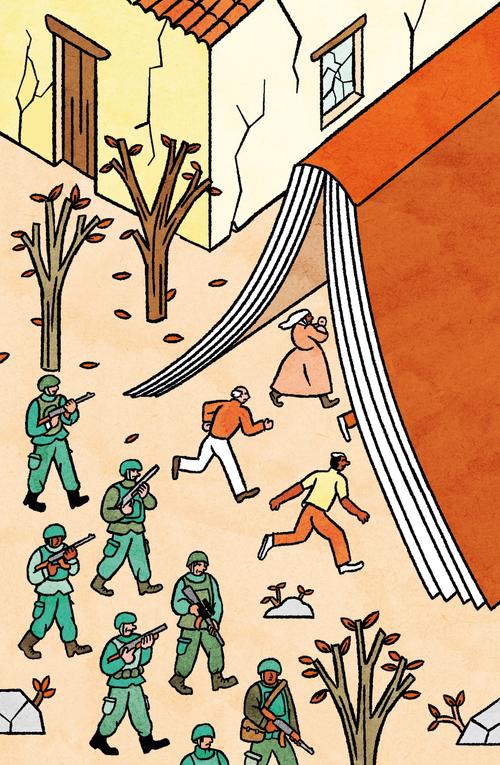

Poetry is a way that people survive the fear and uncertainty that war brings

We can be overwhelmed by reports filed from conflict zones. While they give a comprehensive account of a situation on the ground, sometimes the language fails. Which is where poetry comes in.

One Saturday last October, as we entered an elegant restaurant in downtown Beirut for lunch, my Lebanese colleague pointed out a Hezbollah minister sitting smoking shisha. He was a slim man in his early fifties, wearing a grey baseball cap and, like the other three men at the table with him, black jeans and a black T-shirt. We stopped to talk; Israel’s war against Hezbollah was at its height, with daily bombings of targets across the country. After we got to our table we laughed, slightly nervously, about whether the Israeli drone whirring overhead would drop its bomb before or after we had eaten our main course.

Black humour is a staple of life in places such as Lebanon, where your destiny seems to be beyond your control. The same Lebanese colleague had been late that morning because she was stuck in a traffic jam; the Israelis had bombed a car on the road ahead, killing two people inside. I never did find out who. A Hezbollah commander and his wife? A visiting Iranian financier? It could have been either. You couldn’t know whether the person in the car you were passing, or in the house next door, or on the street as you walked by, might be a target.

Poetry is another way that people survive the fear and uncertainty that war brings. Four lines by Bertolt Brecht have become an aphorism:

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.

After living through the civil war in the 1970s and 1980s, four Israeli invasions, numerous assassinations of leaders, economic collapse and, in 2020, an accidental explosion of nitrates at the Beirut port, which has been described as the most powerful non-nuclear explosion in history, Lebanese people are fed up with being praised for their resilience. A poem by the New Orleans poet Zandashé l’Orelia Brown that starts, “I dream of never being called resilient again in my life/I’m exhausted by strength”, has been circulating on social media. It resonates across borders and cultures.

People often turn to poetry in times of personal grief and trauma, as well as political crisis. This is why, in my career as a reporter often covering conflict, I have always carried a volume of poetry with me. Poetry has an allusive power that journalism lacks; it picks up where we leave off. I turn to it when my own words run out.

Though the TV images we see daily have a huge effect, journalistic language sometimes fails to convey the intensity of the experience. As journalists we pride ourselves on the clarity of our prose and on making complex stories simple. Our job is to explain why terrible things are happening and to challenge the euphemisms used by politicians and military spokespeople. We also try to convey the thoughts and feelings of those we meet and a sense of what it feels like to be on the ground. Yet we may lose the deeper meaning, such as the universal significance of what we have witnessed or the contradictory emotions that war engenders.

On 21 October, Israel bombed, without warning, a building next to the Rafik Hariri hospital, the biggest health facility in Lebanon. Eighteen people were killed. We arrived the following morning to see a bulldozer scraping away at the wreckage. It would stop and the watching crowd would fall silent so that people could listen in case any mobile phones were ringing from inside the mountain of rubble. A man in a red baseball cap with tattooed arms scrambled up and started desperately digging with his bare hands. He was looking for his five-year-old son, Ali. Reaching into the crumbled ruins of his house, Ali’s father pulled out a multicoloured sack. He turned it upside down and a stream of plastic toys poured out, their bright pink, yellow, red and blue stark against the grey ruined concrete. “Are these the Hezbollah weapons?” he shouted. I thought of Anna Akhmatova’s poem about the siege of Leningrad, in which she compares the sound of a bomber to thunder that doesn’t bring blessed rain:

My distraught perception refused

to believe it, because of the insane

suddenness with which it sounded, swelled and hit,

and how casually it came

to murder my child

The shock of the last line echoed the shock I felt in the moment, watching the unspeakable pain of a father who has lost his own.

The dominance of the Great War soldier-poets – Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg – in Western culture might lead to the assumption that war poetry is a male preserve, and that Western poets have a monopoly on the form. This is far from the case. The first known war poet was a Sumerian high priestess, Enheduanna, who lived in Ur, in what is now southern Iraq, in about 2,300bce. Contemporary poetry, much of it written by women, reflects the fact that modern conflicts tend to kill more civilians than soldiers. The late Irish musician Frank Harte said, “Those in power write the history; those who suffer write the songs.” A lot of songs and poems have been written in recent years.

Across the Arab world, poets are revered. Poetry is not seen as an elite pastime but central to culture and identity. Poets may be as important as soldiers in other conflicts too. A statue of Taras Shevchenko, with his massive, drooping moustache, stands in nearly every town I have visited in Ukraine. The reputation of the national poet, who wrote revolutionary verse in the 19th century, has been further elevated by the 2022 Russian invasion. In Borodyanka, a small town near the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, which saw some of the worst of the early fighting, he surveys a bombed-out apartment block, the windows blackened and broken.

More than 150 years on, his struggle is not yet won. A new generation of Ukrainian poets has been born of the war, writing in Ukrainian not Russian, part of an assertion of Ukrainian culture. Focusing on physical suffering, Western journalists may fail to see the importance of art to people struggling to preserve their humanity. Mental health and trauma are a focus but we are often oblivious to spiritual and religious needs, and to the yearning for the comfort of ritual and recitation that poetry provides.

That yearning is increased when people are forced to flee. Refugees bring only what they can carry, which often means songs, stories, poems and prayers that they know by heart. They can’t go back, not just because it’s dangerous but because the country they grew up in no longer exists – war changes everything. They are lost in both space and time. Verses learnt on a grandmother’s knee or in school are anchors to the old life and provide a source of strength and identity that give solace in an alien and often hostile world. In TS Eliot’s words from “The Waste Land”: “these fragments I have shored against my ruins”.

While we ate our lunch in Beirut, the minister’s driver leant against his black four-wheel-drive with its tinted windows, smoking and looking up at the drone, before finishing and whisking his boss away. A few minutes later a new party arrived at the table. They couldn’t have been more different: four fashionably dressed women with bee-stung Botox lips and sunglasses perched on their head. The two divergent sets of table guests are part of the complexity of contemporary Lebanon, land of chuddars and bikinis, political parties with their own militia, and multiple sects and religions. Even in the darkest of times, it’s possible to admire the glory of Lebanon’s contradictions and diversity.

As the great Lebanese-American poet Khalil Gibran wrote in the 1920s:

You have your Lebanon and its dilemma

I have my Lebanon and its beauty

Your Lebanon is an area for men from the West and men from the East

My Lebanon is a flock of birds fluttering in the early morning as shepherds lead their sheep into the meadow and rising in the evening as farmers return from their fields and vineyards

You have your Lebanon and its people

I have my Lebanon and its people

Poets don’t have the answers but they can turn the horror of war into works of beauty. Journalism is of the moment; poetry lasts forever.

About the writer:

Hilsum is international editor at Channel 4 News in the UK. Her new book, I Brought the War with Me: Stories and Poems from the Front Line, is published by Chatto & Windus.