“This exercise is about making the unreal feel real” says Major Hamish Waring as he stares intently at a map dotted with dozens of red, blue and yellow pins. The softly spoken British Army officer is speaking to Monocle in a bunker hidden deep within a forest near Estonia’s border with Russia. Waring’s battalion, the 2nd Scots Battle Group, is taking part in Exercise Hedgehog, the largest-ever military exercise to take place on Estonian soil, featuring more than 16,000 troops from Nato countries including the UK, France, Canada, the US and Sweden. “We’re here to simulate defending Estonia from an aggressor,” Waring adds. The current “aggressors” to which he is referring are Swedish units trying to infiltrate the base. Nato’s newest member applied to join the alliance in May 2022, three months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and was finally admitted in March 2024. Since then, Swedish soldiers have been attached to Nato’s Forward Land Forces (FLFs), units deployed in advanced positions near the alliance’s 2,500km (1,600 miles) border with Russia.

It is the FLFs that make up Hedgehog’s personnel and the key aim of the three-day exercise is to improve interoperability. The size and military budgets of Nato’s 32 member states dwarf those of its most likely adversary – but Russia’s forces have the edge in combat experience and the advantage of a common language and military culture. Part of Nato’s challenge in meeting the threat from Moscow is to better integrate its members’ myriad languages, combat systems and procedures. “The biggest challenges are practical,” says Waring. “It might seem small but a misinterpreted message on a battlefield can have serious consequences.” Language adds a layer of complexity that could cause a breakdown in key moments. “The British aren’t the best at languages,” Waring chuckles. “And while many allies speak excellent English, there are nuances – especially in tactical terms – that need clarity.” Lieutenant Colonel Henrik Rosdahl, commander of the Swedish South Skåne Regiment P7, echoes Waring. “We’ve all trained extensively but integrating forces with different languages and cultures is like learning to dance together when you each know different steps.”

Estonia’s position near a heavily populated part of Russia makes it particularly vulnerable to attack. “For Estonia, the threat is real and immediate. These exercises are not theoretical drills but essential preparation,” explains Kristi Raik, a Baltic security expert and director of the International Centre for Defence and Security, a Tallinn-based think-tank. “They signal that Nato is united and ready to defend its members.” The Baltic country has taken serious measures to enhance its defence capabilities since 2022. “Estonia has pledged to up its defence spending to 5 per cent of GDP, which is among the highest [per capita] in Nato,” says Raik. “They’ve also developed rapid-evacuation procedures and integrated their civilian population into defence plans.” Alongside simulated military operations, Exercise Hedgehog also includes an evacuation drill as well as a first-ever test of the nation’s public-alarm system, which simulates how civilians and military personnel would respond to sudden alerts. Everyone with a mobile phone in the country, including Monocle, received a message from the Estonian Defence Forces at 15.00 on 14 May that read, “Public warning system test – no real danger!” The authorities were careful not to incite panic, and the exercise was about testing whether the nation-wide alarm system would work in times of real peril. “It’s about readiness – making sure that everyone knows what to do if the worst happens,” Raik adds. All did not go smoothly, however. There were considerable delays across Estonia in sounding the sirens. The Estonian Defence Forces later admitted that only two-thirds of the alarms triggered on time.

Most Estonians were likely unfazed by the warnings. As in other Baltic countries and Finland, there is a strong sense of crisis preparedness here. More than 80 per cent of the population is in favour of taking up arms to defend the country against an attack, and there’s widespread support for increased military spending and large-scale exercises such as Hedgehog. The combat in Ukraine has demonstrated that modern warfare can be both attritional and technologically advanced. “The conflict has taught us invaluable lessons,” Waring says. “It has shown the importance of rapid deployment, interoperability and sustaining supply chains under pressure.” To that end, the UK maintains a brigade – roughly 5,000 soldiers – on 30 days’ notice to deploy to the Baltic. “We’re ready to move here on short notice to support Estonia and other allies,” he says. The speed of this deployment was also put to the test during Hedgehog. In under 48 hours, a 1,700-strong battle group deployed from the UK to Estonia via rail, sea, road and air. “A credible deterrent requires more than presence – it needs the capability to reinforce quickly and effectively,” Captain Marcus Worthington from the British Army tells Monocle as his platoon of Royal Engineers practises dismantling a roadside improvised explosive device (IED).

The kind of rapid deployment that Worthington is referring to is at the heart of Nato’s plans for the defence of its eastern flank. At the alliance’s 2022 Madrid Summit, it announced a shift in its strategy from the so-called “tripwire” approach to a more robust posture. In practice, this means pledging to radically increase Nato troops’ presence near its borders, meaning that it can deploy soldiers quickly in order to defend every inch of ground from the first hour of an attack, instead of letting territory fall into enemy hands and then liberating it later. It’s a tough ask, as Raik points out, given the hundreds of thousands of troops that Russia would be able to deploy to the Baltics (were they not holed up in Ukraine). “But it’s a step in the right direction”, she admits. “As the war in Ukraine has shown, taking back conceded territory from Russians is challenging”.

Estonia’s defence strategy relies heavily on reservists, civilians who have completed mandatory military training. In 1991, Estonia introduced compulsory military service for men, today the country has 230,000 trained reservists, nearly one-fifth of the population. Integrating them into Nato is one of Hedgehog’s main objectives. “I did my military service three years ago and was called upon to refresh my training at Hedgehog,” 21-year-old IT student Peeter Lääniste tells Monocle in a makeshift lookout post. He’ll miss two weeks of university, meaning that he will have to make up for lost time by taking several exams – but did not hesitate when called upon. “Living next door to Russia, you have no excuses to stay at home during exercises like these,” he says. While we’re speaking, a squadron of Nato fighter jets booms overhead. Lieutenant Colonel Madis Koosa, who grew up next to an airbase during the Soviet occupation of Estonia, gets visibly emotional. “As a child I used to hate the sound of the Soviet planes but this sound that we just heard, to me that is the sound of freedom.”

At its core, Hedgehog is as much a political exercise as a military one. “We want to show that Nato stands united,” Koosa says. “With forces from across the alliance, including new member states, we want Russia to know that we stand together. An attack against Estonia is an attack against the mightiest military alliance ever to exist.” Despite the unified front, Nato faces significant challenges. Disagreements at the highest level, especially between western Europe and the US, make the alliance appear in disarray. With US military support no longer a cast-iron guarantee, there is a sense that European countries need to shoulder more responsibility by upping defence spending. Then there’s the material factor. On paper, Nato is far superior to its adversary but the fact is that it has never fought a war as a single force. Meanwhile, Russia brings combat experience and troops battle-hardened from combat in Ukraine. “The question is whether Nato’s political will and military readiness will hold up in a crisis,” Raik says. “The exercises are vital but only part of the picture.”

Is Nato ready for war against Russia? As Raik points out, the consensus among security analysts (at least in this part of Europe), is that a lot depends on how the war in Ukraine plays out. “Putin has made clear that he sees the Baltics as being within the Russian sphere of influence”, she says. “If he has his way in Ukraine, he won’t stop there”. According to Raik, Baltic countries such as Estonia might be next in line. “If Russia sees Nato as weak and not able to defend its Baltic members, it might be tempted to attack”. That’s why exercises like Hedgehog are so crucial. Towards the end of the third day, Monocle meets Fusilier Parker, a fresh-faced 19-year-old Scotsman hiding from drones piloted by Ukrainians with recent battle experience. “This feels more real than any training that I’ve done before,” he says. “But we are ready, come what may”. That, in a sense, is the message that Exercise Hedgehog is hoping to send: that Nato, for all its infighting, is getting better at speaking with one voice.

In a sane world, it would be difficult to move on Odesa’s cobbled streets for young men on stag nights, city-breakers trying to avoid them and influencers photographing themselves in front of beautiful buildings resembling wedding cakes (writes Andrew Mueller). In our world, however, no budget airlines are touching down at Odesa International – or have done so for more than three years. I came here for the annual Black Sea Security Forum, which convened this past weekend. In keeping with the municipal tradition of swaggering flamboyance, the event was far from reserved about trying to draw attention to the city. The panels were held in Odesa’s glorious Opera House, while the closing-night drinks featured a performance by 2022 Eurovision Song Contest winners Kalush Orchestra.

These are not easy times in which to hold an international event here. Getting to Odesa, Ukraine’s third-biggest city, and the Black Sea’s most crucial port, currently requires taking a roadtrip from Chișinău, the capital of neighbouring Moldova. For Monocle, this proved a pretty stress-free three hours and change, as we cruised through the well-kept villages that punctuate Moldova’s wine country but skirting Transnistria, the odd little Russian proxy statelet carved out of Moldova in the early 1990s and a source of anxiety since the war’s onset that it could be used as a springboard for another expression of Russian revanchism.

The Moldova-Ukraine border wasn’t too much of an obstacle. It has been the previous experience of this correspondent that getting in and out of countries at war can only be measured in hours, if you’re lucky. We got through in not much longer than it took to get a passport stamped.

Once in Ukraine, and even once in Odesa, you can go a while without really noticing that anything is up. On the road there are a couple of army checkpoints. In the city, there are camouflage nets and sandbags outside police stations and where there used to be a statue of Catherine the Great – the launcher of a previous Russian invasion of Ukraine – there is now an improvised memorial to those lost fighting back the current onslaught. The grass around the plinth is planted with photos, banners and blue-and-gold flags inscribed with names and dates.

But Odesa’s shops, bars and restaurants are mostly open, the parks are full of people doing their best to enjoy the summer and life gives every impression of going on. Here, as elsewhere in Ukraine, you can download an app that apprises you of air-raid alerts. There were a couple on my first day and if these ever did cause Odesans to scramble for the shelters, they’re over it now.

Which is not to say that the risk is not real. Within the past week or so, Russia has launched some of the heaviest drone and missile barrages of the entire war. A missile strike on Odesa’s docks killed three people and a drone raid in the city’s suburbs damaged residential buildings. It might seem strange that Odesans have grown used to this. It should seem outrageous that their fellow Europeans have.

On 24 February, Ukraine will observe the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Vladimir Putin’s mooted 72-hour lightning conquest of Kyiv has deviated somewhat from schedule. In less deranged times, a European democracy menaced by Moscow might have welcomed the inauguration of a Republican president: Ronald Reagan did not stand before the Brandenburg Gate in 1987 and say “Mr Gorbachev, re: this wall, whatever.” But Ukraine cannot make any assumptions of such support where Donald Trump is concerned. Given his desire to force a swift resolution, Kyiv – and the rest of Europe – needs to start thinking about the best possible outcome that could be wrought from the present circumstances.

The vastly preferable conclusion to hostilities remains a complete collapse of Russian lines and/or a change of leadership in the Kremlin, prompting an end to this entire monstrous folly, as well as a richly deserved reckoning for Putin. But many more Ukrainian lives could be lost – and much more of its allies’ money spent – waiting for this to occur. However, if the imperative is to work with things as they are, there are some grounds for cautious optimism. The parameters of a ceasefire deal are not difficult to imagine. Russia would keep, more or less, what it holds but at a cost of hundreds of thousands of needless casualties, billions of squandered dollars, the reserves of whatever international respect it might previously have enjoyed and its president’s dwindling travel options, circumscribed as they now are by an icc arrest warrant. Nevertheless, few voices in Russia would dare dispute Putin’s claim of a tremendous victory.

The rest of Ukraine could edge towards the EU, though probably not into Nato. The model might be akin to post-1945 Germany, split between a democratic, progressive West – host to a hefty foreign military presence – and a depleted East, held hostage by Moscow. In the short term, this would at least end Ukraine’s horrendous suffering. In the long term, given that there is no record of people enjoying life under Russian dominion, we might be able to look forward to the day when the people of occupied Ukraine pull down whatever statues Russia cares to put up. —

Andrew Mueller is the host of ‘The Foreign Desk’ on Monocle Radio.

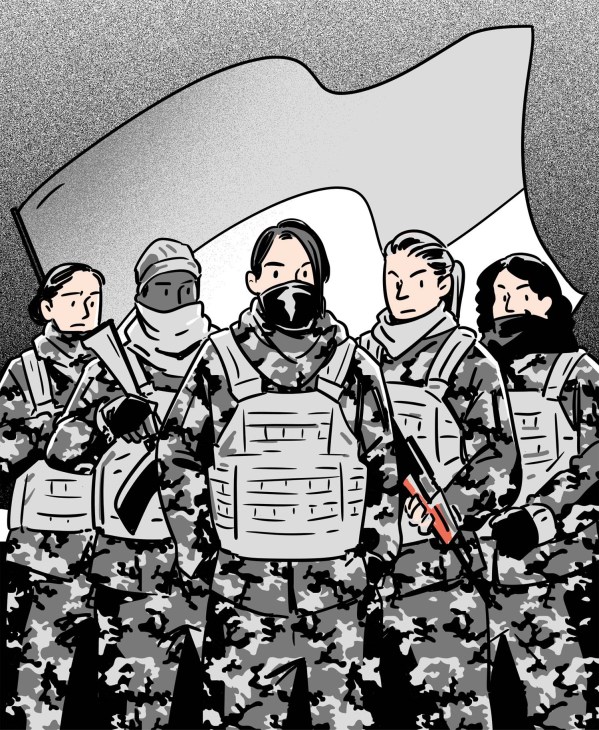

I don’t want to be a victim. But over the years of war in my country, I have realised that this isn’t possible without knowing how to defend myself and my family. If I couldn’t fire a gun or fight off an attacker in close combat here, I would be defenceless. I’m writing this from Kyiv before returning to the Ukrainian front line. I have realised that if feminism has taught us anything, it’s that women should never become easy prey – a lesson that feels all too relevant when Russian shells are exploding around me and my team in our trenches in the country’s east.

War returned to Ukraine in 2014. I became a mother the year before, just as Ukraine’s pro-European revolution was kicking into action. Pro-democracy protesters flooded the streets, calling for EU integration and an end to the country’s cosy ties with kleptocratic Russia, which was pulling us ever closer, back into its empire. Then, as it invaded, first annexing Crimea in the south before sending in its troops to occupy our eastern cities, towns and villages, I came to understand two things clearly. First, that our army desperately needed soldiers as open, state-sanctioned violence had made a comeback and was advancing towards our homes. Second, it wasn’t just men but also women who now had to learn how to protect themselves.

I have always respected the Israeli model of conscription. From a Ukrainian perspective, with all of the violence that our population has suffered in the past 100 years, it makes sense to have a level of basic military training for both men and women. We helped Europe to overcome the Nazis in the 20th century but Russia’s imperial evil was never defeated in the battles of the Second World War. And we are fighting its desire to annihilate our country now. Ukraine’s entire population has to be more than just willing to protect itself in the abstract: it also has to be trained to do so effectively in the real world.

Women can play an important role in defence. I first joined the Ukrainian army in 2019 as a paramedic; within a year, I signed up as a regular contract soldier. Soon I became a combat medic and took on reconnaissance in the Ukraine Marine Corps battalion, mastering how to pilot drones. In this time, I have fought alongside both men and women. I can confidently say that those women on the front lines today are, in my opinion, on average more motivated and determined than the men.

Of course, part of this is simply down to the fact that those I fought beside chose to enter the army – there is currently no conscription of women in Ukraine. Around the world, 21 countries include women in their conscription programmes, including three in Europe (Norway, Sweden and Denmark). But I have also witnessed how much better women can be at dealing with situations that men might shy away from. Take blood, for example – we see a lot of it on the battlefield, unfortunately. But perhaps because women encounter much more of it in our civilian lives, many are less scared to deal with it.

Women are also often more likely to be open about how they are feeling. We start conversations that men might otherwise avoid. This allows us to deal with stress more effectively. With rates of ptsd in Ukrainian society rising, it is paramount that we are all open about our experiences, both mental and physical. Some qualities that have been traditionally deigned feminine actually serve to complement many aspects of a soldier’s experience.

There are also so many women in the Ukrainian army who inspire both me and my male colleagues to keep fighting as part of a more skilful, modern army. Take my friend, Olena Bilozerska, for example. A writer and journalist in her civilian life, Bilozerska trained to be a sniper in 2014. She wrote about her experience as a servicewoman in her memoir Diary of an Illegal Soldier, which was published in 2020. And on the battlefield, her skill has been lauded by people all over the world, including US soldiers – a video of her working just 200 metres from the occupiers was published on YouTube and ended up going viral.

So, how might female conscription work? Perhaps some imagine that if women are included in the draft, society would face a crisis with no one left behind to look after children and the elderly. But there are always a certain number of people who would never be called up. Carers and single mothers would be taken off the list automatically in the same way that Ukrainian men with more than three children are today. We would need to be practical.

But leaving aside the issue of female conscription, I believe that we are leaving a large resource untapped. Many women who I have spoken to say that they support the idea of being called up and doing their bit. If they were to receive that letter in the post, they would gladly go. They are keen to help but they need the legitimacy of the state to justify their presence in units that might otherwise treat them with scepticism or as outliers.

Doing so would also bring a few lazy stereotypes into the crosshairs. We could show once and for all that women can be as strong and brave as men, if we only let them demonstrate their potential and legitimise their participation. It would be a golden opportunity to put patriarchal stereotypes to bed and impart a greater confidence in a truly equal society.

The threat of war might seem far away for many Western readers living in comfortable, safe countries. But my country’s situation and our overnight transition from a hopeful European democracy to a nation under violent attack has proved the old Latin saying right: if you want peace, prepare for war. And don’t leave us women behind.

About the writer:

Yaryna Chornohuz is a senior corporal in Ukraine’s army. She published her first book of poetry, How the War Circle Bends, in 2020. She was awarded the prestigious Taras Shevchenko National Prize in 2024 for her writing.