How Dick Cheney made vice-presidency dangerous

Dick Cheney turned a seemingly insignificant job into the most powerful office in the world, secretly driving controversial tactics and helping to lead the US ‘war on terror’.

The vice-presidency of the United States is one of the strangest jobs in global politics. The holder of the office is all at once extremely close to awesome power, yet miles away from any power at all. So long as the occupant of the White House stays healthy and lucky, the vice-president is usually a ceremonial eunuch, sent on diplomatic visits to ghastly places that the president can’t be bothered with, engaged to speak at state fairs teeming with uncomprehending riff-raff or confined to their opulent quarters, wistfully reading biographies of John Wilkes Booth.

Many who have done the job have hated it. John Adams, the very first vice-president, griped that “my country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” John Nance Garner, vice-president to Franklin D Roosevelt, legendarily growled that the position was “not worth a bucket of warm spit”; he might not actually have said “spit”. Thomas Marshall, vice-president to Woodrow Wilson, is credited with a joke about two brothers, one who ran away to sea, one who became vice-president, and from neither of whom was any more heard.

But Richard Bruce Cheney, who died today at the age of 84, was never going to be one of those vice-presidents. He was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, on 30 January 1941 and raised substantially in Casper, Wyoming. He was a bright but wayward young man – smart enough to get into Yale, not disciplined enough to stay there and a repeat offender of traffic violations. He was, like many middle-class young American men, a serial dodger of the Vietnam draft – in his case by being an apparently perpetual student, then a married man before 26 and then a father. It was waspishly noted that his first daughter, Elizabeth, later a politician herself, was born nine months and two days after the draft was extended to married men without children.

Cheney’s ascent of the political greasy pole began properly in 1969. Having finally completed his political-science studies, he became an intern to Wisconsin’s Republican congressman William Steiger. Shortly afterwards, he began making himself useful to former Illinois congressman Donald Rumsfeld, the then-counselor to president Richard M Nixon.

Cheney acquired a reputation as an efficient functionary and survived his service in Nixon’s administration unscathed by its implosion following the Watergate scandal – so did his mentor, Donald Rumsfeld, who had been serving as ambassador to Nato in Brussels. Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, engaged Rumsfeld as White House chief of staff with Cheney as his deputy. When Rumsfeld was appointed secretary of defence, Cheney inherited the chief of staff’s job – gatekeeper to the Oval Office.

Cheney did not keep it long. Ford lost the 1976 presidential election to Jimmy Carter but Cheney was not done with politics. In 1978 he won Wyoming’s only seat in the House of Representatives. He was re-elected five times and rose to become House minority whip and chair of the House Republican conference. In 1989, president George HW Bush named him secretary of defence, in which role Cheney oversaw the US invasion of Panama in late 1989 and the US-led eviction of Iraqi forces from Kuwait in early 1991.

Cheney’s progress in politics was interrupted by Bush’s loss of the 1992 presidential election. There was some vague talk of Cheney seeking the Republican nomination himself someday but three key factors always weighed against it. His health was rickety: he suffered recurrent heart attacks from his late thirties onwards; he would have a heart transplant in 2012. He was protective of his second daughter, Mary, a gay woman whose private life would have become public. And he was a notably dismal public speaker.

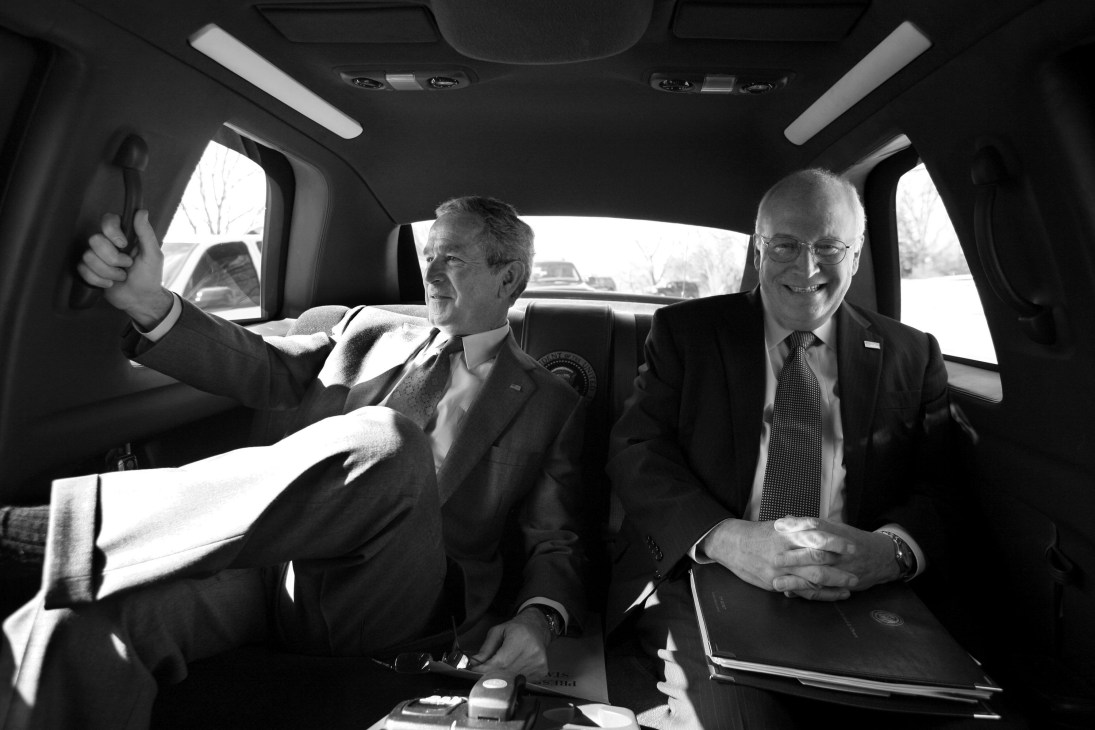

Cheney spent much of the 1990s making money, as CEO of the colossal energy-services multinational Halliburton. He was summoned back to public office by Texas governor George W Bush, seeking to bolster his own tilt at the presidency by putting an experienced heavyweight on the ticket. If Cheney, once Bush’s narrow victory was confirmed, had doubts about what he might make of the vice-presidency, events – specifically, the events of September 11, 2001 – clarified matters for him.

Significantly at Cheney’s urging, Bush presented the pair of them to the world – to the Middle East especially – as bad cop and worse cop. While Bush gave the jut-jawed speeches, Cheney seethed in an assortment of bunkers, scheming to vanquish enemies real, potential and altogether imaginary. He was a significant architect of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, amplifying intelligence about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction which was widely believed dubious at the time and eventually proved entirely bogus. He was an aggressive enthusiast of the brutal – and debatably effective – tactics that became known by such sinister euphemisms as “enhanced interrogation” and “extraordinary rendition”.

Cheney’s vice-presidency was a rebuke to that hefty lexicon of jokes about the impotence of the office: he made himself the most powerful person ever to inhabit it and, for the first eight years of the 21st century, one of the most powerful people on Earth. It is arguable that some of what he did with that power, even if furtively and unaccountably, made his fellow citizens safer but that presents the difficulty of measuring terror attacks that never happened. It is certain, however, that Dick Cheney played a key role in unleashing events that grievously and lastingly damaged America’s reputation and moral authority. He left office with an approval rating among his fellow Americans of 13 percent, probably not all that far in front of Osama bin Laden.