Re-examining migration beyond the headlines: Why do people move?

We quiz a migration minister, reveal why African passports are desirable for the super-rich and find out which nations are short of architects and fishmongers.

Of the many issues roiling our politics, migration appears to be the most important, at least to voters. In large Western countries, most of which have high inward migration, opposition to it is upending the political status quo, resulting in the rapid rise of right-wing populist parties whose raison d’être is to severely limit the numbers of people coming in. Even in smaller nations without large immigrant populations and more of a tradition of emigration than immigration, such as Hungary and Poland, the issue has come to dominate politics.

Whether they are on the right or left, political parties feel that they must take a position. In places such as the UK, France and Germany, historically centre-left parties have largely followed their traditional working-class voters to the right, aping the policies and rhetoric of the insurgent populists. This has created an environment in which it feels as though the only stance to take on immigration is to be against it. And yet, this same bipartisan position is being taken in a world that is more mobile than ever – with people able (and desirous) to travel across borders in record numbers. Adding to the cognitive dissonance is the reality that humans are by nature migratory and migration has defined our history; indeed, countries such as the US, now the leading voice of international anti-immigration, were formed by it.

It would not be radical to suggest that the subject is not as straightforward as it is made out to be. Beyond the headlines of out-of-control irregular migration and voter dissatisfaction, millions of people successfully emigrate every year and many governments welcome them with open arms.

Throughout Monocle’s February edition, we explore this hottest of hot-button issues. Here, we survey who is moving and why, and list 10 countries that are courting immigrants in specific professions (it might surprise you). Then we look at the wealthier people (many from rich countries) who are acquiring citizenships (many of poor countries) using financial means and their reasons for doing so. Finally, we travel to Madrid to meet Spain’s migration minister and discuss why her government is setting high targets for the number of people who it wants to attract.

Putting down roots

It’s not all about money.

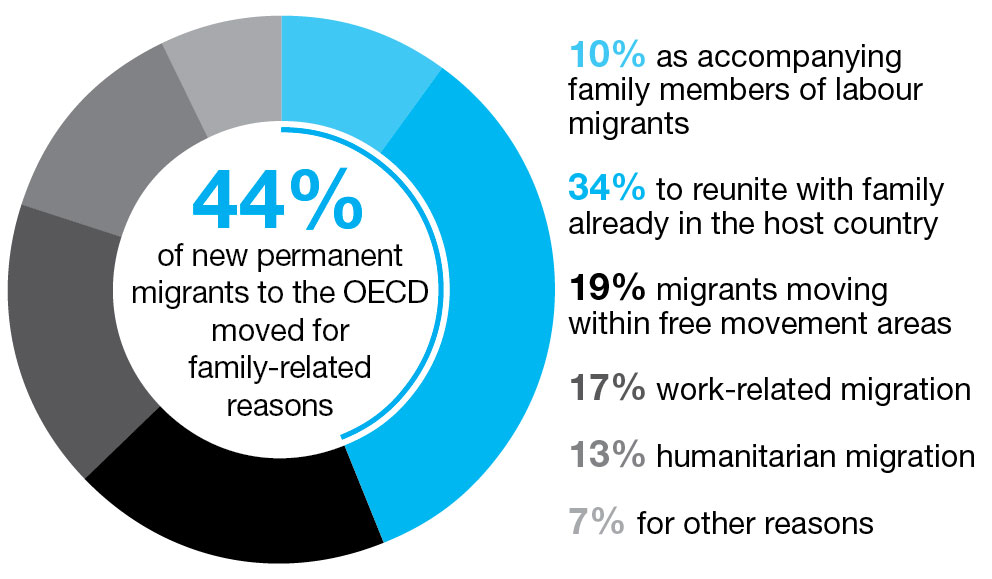

Public perceptions of migration can be warped by the extremes: overcrowded boats of refugees at one end of the spectrum and billionaires’ doomsday redoubts at the other. In most cases, however, people move for more prosaic reasons. “The number-one criterion is family reunification,” says Jean-Christophe Dumont, the head of the international migration division at the OECD’s Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs. “It accounts for 40 per cent of migration to OECD countries and about 70 per cent of regular migration to the US.”

The second-largest category of entry for migrants is work. As the demands of the labour market have changed, so has the profile of people who relocate for a job. With advanced economies increasingly requiring a skilled workforce, the level of education among migrants has risen. “About a third of migrants to OECD countries now have tertiary education,” says Dumont. “This reflects rising levels of education worldwide but also the fact that migration is costly. People who have the skills and means to make the move tend to be better educated.”

A corollary has been women making up a higher share of those moving countries than ever. “In the 1970s and 1980s, labour migration was mostly about supplementing the workforce in industrial sectors, such as the automobile and metal industries, which mostly employed men,” says Dumont. “Now the demand is greater in industries where women are more prevalent, such as the healthcare and service sectors. We are also finding that tertiary-educated women from low-income countries are using migration to improve their prospects, which might be limited at home.” In some countries with selective systems, the share of those with tertiary education is higher in migrants than among the native population.

Decisions over whether or not to move for work are often more complex than a matter of simply chasing the highest salary. “It’s not so much the wage that makes the difference but the longer-term opportunities for career development,” says Dumont. “If I’m thinking of migrating for work, the prospects for my children in the new country are also important.”

Remote working – an insignificant blip

A new type of labour-related migration is also becoming increasingly common: people working remotely in one country for companies or clients based in another. Until recently, working remotely on a permanent or semi-permanent basis was mainly the preserve of self-styled “digital nomads”, a subculture dominated by those in the technology sector. The coronavirus pandemic changed this, causing the rapid expansion of out-of-office working across white-collar industries. Many are taking advantage of their new geographic freedom to move to a different country without losing their jobs.

This has created a new set of challenges for immigration policymakers. “Some countries are simply clarifying rules around tourist visas to make it clear whether visitors are able to work remotely,” says Kate Hooper, a senior analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank. “Others have introduced dedicated digital-nomad visas but these tend to be more of a marketing tool and uptake has been low. Most people still choose to simply work while on a tourist visa. It’s easier, quicker and often cheaper.”

Portugal rolled out a highly publicised bespoke digital-nomad visa in 2022 and Spain followed suit in 2023. These schemes, however, have not made a particularly noticeable difference: the Iberian nations have been issuing about 20,000 digital-nomad visas a year, compared to about 1.5 million other kinds of tourist and short-stay visas.

Hooper says that the growth of remote working has resulted in migration-related policy issues that go far beyond visa definitions. “Where will people be taxed – are they establishing a legal presence in another country?” she asks. “If you’re signing contracts in a new country, are you exposing your company to local labour and employment laws? How portable are pensions? Remote work is the future but there are different systems that need to be updated to keep up with that trend. A lot of employers are shy about exposing themselves to risks in these grey areas.”

How migration protects wealth

High-net-worth individuals (HNWIS) face yet further considerations when it comes to migration. The main issue is whether they should live in the same place as their money. “Our industry is called investment migration but most of our clients don’t physically relocate,” says Dominic Volek, the group head of private clients at consultancy Henley & Partners. Nonetheless, more and more HNWIS are seeking to cultivate a strategic presence in various far-flung locations.

“We talk about ‘geopolitical arbitrage’: it’s about hedging against risks at home while capitalising on opportunities offered by other countries,” says Volek. “An American family we work with might attain residence in Costa Rica, citizenship in Europe, a Caribbean passport, a UAE Golden Visa and permanent residence in New Zealand. All of this means that they’re properly hedged against who knows what might happen in all of these jurisdictions. Since the Russia-Ukraine war, we’ve even been having discussions with families in Europe about conscription. We launched a citizenship programme in Nauru last year. The first family we worked with who received a Nauru passport was German. And why would these people want citizenship of a tiny South Pacific island without moving there? To avoid their child getting pulled into a war.”

Ten countries that want you

Looking to start afresh somewhere new? Many nations are offering work visas to those with specific skills.

1.

Fishmongers

Sweden

It might have many lakes and a vast Baltic coastline but Sweden is lacking fishmongers. A 2023 government report into at-risk sectors suggests that knowing your way around a rainbow trout could now gain you a work permit.

2.

Musicians

Germany

Germany’s artist visa allows musicians, including DJs, to apply for long-term residency. The only requirements are that the applicant must be based in Berlin, can provide a detailed CV and has a clear financial plan for the years ahead.

3.

Ambulance drivers

Denmark

Denmark’s immigration policies received much attention last year for limiting inward numbers. The country’s latest list for in-demand skilled workers features 57 professions, including ambulance driver.

4.

Film-makers

Japan

Japan offers a special visa for film-makers, painters and poets to work in the country for between six months and three years. But any aspiring Kurosawas should know that competition is fierce – only about 300 applicants are accepted each year.

5.

Chimney sweeps

Austria

In Vienna, every home’s chimney must be inspected by a Rauchfangkehrer once a year. These chimney sweeps’ responsibilities extend to assessing boilers and hot-water tanks. Any skilled German-speaking sweep can apply for a work visa.

6.

Arborists

Australia

According to the Australian government’s most recent review of labour shortages, the nation is lacking skilled arborists. Tweaks to the country’s relatively restrictive immigration laws mean that employers can now use the “skills in demand” visa to hire much-needed tree experts.

7.

Architects

Vietnam

A new Vietnamese state decree has made hiring foreign engineers and architects a priority. The new talent visa affords architects special entry, along with investors, university researchers and public sports figures. It comes as the country embarks on several large infrastructure projects.

8.

Bakers

Canada

Bakers looking for more dough should consider heading to Canada. The country has launched an international campaign to attract bread makers, confectioners and pastry chefs. Provinces that are in particular need include Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta. Time to lay down some flour.

9.

Thai chefs

New Zealand

Thai cuisine is now global – and one country that can’t get enough of massaman curry is New Zealand, where the government has set up a special visa just for chefs migrating from Thailand. Once their application has been approved, they are welcome to stay for four years. Grub’s up.

10.

Radiographers

South Africa

South Africa has suffered an acute brain drain of medical professionals, many of whom emigrate to the UK. The inclusion of radiographers on the country’s list of critically understaffed jobs means that any qualified applicant will gain 100 points towards their SA General Work Visa.

Read next: How holding multiple passports is shaping a new global citizenship reality