The Forecast

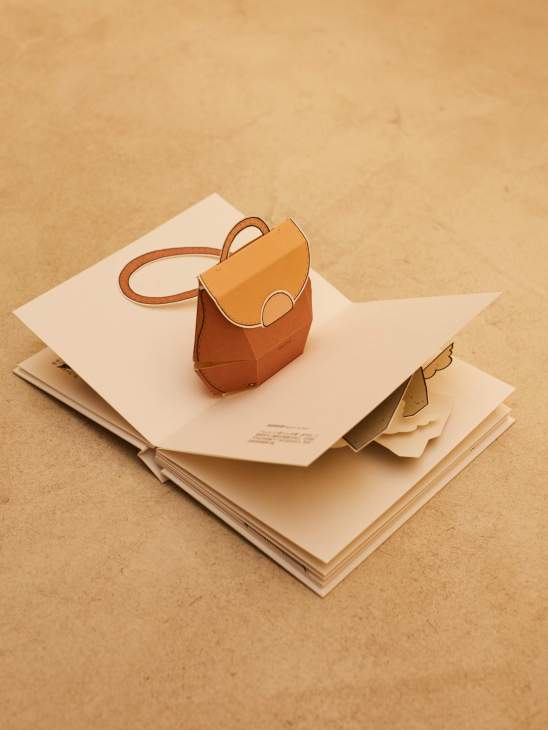

Hide and sleek: How Polène quietly took over the contemporary handbag market

On Paris’s Rue de Richelieu, nothing marks the start of the day more clearly than the queue forming behind the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. These are not library-goers, however; they are shoppers waiting for the doors to open at French handbag brand Polène’s flagship boutique. By 10.00, the start of the shop’s business day, a considerable line has appeared, with more eager customers, mostly from the US and Japan, joining throughout the day. It’s a similar scene at the label’s New York flagship on Broadway and, judging by the number of shopping bags that people leave with, the company has fostered a committed client base worldwide.

The reason behind the insatiable customer appetite? Polène bags have all the hallmarks of luxury – artisan-made, produced in limited quantities and sold in sleek standalone boutiques across the globe – yet they retail at prices ranging from €330 to €520.

Polène was established in 2016 by siblings Elsa, Antoine and Mathieu Mothay, the great-grandchildren of the founders of the Normandy cult label Saint James. It is part of a wave of leather-goods brands filling a gap for competitively priced, high-quality bags with a designer sensibility. As the cost of luxury handbags by heritage brands has risen by up to 85 per cent in the past five years, these contemporary makers offer a compelling alternative, with production and sourcing standards that rival those of their premium counterparts.

All of the leather used by Polène is Spanish or Italian calfskin, with a dedicated quality development team travelling to Italy every two weeks to ensure consistency. Every bag is then crafted in small batches in the Andalusian leatherworking town of Ubrique, where Loewe also makes a lot of its hide accessories. The meticulous process, from initial sketch to finished product, takes at least 18 months and involves a team of 2,000 artisans – a long way from the 10 that Polène started with less than a decade ago.

“At a time when luxury-goods prices have reached an all-time high, we’re seeing an increased demand for contemporary bags,” says Sourcewhere founder Erica Wright, whose platform is dedicated to finding rare fashion items and servicing high- end shoppers’ requests on a one-to-one basis. “Consumers are seeking classic designs that evoke a sense of heritage and longevity in what is now an oversaturated market. They invest in these pieces as they would in a vintage luxury bag.”

Within a similar price range to Polène, Wright highlights Manu Atelier from Istanbul and Demellier from London – alongside the pricier Swedish label Toteme – as being particularly sought-after on her platform. Similarly, Kate Benson, the buying director at e-commerce giant Net-a-Porter, observes that these contemporary brands “have asserted themselves as wardrobe heroes”. The numbers speak for themselves: since August 2024 the website has seen a 300 per cent increase in searches for black Toteme bags and a 100 per cent increase in searches for pieces by Demellier.

The resurgence in the contemporary handbag market has also caught the attention of major investors. This summer, Bernard Arnault’s private equity firm L Catterton – which also has shares in apc, Ganni and Birkenstock – acquired a minority stake in Polène. The investment comes at a pivotal moment as sister group lvmh, whose portfolio focuses on premium fashion and leather goods, reported a 5 per cent drop in revenues in the third quarter of 2024 – the first decrease in years. This affirms the market shift – and suggests that we will be seeing a lot more of affordably priced brands like Polène in the coming year.

Though the company performs well online through its e-commerce platform, it has big plans for bricks-and-mortar retail in 2025: in addition to its existing locations in Paris, New York, Tokyo and Seoul, new Polène boutiques will also be opening in London, Copenhagen and Hamburg. An additional location on Paris’s Champs-Élyéees is also in the works.

This focus on directly operated retail has been a big part of its formula for success. Aside from its corner in lvmh-owned department store Le Bon Marché in Paris, Polène doesn’t work with other retailers – thus ensuring that its team has full control of the customer experience, including interior design and staff training. In fact, every element of the Polène shopping journey is thought out to feel as elevated as possible, from the architect-designed interiors by Valériane Lazard to the staff’s stylish, all-beige uniforms.

What also sets these smaller brands apart is that they are less bound to the fashion calendar. Instead of producing seasonal collections, Polène releases new designs only when the team is fully satisfied with them. That’s why its line-up remains relatively concise, currently featuring 13 models available in various sizes and colours. Its debut design, the Numéro Un top-handle bag, remains among the bestsellers, along with the half-moon-shaped Numéro Dix and the Numéro Huit bucket bag.

Thanks to the consistency in their designs, many of these contemporary handbag brands now enjoy a level of recognition comparable to that of well-trodden luxury names. Among the best examples is apc, which has become just as renowned for its maroquinerie as for the clean-cut denim it has been crafting since 1987. Its leather offer took off in 2017 with the launch of the Demi‑Lune – a rounded, cross-body bag that quickly became one of the brand’s best-known pieces. Today the company generates 40 per cent of its revenue from handbags, compared with 25 per cent in 2017. Like Polène, apc keeps logos small and understated; yet many of its designs have achieved the icon status that its luxury competitors continuously strive for. “People want to buy less but go back to quality and durability,” says apc founder Jean Touitou. “They’re getting tired of fashion as a sign of social status and are no longer looking for big luxury labels that are branding themselves too much.”

There’s also more public awareness around the high mark-ups of luxury goods. In an industry where pricing is often decided by prestige over production costs, customers are increasingly unwilling to pay a premium for a name. This has sparked a growing desire among consumers to be part of something smaller. For brands such as Manu Atelier, this sense of intimacy is part of the appeal. Its founders, sisters Merve Manastir and Beste Manastir Bagdatli, were born into one of Turkey’s most prominent leatherworking families and wanted to bring their craft to the world when they started the brand in 2014. Though its items are sold by more than 90 retailers globally, including Net-a-Porter China, Merve and Beste’s company is a family business in the truest sense, with their father training the artisans they collaborate with.

The sisters favour hand-stitching over machine production. “Customers feel that they are investing in something meaningful, personal and less mass-produced,” says Merve. “This level of hands-on expertise is rare in a world where many brands are scaling up production and outsourcing craftsmanship.” The firm also aligns well with concerns around sustainability, using leftover material for bag linings or upcycled collections.

While most contemporary leather-goods brands are aimed at women, there are some men’s equivalents shaking up the industry. Bennett Winch has become a go-to for made-to-last weekender bags, briefcases and backpacks, guided by a simple ethos: buy well and you need only buy once. Its bag sales now stand at 8,000 a year, in part thanks to an impressive list of 49 worldwide stockists. The Savile Row-based brand has carved out its own niche: competitively priced bags (starting at less than €1,000 compared with the average €2,500 at which similar products by heritage brands start) designed to be kept for ever thanks to a free lifetime-repairs service.

Yet the demand for independent bag brands is not simply about customers wanting to spend less for the same quality, according to the label’s co-founder Robin Winch. “They are looking for that value proposition beyond the price point,” he says. “Many of our customers could afford big names but their purchases are driven by their beliefs: they have become disconnected from conglomerates.” This new wave of accessories specialists are here to offer an alternative in a competitive market – and change handbag economics for the long term. — polene-paris.com; manuatelier.com; bennettwinch.com

Three more contemporary bag brands to watch in 2025, according to Sourcewhere’s Erica Wright

1.

Savette

New York-based designer Amy Zurek dreams up “Made in Florence” women’s bags that blend modern and classical aesthetics. Look out for the Florence top-handle style and Tondo tote bag.

savette.com

2.

Fane

Launched in 2020 by Laurie-Anne Braun and Margot Baudequin, Parisian label Fane makes logo-free shoulder bags using sustainable production methods and the finest Italian and French leathers.

faneofficiel.fr

3.

Neous

Vanissa Antonious’s London-based label excels in meticulously crafted handbags. All designs are inspired by minimalist architecture, so expect sleek, clean silhouettes.

neous.co.uk

Three cities you’ll want to move to in 2025

In recent years, many people have been searching for a step change. Much of this, no doubt, has been driven by significant global events (the dreaded “P” word comes to mind), which reframed the meaning of home and redefined what we expect from the cities we live in. In the US, for instance, research by Goldman Sachs has found that Americans are moving away from bigger metropolises, lured by the relaxed pace of smaller centres.

Many reports have linked these relocations to the search for a slower lifestyle. But this shouldn’t necessarily be – and isn’t – the driver for all such shifts. Those looking to progress their careers, for instance, might want to move to an industry- specific hub. Change might also be driven by the search for inspiration – perhaps a culture-rich conurbation might broaden one’s horizons and inspire new creative works. Or it might simply be driven by a desire to return to a particular landscape, to mountain towns and coastal resorts alike.

Whatever the catalyst, moving to a new city can encourage you to escape your comfort zone, search for new opportunities and find a community that resonates. Here, we offer some suggestions that might help you find a new place that perfectly suits your personal tastes.

1.

Move here to start a business

Tirana

Albania

In Tirana, a warm welcome is government policy. “If most countries suffer from xenophobia,” the Albanian capital’s mayor, Erion Veliaj, tells monocle. “This one has xenophilia.” It’s an affliction that’s immediately evident on the city’s sun-soaked boulevards and one that has also made it onto the statute books. As countries elsewhere in Europe turn inwards, introducing more restrictive entry requirements, Albania continues to court newcomers with attractive tax breaks and residency permits. Under its unique permit scheme, which has no minimum-income threshold, immigrants receive a one-year visa, renewable up to five years, in return for proof of a contract with a foreign company.

Belgian architect Guust Selhorst moved to Tirana in 2017 to work on the redesign of Skandabeg Square, the city’s vast communist-era plaza. “When I told my mum I was going to Albania, she was not so excited,” he says, squinting in the November sun. “She had only heard about the country in a negative way.” When he arrived, Selhorst soon realised that stereotypes concerning lawlessness were wide of the mark. “It’s rare to experience criminality,” he says. “When I lived in Brussels, many colleagues were robbed at knifepoint. That would never happen here.” But it was more than just a low crime rate that kept him in Tirana. Selhorst recognised that the city was ripe for entrepreneurialism, especially in the architectural sector. After convincing his Belgian employers to open an office, he later set up his own practice, as well as a landscape architecture firm. “I saw that with all the new buildings there was need for a landscape designer,” he says. “At the same time, there was a new landscape- design faculty at the public university. Its students have now graduated and I’ve hired some of them.”

Given that businesses don’t pay tax on their first €140,000 of revenue (and only 15 per cent after that) and are required to contribute a fraction of the employee-related taxes expected elsewhere in Europe, going it alone is an enticing prospect. Tirana’s university sector and growing ties with Italian institutions attracted Roberto Mazzuca here to study dentistry. While a student, he began letting out vacant properties to fellow Italian expats. After graduating he started a company that now manages dozens of properties across Tirana. “It’s difficult to start a business in Italy today,” he says. “Everything already exists and the taxes are high.”

For many years, the enduring image of Albania, especially in Italy, was of The Vlora, a cargo ship that landed in Bari in August 1991 with about 20,000 refugees on board who were fleeing the chaos that followed the collapse of communism in the Balkan nation. In the past 10 years, the same number of Italians have moved in the opposite direction, seeking opportunities and a higher quality of life in a country where the economy grew by 3.3 per cent in 2024. “They speak Italian here and we support the same football teams,” says Mazzuca. “I say that this is like another region of Italy.” Tirana Airport has more connections to Italian cities than any other hub outside of Rome or Milan. Veliaj cites the case of an Italian minister who regularly spends weekends in the Albanian capital because it is so cheap. “It costs about €25 to get here and you can stay in a nice hotel with a spa for €65 to €75 off-season. Eat and drink like in Italy, for a third of the price.”

Of course, with an increase in the number of newcomers, those low prices have begun to creep up. “When I arrived, I’d pay €250 a month for an apartment,” says Selhorst. “That same apartment today would be €550.” However, he adds, “The city has more to offer than it did 10 years ago.”

Tirana’s bar and restaurant scene is thriving, thanks to new openings such as Destil Creative Hub, which houses art and a recording studio, as well as stalwarts such as Radio Bar, where the cocktail menu rivals any New York or Berlin establishment. The pace of change is exhilarating. “Most mayors are in charge of preserving things,” says Veliaj. “Our job here is to change everything.” If Tirana’s citizens remain xenophilic as its streets continue to swell with new faces, his will be a job well done.

Three other smaller cities in which to launch your business

1.

Salt Lake City, USA (population: 200,000)

Tech entrepreneurs are flocking to Utah to take advantage of the state’s highly educated workforce. On top of that, Salt Lake City has access to some of the finest natural landscapes in the US, including great ski slopes within a few hours’ drive.

2.

Lyon, France (pop: 520,000)

With a significantly lower cost of living than Paris, Lyon’s beautiful residential and retail property stock could provide the perfect base from which to launch your business. It also has some of the best food you will find anywhere in the world.

3.

Muscat, Oman (pop: 1,676,000)

At the crossroads of the Middle East, North Africa and southern Asia, Muscat’s business regulations are nuanced and advantageous. With a governmental certification on offer for export industries, this ancient city is a good place to manage global supply chains.

2.

Move here to capitalise on a hospitality boom

Essaouira

Morocco

It’s easy to fall for the considerable charms of Essaouira, a storied port town perched on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. Less frenetic than Marrakech or Fez, and with a Unesco World Heritage listing that’s partly attributable to its rich history of religious coexistence, the city has long appealed to adventurers, artists and bohemians. During the 1960s it had a hippy reputation and Jimi Hendrix was among its famous visitors. Since the 1990s it has become a popular destination for a wider range of holidaymakers and investors while maintaining more of an off-the-beaten-track vibe than other Moroccan coastal resorts.

Filmmakers adore the town – its evocative architecture has featured in several movies and Netflix series. It has also become a firm fixture on the surfing circuit recently, due to its favourable winds. Digital nomads flock here, attracted by the laidback atmosphere and year-round balmy temperatures. Music festivals – particularly a renowned annual event that focuses on Gnawa, an electric blend of traditional Berber, African and Arabic sounds – and other cultural offerings ensure that the town feels lively throughout the year. Unesco director-general Audrey Azoulay comes from a prominent Essaouira family and is sometimes seen walking its long sandy beach.

Morocco’s cet time zone makes it very convenient for European business, in particular, and the reasonably cheap cost of living has long drawn French entrepreneurs who appreciate the bilingual (French and Arabic) culture and low-cost direct flights from Paris and Marseille. Other investors include British, German, Italian and Swiss expatriates, many of whom have swapped jobs and homes to settle here, often buying 18th-century riads that they turn into guesthouses. According to one researcher, close to 400 properties in Essaouira’s old quarter are owned by foreigners.

Emma Wilson traded her life as an interior designer in London to establish Castles in the Sand, a bespoke rental business anchored in a pair of 200-year-old local residences – Dar Beida and Dar Emma – which she renovated from scratch. Her advice to those considering a similar move? “Follow your heart and go to Essaouira because you love it, not for financial investment,” she says. “There is a lot to learn; acceptance and respect are key. Always use a notary and make sure things are done legally.” Alyson Huggett moved to Morocco two decades ago and founded Essaouira cookery school Folklore Collectif, which highlights traditional cuisine, in 2022. She says that making her home here has been a positive experience. “Always seek professional advice and have up-to-date information as a foreigner,” she says. “This is a fast growing and stable economy within a stable kingdom but laws around requirements and imports need careful planning and consideration, as is the case anywhere.”

As elsewhere in the world, there are grumbles about gentrification and the challenge of balancing local and foreign investment. Zakariya Azzahir, owner of Yalla Surf watersports school, grew up in Essaouira and recommends that investors focus on sustainable businesses. “The town has a strong connection to traditional craftsmanship and eco-conscious tourism,” he says. “Investments that respect and preserve Essaouira’s unique heritage – such as eco-lodges, surf schools or small-scale community-focused hospitality projects – usually work well.”

Like others, Azzahir advises prospective residents and investors to spend a few months getting to know the local community before making the move. “Essaouira has taught me the importance of patience and adaptability,” he says. “The lifestyle here is slower and more deliberate, and that’s something to embrace rather than fight. I’ve also learnt the value of building relationships with visitors. In Essaouira, business often flows through word of mouth and trust is built over time. It’s a place where people value authenticity. That has been a rewarding and humbling experience for me.”

Three other small cities in which to open a hospitality venture

1.

Hobart, Australia (population: 55,000)

Hobart has clean air, prime produce and great taste. Rodney Dunn and Séverine Demanet’s beloved Agrarian Kitchen restaurant, cookery school and farm is a mainstay – and only an hour outside the city.

2.

Porvoo, Finland (pop: 51,000)

An hour or so from Helsinki, surrounded by fertile farmland and home to a budding new restaurant scene, Porvoo is offering a rather charming update on the New Nordic way of eating.

3.

Charleston, USA (pop: 155,000)

The tables are turning as the city’s star rises in the restaurant stakes, but there’s still some vacancy for a nice independent hotel or daring little diner. The port’s charming cobblestone streets and antebellum houses aren’t the only draw – the food scene is attracting talent from all over the US.

3.

Move here to work with your hands

Port Townsend

USA

A fine layer of sawdust coats monocle’s boots as a fitting souvenir from Port Townsend. The small city swells to the gills every September for North America’s largest wooden-boat festival, founded in 1977. Boat owners from up and down the West Coast cruise into this picturesque marina in north-west Washington to show off their lovingly restored vessels. Though there are many larger harbours on the Pacific coast, people come to Port Townsend because it has a reputation as the premier port for wooden boat design, build and restoration. All that hammering and sawing can make a racket, so the festival’s host, the Northwest Maritime Center, does something clever. It works with the town’s estate agents to identify the newest residents (about 150 move here annually) and invite them on a behind-the-scenes tour to inculcate respect for their adopted hometown’s traditional crafts.

“We care about relationships and human scale,” the centre’s director, Jake Beattie, tells monocle, describing various civic campaigns to keep chain stores out of downtown. “The culture of craft keeps us small but punching way above our weight for amenities.” New residents are drawn to this 10,000-strong peninsula outpost – about two hours by ferry from both Seattle and Victoria, British Columbia – by the temperate climate, easy pace of life, vibrant main street and growing food-and-drink scene. But to truly embrace living here, pick up a chisel or saw. In addition to a thriving industry for maritime trades anchored by a city-owned boatyard, there are schools dedicated to wooden boatbuilding, fine woodworking and shoemaking. Five master bowmakers call Port Townsend home, the largest concentration in the world, attracting apprentices who have set up their own studios both here and abroad.

In short, working with your hands is this small city’s signature. That culture drew Tucker Piontek, an industrial designer by training, who had a steady career in stop-motion animation at renowned Portland-based studio Laika. He enjoyed designing puppets for the studio behind Hollywood hits including global success Coraline and Tim Burton’s Oscar-nominated Corpse Bride, but sailing is his lifelong love. He enrolled in the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding and graduated in 2017. With a plethora of jobs available here, from restoring historic wooden yachts to fabricating aerospace parts, it was easy to stick around after graduation. Three years ago he returned to the school as an instructor. “You have to want to live here; it’s an end-of-the-road kind of place,” he says, while on a break before his afternoon class on shipwright drafting, where students draw plans for boats by hand. “Everyone is from somewhere else and has a story about how they ended up here.” In his case, the embrace of craft was the primary draw but the town’s natural beauty and cultural richness make life well-rounded. “I wake up to the sunrise over the Cascades mountains and watch the sun set over Vancouver Island,” he says. Though he no longer works in the film industry, he can still catch arthouse flicks and festival-circuit picks at the Rose Theatre, a well-restored bijou cinema built in 1907. Other residents swear by the city’s live music scene.

Steps from the theatre, pub-goers leave their e-bikes unlocked, an unthinkable prospect in larger North American cities. Along the downtown high street, shops sell books, furniture and records. The town has two newspapers, a radio station and a poetry press. Recent openings include a typewriter shop and a design brand’s flagship retail outpost, as well as a natural-wine bar and off-licence at the Victorian-style Bishop Hotel. The hotel’s new husband-and-wife owners credit some inspiration for buying the place to Finistère, which opened in 2017 and put the city on the map for destination dining. Deborah Taylor helms the kitchen, drawing on her experience at Michelin-starred restaurants in New York. “Port Townsend has a kind of vortex that sucks you in,” says general manager Scott Ross, before turning to greet regulars settling in for happy-hour oysters on a Friday evening.

Three other small cities where you can work with your hands

1.

Inegöl, Turkey (population: 300,000)

Nearly 50 per cent of the land within Inegöl’s boundaries is forest and it has become a centre of excellence for woodwork, especially furniture. Some 2,000 manufacturers and 40,000 people work in the industry.

2.

Ninohe, Japan (pop: 29,000)

This small Japanese city is home to the world’s largest concentration of domestic lacquerware manufacturers. Come for the beautiful decorated bowls and cups, and stay for the fine food and lovely countryside.

3.

Nový Bor, Czechia (pop: 11,400)

North Bohemia, particularly Nový Bor, has been renowned for glassblowing and making since the 17th century – a reputation now enhanced by the city’s School of Glass Art and Design, which has about 400 students.

Interview: Natira Boonsri, Central Group’s CEO, on the Thai retail giant’s future

The future of the department store has been repeatedly questioned over the past decade as luxury brands invest in their own shops and consumer behaviour evolves. But while relationships between brands and department stores might be forever changed – brands are seeking more control and now operate their own concessions within these institutions – department stores will continue to play a critical role in the luxury ecosystem.

Since 2011, Central Department Store Group, which is based in Thailand, has been buying up the best department stores across Europe, from Rinascente in Italy and Illum in Denmark to Selfridges in the UK. While these blockbuster deals have been making international headlines, the retail giant with a magic touch for turning around legacy retailers has also been quietly transforming its own crown jewel, Bangkok’s Central Chidlom. After an extensive renovation led by British architect John Pawson – the largest since it opened in 1973 – the store is due to reopen in December 2024. It will operate mostly on a concession model while acting as a social gathering space, and will focus on servicing the vip customer’s every need. Central Chidlom is now also home to 60 restaurants and cafés.

Natira Boonsri, the ceo of Central Department Store Group and a member of the mighty Chirathivat family that controls Central Group, has spent almost her entire career in department stores. She is currently overseeing 76 locations and has big ambitions for Chidlom, reflecting Thailand’s ever-increasing strength as a luxury market. Here, she tells monocle what’s new and explains how the flow of expertise and information between the group’s Asian and European businesses is positioning Central Group’s retail arm as a global market leader.

How does Chidlom in Bangkok compare to the Central Group’s department stores in Europe?

When we discuss our group’s luxury portfolio, we say that Rinascente is the store of Milan and Selfridges is the store of London. We want Chidlom to be the store of Bangkok. Each one has a different positioning but we want them all to cater to premium customers and be social gathering places.

How has your overseas business influenced the strategy behind the Chidlom renovation?

Some of the businesses are very good at activating the store – what we call retail as media. Rinascente often changes the shop’s façade and lets brands take over the inside to advertise or communicate to customers. We want to do that at Central Chidlom. We have also doubled the space of the Chidlom beauty floor. Selfridges has a very strong beauty offering and it always has new-to-market exclusive launches to create excitement for customers.

How important are VIP customers?

They are instrumental to Chidlom’s success. We have about 7,000 top customers and on average they come almost twice a month and spend 600,000 baht [€16,000] a year, which is very high. That’s why I created the Cenfinity loyalty programme last year. We want to step up a few notches and go beyond expectations. In the past we didn’t have all of the luxury brands that these customers were looking for, so they would have to go elsewhere.

What kind of conversations did you need to have with the luxury brands to convince them to partner with you?

During the coronavirus pandemic we saw a huge spike in luxury consumption in Thailand and we couldn’t ignore it. We shared our vision and renovation project with the luxury brands and they were interested. Most of the fashion brands on the luxury floor are new to Chidlom, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada. Usually they are in shopping malls where they have large boutiques. This is the first time that they have joined a department store in Thailand.

How do you see the overall department-store concept faring in the future?This year we will have medium, single-digit growth, which is considered quite good. Our recently renovated stores are outperforming the others by a long way. When we renovate, we introduce new programmes and lifestyle elements that encourage customers to visit, have a coffee and stay longer. We renew the brand line-up and introduce new ones to the market. We also see an uplift in sales when we redesign the floor layout and make our stores easier to navigate. The department-store model will continue to grow as long as it adapts to the changes in customer behaviour.

How do you see technology affecting the customer experience?

Social commerce has become very successful during the pandemic. Our sales associates would contact our customers using the Line messaging app and send them pictures and videos of new products that they could buy. This remains popular and we want to push it even more – alongside live commerce, where China is very strong. It’s still the start of this journey and we will be slowly growing the digital part of the business.

Will bricks-and-mortar shopping stay at the core of the business?

It’s very important and it will always be there. Customers of every nationality long to have a community hub where they can mingle and hang out with friends.

Are you optimistic for 2025?

The global economy is volatile but Thailand’s gdp is forecast to grow about 3.5 per cent next year. We think we will continue to achieve our targets and see a big growth opportunity in international shoppers. Tourist spending in our stores has already exceeded pre-pandemic levels, even though the number of visitors to Thailand is still below the 40 million who came before the pandemic.

How else do you foresee the Thai retail landscape changing?

There will be about 500,000 square metres of new retail space in Bangkok by 2026 or 2027. Competition is intensifying but that’s good. The more there is, the more everyone wants to transform themselves. That’s better for customers and ultimately it makes Thailand stronger because we’ll be able to attract more tourists.

Loose Ends, the community project turning unfinished projects into heirlooms

There’s a secret digital map of London that even mi5 has never seen. On its glowing surface, hundreds of coloured lights dot the capital. Each represents someone who plays a crucial role in knitting the city together – or weaving, dyeing or crocheting it. That’s because this map shows volunteers from Loose Ends, the originator of the global phenomenon known as “legacy handicrafts”. Its mission is simple and stirring: to deliver the last mile of love.

Loose Ends is registered in Seattle and unlike another local success story, launched by Bill Gates, this one really did start out micro and soft. Knitting is what brought Jennifer Simonic and Masey Kaplan together. From fumbling first attempts at baby blankets to choosing jumper designs for that last university-bound teen, their shared hobby was a constant. And so was a touching story that the two kept hearing in knitting circles.

Whenever their craft community lost a member to death or disability, that person’s knitting basket invariably contained a work in progress intended for loved ones. But for bereaved families, inheriting these unfinished handiworks could be its own sad challenge – what could they do with a confusing tangle of yarn, patterns and equipment? To the trained eyes of Kaplan and Simonic, however, something very different lay in those bundles: a handmade quilt, a cardigan or another poignant heirloom so close to being treasured.

The two friends had an epiphany: that they could link these labours of love with “finishers”, volunteer craftspeople who are eager to complete them. Except for postage and the cost of materials, all work could be done for free. The Loose Ends motto reads, “Started with love by them. Finished with care by us.” Soon, word of the initiative spread. Requests and volunteers poured in. When the Loose Ends brochure appeared in yarn shops, volunteers offered to translate it into Spanish and Swedish, Hmong and Hebrew.

Though Loose Ends began with a focus on knitting, families started asking for help completing everything from English tapestry to Tunisian crochet. Just months after launch, Loose Ends had to retire its original logo. Their original ball-of-yarn design no longer captured its worldwide network, busy not only with knitting needles but also with weaving looms, quilting frames and amigurumi patterns. Today, Loose Ends has 29,000 finishers spread across 70 countries – not bad for a homespun project started barely two years ago. “It doesn’t belong to me and Jen,” says Kaplan. “We co-founded it but we just set the table. Then all of these people started showing up.”

Among them was Olympic diver Tom Daley. The UK athlete became a sensation at the Paris Games when the media caught him knitting between medal-winning dives. The scoop that those reporters missed? Daley had just become a Loose Ends finisher. He even planned to crochet his first assignment during the competition, returning from Paris carrying it in his arms. Instead, he brought home a silver medal. But completing his project soon after (a grandmother’s rainbow blanket, chewed in half by the family terrier), he sang the praises of Loose Ends to his million-plus social-media followers. “They’re a small team doing amazing things,” he wrote. A surge of new volunteers and projects inundated Kaplan and Simonic.

On a recent morning, joining the queen bees of this global fibre-crafts movement, we assumed that we were sitting in the presence of knitting masters. We were mistaken. Simonic, needles flashing throughout our conversation, is asked to unveil her handiwork. “Oh, this?” she says, smirking and holding up the beginnings of a colourful jumper. “Had to rip apart the whole thing. Twice. Par for the course when I knit.”

So which craft is their true speciality? “That’s easy,” says Kaplan. “Matchmaking.” Indeed, like a pair of knitted Sorting Hats, they have matched thousands of carefully chosen finishers with individual heirlooms. Pairing people with projects, they say, requires the right balance of “geography, skill level and druthers”. And perhaps add an abiding trust in human nature.

“There’s a level of divisiveness everywhere these days,” says Kaplan. “Though we never ask about such things, participants who submit a project sometimes bring up their religion and their politics.”

“And their pronouns,” adds Simonic.

“We don’t take any of that into account when making a match,” says Kaplan. “So we’re connecting people who might, under other circumstances, be protesting against each other. But right now, right here? Each of them knows that this person has lost a loved one. So they just think, ‘I know how to knit. I can do this for them.’”

What every crafter understands, they point out, and what cuts through this divide, is that there’s nothing quite like a handcrafted gift. Recipients often speak of a knit or woven present as an embrace, carrying the warmth of the person who started it. It’s little wonder that many crafters facing a health crisis will begin a handmade project for someone close, to comfort that person and themselves. Loose Ends’ mission is to ensure that every one of those gifts reaches the loved one for whom it was intended.

Finishers often put in a duplicate stitch, sometimes easier to feel than see, as a subtle marker. It’s where the original crafter left off and the volunteer’s handiwork begins. Finishers relate how moving it can be, not just to receive a completed piece, but to work on one – transforming what is often an everyday hobby into a profound act.

Charlotte Warshaw, a London finisher, is carefully stitching another family’s heirloom tapestry. Its owner, who was never taught needlepoint, couldn’t finish her mother’s beautiful handiwork nor bear to part with it. So she carried its dangling threads for 25 years until she heard of Loose Ends.

Vintage projects – and this one is far from the oldest – can pose challenges. In this case, neither the pattern nor the yarn colours needed to complete it are still being made. This led to the kind of treasure hunt that is a Loose Ends speciality.

With Warshaw’s ingenuity (and this time without the help of the group’s online forum), yarn collections were rummaged through and matching colours sourced. “Speaking as a finisher, it’s a real honour to be trusted with something like this,” says Warshaw. “It’s not a burden. It’s a gift. This is not one more random scarf I’m knitting. It’s a project that means something.”

Finishers are as varied as the projects that they take on. Meeting them dispels stereotypes about your typical handcrafter. Daley might be Loose Ends’ best-known millennial but he is far from the only one. Interest in fibre crafts, which was growing even before the coronavirus pandemic, became supercharged during lockdown. While other home-friendly activities also flourished, most lost steam once restrictions were lifted. But the boom in handicrafts just kept expanding. According to a study by the Association for Creative Industries, the global crafts market is, for the first time, expected to top $50bn (€47bn) this year. That’s an increase of more than 20 per cent since the height of the pandemic. In another recent study, it found that the largest group of crafters (41 per cent) are millennials.

As many younger consumers question the effects of fast fashion – or just find handiwork cool – granny’s crafting skills are increasingly being embraced by her diy grandchildren. One of them, Elise Craft, more than lives up to her name. “I’m basically an old-time grandma in a Gen X body,” says Craft. From an early age, she picked up knitting, sewing, cross stitch and quilting, finally drawing the line at willow-basket making. But becoming a finisher has been its own kind of learning experience, she adds. “When I opened the email from Jen and read about this project, it struck me that this could have been my own grandmother leaving these quilting squares behind. The more you work on a project such as this, the more you feel a connection to this person who you’ve never met. You sort of form a kinship and feel a real responsibility to preserve the aspects of the original crafter that are in the piece.”

In a rare case for Loose Ends, this quilt is being finished for a finisher. Expert knitter Lynn Richardson, volunteering to complete a complex jumper pattern, suddenly remembered that her family had its own partially done heirloom. It included notes, carefully chosen colours and quilting squares that her mother had started and her father had later saved from going to charity.

The bonds linking project owners and finishers can run deep. “Doing something for someone else, who is grieving, doesn’t mean that the finisher doesn’t feel it too,” says Simonic. “The loss affects both sides.” And so, it seems, does the joy. The jumper that was keeping Richardson’s needles busy belongs to Hilary Krisman. Her mother had worked on it until she died recently, just shy of 100. “It has been transformational,” says Krisman of the richly coloured gift in her hands. “She was so determined that this would be ready for me but, as she got older, her hands became less and less able to continue.” Krisman, who doesn’t knit, remembers thinking at the time, “There must be other people like me in this situation, who don’t know how to get their legacy completed. But who do you turn to?” Then she heard about Loose Ends. Still too emotional to try on her jumper, she can’t stop admiring it. “This will be cherished,” she says. “It will be passed down through my family. This is so wonderful.”

As Loose Ends continues to grow, touching lives across the globe, is there anywhere for the organisation to go but up? Yes, as it turns out: sideways. New volunteers, asked to list the fibre crafts that they know, include other creative skills that they would like to share. The successful model that Loose Ends has pioneered seems ripe for helping more crafts. If two suburban knitters can quit their day jobs and nurture a global community, perhaps finishers can be found to complete works in other creative fields. Pushed to reveal whether they might expand beyond fibre crafts, the founders hesitate. Then both start talking at once. “Woodworking,” says Simonic. “We’re exploring that. I’m actually meeting a woodworker next week to talk about what it might look like. But we’re just tinkering.”

“People are demanding it already,” says Kaplan, laughing. “Plenty of men tell us that they’re keen for us to begin offering woodworking. One guy says that it will finally let him buy that expensive tool that he could never justify before.”

“But we’re not ready yet,” says Simonic. “We need to fund our technology first, so we can get all of this stuff into an app. But in two, three years? Check back.”

As it passes its second anniversary, Loose Ends has been expanding into new countries – Armenia being the latest – and maybe new crafts. Looking back, which achievement stands out for the founders? The two old friends look at each other. Kaplan speaks first.

“We have a local woman in her eighties, an amazing knitter and one of our earliest finishers,” she says. “At the beginning she completed one of our first pilot projects. Afterwards she came up to me and said, ‘I’ve been afraid to start a new project for my own grandkids because I didn’t know what would happen to me; I didn’t know if I’d be here to get it done. But what you’re doing has given me the courage to keep crafting.’ And she sent us pictures after she made her first new piece for the children.”

Simonic nods. “The work we do lets older people, or people who may fall ill, continue to do something that means so much and that makes them happy,” she says. “With Loose Ends around, they no longer have to worry that the gift that they’re making will be thrown away or end up in some charity shop.”

Connecting generations, cementing legacies and giving elder craftspeople the assurance to carry on – maybe these 28,000 volunteers shouldn’t be called finishers. Their achievements seem to warrant a new name: continuers.

And perhaps the worldwide success of Loose Ends is a sign of something else as well. It shows that, even in today’s metaverse moment, not all of the important innovations are digital. Sometimes the best way to pass down a skill – and a gift – is still from hand to hand.

Sticking around: How the Post-it changed the way we work

The origin of sticky notes is the stuff of r&d legend. Spencer Silver was a research chemist at 3M, the Minnesota-based industrial and consumer products company, seeking to concoct an adhesive strong enough to hold airplane parts together. Instead, in 1968 he developed acrylate copolymer microspheres, a sticky adhesive that came off surfaces easily and didn’t leave residue. Silver evangelised his invention within 3M and patented it in 1972 but no obvious commercial application emerged. Another chemist learned about Silver’s adhesive and thought it would make for a handy bookmark. The eureka moment had come, and 3M launched the Post-it Note in 1980.

In the 40-plus intervening years, 3M has sold billions of sticky notes and manufactures enough of the paper each year to reach the moon and back 13 times. The product has twice the brand trust as its nearest competitor, according to surveys. While the original 76mm by 76mm squares in canary yellow continue to be the top seller, Post-it Notes now come in more than 500 variations in 26 colours.

Sticky notes have ardent fans across all disciplines and ages. But Adrienne Hovland, who was until recently global portfolio director for Post-it Note, finds designers the most dedicated. “I feel like a celebrity when I walk into a creative agency or design studio,” she tells monocle. Digital competitors haven’t put a significant dent in the sticky note’s appeal and Hovland attributes the paper Post-it Note’s longevity to simple human cognition. “There’s something about being able to see it all in front of you that clarifies what you need to do, how you want to group things and where you need to go next,” she says. “That’s inherently why they endure with the design community.”

Monocle spoke to four US creatives with a professed love of sticky notes about how the humble product helps them bring thoughts to life, convey ideas to clients and keep them organised.

1.

Jenny and Anda French

The architects, Boston

How do you get about 50 households to agree on a design for their future home? With sticky notes, of course. Jenny and Anda French, who together run Boston-based architectural practice French 2D, took on the ambitious task of designing a co-housing building in Massachusetts. The clients consisted of a range of potential residents, from baby boomers to millennials, who all agreed that they wanted to live together in individually owned flats with private kitchens and living rooms that are attached to a common house with a larger kitchen, dining room, music space and garden.

Translating this into concrete and wood, however, meant securing consensus on every detail. So the team devised a traffic signal-esque colour-coded sticky-note scheme of green, yellow and pink Post-its that were distributed to the 30 households. Everyone also received a single blue sticky note to signal exceptional approval of a design option.

“This is your voice and this is how we can see all of your voices together,” says Jenny (pictured, on right, with Anda) of how they described the scheme to their clients. The process helped the group to choose the building’s design, from its shape, unit types and common spaces to the materials used and connections to outdoors. The green and yellow notes illustrated sufficient consensus to move on without wasting time, while the hot pink notes created an instant “red light” moment for the group to hash out their differences in real time.

It took 12 workshops and seven years to bring the 30-unit project to fruition. But when the residents moved into their new homes in 2023, they had the satisfaction of knowing that both they and their neighbours fundamentally agreed on every detail – any leftover hot-pink sticky notes could be drafted for grocery lists instead.

2.

Mario García

The media strategist, New York

Cuban-American journalist Mario García is a highly sought-after design and editorial consultant who works for various media outlets around the world. He advises the likes of The Times in the UK, Singapore’s The Straits Times, Der Tagesspiegel in Germany, and Khaleej Times of Dubai, on how to improve their mobile storytelling offerings.

Whichever newsroom he lands in, however, must provide one simple tool that is absolutely essential for him to run his workshops: sticky notes. That’s because he trains his clients on how to deploy visual assets in a mobile story – where to intersperse videos, photos and graphics with text – by mapping them out with sticky notes, preferably the yellow ones. He picked up the technique from a New York Times staffer who became one of his graduate students at the Columbia University School of Journalism.

“Sticky notes are a functional way for a journalist who normally works with words to understand how visuals can become like paragraphs that advance the story,” he says.

To illustrate his point, García explains that the average time readers spend on a mobile story clocks in at 30 to 33 seconds. So an outline with 15 sticky notes – representing 15 different assets – makes it clear that some of the visuals need to go, or readers are unlikely to scroll through the story until the end. “Sticky notes help you see where you are with visuals.”

3.

Marta Bernstein

The graphic designer, Seattle

A potpourri of typefaces articulating various building names, directions, department titles, exhibition descriptions and other bits of information adorn signs of different shapes and sizes inside Studio Matthews, a Seattle-based design practice. Italian graphic designer Marta Bernstein has had her hand in many of these projects as the firm’s co-creative director.

When Monocle visits, Bernstein is fresh off a meeting with a neighbourhood business improvement district and is peering over a clutch of sticky notes in orange, yellow, pink and light blue affixed to a map. Each refers to a local landmark with text jotted down explaining the location’s significance. This early-stage information-gathering workshop was designed to inform the direction of travel for an as-yet-undefined project – the end result might be wayfinding signage, informational maps or a local history kiosk.

For Bernstein, having the client huddle over a physical map rather than collecting ideas to type up on digital charts is vastly preferable. “People are looking at things instead of doing things,” she says. “The fact that people are standing, writing and physically moving in the space makes them way more engaged than just sitting and looking at a screen where someone is adding input.”

Bernstein says that four colours are the maximum she’ll bring to an engagement; more than that and any colour-coding scheme begins to fall apart. monocle peers inside the studio’s supply drawer where sticky notes – all Post-it brand, in a mix of 76mm by 76mm square and memo-sized – are neatly arranged. The latter are particularly useful for intraoffice communication. “It’s nicer to leave a sticky note on someone’s desk than to send them a Slack message,” she says.

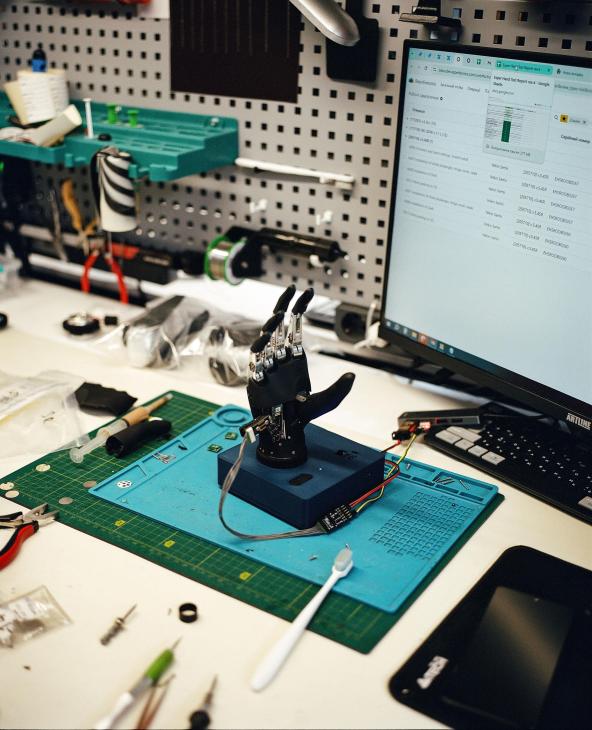

How AI is lending a helping hand to bionic limbs

A couple of years ago, Tommaso Lenzi, an assistant professor at the University of Utah, picked up his phone and sent a photo to Hans Georg Näder, the owner of Duderstadt-based Ottobock, one of the world’s largest prosthetics manufacturers. The image showed a sleek, red-and-black metallic leg. Lenzi had spent almost a decade developing the robotic limb; after countless prototypes and trials, his lab in Salt Lake City was finally happy with the design. “A long time before then, Näder had left me his card,” says Lenzi. “I finally texted him and said, ‘I think I’ve got something.’

Using sensors and custom-built, AI-powered controls to anticipate the movements of the body, the Utah Bionic Leg enables above-the-knee amputees to climb stairs, hike and cycle. Though scientists across the globe had devoted countless hours to developing robotic legs, most previous attempts had been too clunky and complicated to be of much practical use. The Utah Bionic Leg is both lighter and stronger than the average human leg. “We were able to achieve a weight and power that had been thought to be impossible,” says Lenzi.

Soon after receiving Lenzi’s message, Ottobock made a big donation to the academic’s lab and signed a contract to start developing the Utah Bionic Leg for mass production. The company had cause to move fast: a transformation is under way in the prosthetics industry, with technology previously considered the stuff of science fiction becoming a reality. Thanks to advances in robotics, machine learning and materials, as well as generous investments from the US military and the European Union, scientists can now build prosthetic limbs that can match, or even outperform, biological ones. These are often called “bionic” – a buzzword that simply means engineering inspired by biology.

There are several mechatronic hands on the market that read muscle activity in the residual limb and, with the help of AI, can translate it into complex hand movements. Paralympians on running blades can now sprint as fast as Olympic athletes on their own legs. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a new lab filled with neurologists and engineers is developing neural implants that allow the user to control a robotic prosthesis directly with their mind.

The field’s inventions can sound like a teenager’s cyborg fantasy (and often that’s how they begin) but there is a real and urgent demand for them. The World Health Organization estimates that as many as 40 million people across the globe require a prosthesis – and the number is growing. Most users today are medical amputees (often as a result of diabetes) and people born with a limb difference. Still, it can seem that the sector hasn’t come far enough since the early days of industrial production, when veterans of the First World War painfully hobbled around on wooden legs. Even in high-income countries, arm amputees are often told to make do with a hook. There is still no widely available prosthesis that makes it possible for above-knee amputees to climb stairs.

“This industry can be very slow-moving when it comes to innovation,” says Costa Rican scientist Jose Gonzalez. “Understandably, people have concerns over safety.” Monocle meets Gonzalez at Ottobock’s headquarters in Lower Saxony, where he works as head of research, Germany. With more than 9,500 employees worldwide and a valuation of about $5.8bn (€5.5bn), Ottobock is one of the industry’s giants. Much of its production line is still dedicated to versions of the C-Leg, a hydraulic device that was introduced in the 1990s. “The machine should ideally adapt to the person,” says Gonzalez. “Right now, the person still has to adapt to the machine.”

Gonzalez’s job is to bridge the vast gap between cutting-edge technologies being developed at universities and the devices being put into mass production. He is working with Lenzi to develop the Utah Bionic Leg, alongside dozens of other projects. The aim is to develop something that can be mass-produced to last for years, comes with a genuine benefit to the user and isn’t prohibitively expensive. “Much of what we do will never see the light of day,” he says. “You have to ensure that it’s a win-win for all parties involved.”

Even with a successful product, a complex network of people must work together to bring it to patients. Doctors have to recommend it, insurance companies need to be convinced of its necessity and prospective users must be assured of its safety.

Among the upstart outfits that are aiming to eat into the market share of firms such as Ottobock is Ukrainian start-up Esper. The company was founded in 2019 by Dima Gazda, a medical doctor and hobbyist electrical engineer who was interning at a hospital when he was struck by how unappealing the options available to amputees were. So he set about developing the Esper Hand, a bionic device that can be controlled by the user through sensors and makes use of machine learning. The company that he set up now has 70 employees, with assembly facilities in Kyiv and its headquarters in New York.

Gazda spent years perfecting the design with two mechanical engineers. “The process was meticulous, iterative and not very pleasant,” he says. In contrast to many Hulk-like alternatives, the Esper Hand is almost dainty, with a female and male size. Its considerate details include fingertips that can be used on a touch screen. The hand has also already passed a tough practical test: it has been fitted to dozens of Ukrainian soldiers.

At Esper’s office in Brooklyn, Monocle meets Emily Peterson, who is sitting opposite Gazda. Born with a limb difference, Peterson is an avowed fan of the Esper Hand. Like most prosthesis users, she has a custom-made socket (the part that fits to the residual limb) and switches between several artificial hands. She tells Monocle that, with the availability of newer prostheses such as the Esper Hand, simply getting through the day with a synthetic limb is no longer the biggest challenge. “The problem now isn’t how to interact physically with the world,” she says. “It is to have the world be comfortable with you.”

Lenzi says that this is where design comes into play. Most common prostheses can be fitted with skin-coloured gloves that are intended to make the device almost indistinguishable from the rest of the body. While the Utah Bionic Leg takes inspiration from the shape of the human calf, ankle and foot, no attempt is made to hide the fact that it is a machine. Lenzi’s team made the deliberate choice to make the leg brightly coloured and futuristic. “Part of the reason why people hide a prosthetic is that they feel that it signals disability – that they are weak,” he says. “But as these technologies come out, there will be a huge shift.”

To illustrate this idea, Lenzi points to a prosthetic that’s so widespread that people rarely think of it as one. “I wear glasses but you wouldn’t say that I’m disabled,” he says. “That’s because lenses work really well and there’s no difference in my ability to participate in society. If you look at the design of glasses, people aren’t trying to hide them. They’re part of their expression.” When it comes to the next generation of prosthetics, the real sign of success will be when wearing one isn’t considered remarkable at all.

Back on their feet

While hi-tech prosthetics are trickling into the market, the World Health Organization estimates that, as a result of the lack of access to high-quality healthcare across the globe, only one in 10 people who need a prosthesis have access to even basic assistive products. Swiss-Kenyan venture Circleg is working to address this with a low-cost prosthetic leg that was launched last year. “Most people who need prosthetics either don’t have access to it or can’t afford it,” says co-founder Simon Oschwald. “There is a huge gap between provision and demand that we are working to fill.”

Oschwald and Circleg co-founder Fabian Engel originally developed the prototype for the prosthesis as their bachelor’s thesis in industrial design. The leg is modular, size-customisable and can be assembled locally in Nairobi. It is sold as part of a holistic package that includes orthopaedic training for fitting sockets and starts at as little as $350 (€332) – a fraction of the prices for state-of-the-art prostheses such as Ottobock’s Genium X4, which can run into six figures. After a year in business, Circleg has B2B clients in East and West Africa, and has just expanded to Latin America. “When you lose a leg, the main barrier is that you are seen as disabled and unable to provide for the community,” says Oschwald. “We are trying to shift that perspective.”

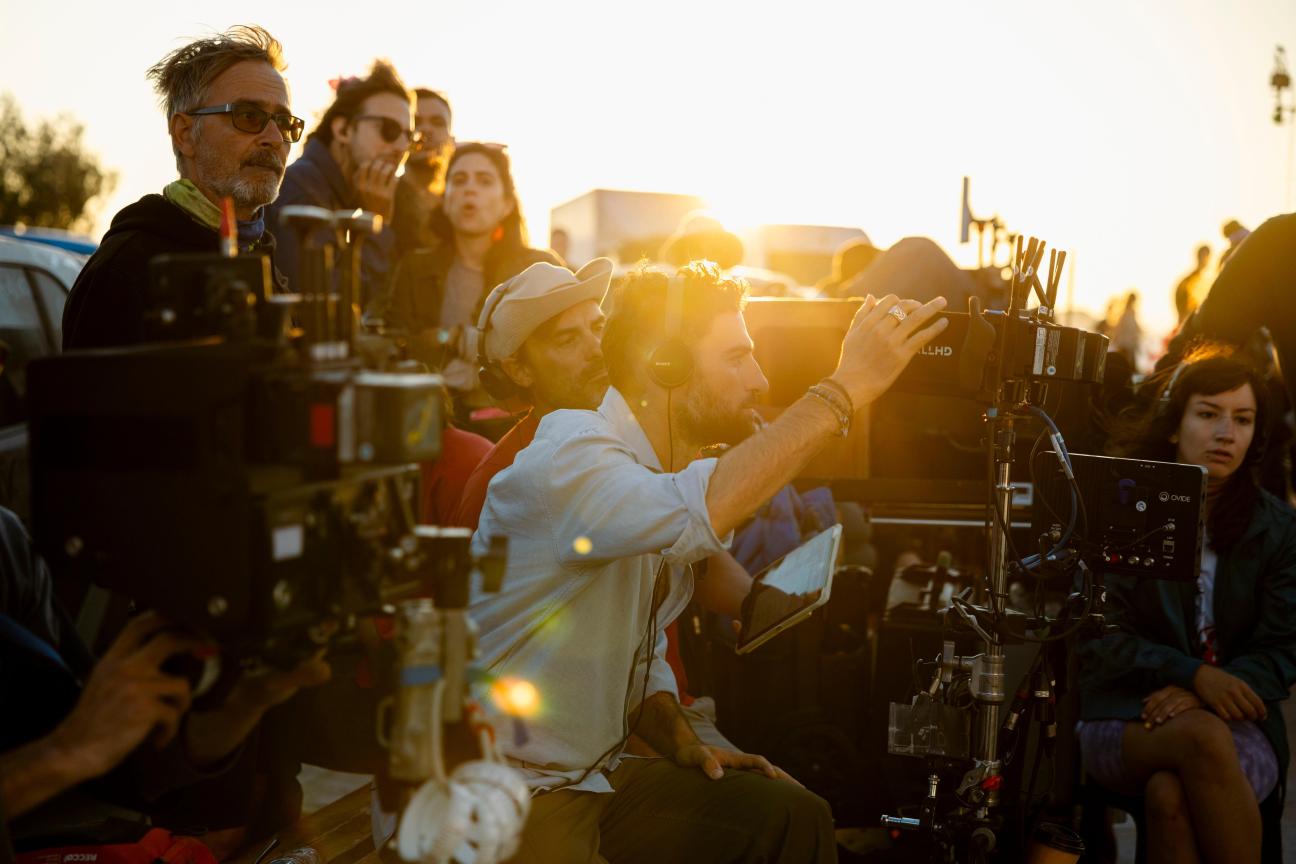

Behind the scenes at Studio Galazio: Challenging Greek stereotypes through regional storytelling

It’s a clear day in Mykonos and Studio Galazio is shooting its debut feature along the Greek island’s port promenade. No one, however, has banked on the six cruise ships that have decided to show up, delivering hundreds of day-trippers onto terra firma. Crew members in hi-vis yellow gilets are trying to move through the crowd, redirecting those who have paused to take pictures. The film’s director of photography crops the shot tighter to keep the disobedient tourists – including a Spaniard who is convinced that she has spotted Paris Hilton (she hasn’t) – out of frame. “We honestly haven’t had too many difficulties,” says the film’s writer, director and co-producer, Christopher André Marks. “Shooting live at the port was always going to be a challenge because it’s so busy.”

Sporting a half-unbuttoned shirt, Marks is rarely stationary, giving advice to his actors one minute and then shifting to watching the action on a handheld screen the next. Alongside his numerous jobs on set, he’s also the founder of Studio Galazio, whose name is taken from the Greek for “light blue”. This film, which everyone on the shoot is tight-lipped about, is an as-yet-untitled feature loosely billed as a heist comedy in the vein of Ocean’s Eleven. It could see a release in late 2025.

Marks is a Greek-American raised in California who spent years working in film production in New York, including for the likes of ESPN and HBO. The 36-year-old’s breakthrough moment was directing King Otto, a 2021 documentary about Greece’s improbable triumph in the Euro 2004 football tournament under German manager Otto Rehhagel. The film was released in 75 countries and boosted the profile of Studio Galazio, whose mission to get more Greek stories on screen. “Being Greek is kind of a dominant trait; it’s an inherent part of who you are,” says Marks from a table at a nearby restaurant, as actors and crew break for lunch. “But I also see Greece as an opportunity.”

Marks is quick to recognise that Greece is already having what some might call “a moment”. The country has been steadily recovering from its 2009 economic crisis, with Athens luring investors and remote workers as a result of its relatively low cost of living and clement weather. Marks hopes to “add to the momentum” of Greek cinema, which has seen Hollywood arrive on its shores thanks to an attractive 40 per cent tax-rebate programme. There is also plenty of regional talent, from production crews to actors. Take Poor Things director Yorgos Lanthimos, who rose to prominence in 2009 following the success of his Greek-language film Dogtooth, which won the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes Film Festival. The recent popular Greek Netflix drama series Maestro in Blue is further proof that the talent pool is deep. Two of the show’s leading figures, Klelia Andriolatou and Maria Kavoyianni, also happen to be in Studio Galazio’s new production. When Monocle visits, Andriolatou is shooting a scene at windmills near Mykonos’s port with celebrated actor Panos Koronis.

As part of its mission to showcase Greek stories, Studio Galazio combines universal themes with Greek topics, which are neatly packaged for a global audience that’s increasingly comfortable with foreign content. Marks is keen to show that Greece is more than just a sunny setting for films. “The country makes for a beautiful backdrop; many foreign producers shoot here,” he says, referencing features such as Richard Linklater’s 2013 romantic drama, Before Midnight. “But what we’re trying to do is showcase Greece from a storytelling perspective.”

Given that the characters in Marks’s Mykonos film are from different parts of the world, English is the predominant language as the drama unfolds. But if two Greek characters are speaking, then the scene plays out in their native tongue. Most of the crew are Greek, as are some of the producers, including basketball player Giannis Antetokounmpo, who has a production role via his company Improbable Media. But there are also Italian, French, Spanish and Turkish speakers on set. They are joined by international on-screen talent including the likes of US actor Vito Schnabel and Italy’s Riccardo Scamarcio. “The ensemble aspect of the film was key for me,” says Marks. “Ocean’s Eleven was shot with Brad Pitt, Matt Damon and Bernie Mac. I really wanted to have that same kind of team, where every single actor could carry a film on their own.” Still, Marks admits that the budget for the shoot is modest, though co-producer Ginevra Tamberi is quick to add that it is on a par with some other European films.

We shift locations to the interior of one of the windmills that faces the twinkling Aegean. On the day Monocle visits, it doubles as a make-up studio. Tamberi is sitting on a sofa and keen to emphasise the tightknit nature of the crew. “They have all grown so close to Chris,” she says. “They see the project as a love letter to Greece – and they want to be a part of it.” Tamberi has known Marks for more than a decade and the pair have always said that they would make a film together. Tamberi left a job at Amazon MGM Studios before making it happen and is sure that it was the right decision. “I believe in Chris,” she says. “And I believe in storytellers. They should be given every opportunity to showcase their vision.”

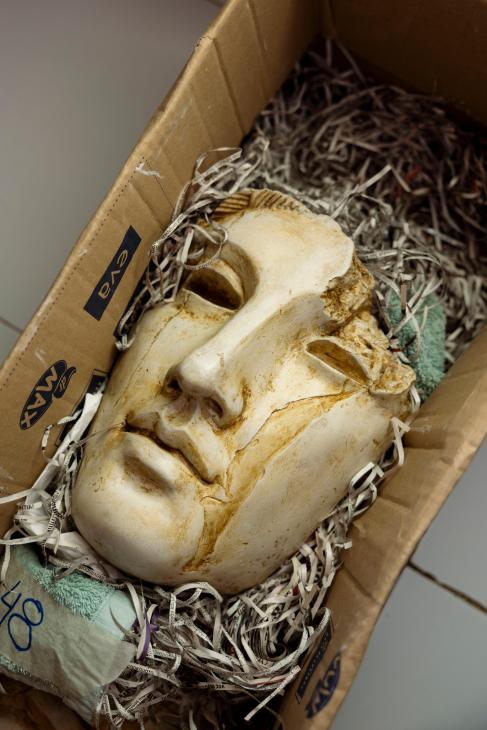

But Tamberi isn’t the only one to have been left with a lasting impression of Marks. The film’s production designer, Kostas Pappas, is in charge of scoping out and dressing sets, including a fishing village that we visit about a 30-minute drive from the windmills. Pappas is a colourful character who cut his teeth in New York and has worked on films such as The Bourne Identity and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider – The Cradle of Life, both of which were shot in Greece. Standing beside one of the windmills as the sun goes down, he describes being struck by Marks’s humble demeanour when he first called him about the project. “For me, it was a comfortable job,” he says.“What was more interesting was the way that Chris approached me. I liked his story as a Greek trying to find his roots.”

While there is a lot resting on Marks pulling off the Mykonos heist film, it hasn’t stopped him from planning future productions. He is currently laying the groundwork for two other projects: a biopic and what he calls a “prestige series”, an industry phrase used to refer to complex, big-budget content. It’s all part of an effort to build a recognisable brand for Greek film. “People know when they’re watching French or Italian cinema,” he says. “It would be great if Greece had that same kind of identity.” Perhaps his Mykonos feature will be the first step towards making it happen.

Lights, camera, Athens:

Projects filmed in Greece

1.

Mykonos (Title TBC), 2024

Studio Galazio’s debut follows a group of thieves as they rob rude tourists – and a love story that crosses the divide.

2.

‘Maestro in Blue’, 2022-present

Netflix’s first Greek series, on the island of Paxos, taps into forbidden love.

3.

‘Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery’, 2022

A murder mystery set on a billionaire’s private island.

4.

‘Beckett’, 2021

A tourist loses his girlfriend in a car accident and is caught up in a political manhunt.

5.

‘Tehran’, 2020-present

This Israeli Apple TV+ series turns parts of Athens into Iran’s capital.

How smaller brands are outpacing their sportswear competitors

You would be forgiven for assuming that 2024 was a rough year for the sportswear industry. News headlines repeatedly turned to the downgrade in Adidas’s China business, as well as executive reshuffles at Nike and the drop in the sportswear giant’s revenues, marking its worst downturn in a decade. Yet the poor performance of the sector’s major players doesn’t represent the industry at large. For some, it’s quite the opposite, says Erwan Rambourg, global head of consumer and retail research at HSBC. “The leader has been experiencing so much pain and there’s a tendency to project Nike’s performance as a proxy for the sector,” says Rambourg, who sees the past year as relatively healthy when it comes to course-correcting inventory levels and promotional spending.

Sportswear’s current dynamic is best described as a dichotomy between the incumbents and the challengers. On one side, household names Nike and Adidas find themselves at very different stages of recovery; on the other, newer and smaller upstarts are snapping up market share across categories including technical footwear and performance wear. The leaders in the latter camp – such as On, Hoka and Salomon – are doing just fine. This is evident when you walk down a prime shopping street, from New York’s Madison Avenue to London’s Regent Street – large spaces previously occupied by contemporary fashion labels have now been taken over by the likes of On, Californian performance-wear labels Vuori and Alo or Canadian outdoors specialist Arc’teryx. Inside boutique gyms, the usual abundance of Nike swooshes and Adidas’s signature striped leggings have been replaced by sleeker, logo-free gear and Salomon’s XT-6 lace-up trainers. With consultancy firm McKinsey & Company predicting that the global sportswear industry will grow by 7 per cent a year by 2027, there will be more growth opportunities up for grabs. “It has been an incredible year of growth,” says Joe Kudla, founder and CEO of Vuori, which is known for its comfortable sweatpants and matching workout sets. The brand, which started 10 years ago from Kudla’s garage, has recently raised $825m (€779m) and has been valued at $5.5bn (€5.2bn). As a comparison, Nike is valued at more than $114bn (€107bn) – more than double that of the next-biggest player, Adidas.

Kudla recently travelled to London to celebrate the opening of Vuori’s new shop on Regent Street. This is the brand’s first flagship outside the US but won’t be the last, given its current pace of growth. The plan is to have 100 shops stateside by 2026 and 50 in other countries in five years. Vuori began as a men’s concept when Kudla, who at the time was getting into yoga, had trouble finding high-quality workout clothes that he didn’t want to change out of immediately after exercising. “The market was dominated by the big sports brands and they defined the look and feel of our category,” he says. “It was shiny synthetic materials, big brand logos, bright colours. It was more aligned with playing sports than it was living life outside sport.” The brand went on to add womenswear to its offer in 2018 and the category has grown to represent half of its sales.

Kudla maintains that, though Vuori has eaten into market share previously held by the likes of Nike and Lululemon, it doesn’t need bigger players to fail for his brand to grow. Indeed, the global athleisure market is projected to have a 9.3 per cent compounded growth rate to reach $663bn (€626bn) by 2030, according to Grand View Research.

But it’s a competitive market segment and the expansion of upstarts such as Vuori or Alo is often considered to be one of several downside risks for legacy players. At Nike in particular – which last December slashed its outlook for the fiscal year and predicted that sales would only grow by 1 per cent – stale launches, overexposed heritage designs and an overzealous wholesale strategy, followed by an abrupt retreat, made way for innovative younger brands to shine. Nike veteran and CEO Elliot Hill, whose return in October 2024 was celebrated by employees, has a mammoth task on his hands: a turnaround that necessitates rebuilding the brand’s wholesale network; launching fresh, innovative new shoes to excite shoppers; and reinvigorating the sleepy Nike brand as a whole.

Sporting goods expert Matt Powell, who serves as an adviser at BCE Consulting and Spurwink River, says that Hill is the man for the job. “Nike’s problems are fixable and Hill is the right person to fix Nike,” he says. “But none of these problems are quick fixes. While we might see green shoots in 2025, I don’t expect we’ll see the brand really turning around.” Bernstein analysts say that Nike’s product pipeline won’t show signs of revival until the first half of 2026 at the earliest. As for Adidas, it’s a little further down its recovery journey but it will still need to exercise caution next year, especially when it comes to hit styles such as the Samba, which have become oversaturated.

On the other side of the fence, what Nike has done wrong mirrors what the upstarts have done right: designing innovative products in neglected niches and nurturing wholesale relationships alongside their own shops. Then there are strategic tie-ups. Asics’ long-term deals with fashion-forward labels such as Cecilie Bahnsen and Kiko Kostadinov are a prime example. Unlike the flash-in-the-pan collaborations of years past, these crossovers feel in line with the brands’ identities and are generating more demand. When done right, they also reward both parties: niche fashion brands get access to new categories and technical supply chains, while sportswear players benefit from fresh creative direction.

For Salomon, which is owned by Amer Sports, the fashion angle is top of mind too. The brand, which has inked crossovers with Comme des Garçons and MM6 Maison Margiela, is doubling down on its fastest-growing Sportstyle category by opening its first shop, in Paris’s hip Le Marais, stocking limited-edition collaborations and signature styles such as the XT-6.

Powell also uses the example of New Balance, which is using collaborations to reintroduce archive designs while keeping commercial styles readily available to meet trickle-down demand – see its collaboration with Aimé Leon Dore, which raised the profile of its classic 550 trainers. Beside the New York-based fashion brand, New Balance has also been working with the likes of Miu Miu on a series of sell-out redesigns of its 530 and 574 sneakers, as well as Japan’s Junya Watanabe, with which it teased a trainer-loafer hybrid at Paris Fashion Week in January 2024.

Looking ahead, the sportswear sector will continue to evolve. A flurry of sporting events in 2024, from the Olympics to the Euros, reminded us that in an on-demand world, sport is one of the few things that will still grasp our focus live and en masse. Luxury brands are tapping in, creating opportunities and competition for existing sportswear players: see LVMH’s €150m Olympics deal and the French conglomerate’s decade-long Formula 1 partnership. This momentum will continue, particularly as interest in women’s sports gains ground.

Nike and Adidas aren’t going anywhere. According to RBC Capital Markets, the rivals still hold a quarter of the global sportswear market. But walls in sports shops and department stores are already looking different than they did five years ago, mirroring the market’s splintering. Despite both Adidas and Nike’s incoming rebounds, Powell doesn’t see a return to those brands’ previous domination. For new establishment trainer makers, such as On and Hoka, longer-term growth is on the horizon if they manage the marketplace well and create covetable clothing – a category that neither has truly cracked. “The big trees in the forest have lost foliage so the sun is finally reaching the ground and green shoots are popping up,” says Powell. “It’s great for the industry. The more competition we have, the better it’s going to make everybody.”

Nikolaj Hansson

Founder, Palmes

Copenhagen-based label Palmes is one of the upstarts honing in on sportswear niches and snapping up market share. Since it was launched in 2021, the brand has made a name for itself with its tennis-inspired clothing.

The brand’s founder, Nikolaj Hansson, was recently named creative director of Italian heritage sportswear brand Diadora’s Legacy line but his focus remains on tennis.

Why did you choose the focus to be on tennis with Palmes?

I don’t think that the big companies really cared about tennis. There seemed to be no need to innovate because they were catering to a very conservative audience. But now a lot of my friends in New York who used to skate are into tennis. It has opened up culturally and the idea with Palmes is to break down that barrier. We’re growing healthily, and we were profitable as of last year, which was only our second full fiscal year.

What have the bigger players been missing?

Emotion – that’s what we’re all buying into. It’s tough when you’re bigger to have the same sense of identity but it’s about communicating stories and feelings with depth, while also not taking anything too seriously.

What are the biggest challenges for sportswear brands today?

There are markdowns, which are hell. Some of our autumn/winter collection is already marked down during the mid-season sales but we’re only a few months into the season. It’s also about being aware of the world: we have so many issues with US imports because of the trade barriers. Everyone’s swimming against the current.

What do you make of the increased interest in tennis?

We’ve been really lucky with timing but we’ll keep doing exactly what we’re doing if the trend passes. I’m kind of excited for it to be over because there will be less noise. People will always move on to the next trend but tennis will always be relevant. Down the line, we would like to do another label for performance tennis wear.

Where’s your favourite place to play?

The Courts. It’s a hotel near Palm Springs with courts that have views of the San Ysidro mountains.

Joint ventures

Asics’ revival

Asics has raised its profile and increased demand for its classic styles, such as the Neocurve, thanks to collaborations with fashion-forward labels, from London’s Kiko Kostadinov to Copenhagen’s Cecilie Bahnsen, which added floral appliqués to the classic Gel Terrain trainers. The fashion labels get to experiment with materials, while Asics refreshes its creative direction.

530 SL by New Balance X Miu Miu

Raising the heart-rate

Salomon wonders

It has become impossible to enter a gym without spotting Salomon’s sleek XT-6 trainers. The brand is becoming a go-to for both fitness enthusiasts and fashion-forward clients, and the firm is doubling down on its Sportstyle category, with new dedicated shops in Paris’s Le Marais and London’s Soho. Look out for limited-edition styles by MM6 Maison Margiela and Comme des Garçons.

The grape and the good: Chandra Kurt’s 20 best bottles for 2025

1.

Red: Cepparello, Isole e Olena, Toscana

Old World favourite

A Tuscan icon. Pure sangiovese from the best terroir. Cepparello is the name of a troubled character from the 14th-century Decameron by Boccaccio. The wine itself is rather friendlier.

2.

Red: Hirsch Vineyards Pinot Noir, California

New World beauty