Inside the fighter-jet school where virtual technology is your wingman

How augmented reality is helping to prepare a new generation of pilots for aerial combat.

Wishing a fighter pilot a good flight isn’t the done thing, apparently. Stefano Centioni, a former Italian Air Force (IAF) pilot who now works for the country’s largest defence contractor, Leonardo, winces at the suggestion. “That’s the sort of thing that you say to a Ryanair pilot,” he says. We’re at the International Flight Training School (IFTS) in Sardinia, a collaboration between the public and private sectors that is aiming to become top gun in the niche of fighter-pilot training. The school is based in the IAF’s Decimomannu Air Base, nestled in undulating scrubland a short drive from the city of Cagliari. As Europe works to scale up its arms-production capabilities in a bid to wean itself off its over-reliance on the US, Leonardo is expected to benefit. Currently Europe’s third-largest defence company, it is branching out into new areas, from aerospace to training, which is where IFTS comes in. The array of national flags flapping in the breeze in front of the reception indicates how many nationalities make up the facility’s student and teacher corps, which are as diverse as a Sardinian beach in summer. Opened in July 2022, the facility cost Leonardo more than €200m to build, an investment that the company hopes will be rewarded when pilots return to their home countries waxing lyrical about Italian technology and expertise.

Centioni, whose blue jumpsuit signifies his affiliation with Leonardo, is the school’s head of flight training organisation. Here, instructors come from both the private sector and the military. The IAF handles areas such as the syllabus, training and testing, while Leonardo – in partnership with a Canadian company called cae that specialises in flight simulation – looks after logistics, planes and maintenance. The school’s mix of flight time and computer-based training has been popular. Teaching is done in English and, to date, 13 nations have sent students for the nine-month course, including Spain, the Netherlands, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Japan and Singapore.

The IFTS moved from Puglia, where it was originally based, to Sardinia to take advantage of the island’s larger airspace. When Monocle visits, a site has been identified for two new housing blocks that are scheduled to be finished by the end of 2025, adding 40 units to the 58 that already exist for non-Italian cadets – a sign that the IFTS is currently oversubscribed. For Lieutenant Colonel Marcello D’Ippolito, the school’s commander, dressed in green to show he is still in the armed forces, its success is down to know-how. “This is the world’s most advanced fighter-pilot school,” he says. “The quality of Italian training is accompanied by another field of Italian excellence: defence, through Leonardo. Excellence plus excellence.”

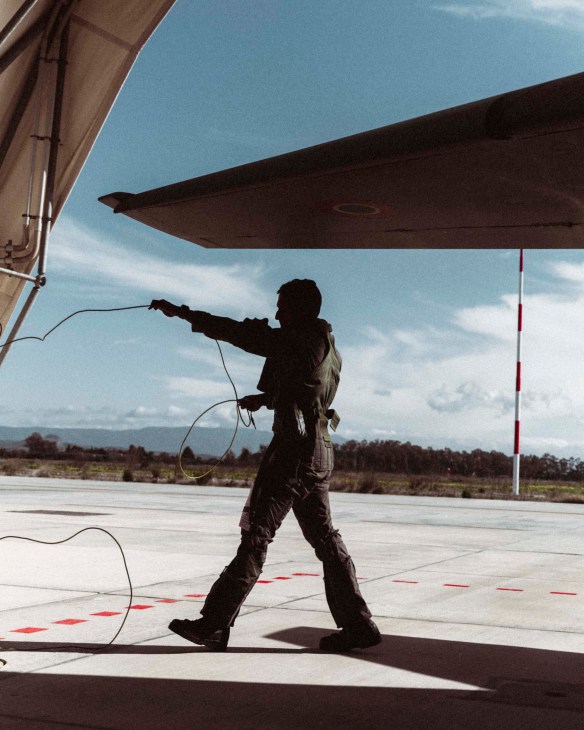

The ace up the IFTS’s sleeve is its aircraft: Leonardo’s twin-engine, tandem-seat M-346 AJT, built with training in mind. Released in 2013, it’s both technologically advanced and well tested. When students arrive in Sardinia, they already have their military wings but haven’t yet progressed to flying a jet. Monocle heads out onto the tarmac in a fleet of black Mercedes-Benz vans with a small group of international students and teachers for one of the 35 mock missions that fly from the school every day. Everyone is wearing their standard-issue flight clothing, which self-inflates inside the craft when necessary, putting pressure on the body to prevent G-force-induced blackouts. Every pilot also has a survival kit that includes water, chocolate and a radio.

A pair of jets taxi to their takeoff positions. There’s the smell of fuel in the air; a heat haze hovers over the asphalt and the roar of the engines bounces off the nearby maintenance building. Soon the aircraft are up and away.

“When you come here, the most beautiful thing that you see is the plane,” says Centioni, who is one of 40 teachers at the school. “It’s great but there’s a whole system of simulation connected to it too.” IFTS instructors are keen to point out the benefits of the LVC network, which stands for “live, virtual and constructive”. Alongside the real and the simulated components of their training (cadets split their time evenly between the two after a first month spent entirely on the ground), there’s the “constructive” part, which involves teachers sending virtual enemies from a control room to the radar of a real plane or to simulators. The ability to have war games of this multi-modal nature is a key advantage.

Centioni guides Monocle around the complex, showing off the three levels of the flight-simulation trainer. The entry level is full of students sitting behind screens wearing headphones and toggling HOTAS (hands on throttle and stick) controls, just as they would in an aircraft. The cost at this level is low, says Centioni, and students can come here whenever they want to practise, using swipe cards for entry. The second level, which needs to be booked with a teacher, involves a cockpit that is a replica of a real fighter jet’s. The final stage, which Monocle tries, is a capsule that closes around the trainee featuring a 360-degree screen. Though the simulator remains fixed to the ground, it fools the brain as the horizon shifts, inducing dizziness in novices. “Your stress levels go up,” says Centioni. “But that’s positive as it’s linked to performance.”

The IFT’s pitch to air forces is that they’ll save money in the long run if they send their pilots here. It’s a case that some of the establishment’s top brass make to Monocle over a buffet lunch in the school canteen, which includes a Middle Eastern food corner and plenty of international cuisines to cater for the school’s diverse intake. “Because other nations are using older trainers, there are things that pilots can’t practise until [much later] so they end up spending a lot more,” says Giovanni Basile, the managing director of Advanced Jet Training, the joint venture created by Leonardo and CAE. The M-346 allows students to practise things such as laser-guided bombing and dogfighting on a dedicated training aircraft earlier in their period of instruction than many other programmes. The US, which doesn’t currently send students to the IFTS, trains its pilots on the T-38 Talon, a jet first unveiled in the 1950s that doesn’t have the same capabilities. Boeing’s next-generation T-7A Red Hawk is on its way, with five delivered to the US Air Force so far, but there have been problems and delays. The UK, meanwhile, has retired most of its Hawk T2 trainers, which date back to the 1970s, and sends some of its young guns to Sardinia.

Monocle heads over to one of the student accommodation blocks which, with its front-desk reception, feels a little like a hotel. We visit the apartment of James (students’ surnames can’t be published for security reasons), a trainee pilot from the UK whose room is decorated with a Lego model of Nasa’s Discovery space shuttle and a thirsty-looking pot plant. Like all of the students we meet, James is happy to be doing what he sees as important to his training. He says that the M-346 is fast and manoeuvrable, with fly-by-wire controls that make it easy to use. “The jump to get to where we are now has been bigger [than in more conventional pilot training],” he says. “But from here to a front-line jet, it’s smaller.” As Stefano Centioni describes it, “It’s like going from a BMW to a Mercedes.”

Despite recent moves by the UK and EU to increase defence spending, some nations have sought to make savings by opting out of the advanced jet-training phase and having cadets jump from a simple turboprop aircraft to a combat-ready supersonic jet – which has led to concerns over their lack of airmanship. “The advantage that Western forces have over our adversaries is arguably not technology but the fact that we train our pilots much better,” says Justin Bronk, a senior research fellow at London’s Royal United Services Institute. “Skimping on training risks throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

That’s where the IFTS believes that it can play a crucial role. “We are the first people using an advanced trainer to manage complexity,” says Colonel Gianfranco Liccardo, commander of the 61st Wing Air Base in Puglia that the IFTS belongs to. “We have years of competitive advantage.” Still, Liccardo recognises that other nations will catch up sooner or later, which is why the school needs to stay ahead of the pack. Spain, for example, has already signed a memorandum of agreement with Turkey to receive 24 Hürjet advanced trainers from Turkish Aerospace Industries; deliveries could start in 2028. Centioni agrees. “Nokia and Motorola thought that they were the best, then Apple arrived,” he says. “We don’t want that.”

The IFTS’s plans to stay relevant include taking the augmented-reality training experience to the next level by having a hologram of virtual enemy jets appearing in a pilot’s helmet vision – an innovation that Leonardo is working on with US company Red 6. There are also plans to update the M-346 with a “Block 20” configuration that will include new digital and artificial-intelligence features. It isn’t just the global reputation of Italy’s defence capabilities that’s at stake in all of this. There’s also a bottom line to serve, as you would expect given that one of the IFTS’s partners is a for-profit defence company (albeit one whose largest shareholder is the Italian government). Giuseppe Recchia, the head of Leonardo’s IFTS business unit, sits down with Monocle in the school’s ground-floor café, near a sign that reads “Our hearts have wings”. He says that nations have bought M-346 trainers off the back of their ifts experience, including Singapore and Qatar; at the end of last year, Austria purchased 12 of the combat-ready Fighter Attack versions. However, Leonardo also sees another business opportunity in the “huge demand for training worldwide”, says Recchia. The school is part of the company’s move into being what he calls a “solutions provider”. With European defence firms still dwarfed by their US counterparts, such as Lockheed Martin and RTX, Leonardo’s services arm is part of its plan to be an integral EU defence player, a move laid out in the five-year plan that it published in 2024. The figures are heading in the right direction. Last year’s revenue was up 16 per cent on 2023’s at €17.8bn and the trend is expected to continue. “We have 12 international customers at the school,” says Recchia. “If they appreciate our level of service, we can strengthen our reputation worldwide.”

As well as the Sardinian base expansion, there’s the possibility of other campuses in different parts of the world in the future. For now, the focus is on keeping the current facility running smoothly. The biggest concern for students is learning to spell everyone’s names, says a Canadian cadet called Ben, who tells Monocle that he is following in his fighter-pilot father’s footsteps. He recently had his first M-346 flight, accompanied by a German instructor. “Because you eat, sleep, train and work out here, it removes all other obstacles,” he says, sitting in the lobby of his housing block. “That means you can focus on being your best.”

IFTS in numbers

13 countries have sent students to train here.

130,000 sq m: Size of the campus.

70: Number of students.

40 instructors from 12 countries currently oversee the course.

600-700: The average number of flight missions per month.

7: Total number of basketball and padel-tennis courts on the site.

25 metres: The length of the indoor swimming pool.

Better together

Leonardo has earmarked several strategic partnerships as part of its growth plan, including building tanks with Germany’s Rheinmetall in a joint venture. But most significant is the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), a collaboration between Leonardo, the UK’s bae Systems and Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. The three companies aim to deliver a next-generation stealth fighter jet by 2035. An agreement was reached in 2022 and a GCAP company was formed at the end of last year, with plans for a UK headquarters. The plane will make use of supercomputing, artificial intelligence and cyber-resilient data links, among other technologies, with an initial order of 350 expected by 2035. GCAP isn’t the only programme of its kind. France, Germany and Spain have their own jet collaboration called Future Combat Air System, with a delivery date set for 2040.