By this point in the summer, I’m sure you’re on top form when it comes to the dark arts of packing. For weekends, weddings and longer explorations of beaches, hills or cities, stowing the perfect amount of the right stuff is paramount. It’s a joy to revisit friends in Cap Ferret who, while job-smart in Geneva, are piratical rustics when in sight of the Atlantic, and we all lean happily into a little of the Bordeaux-hillbilly vibe that makes packing a cinch (as Phil Collins knew in 1985, there really is “no jacket required”). We’ve no doubt raised an eyebrow at other halves secreting a sixth pair of shoes in the last free corner of the that’s-meant-to-be-the-bloody-carry-on case.

Packing is a practice that elicits strong emotions. There is a belief in a correct path, the Right Way. It’s a moral issue. Packing light is packing best; we all know this. But doing it economically takes strength, resolve and practice. If you haven’t capsule-wardrobed your way out of some dark nights of the soul, well, pal, take it from me: a linen jacket with a decent lapel and a pair of white jeans can save you a lot of heartache.

Packing light means – and shows – that you’ve thought about it. You’ve done the work. Now you’re standing at the departure gate, looking fresh and unencumbered and, yes, you’re enjoying the fact that other people are gnashing their teeth in anguish as the stewardess gives her stern assessment of the size and weight of their suitcase. (And what is that hanging out of the side – a bra-strap?) Straight into the hold and no passing go.

You’d be right to think that packing-lightliness – like cleanliness – is next to godliness. It displays an understanding of and respect for notions of self-restraint, control, a higher order. It confers a feeling, when wheeling one’s case, similar to that offered by gazing at the paintings of the 17th-century Dutch master Pieter Jansz Saenredam’s cool oils of the hushed interiors and vaulted ceilings of the largest of the churches in Haarlem and Utrecht. The vast calm of “just right”. We glimpse clarity and communion. Grand design. We grasp the higher purpose and, in Room 14 of Rome’s Hotel Locarno, our socks are rolled perfectly into our canvas chukka boots in our elegantly trim suitcase. Hallelujah!

But there’s also something a little seamy about packing light. Could it signal the need to escape, if necessary – being able to get out fast? Could it mean a dash of danger? Assignations in the night? We might think of Sean Connery’s James Bond slipping a banknote to a liveried bellboy to retrieve his slim valise, after which we see our hero in black tie, wearing a summer suit, strutting poolside in trunks and then playing golf in a Pringle sweater and slacks, before jumping into his Lagonda in a Gieves three-piece. All in different shoes. That’s not a suitcase – it’s a department store! Maybe there is a little editorial sleight of hand in packing that parsimoniously.

For all this, as I write, I’m getting ready to spend the weekend at one of the closing music festivals of the waning British summer. I will be sleeping in a tent. Yeah: get you, Dickie Greenleaf. I’ve been packing and re-packing for days and have more luggage than Elton and Mariah could summon for a camp glitzathon of a world tour. My efforts are a disgrace to everything that I hold dear. Think of me in your Greek villa with your six pairs of shoes. And sod Phil’s advice: I packed a jacket, just in case.

Heading away? The Monocle Shop has suitcases, travel organisers and luggage tags to help you make all of this as easy as possible. And there’s a sale on.

Read next: The only clothes you need for a short-haul sojourn

Crowds lined up at the Iconsiam shopping centre in Bangkok this month not for Louis Vuitton or Prada but for a dopamine-fuelled buying frenzy at Pop Mart, the Beijing-based collectibles giant that opened its largest global flagship in the Thai capital. Across town at Centralworld, a pop-up from premium bag brand Songmont – a cult favourite in China – is enjoying a similarly warm welcome at its first overseas outpost. Its €500 “Gather” handbags aren’t in the same league as Hermès or Chanel but they’re a far cry from the fast fashion of Shein or Temu. For the mid-career professionals queueing up, the brand’s Beijing roots are part of the appeal.

Though Songmont wears its Chinese heritage lightly, it is leaning into pan-Asian storytelling. The ancient silk road (rather than president Xi Jinping’s revival plan) features heavily in slick marketing campaigns pairing idyllic pastoral scenes with the products’ minimalist design. One video shows smiling seamstresses in colourful, artisanal clothing working on the sunny steppes of what could be Inner Mongolia.

The arrival of Chinese retail brands with better products, richer narratives and accessible luxury pricing is happening both across Southeast Asia and across segments. What stylish women are carrying around Shanghai is now considered cool and covetable by their peers from Jakarta to Singapore. Meanwhile, men are opening their wallets for Chinese technical- and active-wear from the likes of Benlai and Beneunder. Both are strong on simple wardrobe staples – a potential concern for the Lululemons of the world. Even the mighty Uniqlo could need to limber up for a rare bit of competition.

Chinese entrepreneurs and creatives now talk obsessively about intellectual property as a genuine asset to be developed and protected. Meanwhile consumers across Asia are fully aware that a lot of the international brands that they buy are made in Chinese factories, despite the lengths that some firms and industries go to disguise it. After decades of outsourcing to China, it’s hardly surprising that the best technical and manufacturing expertise is found there.

Of course, only time will tell whether these Chinese brands have staying power. Songmont’s influencer-fuelled buzz might fade away along with the queues at Pop Mart. But there are hundreds of other brands in China queuing up to go global. Brand China is cresting and we’ve already seen this play out in social media, skincare, electric cars and even coffee. The only thing that has gone out of fashion this year is the daft talk about “peak China”.

Frankly, it’s only a matter of time before US shopping malls and European high streets start to see a similar influx of new retail tenants from China and increased competition for prime real estate. For a sign of what’s coming down the track, watch out for the veteran Chinese sportswear label Anta – a classic case study of Brand China’s long march from ridicule to respectability. For the best part of this century Anta has built up a huge network of pretty lacklustre stores in second- and third-tier cities around China. Good business domestically but Chinese kids weren’t setting off for school or university in the US with a pair of Anta shoes packed proudly in their suitcases. Previously, China’s answer to Nike and Adidas had to buy global credibility the old-fashioned way – by acquiring Western brands such as Arc’teryx and Salomon. Not any more. Now Anta is launching shoes with famous US athletes and getting ready to open its first standalone US shop in, of all places, Beverly Hills.

If Chinese basketball trainers and leather handbags do take off in the US, they will be a lot harder than Tiktok or BYD for the White House to ban or shut out on national security grounds.

The fervour for New Nordic cuisine has swept across Tokyo over the past 10 years. In the polished wake of Noma’s two Kyoto pop-ups, it’s easy to assume that Nordic culinary influence in Japan is a fairly recent affair. But decades before the phrase “Japandi” was coined or the first foraged lichen was plated in a minimalist ceramic bowl, two restaurants quietly shaped Japan’s early impressions of Nordic dining: Scandia in Yokohama and Lilla Dalarna in Tokyo.

These pioneering establishments opened in suitably muted fashion: no PR rollouts or brand tie-ins, just a simple mission to offer warm, Scandinavian-style hospitality and culinary curiosity. Both restaurants are still in business, and both have deeply personal origin stories.

Scandia opened in 1963 and sits just minutes from Yokohama’s bustling port. Tucked into a handsome mid-century brick building, the restaurant has a formal upstairs dining room with white linen and port-glass chandeliers, and a more casual first-floor “Garden” bistro with lace curtains and views of Yamashita Park.

At night, Scandia glows like a perfectly preserved artifact of postwar optimism. The building’s brick façade is flanked by red striped awnings and bold neon signage in royal blue and crimson mid-century type. Through the windows is warm table light and shadowy silhouettes; the kind of scene that promises old-school civility and a second helping of lobster. Scandia projects quiet grandeur as opposed to ostentation, it’s a beacon of understated Western elegance from another era.

My party of six climb a red-carpeted staircase lined with carved wooden reliefs depicting scenes of Nordic folklore before tucking into the signature “smörgåsbord deluxe dinner” – a gleaming procession of scalloped crystal platters featuring herring in vinegar and onion, salmon mousse on toast, cured meats, cold lobster, escargot and seafood aspic. All were carefully arranged with lemon wedges and herbs, curled garnishes punctuated the bounty. The tableware, meanwhile, bears tiny painted coats of arms – Swedish blue and yellow, Danish red, and Norwegian red and blue.

I order a smoked salmon appetiser with dill and sour cream, and a filet steak with Madeira sauce. The flavours are creamy, herbal, gently sweet and the plating feels akin to a Scandinavian consulate luncheon circa 1983. Though Scandia’s 91-year-old founder, Yaeko Hamada, no longer gives interviews, her presence still anchors the place. “We have been operating the business with the same motto of ‘customer first’ since 1963,” she notes in the restaurant’s printed mission statement. The executive chef, Hiroyuki Arakawa, echoes this sentiment: “The smiles of satisfied customers spread joy to those around them.”

In contrast, Lilla Dalarna was founded in 1979 and channels a humbler, homespun warmth. It was opened by Seiichi Okubo, a Japanese chef who travelled to Sweden via the Trans-Siberian Railway in the 1960s, and remained there for more than a decade – learning the language, working in kitchens and absorbing the Nordic way of life. Upon returning to Japan, he opened a restaurant of his own that sought to share the calming, communal spirit of Scandinavian hospitality. Lilla Dalarna was originally located in Nishi-Ogikubo, a quiet neighbourhood in western Tokyo, before relocating to its current spot in Roppongi, where it serves curious locals, the Nordic embassies and homesick Scandinavians.

A few steps from the Roppongi Hills development, up a discreet stairwell tucked behind a Spanish bar, Lilla Dalarna feels like stepping into a Scandinavian countryside retreat. As a native of the Dalarna region, I recognise some of the accents of the place: Nordic plates in pale blue floral patterns, antique copper pots and cosy lighting redolent of summer evenings.

We started with three kinds of pickled herring and slices of smoked salmon with dill, then shared a bubbling dish of Jansson’s frestelse (temptation), which is a beloved Swedish casserole of potatoes, onions, cream and anchovies. For mains, we chose the signature Swedish meatballs in cream sauce, served with mashed potatoes, lingonberry jam and pickled cucumber. Each plate felt as though it had been summoned from a Nordic family cookbook; heartfelt, gently executed and never fussy. Lilla Dalarna captures the spirit of my homeland with sincerity and care.

Now run by Okubo’s protégé, Chef Endo Yoshio, Lilla Dalarna has evolved with the times while staying true to its roots. “I’ve been part of the restaurant for half its history, and its role in Japanese society has definitely changed”, Endo says. In the early years, Swedish cuisine was largely unknown in Japan. By the 1990s, when Endo joined the kitchen, Japan had become more outward-facing. “We started seeing guests who came in already familiar with Swedish values, who respected what the Nordics stood for.” Lilla Dalarna responded by layering in more tradition: crayfish menus, seasonal semla buns, even cultural tie-ins with embassies and Scandinavian holidays. “And still,” Yoshio says, “our goal has always been to offer a comfortable space and a menu that guests return to.”

Neither Scandia nor Lilla Dalarna followed the path of New Nordic cuisine. You won’t find pine-needle oil or dehydrated sea buckthorn on the menus. Instead, what these restaurants offer is something arguably more radical in 2025: continuity, modesty and an unwavering sense of place. They are neither themed eateries nor nostalgia traps. They are lived-in institutions, where Nordic food has been translated through time, geography and local affection.

At a moment when Scandinavian style in Japan is often flattened into a mood board of wooden design minimalism, Scandia and Lilla Dalarna remind us that Nordic-Japanese culinary exchange began with travel, curiosity and two restaurants that simply kept showing up, year after year, herring plate after herring plate.

Read next: How fiddly New Nordic cuisine is falling out of favour on its home turf

The run-up to the tête-à-tête between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin in Alaska begged the question: where? While the general co-ordinates were known – only Anchorage’s runways can accommodate both Air Force One and the Russian presidential plane – envoys from the US State Department and Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs likely struggled to pin down an exact setting before settling on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson.

That’s because, to put it bluntly, Anchorage doesn’t inspire. The state’s largest city was levelled by a 9.2-magnitude earthquake in 1964 and was quickly rebuilt without grace. For starters, there’s only one marquee lodging property: Hotel Captain Cook. While the interior boasts some suitable nooks for hushed diplomatic chats and local touches convey a sense of place (try the reindeer sausage at breakfast), the property consists of a pair of uninspiring towers erected in the 1960s and 1970s.

The exclusive upper floors were deemed good enough for Barack Obama to spend the night there in 2015 and Xi Jinping to dine with leaders in 2017, while US and Chinese officials held testy talks there in 2021. The Captain Cook could work in a pinch for the Trump-Putin summit but it’s hardly the elegant Capella Singapore, where a plaque commemorates Trump and Kim Jong-un’s 2018 handshake.

Putin isn’t the first head of state to have been given the Alaskan hangar treatment. Richard Nixon greeted Emperor Hirohito at Elmendorf Air Base in 1971 and Ronald Reagan met Pope John Paul II at the Fairbanks Airport in 1984; both are further indications of a lack of suitable venues in Alaska. Trump and Putin could commandeer the recently renovated Alaska Airlines lounge at Ted Stevens International Airport for a quick in-and-out but such a makeshift solution would only further undercut the state’s diplomatic aspirations.

While much of the world puzzles over the choice of Alaska over rising mediating stars including Istanbul, Doha and Riyadh, the state champions its strategic geopolitical location as the US Arctic foothold. Newer buildings such as the Dena’ina Convention Center, designed by Seattle-based LMN, have boosted the profile of the annual Arctic Encounter Symposium that was held recently. But it’s hardly an architectural landmark akin to other hubs of diplomatic dialogue. Take Reykjavik’s Harpa Concert Hall, home to the Arctic Circle Assembly, or Tromsø’s Arctic Cathedral. Even David Chipperfield’s Anchorage Museum deserves praise.

Alaskan civic leaders need to build on these Arctic architectural legacies to make good on their conviction that the midpoint between North America and Eurasia could serve as the fulcrum for negotiations in the new era of great-power politics. That Russian and Chinese officials can travel there without crossing into foreign airspace is both practical and symbolic, given concerns about International Criminal Court jurisdiction and the desire to exclude European participation.

Plus, there’s powerful bilateral symbolism: Moscow sold the territory to the US in 1867 and maintains multiple Russian Orthodox religious buildings in Alaska as heritage sites. But whatever its period charms, Trump and Putin are unlikely to meet in a restored sod roof blockhouse built by the Russian-American Company in 1841 as a fur-trading outpost.

What world leaders need is a setting where inspiring design fosters healthy dialogue. In 1986, Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev sat down in Reykjavik at Höfði, an intimate early-20th-century house, and began thawing the Cold War. Two years ago, Joe Biden and Xi Jinping strolled a bucolic country estate outside San Francisco, signalling a dialling down of Sino-American tensions.

Architects take note. Alaska needs a new blueprint for success: a cool, cosy enclave blending the best of Pacific Northwest modernism and contemporary Arctic design sensibilities that can elevate the state to a Geneva-on-the-Inlet. Today’s talks might be built on sand but, regardless, Anchorage falls short.

Gregory Scruggs is Monocle’s Seattle correspondent and has reported frequently from Alaska. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

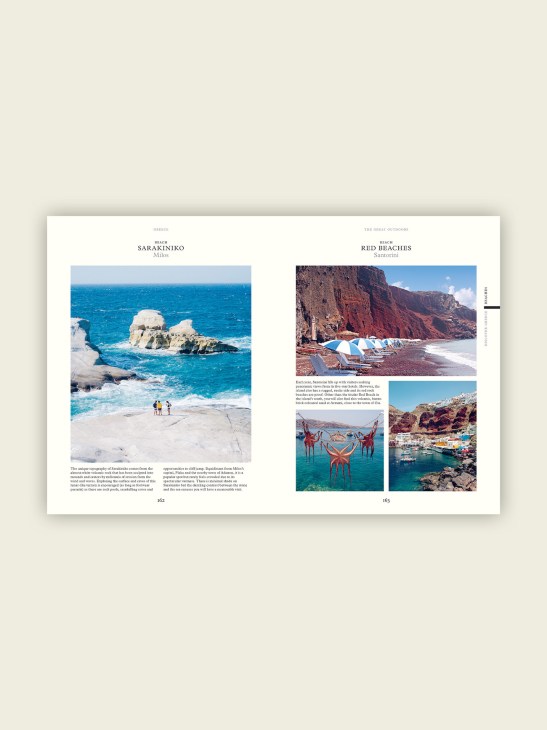

1.

Greece: The Monocle Handbook

Making time for a weekend trip to the Hellenic world or planning to stay a little longer? We present our most treasured recommendations across the country, from rural tavernas to island retreats and Arcadian ski slopes. We’ve also scoured the country for its most skilled artisans, so take a trip and dive into our guide to Greek fashion, food and design. Plus: for those looking to put down roots we reveal the places to set up a home, the clubs to join and the architects to consult. It’s time to explore this ancient country afresh.

Buy a copy here

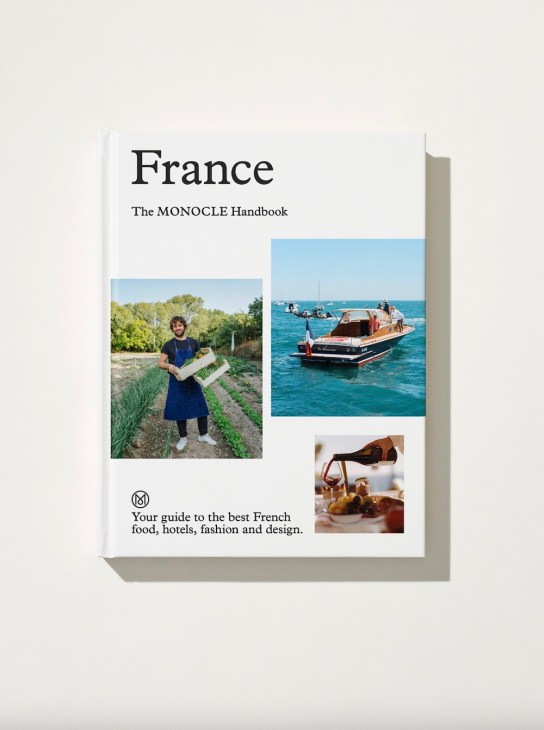

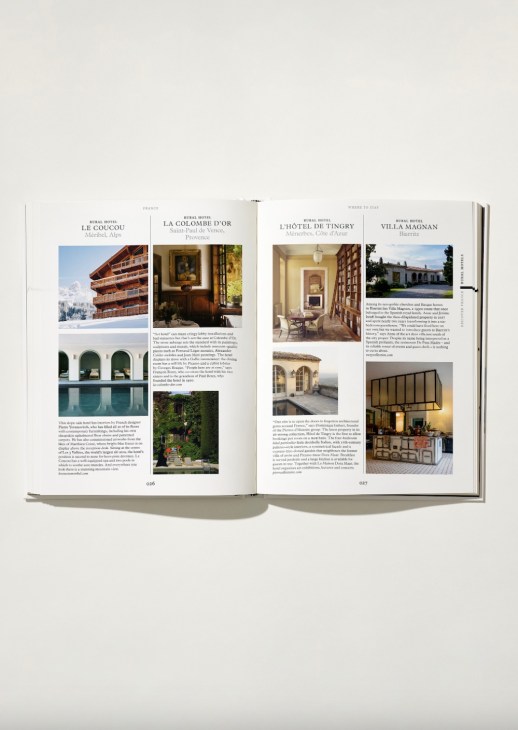

2.

France: The Monocle Handbook

Allow us to take you on a tour of our most cherished Gallic spots. We have traversed the mainland to scout out the creme de la creme of the nation’s bounty.

Come with us to Marseille and Montpellier, Biarritz and Brittany, with stop-offs in the Alps and along the rugged coast of Corsica. Break bread at both new and established bistros, visit luxury ateliers with a discerning eye for design and check in to Paris’s most storied hotels and metropolitan boltholes. Plus: we toast the nation’s vineyards, the cultural spots honouring France’s artistic heritage and the plucky retailers setting up shop in the country’s second cities. Fancy staying a while longer? We’ll take you through the places in which to linger, should you wish to put down roots. France is the world’s most visited country, and for good reason.

Buy a copy here

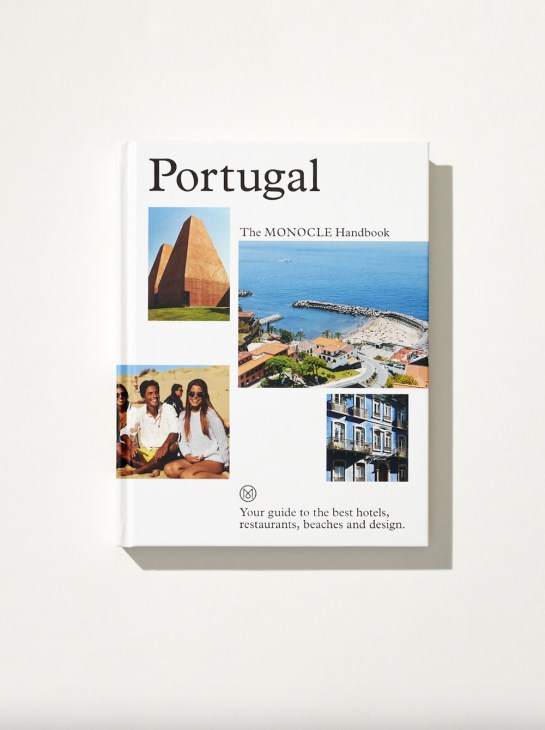

3.

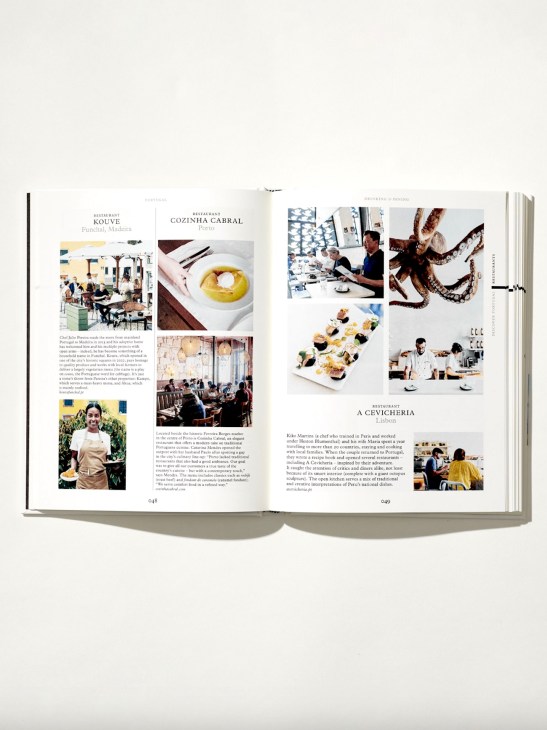

Portugal: The Monocle Handbook

A practical guide that will introduce you to the best the country has to offer as we present our favourite spots across the country. We’ve travelled from north to south (via the islands) to find innovative retailers and traditional ateliers, the chefs turning out the tastiest dishes and the sleekest hotels – not to mention undiscovered beaches and world-leading cultural venues. We even reveal the best neighbourhoods to invest in should you wish to put down roots in this sunny nation, plus the plucky entrepreneurs who’ve already made the move. It’s time to pack your bags for Portugal.

Buy a copy here

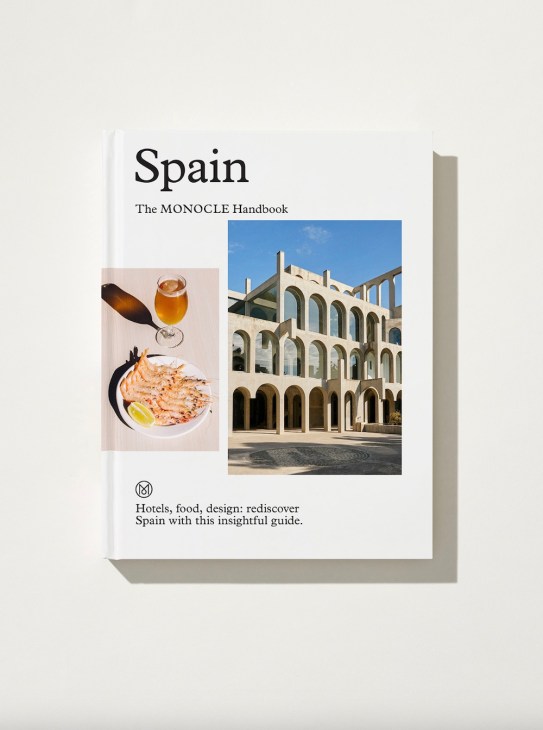

4.

Spain: The Monocle Handbook

This sunny book looks beyond the tourist haunts to present Monocle’s favourite spots across from Madrid and Malaga to the Balearic and Canary Islands. Discover innovative retailers, culinary hotspots and cool hotels, as well as leading museums and galleries – and, of course, a beach or two. We also introduce the smartest neighbourhoods to relocate to, plus the design contacts to know, with advice from a few plucky entrepreneurs who have already set up shop. What are you waiting for? It’s time to pack your bags and discover this varied nation afresh.

Buy a copy here

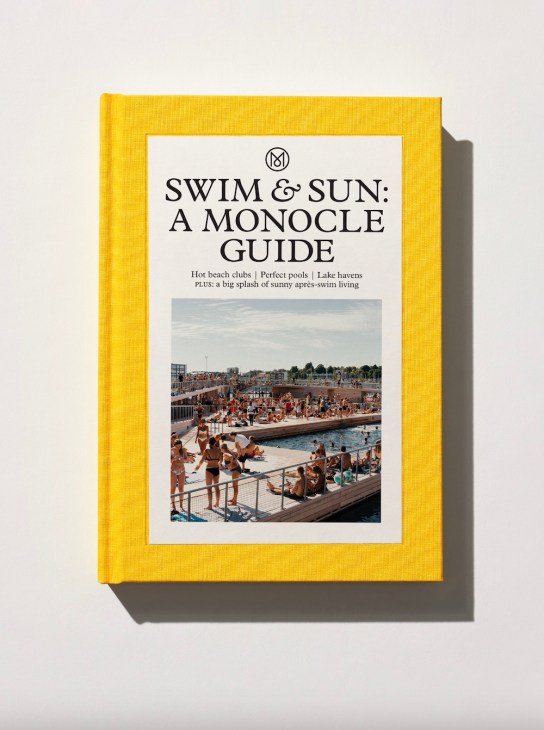

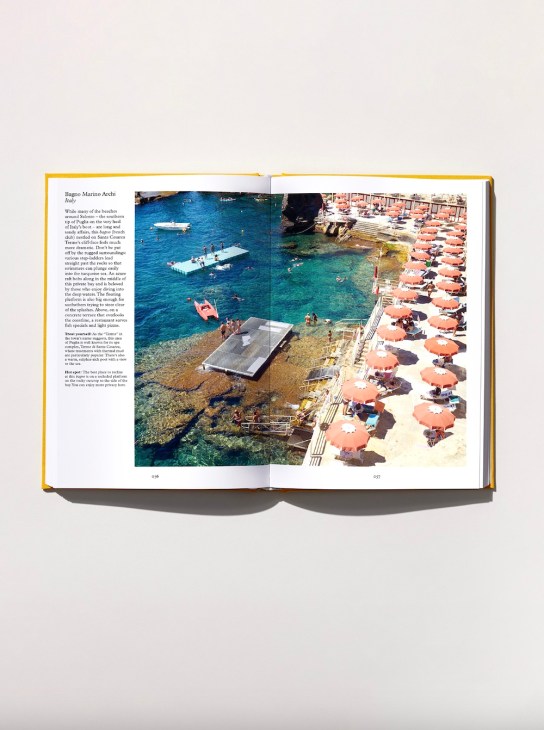

5.

Swim & Sun

Here you’ll find our pick of the places in which to cool off when the mercury rises and plenty to get you dreaming about your next dip. We celebrate the joys of diving into the ocean, leaping into a river and allowing your limbs to stretch – and your mind to clear – as you simply swim. In its visually stunning pages, the guide celebrates the sunny pleasures on offer at our favourite beach clubs, urban pools and lakeside bathing spots. Pick up a copy and jump in. The water’s perfect.

Buy a copy here