On the outskirts of Jakarta, at the factory of Indonesia’s largest cosmetics company, thousands of staff in mint-blue uniforms are working around the clock to keep production running. For Paragon Corp, which owns 14 beauty brands and 43 distribution centres across the country, business is booming. Flagship lines such as skincare and cosmetics label Wardah (“rose” in Arabic) have already surpassed brands from multinational corporations such as Unilever and L’Oréal in popularity to become top performers in Southeast Asia. The family-owned business has achieved triple-digit growth for labels including Wardah by operating on its own terms: hiring the best talent and empowering them to pitch ideas; getting creative with livestream shopping; and offering a more universal perspective on halal beauty, which appeals to Indonesia’s Muslim-majority population and the region’s beauty connoisseurs. As well as abiding by strict certification standards (products are free of ingredients derived from alcohol and pork), Paragon also invests in sustainable sourcing and cruelty-free testing.

The group’s success is reflective of the explosive growth of the country’s broader beauty and skincare sectors, which generated about $7.4bn (€6.5bn) in revenue in 2024. Paragon accounts for 25 per cent of the market; that equates to enormous volumes of brightening cream, compact powder and cosmic lash-volume mascara. Last year customers bought about 30 million facial cleansers by Wardah and lip creams by Oh My Glam, another make-up label under the Paragon umbrella. There’s also plenty of room for further growth. Sunscreen is flying off the shelves but only 25 per cent of Indonesia’s 282 million people currently use it.

Paragon makes up to six million items a week and about 2,000 types of products. At its factory compound in the Banten province, production is split by category: powders in one building, lipsticks and other semi-solids in another. During Monocle’s visit to “liquids and creams”, khaki bottles of facewash are coming off the production line. The clean branding belongs to Kahf, Indonesia’s top male grooming brand. The label’s rapid growth (it launched in 2020) is emblematic of Paragon’s successful formula: employ the right people and empower them to innovate.

Two product developers in their twenties, Reza Sukamto and Billy Dharmawan, came up with Kahf (“cave” in Arabic) while completing their management-trainee programmes. They proposed a brand for Muslim men that could emulate the success of Wardah’s halal beauty range for women. When management approved the idea, the duo got to work, seeking to understand their target market. “There are all kinds of stereotypes about Muslim men but by spending time in the community we realised how wrong they are,” says Sukamto, a microbiology graduate. “Muslim men are actually progressive and open to discussing new things, such as inclusivity and social impact. Their spending is high and they have high standards for the products they use.”

The black-bottled eau de toilette Revered Oud was Kahf’s first big hit. Since then, its body washes, deodorants, sunsticks, hair pomade and beard serums have found success among Indonesian men irrespective of religion. Apparel is next. “We want to become a one-stop solution for all men,” adds Sukamto.

Paragon Corp turns 40 this year. It was founded in 1985 by Nurhayati Subakat, who quit her quality-control job at the German haircare company Wella to launch her own professional haircare product. The line quickly became popular among Jakarta’s salons and her three children now run the family-owned company. They all had to chip in.“Production took place on the second floor of our house and, as children, we had to help pack the bottles in the boxes and take telephone orders,” says Sari Chairunnisa, the youngest of the Subakat siblings and the company’s deputy CEO and head of research and development. She joined her mother’s company in 2014 after completing her studies as a doctor and dermatologist.

Paragon’s annual revenues are roughly 400 times bigger today than at the start of this century. The turning point came between 2008 and 2010 when a Hijrah movement – a journey of self-improvement to become more devoted – kicked off in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country. More and more women opted to wear a hijab as an expression of their Islamic values and Wardah’s halal certifications and campaigns, featuring models wearing headscarves, suddenly struck a chord.

“That lifestyle and that behaviour weren’t being represented by Maybelline or Revlon,” says Chairunnisa, who wears a headscarf and has experienced at first hand how hijabs went from holding back careers to opening doors. Modesty and make-up might sound like a paradox but not to Chairunnisa, who pulls off both. Simple looks that achieve a clear, blemish-free complexion are big money here.

Opinions vary on what triggered the Hijrah movement. Chairunnisa points to the end of Suharto’s oppressive 30-year dictatorship in 1998. “We have since been able to express our identities as Muslims or Chinese and not only as Indonesians,” she says.True or not, Indonesia’s conservative shift is continuing – and might have huge implications. From next year, all beauty and cosmetics on sale in Indonesia must be certified halal, posing a challenge for Chinese and Western competitors, which will either need to abide by the new certification standards or place warning stickers on their products, informing customers that they are not compliant. The legislation was introduced more than a decade ago but companies were given time to comply. While this might seem like a big win for Paragon, for Chairunnisa it’s “business as usual”. The company has never used halal as its unique selling point and cannot claim exclusivity.

The hard work was done in the 1990s and early 2000s, when Paragon’s procurement team travelled the world to educate suppliers of raw materials, such as glycerin and vitamin D, about halal certification. “Now 95 per cent of our raw materials are being imported from France, the US, Japan, South Korea and China,” says Chairunnisa. “We told these suppliers that halal is for the Indonesian consumer, not for Paragon, so try to imagine the number of cosmetic companies in Indonesia and how much they will buy from you.”

The focus at Paragon is broadening the concept of halal beauty to resonate with international audiences regardless of religion. New halal brands are also committing to ethical testing and catering to a wide range of skin tones. For example, professional make-up brand Makeover has become a big hit with non-Muslim consumers, largely thanks to its flagship cushion blusher, which comes in 24 shades – beating every other brand in the market. “Right now, halal beauty is still very much rooted in religion but, for me, it’s about creating good products – a very global concept,” says Subakat, explaining that there’s plenty of potential for growth in international, non-Muslim markets.

It’s partly why Paragon opened new headquarters in February: a modern, open-plan space in South Jakarta reflective of the business’s global ambitions. About 14,000 people (referred to as Paragonians internally) work here, while the three Subakat siblings float around the firm’s Jakarta and Banten properties.This agility and flat hierarchy has given Paragon the edge over the multinational corporations that have been slower to react to the market. But there is no letting up.

Competition is getting tougher, with a wave of new entrants, both local and international, attempting to enter the world’s fourth-most-populous country. Chinese skincare brands, such as Skintific, have aggressively entered Southeast Asia this decade. Their arrival coincided with the coronavirus pandemic but both disruptions ended up being a “blessing in disguise” for Paragon. They forced the company to unlearn its old ways and begin innovating across departments, from product development and design to sales and marketing. “We see it as a calling to improve ourselves,” says Chairunnisa, who is more curious than fearful about China’s envelope-pushing approach to e-commerce. Harman Subakat, the ceo, also waves away any concerns – the market is too undersaturated for him to have to worry. The country’s young population is still growing, so there’s plenty of skin in the game. “Do you know how many Indonesian men use deodorant?” Subakat says. “About 30 per cent.”

In answer to the competition, Paragon began livestream shopping in 2023 and unveiled a purpose-built filming studio last year. Inside the low-rise, warehouse-style building near the head office, sales staff sell products on four e-commerce platforms: TikTok, Shoppee, Lazada and Tokopedia. A typical eight-hour shift includes two hours of livestreaming, two hours’ rest, two more hours of selling and then two hours of content creation. There’s always someone on-screen and midnight is one of the peak times for selling. “Every minute matters,” says our guide, Evelyn, who shows Monocle the different studios. Every host sits in front of several cameras and lights. There’s a green or purple screen behind them and a table full of products at their fingertips. By the end of a shift, faces and arms are covered in different shades of red and brown.

Many of the hosts are former flight attendants and each is matched with a specific brand. Those with a “Wardah face” – clean, calm and kind – push the flagship product and tend to wear a hijab. Labore hosts don white coats and conduct interviews with dermatologists, whereas pink is the wardrobe colour for Instaperfect, a “Halal glam” brand that grew out of Wardah. Yuui is Makeover’s star host. She was recruited from an offline shop, which remains Paragon’s main sales channel. Dressed all in black, she speaks and smiles non-stop, periodically ding-dinging a metal bell to announce a promotion.

As the sun sets over Jakarta and observant Muslims across the capital await the evening call to prayer, Monocle asks Harman Subakat about Paragon’s future. Go public? Enter the Middle East? Achieve an annual turnover of $2bn? Subakat remains tight-lipped and insists that there isn’t a big revenue goal to hit or a global roll-out plan. Individual teams are not even given targets – the focus remains on social impact, healthy growth and empowering employees. “Having a good dream and taking good action” is how Subakat summarises the company’s ethos. Foreign investors would be tearing their hair out at this point but Paragon is an Indonesian family business with its own tried-and-tested formula for success.

Indonesian beauty brands to watch

Oaken Lab

Husband-and-wife duo Chris Kerrigan and Cynthia Wirjono launched the perfume brand Oaken Lab in 2018 as a salve for mass- market deodorants and skin-tingling aftershaves. The Jakarta perfumer now has three shops in Indonesia and is stocked by top hotels, including 25 Hours in Jakarta and Potato Head in Bali.

Hale Skincare

Established in 2019, Hale thrives on simplicity, with clean graphic design, fragrance- and alcohol- free ingredients and competitive price points. Its co-founder, Bellinda Putri, had severe skin problems as a teenager and was inspired by her experiences of using Australian skincare while at university to create an affordable skincare line for Indonesia.

Kusuma Kosmetika

Founded by Tiara Budiendra, this new make-up brand embraces Indonesian heritage, starting with a deliberate decision to forgo the industry trend for English brand names. Kusuma Kosmetika’s vegan products cater to the skin tones of the people who populate

the vast archipelago, favouring darker shades over the whitening products popularised by the Korean beauty wave.

Like many luxury fashion houses, Antwerp-based label Dries Van Noten has been surfing the waves of change. Its founder, who bears the same name, has stepped down from the role of creative director and all day-to-day design responsibilities at the label he founded in 1986. The transition, though, couldn’t have been smoother.

Julian Klausner, a 33-year-old designer who has worked under Van Noten since 2018, has taken on the mantle. His debut show, presented at the Opéra Garnier during the last edition of Paris Fashion Week, was celebrated by the fashion industry for paying homage to the founder’s signatures while moving his vision forward. Meanwhile, Van Noten – who now sits on the front rows of his own shows to support his successor – has unlocked more time to tend to his garden in Lier, on the outskirts of Antwerp; oversee his label’s growing beauty line (most of which is heavily inspired by the aromas of his famous garden); and collect artworks, furniture and design objects from around the world for the brand’s newly opened boutique in London.

Visiting a Dries Van Noten shop has always been considered a creative pilgrimage of sorts: the brand’s Antwerp flagship and its Paris outpost on the Quai Malaquais are spaces where you can discover new artists, experience architectural landmarks or simply be inspired by taking in the colour palettes on the walls. In the Los Angeles store, there’s even a pianist greeting you at the entrance. “It really started in Paris in 2007,” says Van Noten. “That was the first time we approached a store as something more than just a place to show clothes. Everything from the garments, the furniture and the art [has to] work together.”

With backing by Puig, the Spanish group that bought the brand in 2018, Van Noten now has an opportunity to apply his vision for retail to new cities – and he has been doing so mindfully, taking his time and ensuring that each location has its own story to tell. In London, he picked a former bank on Hanover Square with barely visible signage and no other luxury shops in sight. “The space began to guide us – once we started placing objects, choosing textures and letting in the light, it started to show us what it needed,” says Van Noten. Contrast was one of the needs he quickly identified, choosing to juxtapose the Grade II listed building’s historic features with modern design items. “There’s a certain calmness and contrast that I associate with Flemish aesthetics and that comes through in the store too.”

Centre stage is a sculptural, brass chandelier by Belgium-based Vladimir Slavov, a one-of-a-kind design that Van Noten spotted at the Objects with Narratives gallery in Brussels. “This wasn’t a custom order but I found a way to postpone another client’s project to do this for Dries,” says Slavov from his workshop in Zaventem, just outside Brussels, where he sketches and creates prototypes and casts all his objects. A design purist, Slavov speaks of his love of “minimalist, strong shapes that can stand on their own” when it comes to design and to fashion. “The few [clothing] items I own that do attract a bit of attention are from Dries,” he adds with a smile, referring to an embroidered wool bomber jacket by the brand. “I don’t dress in a fashion-orientated way but Dries Van Noten designs appeal to me in a way that surprises even myself.”

As well as highlighting the works of fellow Belgian-based artists, Van Noten also makes a point to celebrate local makers. Another significant commission in his new London shop includes a round Convex mirror designed by Collier Webb and crafted at its workshop in Sussex. “Dries just walked into our showroom on Pimlico Road,” says David Arratoon, design director at Collier Webb. “I’m not sure if he was intending to come in or was just looking around. He fell in love with one of the mirrors and it all started from there,” adds Arratoon, who then worked on creating a custom mirror for the shop, as well as a brass-and-glass lighting fixture. “There was an ongoing discussion about the antiquing and patinating process of the mirror, which is done by hand and can be adapted to change the depth of the colours and overall feel of the object. We want our designs to feel like they’ve always been there.”

In fact, the entire boutique appears to have always been there. There might be something new to discover in every corner – menswear, womenwear and beauty ranges; Van Noten’s record collection; and artworks by the likes of Tracey Emin and David Hockney – yet the personal stories and emotions behind each object come together to create a welcoming, lived-in space. “You might see something very minimal next to something ornate, or something industrial beside something soft. It’s about finding harmony in this kind of tension,” says Van Noten.

driesvannoten.com

Stylist: Kyoko Tamoto

Hair & make-up: Milla De Wet

Model: Kilean Isaak

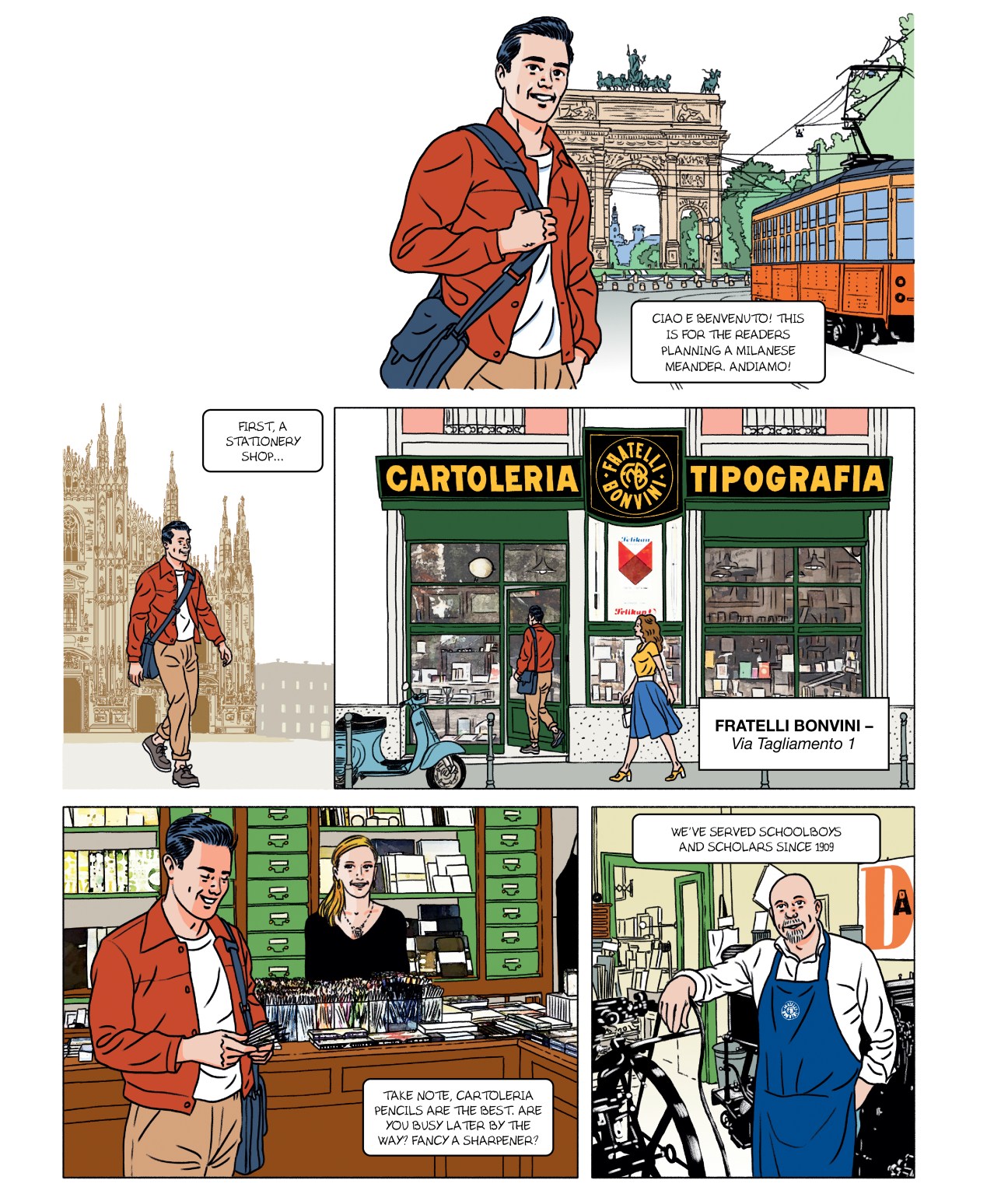

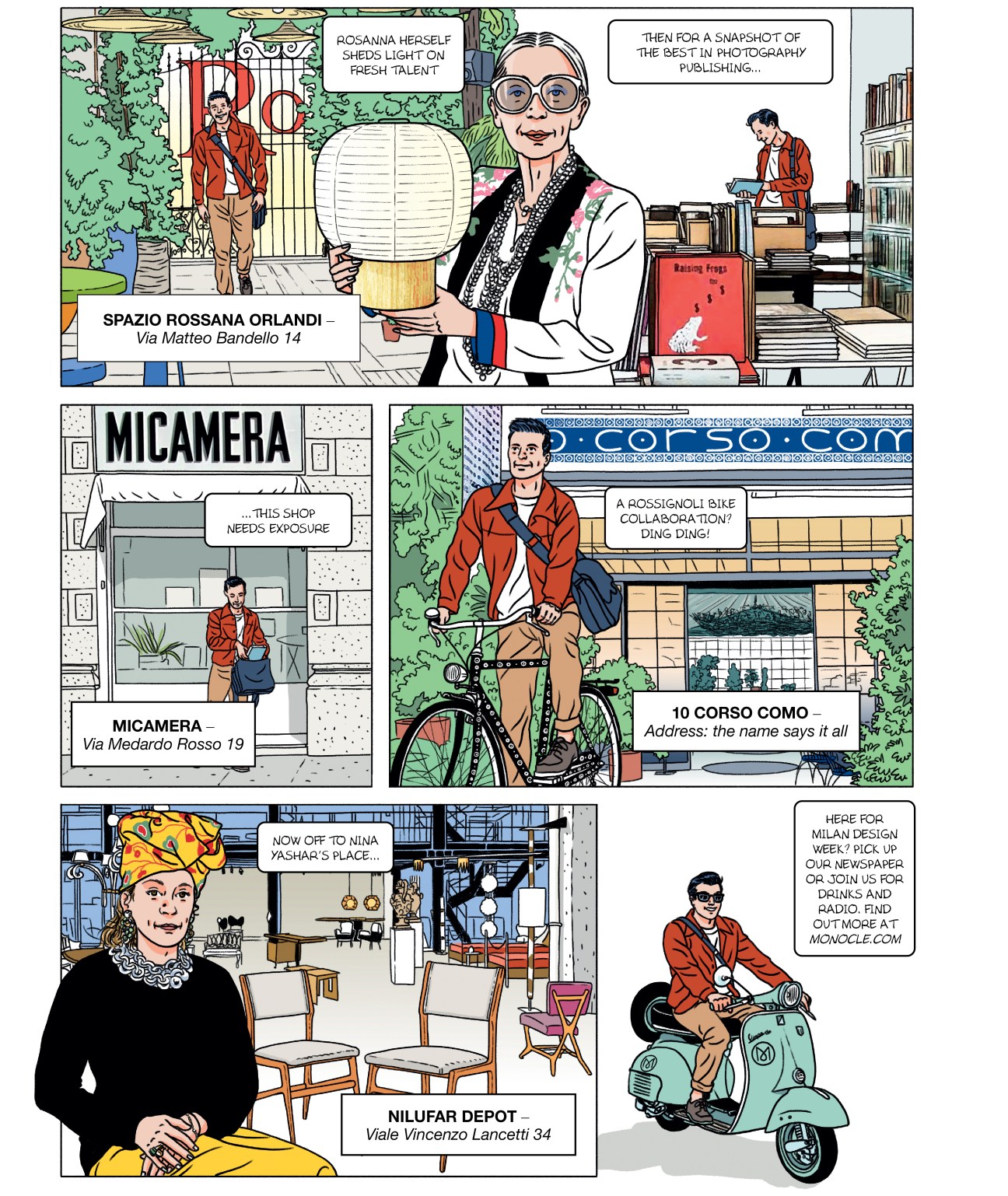

1.

Oobatz

Paris

Dan Pearson moved to Paris to study international relations but found that there were other ways to win hearts and minds. The chef first made mouths water with a pizza pop-up at the Michelin-starred La Rigmarole. Now he’s back with Oobatz in the 11th arrondissement. The line-up features six pizzas, each made with market-fresh ingredients before its 90 seconds in the Swedish pizza oven at 480C. Monocle’s favourite has a marinara base, with pork and veal polpette and creamy caciocavallo. Call ahead as tables are tough to snag.

2.

Dodeka Piata

Athens

True to its name, Dodeka Piata (“12 plates”) offers a dozen dishes in celebration of the Greek concept of mezedes (sharing plates). The new restaurant in Koukaki is overseen by chef Pavlos Kyriakis and features mosaic-tiled floors and white linen tablecloths, with wooden chairs replacing the straw seats of a taverna. The menu is modest in volume but the smoked tzatziki and tyrokafteri, a spicy whipped cheese dip, will leave you satisfied. The pork gyros with paprika and onion are exceptional.

36 Odissea Androutsou, Athens 117 41

3.

Uno di Questi Giorni

Bologna

This restaurant from the duo behind Bologna’s much-loved Ahimè has been four years in the making. Whenever co-founders Lorenzo Vecchia and Gian Bucci were asked about the opening date, they’d reply “Uno di questi giorni” (“One of these days”); the name stuck. Designed by Trieste-based studio Metroarea, the interiors feature exposed wooden beams, contemporary lighting and cream-coloured sofas. But the real showpiece is the large open grill, where everything from Jerusalem artichokes to Po Delta oysters are cooked as part of the grill-only menu.

unodiquestigiorni.it

4.

Esra

Amsterdam

You’ll find this 26-cover Turkish offering in Amsterdam’s formerly industrial eastern docklands. Its appeal lies in the ever-changing menu of its London-born Turkish Cypriot owner, Selin Kiazim (pictured, on right, with co-owner Steph De Goeijen). “The food scene in Amsterdam is always evolving,” she says. “Esra’s menu switches with the seasons, sometimes even after a day.” Past menus have featured pollock with pistachio cream, and herring roe and Turkish eriste egg noodles with pickled maitake mushrooms and sheep’s cheese sauce. The wine list features appellations from Georgia, Croatia and Greece.

esra.amsterdam

5.

Bar Super

Barcelona

Bar Brutal and its bottle shop Can Cisa brought Barcelona’s most enterprising drinkers round to biodynamic wine when it opened in 2013. Its new sibling, Bar Super, is located next to the Mercat de Santa Caterina in El Born. Given its prime location, twin restaurateurs Max and Stefano Colombo, as well as winemaker Joan Ramon Escoda rely on cuina de mercat (market produce), to which they add the Venetian sensibilities that they channelled into their debut opening, Xemei, an Italian osteria in Poble Sec. At Bar Super, expect fresh prawns, succulent tuna carpaccio and colourful varieties of beetroot. The wine list features Catalan appellations from winemaker friends, as well as an in-house bitter made in collaboration with Genoese bodega La Ricolla.

barsuper.com

6.

Ghost

Bali

Ghost Kitchen and Record Bar mixes wood-fired cooking with a warm vinyl soundtrack. Executive chef Tim Stapleforth blends Balinese flavours and fresh produce with what he grew up eating in Queensland. Standouts include the babi guling crumpet, a play on the Balinese hog roast.

No 99 Jalan Pantai Berawa

Lanzarote is known as the “island of 1,000 volcanoes” and its dramatic landscapes are vivid reminders of nature’s power. “Don’t worry – only one of the volcanoes is considered active,” says longtime resident Adrián Nicolás von Boettinger, as he leads Monocle through Lagomar, an architectural marvel built into an old rock quarry. At first glance, Lagomar’s façade barely registers as part of a building. The semi-subterranean structure features rooms, tunnels and terraces; only the balconies, stairs and footbridges, which cut into the rock surface, offer a sense of structure, while looking like beads of icing flowing down the side of an uneven cake.

Lagomar encapsulates how Lanzarote, the easternmost of the Canary Islands, has grabbed the design world’s attention since the 1960s with its idiosyncratic combination of oddity and invention. Its lava-hewn landscapes are arresting spectacles that can help to unlock architects’ imaginations; the inhospitable landscape, however, also prompts sobering civic discussions. The island has long been grappling with questions of how to live within its limitations and make the most of tourism without being overwhelmed.

With his sister, Tatyana, Von Boettinger took over the Lagomar property from their parents, architects from Germany and Uruguay, who bought the cliffside home in a state of disrepair in 1989. “There was so much mystique surrounding the building that they put down a deposit for it without even stepping inside,” says Tatyana, who adds that it was once home to Egyptian film star Omar Sharif.

After a gun-toting squatter was politely paid to leave the premises, the site underwent several years of structural improvements. In 1997 the house finally reopened as an architectural museum; more recently it was renovated as a restaurant, bar and music venue (plans for an artist’s residency are also in the works). It’s a microcosm of the island’s identity crisis: a vision for the future that’s firmly anchored to the past.

Lagomar is unique but in some ways it isn’t alone. Since the 1960s the island has walked a tourism tightrope in order to transform an agrarian society into a modern one, while trying to balance economic and ecological sustainability. From the 1960s to the late 1980s, artist and sculptor César Manrique was the island’s visionary-in-chief and, in effect, its architectural art director. Aghast by the postwar construction boom on neighbouring islands Tenerife and Gran Canaria, Manrique championed an ethos for Lanzarote that honoured the landscape, preserved tradition and resisted harmful development. He also designed scores of the traditionally inspired structures hewn into the island’s almost extra-terrestrial looking rocks.

Manrique’s less-is-more vision often sat uncomfortably with the island’s financial and political ambitions. The tourism sector, in particular, bridled at the idea of being constrained by an artist’s whims. Over the years, many hotels of varying standards were built and entire coastal towns turned into holiday resorts – much to the chagrin of Manrique, who agitated for restraint until his death in 1992.

To some, the artist and sculptor’s message was nuanced and prescient; to others, however, it was plain confusing. The house where he lived between 1968 and 1988, built into a petrified lava field, is now the base of his eponymous foundation. Among its exhibits is a video of Manrique warning about the island’s existential decay and criticising various beachfront hotels, mostly in front of the kind of visitors who stay in such places. It’s unclear whether his fervent approach was persuasive or just made those listening feel unwelcome.

“It’s not tourists that people are tired of,” says restaurateur Georgia Coles. “We love them and live off them. The problem is the tired model of tourism.” Today is the soft-opening of her new venture, La Lapa, and the first-day fluster is palpable. Coles steadies the ship, keeping an eye on the hungry guests in the dining room, while telling Monocle about some of the local tensions in the front bar. “In summer the taps in some of Lanzarote’s towns run dry but then we see hotels’ water supply safeguarded,” she says. “Residents can feel like their concerns are secondary.”

This delicate balance – between local and visitors’ interests, between too many tourists and too few – is on everyone’s lips. “Lanzarote teaches you how to live with very little,” says Zoe Barceló, an art director from Alicante who started a new life here with his partner, Geo Giner, a fashion designer from Barcelona. They tell us about their previous work lives, in which demanding deadlines meant more than 10 hours of screen time a day. “This is sort of a pre-retirement,” says Giner with a grin, gesturing at his surroundings. Looking for a rental property, the couple found a run-down toolshed and perrera (a house for hunting dogs). They have transformed both into an impressively appointed modern home and studio.

“We have seen more people coming to the island looking for peace, sometimes silence,” says Giner. But life didn’t stay quiet for long for the pair, whose new landscape-inspired clothing brand, Latitud Fuego, taps into the surf culture that’s thriving in coastal towns such as Caleta de Famara. Selling pieces sourced mainly from Portugal but embroidered by a Lanzarote-based artist, they started with 200 garments, which quickly sold out. The couple also juggle consulting work with other small businesses, helping to upgrade menus, signage and merchandise. “Manrique remains an inspiration,” says Barceló. “His legacy gives the island a conscience.”

For those working Lanzarote’s crater-strewn land, Manrique-style ideas of minimal intervention are more than just theoretical, given how difficult it is to cultivate crops here. Self-taught winemakers Eamon López O’Rourke and Laura Fábregas Camacho are the married couple behind a winery called Cohombrillo. The 13-hectare site hosts bi-weekly tastings in a garage. “Our techniques help us to make do with very little,” says O’Rourke. “We try to stay attuned to the limitations and wisdom of the land. Lately, we have been getting a lot of visitors from Japan who are curious about how we cultivate the volcanic soil.” He points to a pallet loaded with 300 bottles earmarked for export to Asia, underlining what that means for business.

María José Alcántara Palop is the director of MIAC, a fort turned-modern art museum, as well as of Lanzarote’s biennale. The current edition, which runs until 30 June, features excursions around volcanoes that morph into panel discussions and performances staged inside “teleclubs” – rural bars known for bringing the first televisions to the island’s remote villages. “Lanzarote needs more artists and more spaces – to be more courageous and insistent, even in the face of resistance from a bureaucracy that’s stuck in its ways,” says Palop, who worked with Manrique when he was younger. “He taught us to be bold, to honour the island’s singularity. He envisioned Lanzarote as a beacon for creativity.”

Yves Drieghe and Bert Pieters swapped their 20 sq m rooftop garden in Belgium for a 20,000 sq m hillside farm near the town of Los Valles. They refurbished the farmhouse, transforming it into a residence for writers, painters and makers that they named Hektor. Guests are encouraged to adhere to the island’s logic. “Small is beautiful,” says Drieghe. “Nature and the locals require respect.” The farm has gradually also become a kind of animal shelter, with a donkey, a duck, two pigs, some sheep and Frits the dog wandering the grounds.

Older generations of residents have been welcoming of new arrivals, as long as they respect the island and its people. “In our case, we held up a mirror to the beauty of their community and what they did so well,” says Drieghe, pointing to farming practices that harness the soil’s mineral richness despite the paucity of rainfall. “Meanwhile, artists bring with them new visions about what the island is and what it could be.”

Prior to this, Drieghe and Pieters ran an agency overseeing big projects, a small magazine shop and a café. “It’s no wonder we were stressed,” says Pieters, laughing. They apply their new stripped down life philosophy to the artists staying in Hektor, who don’t have to submit works at the end of their residency. “We have removed all of the pressure,” says Drieghe. “The same goes for us: there’s no intention to expand.”

Lanzarote address book

Stay

The Martínez family turned the estate of César Manrique’s grandfather into the 20-key César Lanzarote hotel, operated by the Annua Signature group. There’s also Casa de Las Flores, Palacio ICO and Buenavista Lanzarote. Serviced residences such as Villa Tenor offer more privacy.

Eat

Kamez í was awarded the island’s first Michelin star. Its Basque founder and architect Koldo Agurren designed a row of sea-facing domed structures where guests can enjoy a drink before tucking into a dinner prepared by no fewer than 16 chefs. Other high-end restaurants, such as SeBe and La Tegala, have more of the playful flair that the Canaries are known for. La Lapa in Arrecife is a fresh take on a traditional seafood café. Further south, Bodega de Uga offers an excellent wine selection and satisfying meaty dishes.

Drink

Winemaker Cohombrillo’s tasting sessions offer more than just insights into wine and cheese: they also reveal aspects of the island’s character. Hand-picked grapes are carried down the mountain on foot. “I call our type of viticulture ‘heroic winemaking’, because it has an enhanced human touch,” says co-founder Laura Fábregas Camacho. Also visit micro-brewery and bar Cervezas Nao in Arrecife.

See

A tour of Manrique’s architectural masterpieces is essential. With architect Jesús Soto, he made fantasy a reality in standout works including Jameos Del Agua, Mirador del Río, the MIAC museum’s sea-facing restaurant and the Monumento al Campesino.

Getting your bearings

The easternmost of the Canary Islands, Lanzarote (population: 163,000) is 125km off the north coast of Africa and 1,000km south of Spain. Its capital, Arrecife, is in the south. The airport serves 84 European destinations. Taxis are fine for towns but the best way to see the island is by renting a car.

SS Daley

UK

British designer Steven Stokey-Daley is becoming one of the most promising new names in fashion due to his ability to marry wardrobe classics, including plenty of suiting, with novel, humorous designs such as intarsia knits featuring playful illustrations. Stokey-Daley has a flair for “reinvestigating” wardrobe archetypes, such as duffel and trench coats, while experimenting with traditional fabrics.

For spring, he debuted a womenswear range: an elegant line-up of checked suits, tailored Bermudas and beaded skirts, referencing British painter Gluck. “I’m having so much fun,” says Stokey-Daley. “It’s an exciting adventure and it feels as though there’s so much room to explore and develop new ideas.”

ssdaley.com

Bode

Paris

Bode is branching out of the US with an ambitious retail opening in Paris, a stone’s throw from the Palais-Royal. “France has played a significant role in Bode’s history and the search for a retail location in Paris started more than four years ago,” says founder Emily Adams Bode Aujla, who has built a reputation for her eclectic designs, made using upcycled fabrics.

Working with her husband Aaron Aujla, one of the men behind New York-based interior design studio Green River Project, Emily drew inspiration for the boutique from the story of a French hotelier known for his love of fly fishing. The aim was to marry French and US tropes in the shop, which features antiques sourced from both sides of the Atlantic; sofas upholstered in silk; and stained glass. On the rails are the brand’s striped pyjamas, bold knits and embroidered shirts, as well as some Paris exclusives, including ties and shirting crafted from century-old French fabrics.

bode.com

Sophie Bille Brahe

Denmark & USA

Copenhagen-based Sophie Bille Brahe is becoming a household name in the world of fine jewellery, having opened her first international outpost on New York’s Madison Avenue last year. “The history of the street made it feel like a natural home for my designs,” says Bille Brahe, who often takes inspiration from ancient Egyptian constellations and Venetian mythology. “The shop’s design is rooted in my heritage, blending Danish craftsmanship with understated luxury,” she says of the minimalist space and its Dinesen wooden floors, lace curtains, worktables by Danish artisan Poul Kjaerholm and Mats Theselius chairs that are a nod to Bille Brahe’s muse, Peggy Guggenheim. To mark the opening, the brand debuted Collier de Madison, a take on its Collier de Tennis Royal diamond necklace. “The Madison Avenue shop isn’t just about bringing Copenhagen to New York,” says Bille Brahe. “I wanted the space to welcome visitors by telling my story.”

sophiebillebrahe.com

Plan C

Italy

Carolina Castiglioni usually thinks about herself when designing her label’s biannual collections, so venturing into menswear didn’t come naturally. “It was a request, especially from Japan, where male customers kept coming in our boutiques to shop for themselves,” says Castiglioni, who realised that most of Plan C’s designs – slim tailoring, roomy cotton shirts, workwear-inspired parkas and denim jackets – could be translated for men. “There have always been menswear inspirations in my work, so we focused on unisex pieces that can be styled in different ways,” says the Milanese designer (pictured), who unveiled her first menswear range at last summer’s Pitti Uomo. Plan C’s successful formula from the get go has been high-quality wardrobe classics sprinkled with novelty and excitement via the right accessories. Come spring, you’ll find the label’s menswear designs at its standalone boutiques in Tokyo and Osaka, plus a handful of multibrand boutiques including Dallas’s Forty Five Ten.

plan-c.com

Sans Limite

Japan

Yusuke Monden started his menswear label Sans Limite in 2012 after cutting his teeth in shirt design and production at Comme des Garçons. His concept is simple: wardrobe classics made well. Starting with a tight edit of six shirts, he has since expanded to ready-to-wear and accessories collections. “We don’t try to sell items for a specific season or drastically change fabrics for each collection either,” says Monden. Monden is committed to “Made in Japan” quality. “We do the patterning and planning internally, and then work with domestic factories,” he says. “When it comes to one-off items, such as patchwork shirts, hand-knit sweaters, or even rugs, we work on them in the studio and then send them off to the factories for completion.” Sans Limite’s Tokyo flagship is on a busy shopping street by the railway tracks that, post-Second World War, was home to a black market for US goods. It’s a world away from the neighbourhoods usually favoured by fashion brands.

sans-limite.jp

Junyin Gibson is the brand and creative manager for UK menswear outfitters Drake’s. Unsurprisingly, he’s a great dresser. “I like to think of my style as practical, considered and reflective of my life; there’s a blend of Hong Kong, my birthplace, and British styles,” says Gibson, who is now based in London.

Gibson oversees collaborations for Drake’s, which include collections with celebrated London restaurant St John and Maine-based boat-shoe specialist Sebago, as well as the making of its lookbooks. Over a drink at Leo’s, his favourite east London spot, Gibson tells us about his sartorial choices and sources of inspiration.

When did you begin to develop an understanding of style?

When I moved to the UK [from Hong Kong] aged 17. Being able to don wax jackets and caps was an exciting change of scene. I became passionate about layering these styles and playing with more colours and textures than before. While I love traditional Eastern styles, Hong Kong is a financial city – and a hot one too – so there’s a limit to which fabrics you can wear.

Who influences what you wear?

First, Drake’s creative director, Michael Hill. The consistency of his styling is what inspired me to adopt more of a uniform and focus on timeless styles rather than reacting to what others wear. When we travel together, he makes sure that we put time aside for exploring – some of my best finds have come from scouring Koenji’s vintage markets in Tokyo. Elsewhere, films such as In the Mood for Love and actors including Tony Leung and Toshiro Mifune have all had an effect on me from early on.

Are there items that you consider to be must-haves?

JM Weston’s 180 loafer is my staple shoe. I never wear lace-up shoes like Oxfords, only loafers. I like the way a good pair of trousers falls above them and they truly make an outfit. You’re always on the move. How do you dress while travelling? You have to be logical and prioritise utility but that’s what some of the best design does. In that regard, a utility vest is perfect for the airport: it’s light, everything you need is on-hand and you can layer it over anything.

How do you weave Eastern styles into your wardrobe while representing such a British brand?

Drake’s travels all over the world and takes inspiration from Japan, the US and beyond. For my own wardrobe, I love to pick up Lee Kung Man’s Henley tees – even Bruce Lee wore them.

Should we all adopt a uniform of sorts?

It makes mornings easier. The majority of my wardrobe works together because I’m always collecting timeless styles and similar silhouettes. When you have a good base of neutrals that work well, you can then throw in pops of colour. I always recommend a jumper or scarf wrapped over the neck.

In Taiwan, breakfast can be a rushed affair. On the curb in front of a street-food vendor, you’ll see scooters hastily parked as their riders, helmets still fastened, queue beside smart office workers and uniformed students, waiting for their turn to order. Now and then, a retiree or an idle auntie claims a low plastic stool, savouring their choice with unhurried ease. But for many, breakfast is eaten on the go as they sweep through the city.

The Taiwanese breakfast shop is a product of the region’s postwar history: its origins lie with the steady flow of wheat that came as part of Cold War-era aid programmes from the US and also with the arrival of mainland Chinese refugees who knew precisely what to do with it. Until then, rice, not wheat, was the island’s staple stodge and the latter was a foreign commodity, largely unfamiliar to most. For breakfast, wheat flour was used to make long, deep-fried dough sticks, flaky flatbreads or pillowy buns. Sometimes the flatbreads were rolled up with spring onions and an egg to form a dan bing, a morning staple. The first breakfast shops in Taiwan were street stalls, stacked with layers of bamboo steamer baskets and bouquets of fried dough sticks. Eventually, bricks-and-mortar locations began to crop up, though many maintain a certain simplicity: they tend to be humble, utilitarian spaces where food is prepared on a single stainless-steel flat-top griddle facing the street.

“Dan bing is usually pan-fried but we deep-fry ours,” Cheng Hsu-Chong, the second-generation owner of the Chongqing Soy Milk and Fried Egg breakfast shop, tells Monocle. The 50 year-old institution on the edge of a traditional market has neither a front wall nor a door. Why deep fry? “It’s faster,” he says. “And it tastes better.”

The main action takes place at a vendor cart in front of the shop, where Cheng’s son is poised over a fryer. He drops a thin flatbread speckled with spring onions into the bubbling oil, then cracks an egg into the fryer. As the bread crisps and expands, he folds it around the egg, lifting it from the oil, before adding a diced pickled daikon radish. With a swift motion, he hands it over to the cashier, who finishes it with a few generous shakes of ground white pepper. The dan bing is paired with a hot cup of sweetened, freshly brewed soy milk, a popular drink at Taiwanese breakfast shops.

The precise origins of the dan bing, which is more like a light puff pastry than fried dough, remains as murky as the bubbling oil from which ours has just emerged. In Mandarin, dan means “egg” and bing means “flatbread”. It is thought to have originated in Taiwan as an extra-thin riff on the spring-onion pancake. Variations exist, some more crêpe-like than others.

“Many people use the batter method but we just roll it out from dough,” says Qin Hui Lin, the owner of Miss Qin’s Soy Milk Shop. “It’s what I grew up with.” Qin’s parents came to Taiwan by way of the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu during China’s civil war and she grew up eating dan bing stuffed with chopped-up fermented long beans, served with finely minced chilli and a thickened soy sauce flavoured with bean curd. It’s one of the specialities at her family’s shop, which began as a modest stall under an awning 76 years ago and has since expanded into two adjacent shopfronts. One of them, positioned on a street corner, has a deli-style counter, while the other is for those who want to eat in. A solid wall divides the two areas.

Qin’s son, who is now in charge, refreshed the shop recently with a new coat of paint and professionally taken photos of the dishes, displayed both on the menus and in the décor. The food bears plenty of influences from the family’s Jiangsu heritage. Among the highlights are the lion’s head meatballs, a dish that consists of pork with soy sauce and spices. “The meatballs were originally just for the staff but our customers liked them too and now they’re one of our signatures,” says Qin. Traditionally served in a broth with cabbage leaves, they’re now sold by Qin in a sesame-dotted flatbread that resembles a meatball sub. “You have to keep adapting,” she says.

Despite such willingness to adapt, most breakfast shops have remained little changed for decades. That said, a new wave of younger entrepreneurs is taking a different approach. You’ll find Lao Jiang’s House, which is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, not in an old market but on the edges of Taipei’s financial district. The owners are five friends who quit their day jobs to start the business after the coronavirus-related lockdowns.

“Most of us have worked at traditional breakfast shops at some point,” says co-owner Din Tsung-Hsiung. “We just wanted to create something a little different.” Servicing mostly white-collar workers during rush hour and late-night club-goers on the weekends, Lao Jiang’s House has a menu that offers all of the classics but with subtle updates. For example, there’s a dan bing stuffed with spring-onion-scented beef instead of just egg and another with a rice-paper exterior. “It’s stuff that we want to eat ourselves,” says Din.

What to order

‘Dan bing’

Thin flatbread flecked with spring onion, wrapped around an egg and cut into bite-sized pieces.

Soy milk

Served warm, this breakfast-shop staple is made from freshly ground soy beans and comes in sweetened or salted varieties.

‘You tiao’

Fried dough stick with a golden-brown, crispy exterior and a light, airy centre.

‘Shao bing’

Sesame-crusted flatbread.

‘Fan tuan’

Rolls made using sticky rice and packed with pickled vegetables, meat and egg.

What makes Lao Jiang’s House stand out is its décor. With white tiles, light-wood trimmings and solid timber tables, it looks more like a Western coffee shop than a traditional breakfast shop. The space has been carefully designed to encourage diners to linger. Across Taiwan, the idea of a more design-forward breakfast space – albeit with the same level of comfort as the original breakfast shops – is gaining traction. Few do it as effortlessly as Nite-Nite Breakfast, a newcomer that has quietly entered the scene. Tucked away in the Neihu district, it has floor-to-ceiling glass windows and is branded with a smiley-face logo with bright-yellow accents. The dining area is spacious and flooded with natural light, a deliberate counterpoint to Nite-Nite’s often cramped competitors.

“Most breakfast shops are on busy street corners. We chose this spot to help people to unwind,” says Jane Hu, a marketing manager – a position that few old-school breakfast shops employ. When Monocle visits on a Monday afternoon, the shop is full of diners sitting down for their meal. The menu is full of unexpected flavour combinations. There’s a mapo tofu dan bing, stuffed with tofu, minced meat and fermented chilli sauce; we’re also tempted by an egg sandwich featuring pork floss – dehydrated pork with a candy-floss-like texture – and century egg, a preserved duck egg with a distinctive blackish hue.

Traditionalists might scoff at new establishments of this kind (as well as at the tendency of their clientele to take photos of their food) but they are attracting footfall. Perhaps this evolution of the breakfast shop is a quiet rebellion against the sameness of so much brunch culture, with its bland avocado toasts, or the relentless pace of Taipei’s commuter hours? That’s something to discuss over a dan bing, anyway.

Address book

Chongqing Soy Milk and Fried Egg

Known for its deep-fried ‘dan bing’.

32, Lane 335, Section 3, Chongqing North Road

Fu Hang Soy Milk

A traditional favourite with long queues.

108, 2nd Floor, Section 1, Zhongxiao East Road

Lao Jiang’s House

Open around the clock, all week.

110 Yanji Street

Miss Qin’s Soy Milk

Try the signature ‘dan bing’ with long beans.

7-6, Yanji Street

Nite-Nite Breakfast

A quiet place with quirky flavour combos.

37, Lane 127, Gangqian Road