser and cologne too. This is especially handy in the summer months, when enjoying a sense of freedom and lightness feels more important than ever.

The bag also adds to my look. The one that I chose is a technical number from Japanese brand Milesto, which leans towards the functional (in terms of aesthetic, think outdoor brands such as Snow Peak and Arc’teryx). But the pleasure that using it has given me has made me think that I might need to start building a full collection: a casual JW Anderson Bumper for walks around the city; a black Loewe Puzzle for playful nights out; a Saint Laurent Sac du Jour Nano tote for when I’m feeling professional. I now want man bags in

a variety of styles, colours, sizes and materials – leather, canvas, nylon – the works. I’m even dreaming of starting a support group called “Blokes with Birkins”, in which members gather to talk about how fellas without man bags don’t know what they’re missing.

I’m aware that for most women (and a few clued-in men) the joy of carrying a well-made handbag isn’t news. But this certainly feels like groundbreaking territory for men. I have plenty of male – admittedly pretty blokey – friends who still laugh at the concept of the man bag and need convincing.

This got me thinking: what other items are staples in women’s wardrobes but only adopted by a small number of men? What else am I missing a trick on? Wearing necklaces isn’t groundbreaking (thanks to octogenarian Italian men wearing their crucifixes and Paul Mescal’s famous chain). I can see that ruffled shirts are having a moment but they aren’t really for my slight frame and neither are leggings.

The opportunity, perhaps, lies in high-waisted trousers. These mostly disappeared from men’s wardrobes in the 1960s but this summer I’m considering grabbing a pair of linen Gurkha trousers that will define my waistline and visually lengthen my legs. Fisherman sandals, normally the preserve of schoolboys and a summer wardrobe staple for women, are no longer a laughing stock, thanks to the popularity of brands such as Birkenstock. I’m thinking of going for the interwoven leather straps of Grenson or Paraboot, which are ideal for both casual and formal environments. My only concern is that a tasteful thief will try to steal them – but they’re not getting them without a fight.

A look inside Elizabeth Byng and Craig Cohon’s getaway retreat where family comes together

For New York-born literary agent Elizabeth Byng and Canadian entrepreneur Craig Cohon, building a holiday house was a significant step: though the couple had been together for close to nine years, they had not yet shared a house. Kairos was a way of making a permanent commitment to each other.

“The whole design was centered around the idea of the house as a meeting place,” says Cohon. Byng agrees. “We don’t have a child together so this is our joint creation and a place where we can gather our friends and all of the different parts of our family,” she says.

With children from previous relationships aged between 13 and 26, and split between London and New York, convening loved ones can be a logistical challenge. “But when it works, it’s magical,” says Cohon. Byng and Cohon chose the Cycladic island of Antiparos after visiting a friend who had set up home there. They settled on a spot on the cooler, eastern side of the island and passed on their brief to London-based Studio Seilern Architects. In 2021 builders began work on the home, which was completed last summer. “Watching our children’s faces when we showed them our place for the first time was a beautiful experience,” says Cohon.

The main house sits atop a steep hill overlooking the Aegean islands. As the sun arcs into the clear sky, the building’s white limewash is reflected in the still pool water as boats drift by on the sea below. Two guesthouses set into the hillside, camouflaged with cracked brown stones, provide five extra bedrooms. “In the morning, you can hear the sounds of the buzzing bees and the wind blowing in the grasses,” says Cohon. “The colours here are soothing and calm. There’s a herb garden, as well as fig and olive trees.”

Cohon and Byng’s intention was to make the most of the views; to that end, there are three terraces that connect to the top floor of the main house and they also created a path that winds its way to the top of the hill. The atmosphere here is Byng’s favourite aspect of Kairos. “For me, the most luxurious thing about this place is the headspace that it puts me in,” she says.

The couple tell Monocle that one of their priorities was to keep the build of the house – and its contents – as local as possible. The ceramics were sourced from a potter working on a mountain on the island and the marble that was used to make the dining-room table was extracted from a quarry on nearby Paros. A carpenter from the area was engaged to construct some of the furniture, including the mobile bar used for entertaining guests. “We didn’t hire an interior designer,” says Byng. “So it was a learning process. The idea was to blend a contemporary feel with the island’s airy Mediterranean sensibility.” Cohon attributes the beauty of Kairos to the intuitive knowledge brought by the craftspeople who worked on it. “If you go for the local option, you end up with builders who understand the place that they are working in.”

One of the couple’s most cherished features of the property is the built-in amphitheatre, which they use to stage spontaneous performances with family and friends. “We are in Greece, the natural forum for conversation, debate and philosophy, so it was fitting,” says Byng. Describing the creative atmosphere that it inspires, Cohon tells us about a particular summer evening. “There were 14 of us and we were putting on theatrical shows with lights, music, props and staging, and suddenly there was a peal of thunder,” he says. “Soft rain started falling and it was just magical.”

For anyone who might be considering embarking on a similar project, Cohon and Byng have some important advice. “Make sure that you create a thorough brief and really think through how you would like to spend time in the space,” says Cohon. “And hire an architect who really understands and responds to the brief. Go local when it comes to the construction, then step back. Don’t try to control the process.”

Amassa: A bucolic retreat attuned to nature’s gentle rhythms

A commission to restore an old residence or building is tricky enough. But when Bindloss Dawes was asked to take on a project in Gascony, a southwestern region of France, the UK architecture firm was faced with the task of sensitively renovating what was once an entire hamlet – workers’ cottages, bakery and piggery included – and turning it into a wellness retreat.

Named Amassa, the property is located between Toulouse and Bordeaux, and is owned by Tania Eber and Ben Rose, a London-based couple who have had a longstanding interest in Gascony since first visiting and buying a home in the region 20 years ago. For Bindloss Dawes, working with clients with an inside track on local builders made the process of finding the right people – with the right tools – for the job a smooth process. “Craftspeople in France aren’t easily found online – it’s all word of mouth,” Oliver Bindloss, architect and co-founder of Bindloss Dawes, tells monocle. “We relied on a good builder who did all of the masonry and found someone to do the timber for the roofs. The result is various pieces by different tradespeople coming together in one cohesive project.”

Assembling a skilled force of builders and craftspeople, Bindloss Dawes got to work on restoring the stone, timber and clay roof structures of the existing cottages, as well as the addition of new spaces, including two outdoor swimming pools and communal areas for relaxing and dining. “There’s no shortage of ruins around France so builders here aren’t afraid to tackle structural issues, cracks and movements,” adds Bindloss. Once the structures of the cottages were refreshed, Eber sourced traditional Basque designs to furnish the guest rooms.

Central to the project is a 300-year-old stone barn that needed stabilising before a concrete mezzanine level could be added to the space. At its tallest point, the barn is 10 metres high, evoking the vertical architecture of churches. Stone walls half a metre thick also keep the interiors cool. “There’s a monastic feel that comes from the scale of the barn,” says Bindloss. In addition to the concrete intervention, the architects included a west-facing, four-metre-high window that catches the afternoon sun. Here, visitors on Amassa retreats are invited to practice yoga, meditate and even take part in arts and crafts sessions.

For an architect, how does it differ from residential or commercial projects to design a space intended for serenity? “There’s a focus on the rhythm of the day, the different moments for eating, relaxing, exploring. We wanted to make sure that there was a possibility to use the space all through the day.” As such, the barn and its surrounding buildings allow for the beauty of Gascony to take centre stage. “Though we put in new windows and did structural repairs, it almost feels like we’ve done very little. Sometimes the skill of the architect is to make your work invisible.”

amassaplace.com

The most beautiful outdoor furniture for long summer dinners

Whether you want to soak up the sun or cool off with an ice-cold spritz in the shade, Monocle has rounded up the outdoor furniture and terrace-ready homeware that will help you make the most of the season’s long days and balmy evenings.

These chairs, tables, ice-cream cups and more will be perfect accompaniments to brightly coloured apéritifs, tasty tidbits and sizzling barbecues that beckon as dusk descends. Summer is fleeting, so relish every sunny second in style.

Berlingot glasses and carafe

by Laguna B

Italy

Murano-based Laguna B’s striped glasses and carafe will bring Venetian flair to your cocktail hour or table setting.

Embrace outdoor dining chair

by Carl Hansen & Søn

Denmark

For Danish design company Carl Hansen & Søn, Vienna-based design studio Eoos created this supremely comfortable outdoor dining chair that hugs the body’s contours. Made from untreated teak, the chair will develop a distinctive patina over time, making it uniquely yours for this summer season and many more to come.

The Classic table lamp by Lumena for The Monocle Shop

South Korea

When the sun sets but the drinks keep flowing, a little ambient lighting will go a long way. Crafted with precision by South Korean lighting experts Lumena, in partnership with The Monocle Shop, this handy lamp can stand on its own or be unscrewed from its base so that it can be hung like a lantern.

Costa chair by Andreu World

Spain

Andreu World’s Costa chair’s characteristic double-cinched woven seat and backrest beckons, unfussy and unphased, offering the perfect spot to rest even if still dripping from the pool. The fresh and resistant fabric is ideal for outdoor or indoor use so there’s no need to be restricted to one or the other.

Atena side table by Dolce & Gabbana Casa

Italy

Nobody does aperitivo hour like the Italians. Case in point: Dolce & Gabbana Casa, the design and homeware subdivision of the Milan-headquartered fashion house. Its Atena side table, made from gloss-finished wood with a sturdy steel stem, is meticulously polished and pleasingly curvaceous. Drag it out onto the terrace to support drinks and snacks until it’s time for dinner.

Solas café table by Case

UK

British designer Matthew Hilton’s refined café table is the perfect place to perch an icy spritz. The evenly keeled stainless-steel base and teak-slatted tabletop will ensure nothing can topple your summer tipple.

Italian ice cups by Hay

Denmark

Danish design firm Hay’s Italian-made ice-cream cups are worthy of the creamiest pistachio gelato or freshest raspberry sorbet. Constructed from stainless steel with a slim stem and rounded bowl, they’ll have you hankering for a chilled dessert every day of the warmer months.

hay.dk

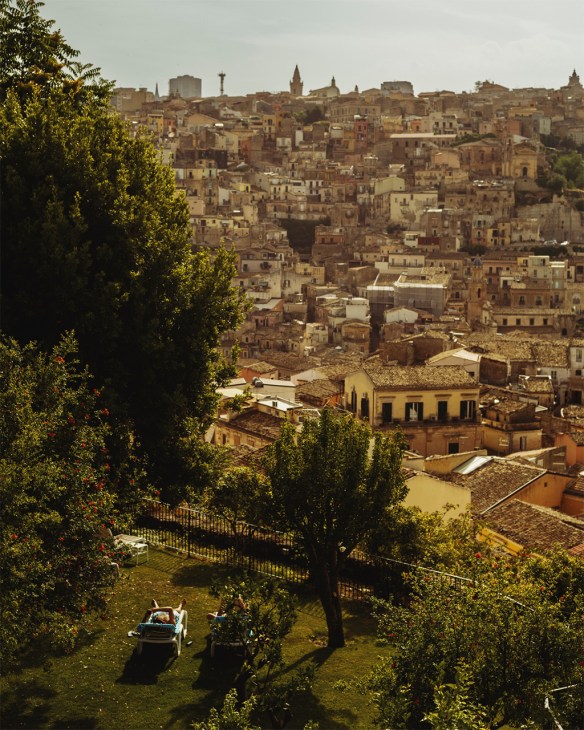

Sicily’s ‘scattered hotels’ offer new hope to the city’s hospitality industry

“There’s this building, the one behind it and the one with the balcony over there,” says Michele Bitetti, standing on a terrazza in the Sicilian town of Ragusa. He’s pointing out various parts of his hotel, the Giardino sul Duomo, to monocle – which might not sound like a particularly challenging task, except that this is an albergo diffuso (“scattered hotel”). That means the hotel’s 16 rooms are dotted around this beautiful neighbourhood. Ten years ago, the buildings that now house them were abandoned, symptoms of a depopulation trend that has hollowed out communities across the Bel Paese – a consequence of mass emigration, declining work opportunities and a plummeting birth rate.

In Sicily, these factors have dramatically converged and entire villages in the interior of the Mediterranean’s largest island have been boarded up. In the region’s more prosperous coastal areas, piecemeal losses have led to scatterings of abandoned buildings, giving towns a gap-toothed look. This was the case in Ragusa, many of whose citizens had left the old town (known as Ibla) either for the new suburbs that climb vertiginously up the opposite hill or for a new life across the ocean. At around the same time that Giancarlo dall’Ara, a young hospitality consultant from northwestern Italy, devised the albergo diffuso concept as a way of reviving tourism in the Friuli-Venezia-Giulia region, the regional government passed a law that provided funding and tax breaks to anyone starting a business in Ragusa or Siracusa.

This is what enabled Bitetti and his family to begin developing some buildings around an ancient garden into Giardino sul Duomo. Neighbours were initially resistant, wary of the effect that an influx of tourists might have on that perennial urban issue of parking. But, as Bitetti puts it, “Now they are grateful because we have renovated their neighbourhood and their houses are worth something.” For tourists attracted to the autonomy of private rentals, but who still appreciate the service provided by more traditional hotels, the albergo diffuso offers a middle way. “If people start to come back and those who already live here begin to renovate their homes, the story changes,” says Bitetti. “It’s a virtuous circle.” There are currently about 150 alberghi diffusi in Italy. At a time when hundreds of communities are facing extinction due to depopulation, such businesses are breathing new life into these beautiful villages.