Ten disruptors taking aim at modern warfare

As global alliances shift and technology redefines the battlefield, Europe’s defence industry is stepping up to offer smart new solutions. Here are a few of the innovations currently on our radar.

The heat is on for Europe to start taking its own defence and security more seriously, with the US signalling that it will no longer be the guarantor of peace on the continent. European defence stocks are soaring as investors watch budgets track up for the first time in years. Countries claim that they want to “buy European” – yet those shopping around for new kit soon realise that while there are big local players such as BAE Systems, Thales and Dassault Aviation, the ecosystem of defence start-ups is less developed in Europe than in the US. There’s clearly some catching-up to do.

Here, Monocle rounds up 10 firms that could become the vanguard of the continent’s defence industry. Whether they’re creators of armour, walkie-talkies or counter-drone technology, the following have caught the attention of venture capitalists, helping them to scale up to meet the moment.

1.

The up-and-comer

Tekever

Portugal

Portuguese defence firm Tekever started out building software before shifting into drone technology in 2010. According to its CEO, Ricardo Mendes, those beginnings planted the seeds of its success. “Good software companies are agile to their core,” he says. “Just look at your phone. You get a new update every two to three weeks and, if you don’t, it starts to lag. That attitude to development is how we approach our work.”

In 2018, Tekever signed its first contract with the European Maritime Safety Agency to run drone patrols over European waters, collaborating with Collecte Localisation Satellites, France’s space agency subsidiary. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that began in 2022 boosted business as demand for hi-tech reconnaissance drones soared. Tekever has since expanded its Portuguese presence, rolled out a UK-based manufacturing hub and picked up investment from the Nato Innovation Fund and early SpaceX backer Baillie Gifford.

When Monocle visits Tekever’s facility in Wales, which opened in 2023, employees are hard at work on its AR3 surveillance drone. “We manage the entire process,” says Tekever’s deputy head of defence strategy, Phil Hanson. “The AR3 drone being used in Ukraine has gone through more than 100 iterations. We take feedback from customers 24/7, allowing us to update our products rapidly. That’s pretty much unique in the market.”

Tekever might be an emerging firm but it has illustrious neighbours. Nextdoor to the Wales facility is French defence giant Thales; from a meeting room, we catch sight of a 6.5-metre WK450 drone that Thales produced with Israeli military technology company Elbit Systems. That project was retired from service earlier this year amid rocketing costs – well before its scheduled end-of-service date of 2042. “There is a growing frustration with the present way of doing things,” says Hanson, who believes a fresh approach is needed – and which Tekever, with its agility, cost-effective mindset and urge to improve, is practising.

Mendes also believes this is a time of great opportunity for European defence firms such as his. “The nature of war and defence is no longer compatible with long development and procurement cycles,” he says. “The market model has changed and we’re moving away from defence monoliths. What Europe needs now are companies that can move fast, scale up and work together in an ecosystem.”

tekever.com

2.

The delivery guys

Arx Robotics

Germany

Last-mile delivery is a sector that’s full of opportunities, whether that’s doorstep drop-offs or getting military supplies to the front line while under fire. During his time at the start-up incubator lab at Bundeswehr University Munich, which is run by the German Armed Forces, former army officer Marc Wietfeld wondered whether robots could be put to this dangerous task.

As Wietfeld explored the robots’ potential for logistics, he sought to raise funds for a large prototype. In March 2022 he teamed up with Max Wied, another army officer with a background in finance. Stefan Roebel, who cut his teeth in business at Ebay and fashion retailer Asos, joined in 2023. A few years later, the company they founded, Arx Robotics, has already broken several records, including for funding and deliveries to Ukraine, where its robots now carry ammunition, sensors or aerial drones into combat and wounded soldiers out of harm’s way.

business development

The success of Arx’s Gereon robots is down to their autonomous capabilities, which are facilitated by a mix of artificial-intelligence software, night-vision stereo cameras for a 3D view, and thermal and lidar sensors for obstacle recognition. Crucially, they are also inexpensive to build, as the software easily integrates with third-party products and the hardware is mostly made up of off-the-shelf industry components. Initially, Arx set the cost of a robot at between €30,000 and €150,000, depending on features and sensors. Today, says Wietfeld, “They cost a sixth of our cheapest competitor.”

Arx robots have all-terrain tracks, a maximum speed of 30km/h and a range of 40km. The modular mounted section of the robot can be swapped out by hand in just two minutes and can be modified to carry a stretcher for evacuations, sensors for reconnaissance, a launcher for aerial drones or a basket for supplies of up to 500kg. The firm rapidly attracted supporters and capital. In September 2023, Project A, a Berlin-based technology VC company, invested €1.15m. Nine months later, Discovery Ventures, another VC from Berlin, and the Nato Innovation Fund (see below), along with Project A, put forward joint seed investment of €9m – the largest seed round for a European defence-technology company to date. In early 2025, Arx sent 30 robots to Ukraine. The delivery from Germany was the biggest autonomous ground fleet provided by any Nato country.

Since then, Arx has established a 10-person team in Kyiv to oversee maintenance and production and gather feedback. It found that limiting the size of the robots to about 1.3 metres makes them harder to detect and more easily deployable by civilian vehicles.

Arx is increasing production in Germany and Ukraine and setting up in the UK, and recently inaugurated Europe’s largest plant for unmanned ground systems in Erding, near Munich, which is becoming a hub for defence start-ups. In April, Arx secured a second funding round of €31m to quintuple its production capacity and raise its workforce from 60 to at least 100 employees by the end of 2025.”

arx-robotics.com

Investing in defence

European venture capital has in the past been wary of investing in start-ups that make products with links to warfare. But the invasion of Ukraine changed that. According to a 2024 report from the Nato Innovation Fund and Dealroom, European investment in the defence, security and resilience sector totalled €4.5bn in 2024, an all-time high. Here are five funds to know.

1.

MD One Ventures

Europe’s first VC firm dedicated to national-security start-ups has backed everything from quieter jet engines to AI.

2.

Nato Innovation Fund

Backed by 24 allies, this fund has deployed more than €1bn in hypersonic systems and next-generation communications.

3.

Scalewolf

The Lithuania-based accelerator invests in dual-use technologies with defence as well as commercial applications.

4.

National Security Strategic Investment Fund

This UK government-supported venture fund has backed breakthrough companies in drones and next-generation defence manufacturing.

5.

Hyperion Fund

This Spanish fund launched in 2024 with €150m growth equity and focuses on aerospace, cybersecurity and AI-related defence firms.

3.

The frontier steward

Frankenburg Technologies

Estonia

Being “mission-driven” has become a cliché among start-ups – jargon trotted out by ambitious founders and written in pitch decks. At Frankenburg Technologies, a defence start-up based in Tallinn, Estonia, the phrase feels more like a battle cry. “We are a single-use company with a single mission: to defend Europe and equip the free world with the technology to win the war,” says Kusti Salm, the firm’s CEO. As he speaks, he presents a prototype of the company’s first product: a missile designed to shoot down drones such as the low-cost Iranian-made Shahed deployed by Russian forces in Ukraine. In contrast to the traditional military-industrial model – which is heavy, slow and expensive – Frankenburg promises guided-missile systems that are 10 times cheaper and 100 times faster to produce.

Estonia, once occupied by the USSR, now has more start-ups per capita than any other country in Europe. Frankenburg represents a convergence of that technology-forward spirit with a frontier nation’s understanding of regional security. The company was launched in 2024 by a formidable trio – a former high-ranking defence official in Estonia’s military, a veteran rocket scientist and one of Estonia’s wealthiest entrepreneurs – and has moved with the urgency of a start-up. In just a few months, its valuation has tripled to €150m. Several funding rounds have been announced, with plans to scale operations across Europe. The company is establishing research and manufacturing facilities in Latvia and opening a new headquarters in the UK. The company also has plans to test its missile systems in Ukraine, in co-operation with the country’s Ministry of Defence.

Frankenburg has a staff of about 50. Many of its employees are ex-military leaders and top engineers drawn from the private sector and academia. According to Salm, his team’s modest size makes the company nimble. “We’re faster, more flexible and not locked into outdated models,” he says. While Russian factories churn out low-cost drones by the hundreds of thousands, Europe’s air-defence systems are complex, prohibitively expensive and too slow to scale. “Europe is behind and, unless we invest trillions in defence capabilities, we’ll stay behind,” he adds.

Unlike conventional missile systems, Frankenburg’s products are intended to be scalable, partially disposable and manufactured using commercial components. Many of the sensors in its missiles, for example, are the same as those found in smartphones. The company also relies heavily on 3D-printing and rapid prototyping to slash costs and to iterate quickly. “There is no time to waste,” says Salm. “We can’t afford to move at the pace of traditional procurement cycles. The battlefield is changing now.”

frankenburg.tech

More European defence-technology firms to keep your sights on

4.

Greenjets

UK

Drones might be reshaping battlefield planning but the wasp-like buzzing of an unmanned autonomous aerial vehicle hardly makes for a stealthy entrance. UK-based Greenjets, which was founded in 2021, saw an opportunity to address this and is developing electric-powered jet engines for vertical take-off and landing that emit just a third of the noise.

The company launched its first engine of this kind in 2023. Designed to power the next generation of small unmanned aircraft, the IPM5 was inspired by the helicopter-shaped seeds of sycamore trees, which the wind can carry great distances. Its ducted-fan architecture helps to keep the volume down while making it safer and more secure than conventional engines with open-bladed propellers.

Though it weighs just 750g in total, the IPM5 efficiently provides plenty of thrust. It is now shipping to drone manufacturers. The company plans to eventually roll out models for larger aircraft that are capable of carrying passengers; it has released renders of a futuristic-looking “air taxi” and a timeline to have them aloft by 2028. That might sound ambitious – but there’s nothing wrong with aiming for the sky.

greenjets.com

5.

Pangolin Defense

France

Ballistic-protection specialist Pangolin Defense’s signature vest can take a pummelling. It incorporates glass scales to create flexible ballistic plates that make for comfortable and affordable bulletproof armour. Founded in 2020 by four students, Pangolin Défense received an early grant from the French ministry of defence that allowed it to manufacture everything in the country.

The company now makes 3,000 vests a month, which it supplies to militaries and police forces across the globe, as well as the UN. It has also recently expanded into the US. “Our goal is to win a major national or European public tender before the end of the year,” says co-founder Clément Saglio. “That will get us a seat at the big kids’ table.” The war in Ukraine led to a spike in demand and Pangolin Défense has doubled its revenue over the past two years.

pangolin-defense.fr

6.

Himera

Ukraine

Kyiv-based walkie-talkie maker Himera launched in 2022 to solve a problem: Ukrainian soldiers had few effective, cheap and reliable ways to communicate. “You can have the most sophisticated weapons and equipment but if you can’t co-ordinate, most of that becomes useless,” says Himera’s co-founder Misha Rudominski.

The company offers radio and communication devices that are resistant to external interference, such as that from Russian troops, as well as cheap to produce. In 2024 it announced a deal with Ottawa’s Quantropi to distribute its products in the US, Canada and selected Nato markets. Being based in Ukraine is an advantage to the business. “It has given us the best understanding of how our products work in practice,” says Rudominski. “Our users write to us from the battlefield, reporting any problems. We take that information on board and fix things.”

himeratech.com

7.

Helsinki Shipyard

Finland

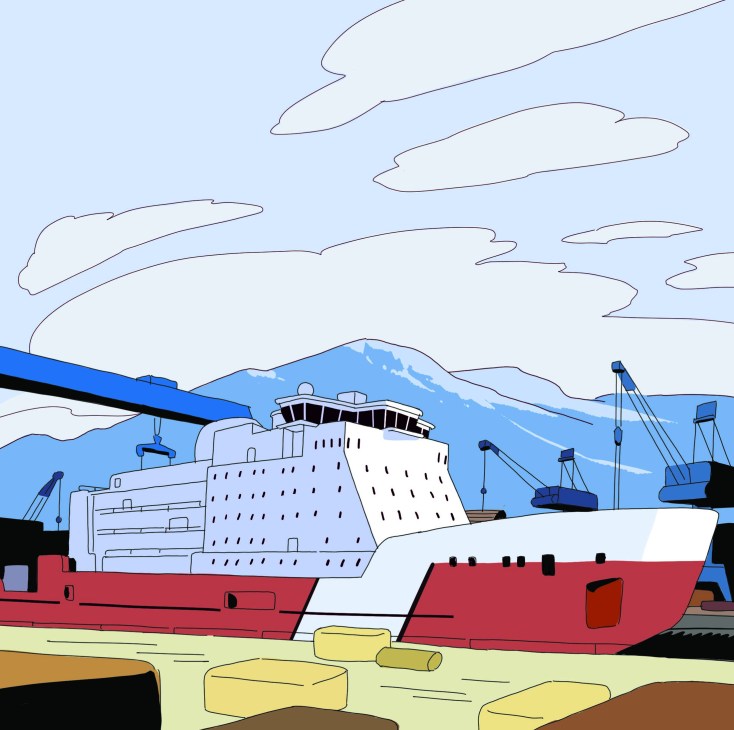

Icebreakers are key to navigating the Arctic. Helsinki Shipyard is a historic builder that, until 2023, was owned by Russians and was heavily affected by sanctions. That year it was acquired by Québec-based firm Davie, which has been building ships in Canada since 1825. Its first new vessel, the Polar Max, will be delivered to the Canadian coast guard in 2030. “The door to the Arctic is wide open and the West isn’t winning the race,” says Davie’s Paul Barrett. “We’re looking to accelerate joint shipbuilding efforts on both sides of the Atlantic, with a view to securing the strategic interests of the West in the High North.”

davie.ca

8.

Nordic Air Defence

Sweden

Swedish start-up Nordic Air Defence’s Kreuger 100 is a battery-powered, non-explosive drone interceptor that relies on built-in software to locate its target and knock it out of the sky. It’s named after Swedish tycoon Ivar Kreuger, who built a business empire on matches. “He took something potentially dangerous and made it safe, mass-manufacturable and cheap,” says the company’s business director Jens Holzapfel. “We will do the same with counter-drones. In Ukraine, it’s a numbers game right now. To compete, the countermeasures against drones must be cheaper than the actual threat – or, at least, not exceed its price.”

nordicairdefence.com

9.

Helsing AI

Germany

Founded in 2021, Munich-based Helsing AI is among Europe’s leading defence start-ups and was valued at €5bn last year. It creates AI software for battlefield planning that’s capable of crunching vast amounts of data from sensors and weapons systems, enabling split-second decision-making. It has also been used to co-ordinate drone “swarms” in Ukraine. Both a technology and a hardware company, Helsing makes products, such as its HX-2 drones, at “resilience factories” designed with local supply chains in mind.

The firm received support from venture-capital fund Accel, an early backer of Facebook and Spotify, and has partnered with French-American space start-up Loft Orbital to deploy Europe’s first AI-powered multi-sensor satellite constellation. In collaboration with Swedish aerospace firm Saab, Helsing is set to upgrade the electronic-warfare capabilities of 15 of the German Luftwaffe’s Eurofighters.

helsing.ai

10.

Space Forge

UK

Space Forge is a young company that is reviving an old idea: manufacturing in space. Its focus is the crystals that go into compound semiconductor chips, which are crucial to the energy-intensive radar and communication systems used by the defence industry, as well as by AI. “All of the things that make Earth a lovely place to live, such as gravity and the atmosphere, are terrible for almost any industrial process,” says Joshua Western, co-founder of Space Forge. Growing these crystals in space, he adds, is far quicker, with a lower risk of impurities.

In the summer, Western’s team will send its Forgestar-1 grower into orbit. Though still testing its product, the start-up has attracted industry interest and is collaborating with US defence giant Northrop Grumman. “Semiconductors are the oil of the 21st century,” says Western. “They underpin all critical infrastructure and whoever has the best material to make the best chip has the biggest edge.”

spaceforge.com