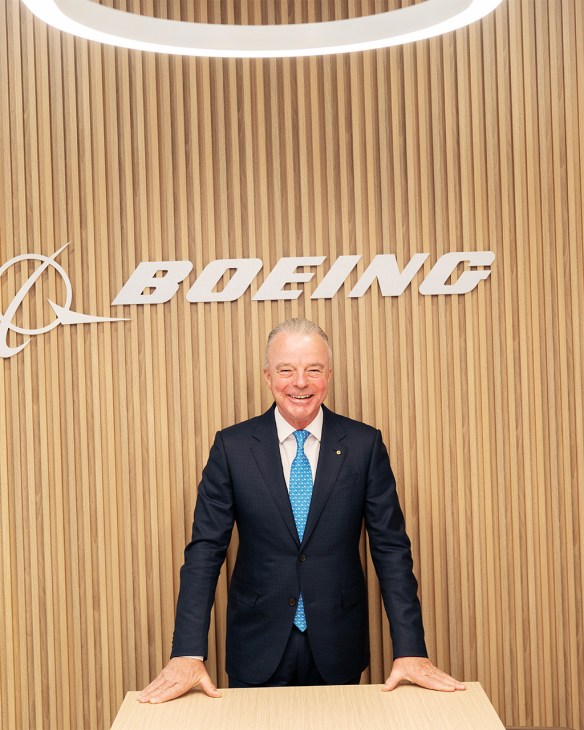

‘We’re not overconfident’: Boeing Global’s president Brendan Nelson on rebuilding trust

As the aviation giant continues to work its way out of crisis, we speak to the company’s president, Brendan Nelson, on what’s next for Boeing Global.

Few aviation giants have endured a bruising like Boeing. The past decade has brought crashes, production stoppages, supply-chain failures, regulatory pressure and a well-documented backlog. Even its most loyal customers, especially in the Gulf, have voiced frustration. But according to Boeing Global’s president, Brendan Nelson, there is a way forward.

Towards the end of last year, the American aerospace giant put on a truly confident display at Dubai Airshow. In one of the vast exhibition halls, a gleaming model of the Boeing 777X sat proudly at the heart of the brand’s pavilion. Guests paused to examine the aircraft’s distinctive folding wingtips and elongated fuselage – a miniature of a superlative machine. This is where Brendan Nelson, Boeing’s senior vice-president and president of Boeing Global, appeared most in his element. He stood beside the model with the confidence of a curator showing off a prized exhibit.

Before our interview begins, he adjusts his bright-blue tie patterned with tiny aircraft and offers a friendly, “Call me Brendan.” Throughout the conversation, he often touches his chin as he listens, eyes fixed and unwavering as if aware that a single misplaced word could send the wrong signal. It is the focus of someone who knows that the margin for error (reputational or otherwise) is razor thin. Nelson is not the typical aerospace executive. A trained physician and a former defence minister of Australia, he combines clinical directness with political fluency: a blend that feels necessary in guiding Boeing back from the brink.

“Dubai Airshow, in many ways, is like a home away from home,” he says. “We’ve had eight decades of partnership with the Middle East and it is exciting to be in a part of the world that has a can-do attitude.” The region has certainly done its part. Boeing’s customer list here reads like a who’s who of Gulf aviation: Emirates, Qatar Airways, Riyadh Air, Saudia, Flydubai. Orders are vast and this year’s event made that clear. Emirates placed its latest eye-watering order of 777-9s worth about $38bn (€32.23bn), a reminder of just how much the world’s biggest long-haul carrier still wants Boeing to succeed. Flydubai committed to $13bn (€11bn) worth of aircraft, with 75 new jets to underpin its next growth phase. And in a sign of how fragile relationships have become, Etihad stepped decisively away from Boeing, opting for a 32-strong widebody Airbus fleet instead, its patience exhausted by repeated delays. Riyadh Air, meanwhile, waits keenly for the arrival of its first Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, the opening aircraft in its planned fleet of 72, without which the new Saudi carrier cannot begin operations in its own fully fitted-out livery. These deals were not casual chequebook diplomacy – they were reminders of both the region’s faith in aviation and its growing insistence that Boeing must now deliver, without excuses.

The past eight years have been among the most difficult in Boeing’s history. The tragedies involving the 737 Max shook the industry’s faith. Pandemic disruptions, workmanship lapses, supplier breakdowns and missed deadlines compounded the sense of a company struggling to meet its own standards, let alone its customers’. Some, like Emirates’ Tim Clark, have been blunt in their assessment: Boeing, he has reminded the world, should fully understand the damage that its failures have caused. “It’s immaterial whether we think it’s fair or unfair,” he says. “Criticism is important. The moment you close your mind and stop listening, that’s when you get into trouble.”

The attitude is refreshing but also necessary. Too many of Boeing’s recent wounds have been self-inflicted. “We’ve had very frank, very open discussions internally,” he says. “Looking at where we didn’t do things as well as we should have and how we can do it better.” This, at least, aligns with what airlines say they want: accountability backed by visible change.

The most significant shift came in August 2024, when Kelly Ortberg took over as CEO. His mandate was to return Boeing to the company that it once was: rigorous, disciplined and quietly excellent. “Kelly said that there are four pillars the future of this company will be built on,” says Nelson. “Culture, stability, execution and thinking about the future.” Resetting production required slowing down, something that Boeing historically resisted. The company introduced new quality metrics, paused entire lines to hear from frontline employees and invested heavily in training and tooling. “We listened to our staff and implemented the ideas they put forward,” he adds. “We’ve stabilised the balance sheet and the production line.” But he refuses to celebrate prematurely. “I don’t want anyone to think that there is any sense of overconfidence in us,” he says. “We are confident but not overconfident.” For an organisation previously accused of hubris, that distinction matters.

But if Boeing has a safety net, it is the Gulf. “This region, our customers, the governments – they remained very committed to Boeing, even through the challenges,” says Nelson. “Our biggest challenge,” he adds, “is producing the 6,000 backlog of planes as safely and efficiently as we can.”

Outside, on the runway, Boeing’s most important aircraft did something it hasn’t been allowed to do much in recent years: impress. The long delayed, long criticised, long awaited 777X climbed into the clear desert sky with surprising grace for a jet of its size. It banked, levelled and swept past the crowd with a self-assurance that the company itself has lacked for too long. Back inside, Nelson watches with calm pride. “People have been saying to me, ‘It’s great to have Boeing back,’” he says. “We’re a company that’s turning, you’ve seen significant improvements in production quality and safety.” But then comes the caveat, delivered with characteristic bluntness: “We’ve let down customers at times. We’ve eroded trust. I’m confident that it is being rebuilt but we still have work to do.”

Boeing’s future plans are measured rather than revolutionary. The company is focused on steady delivery, refining its current portfolio and building the technological foundation for the next generation of aircraft. “These aircraft – the 737 variants, the 787, the 777X – will be significant for the next 20 to 30 years,” says Nelson. There is no rush to unveil something radically new. Not until Boeing can guarantee that it works every time, on time.

Boeing begins 2026 with renewed attention, warmed relationships and a hint of regained respect. But respect is not the same as redemption. And despite signs of recovery, it has not yet earned the right to declare itself fully restored. The company is moving forward but carefully. The industry is watching but sceptically. And customers are ordering but insistently.

Beneath the optimism sits an undeniable truth: Boeing is only at the start of its repair job. Trust, once lost, is not rebuilt by an airshow performance. It is rebuilt aircraft by aircraft, delivery by delivery, year by year. For now, Boeing looks more grounded and self-aware than it has in years. But the world will wait to see if that momentum endures, long after the desert dust settles and the crowds go home.

In brief, here’s what Nelson sees on the horizon:

Tackling the backlog

Boeing is sitting on a mountain of aircraft to be delivered – more than 6,000 jets, with 975 earmarked for Middle Eastern carriers. “Our biggest challenge is producing those planes as safely and efficiently as we can,” says Nelson. It’s “a good problem to have” but one that stretches into the next decade.

New deals and Middle East confidence

Gulf support for Boeing never dried up. Emirates placed a $38bn (€32bn) order for 777-9s, Flydubai committed $13bn (€11bn) for 75 aircraft and Riyadh Air is awaiting the first of its 72 Dreamliners. But Etihad’s pivot to a 32-strong Airbus widebody order underscored that the goodwill has its limits.

Rebuilding trust

Boeing has already begun to reset its culture, says Nelson: slower production, new quality metrics, stand-downs for 70,000 staff and a reshaped leadership. “We’re turning,” he says, “but we’re not overconfident.”

Read next: Airlines today are creating a generation of disloyal customers