Could an athlete influence you to buy a leather handbag? Earlier this month, Bottega Veneta tapped Italian pro tennis player Lorenzo Musetti as its latest brand ambassador – a strategic marketing move announced on the day that he took to the court at Wimbledon. In London, he stepped onto the court in a white intrecciato leather bomber jacket for his first (and, sadly, last) game of the tournament. Aged just 23, Musetti joins Bottega Veneta’s prestigious stable of brand ambassadors, including South Korean singer I.N (of boy band Stray Kids) and Australian actor Jacob Elordi. Meanwhile, Wimbledon title winner Jannik Sinner’s walk-on moment featured an oversized Gucci bag. A global brand ambassador for the Italian house since 2022, his victory no doubt raised the spirits of the label’s marketing team as it gears up for a new chapter under Georgian designer Demna.

Fashion brands leveraging athletic prowess to associate themselves with technical excellence is nothing new. Basketball player Michael Jordan arguably pioneered the modern form of celebrity sponsorship when he signed his first deal with Nike in 1984. But the phenomenon has gained traction in recent years, replacing unapproachable Hollywood stars or online influencers with little more than follower counts on their lists of achievements. Who would you rather work with: a temperamental starlet or a punctual athlete? Carlos Alcaraz reps Louis Vuitton, alongside fellow tennis prodigy Naomi Osaka. In 2021, UK wunderkind Emma Raducanu clinched a US Open title along with a Dior ambassadorship, though the French house has since replaced her with Chinese player Qinwen Zheng after Raducanu failed to recreate the buzz surrounding her early-career wins. More recently, Italian brand Canali selected Greek tennis player Stefanos Tsitsipas to be its very first brand ambassador.

Paris’s Summer Olympics pushed the fashion industry’s interest in sports to fever pitch. French luxury conglomerate LVMH was a major sponsor of the games. The opening ceremony saw French athletes dressed in Berluti and performers, including Celine Dion and Lady Gaga, in Dior. LVMH-owned jewellery-and-watch house Chaumet crafted the medals, which athletes received in a bespoke Louis Vuitton trunk, évidemment.

In the contemporary marketing landscape, a pivot to sportspeople for inspiration and brand loyalty makes sense. Yes, models make for beautiful campaigns and we all harbour the hope that we might look like Vittoria Ceretti if only we wore the exact same Gucci dress. But being born gorgeous isn’t a form of merit that can compete with the discipline, dedication and exceptional skills of athletes. For many brands, sportspeople are a way to signal their own technical expertise and the pursuit of excellence.

A brand ambassador can also provide credibility. Swiss luxury-watch label Richard Mille works with French freediver Arnaud Jerald, who breaks records wearing an RM-032 and vouches for the watch’s ability to withstand watery depths in the process. French alpine skier Alexis Pinturault competes with an RM 67-02, putting the timepiece to the test as he whacks poles while slaloming down snowy slopes at breakneck speed. Whether or not office-working Richard Mille watch owners need this level of technical durability is another matter. It’s knowing that, if so desired, these technical marvels could sustain such strain.

Finally, with the fashion industry worth a reported €1.45trn and the sports world valued at €2.26trn, the maths behind this trend of cross-marketing is clear. Gaining visibility in an arena, stadium or on a court is simply a good investment. Sports fanatics are exactly that: fanatics. For many, the agony and the ecstasy of a game or match is akin to a religious experience, their favourite players saints or, in one case, a Sinner. For now, the luxury fashion houses have kept their sights on more elitist sports. But as marketing budgets shrink, brands might become more strategic with who they select to represent them. Whether or not these brand-ambassador deals will extend to the world of darts or video games remains to be seen.

This week I’ve been travelling around Aragón in northeastern Spain, visiting some of the people I wrote about in Monocle three years ago for a piece about the fight against rural depopulation. This vast expanse of yellow scrubland and verdant forests is at the heart of what the local press calls la España vaciada (literally “the emptied Spain”). Since the years of the Franco dictatorship, people have been decamping from their ancestral villages to the big cities in significant numbers. But, as I have learned over the past few days, it’s a mistake to assume that the Spanish countryside is dead and buried.

Spain, of course, has huge demographic issues. Like Italy, where I live, it has a low birth rate and an ageing population. Between 2010 and 2019, populations have fallen in nine regions of the country, including Aragón. There are almost 7,000 municipalities in Spain with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. Yet visit many villages in Spain today and you wouldn’t know it. In Torralba de Ribota, one of the stops on my trip, I find streets full of children playing and running from house to house. The adults, meanwhile, are knocking back ice-cold Ambar beers in the neighbourhood bar. The community swimming pool is packed as locals cool off from the intense heat.

Summer is the peak season of Spanish rural life, when communities across the country hold celebrations called fiestas patronales (patronal festivals). The kids I see running around are the grandchildren of the old-timers who remained; among the others are visitors who own a second house in the countryside but only use it seasonally, having long ago moved to Madrid, Barcelona or Zaragoza. Torralba de Ribota’s permanent residents joke that every year they meet people who swear that they will buy a house and move here – only for the promise to fade away as the air turns chilly come October.

I’m here to see people who have made Torralba de Ribota their home. Many of them had no prior links to the village beyond a knowledge of Lucía Camón, an actress and the founder of an annual cultural festival called Festival Saltamontes, which took place last weekend. Since Camón’s move from Madrid with her former partner and daughter, Torralba de Ribota – which has a population of 169 – has welcomed everyone from a South Korean painter to a stand-up comic and scriptwriter. A couple in their twenties are the latest to move in.

Torralba de Ribota is lucky in many ways. It might seem to be in the middle of nowhere but it’s a short drive from the town of Calatayud, which has several fast trains a day that go to Madrid or Barcelona. In other words, Spain’s main metropolises are within easy reach for a meeting or a retail fix.

While having a creative job that you can do from a studio, workshop or computer clearly makes life in places such as this more viable, comedian Quique Macías says that what the countryside really offers is the chance to take risks. He bought his house for a fraction of what he would have paid in a city and recently purchased a strip of land, where he is now growing pistachios and almonds. He is able to take on only the jobs that he wants to do because he isn’t overburdened with high living costs or an extortionate mortgage.

At a time when the news agenda is packed with stories about geopolitical turbulence and a cost-of-living crisis, village life offers a quieter alternative. This is a place where generations help each other and the pace is slower, more considered. Torralba de Ribota isn’t for everyone and its charms are unlikely to reverse Spain’s demographic trajectory – but its newest inhabitants are proof that another way of living is possible.

Stocker is Monocle’s Europe editor at large. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

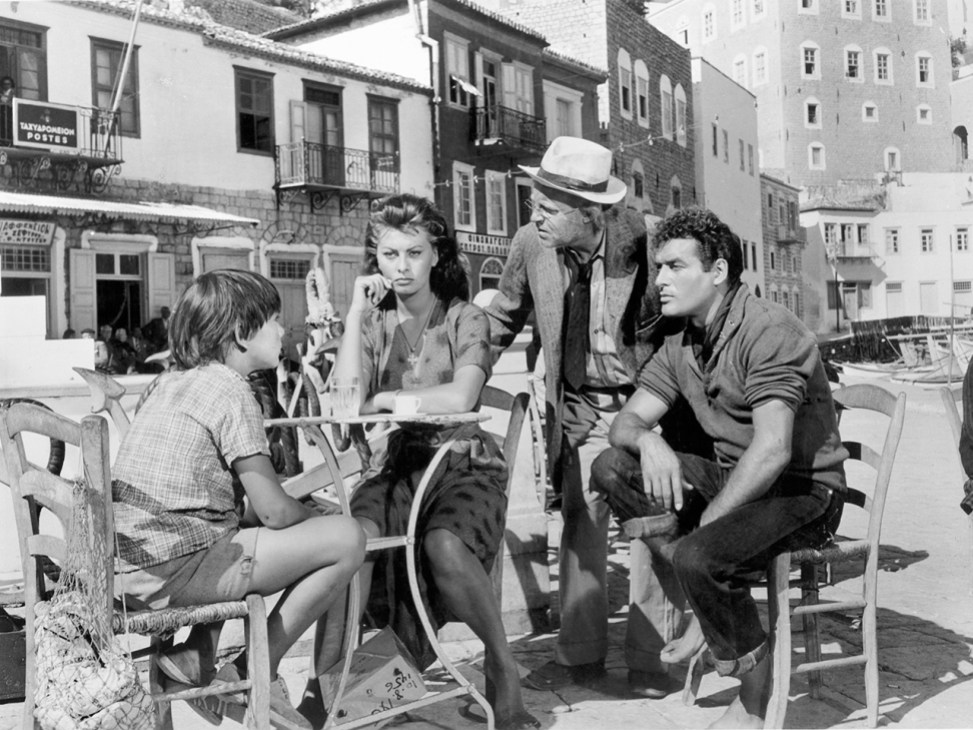

With a smile, George Koukoudakis, the mayor of Hydra, nods to a heavy bronze sculpture on his desk. The piece, which depicts a boy sitting atop a dolphin, was gifted to the island’s town hall in the mid-1950s by members of a film crew from US film studio 20th Century Fox. They, along with a young Sophia Loren, had disembarked on this Saronic island to shoot Jean Negulesco’s romantic drama Boy on a Dolphin, released in 1957. It was the Italian starlet’s debut English-language role and the first Hollywood production to be shot in Greece. Like many of his compatriots, Koukoudakis believes that the picture not only changed the way that the world saw his country but also helped to birth its tourism industry. “The film had such an impact,” he says. “People saw Greece in a different way and wanted to visit. It was the Hollywood effect.”

A restored version of Boy on a Dolphin has been rereleased in Greek cinemas this summer. Almost 70 years on, the scenes of Hydra in glorious DeLuxe Color continue to stir the soul. Athens, Rhodes and Delos also feature, bathed in sun and set against the shimmering sea. One can imagine the effect that such sights must have had on postwar audiences across the globe. Films have the power to take viewers somewhere new, serving as ambassadors for places – think the New York of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the Hong Kong of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love or even Danny Boyle’s dream-like vision of Thailand in The Beach.

Cinema was once a celebration of travel, journeys and placemaking. If this feels inaccurate today, it’s partly because the industry has become less reliant on location shoots and increasingly mindful of budgets. Generic backdrops or green screens can ape the grandeur of a Manhattan crosswalk at a fraction of the cost. Meanwhile, generous tax rebates are luring productions to vast sets in countries such as Saudi Arabia. And budding filmmakers can always take the short cuts offered by generative AI.

It might be the case that today’s cinemagoers are simply better travelled than postwar audiences and that exotic locales are no longer enough to attract them. But don’t underestimate the ability of a major location shoot to bring fresh energy to a place. In Hydra – an island that’s proudly car-free and has remained relatively unchanged for decades – the power of such placemaking endures. The filming of Boy on a Dolphin is part of its lore and older locals, some of whom were recruited as extras during production, still tell stories of what happened when the big Hollywood crew and actors came to town.

In a memoir by Australian writer Charmian Clift, one of the many artists who flocked to the island in the 1950s and 1960s, she describes how Loren’s star appeal caused a flurry on the minuscule island that didn’t even have running water at the time. It’s a reminder to young directors and filmmakers that there’s a big world out there – and plenty more places to put on the map, far beyond the well-documented boulevards of Los Angeles or Paris.

In the Saronic Islands, Loren-loving Greeks are indulging in nostalgia as they settle into cinema seats to rewatch the remastered Boy on a Dolphin. Go and see it yourself for a taste of Hollywood’s golden age, when filmmakers wanted to whisk you away to somewhere new.

Fitzgerald is Monocle’s North Africa correspondent. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

The baguette is a unique French icon. It would be gauche, however, to compare this humble yet noble loaf to a film star, a king or a celebrated artist because its appeal lies in its perfection of ordinariness. In this way this stick of bread, which typically measures about 65cm in length, is also a design classic in a slender pantheon.

It is a robust and unchanging doughy redoubt in a world in which fads and fashion have eagerly sought to reinvent the culinary wheel and deconstruct the gastronomic classics so that we can all, à les Américains, have an order of everything on the side. But no: the baguette offers a reassuring shrug. It is what it is. The traditional baguette is made from wheat flour, water, salt and yeast. It’s the sort of culinary product that contains so few ingredients that its elements have nowhere to hide in its making and then in the final, joyous eating. The boulangers apply their scrutiny and formidable skills to these constituent parts, which come under some 230c of heat.

The baguette de tradition Française has made a considerable comeback in this era of people wondering whether factories – which we all agree are fine for building cars, say, or computers – might not be the best places to make food. So the additives, preservatives and general nonsense that prevail in some baguettes are derided rather than devoured by the artisan bakers of France and their millions of hungry devotees. Glance at the list of ingredients, say the bakers. If it seems too long, then it most certainly is.

The baguette is also emblematic of larger ideas that the French hold dear. It is something of a human right. It is the daily bread of the Lord’s Prayer, the staff of life. It is simple enough to be perfect for breakfast, lunch or dinner too, adept at being the vehicle to deliver your beurre sel et confiture or a happily messy slice of chaource cheese. But it will probably still emerge as the star.

The baguette’s status as a national staple has unsurprisingly been enshrined by a country that knows what it is good at and what is good for it. In 1920, France put in place a price cap to ensure that everyone could eat it; this was only lifted in 1987 but the belief in people’s inalienable right to a baguette endures.

In recent years of energy price rises and Europe-wide inflation, the baguette has become something of an economic bellwether. News crews and researchers in France scrutinise it, while wags overseas find it mildly amusing that – of course – they’re up in arms about French sticks.

In Paris, as in the rest of the country, you can pick up a baguette for less than €1 at a supermarket. The chances are that it’ll be a slightly saccharine flute – edible but nothing special. Instead, you should visit a boulangerie and ask for un tradition. For the slightly higher cost of about €1.30, you will receive in your hand what Emmanuel Macron once described as “250g of magic and perfection” (what a relief it is that he didn’t choose to measure its qualities by length). That’s a small price to pay for the keys to an unimprovable culinary kingdom. The baguette, simple yet highly effective, is a great leveller.

Out and about in Paris, hungry and with an eye on the culture of the boulangerie – particularly the status of the baguette in a city well known for its deathless traditions and nimble transformations – Monocle walked and saw and ate and asked. Bakers told us how they bake it; customers described to us how they eat it and when. We learned about the daily ritual of the boulangerie visit to purchase le pain quotidien, that secular sacrament, that bastion, that baguette.

Three of the best bakeries in Paris

Du Pain et des Idées

This bread-making, bread-breaking shop was opened in 2002 in a boulangerie that dates back to 1875 by Christophe Vasseur, who is something of a saint in Paris’s cloistered world of contemporary bakers. Vasseur offers bread, patisserie and a little viennoiserie – the key to the latter being a flaky finish achieved with 30 hours of fermentation. Just 60 baguettes a day are made here for the delectation of quick-moving flute-fanciers.

dupainetdesidees.com

Union Boulangerie

Maëva Manchon and Charles Ye were studying neuroscience and finance, respectively, when they decided to quit to get their hands dusty baking bread. “We had one chance to do what we really wanted,” says Manchon. Their first bakery, which opened in 2021, is a stripped-back, naturally lit corner plot in the 9th arrondissement that satisfies office workers, well-dressed locals and cool dudes alike. (A second outpost will open later this year.) It bakes 500 baguettes a day. “I can count on one hand the days when we haven’t sold out,” says Manchon. The goods look heavenly on the bakery’s simple wooden or glass stands. “Why would we hide this stuff up on a shelf?” asks Ye. “We’re all about transparency and quality. We have nothing to hide.”

instagram.com/unionboulangerie

Terroirs d’Avenir Boulangerie

Delphine Pereira runs four bakeries in Paris for the much-admired Terroirs d’Avenir food-shop chain, which was co-founded by Alexandre Drouard and Samuel Nahon. “We have all loved baguettes since we were children,” says Drouard. “We love to eat them while they’re still warm so the crust is still crunchy and the crumb is soft and airy.”

When Monocle visits the company’s Rue du Nil bakery, the hum of machines is nowhere to be heard. “We prepare our baguettes entirely by hand, without machines for dividing or shaping,” says Drouard. “It’s a skill that has almost disappeared.” In what must be an endurance trial for the bakers, between 300 and 500 baguettes are mixed, cut and kneaded a day at every one of Terroirs d’Avenirs’ four boulangeries. We’re expecting its workout regime to hit the internet very soon.

terroirs-avenir.fr

Hollywood’s financial model is a many-tentacled, fast-evolving beast. Its true motives are kept intentionally opaque and its fortunes are often inscrutable even to those behind the studios’ gates. However, when what emerges is the world’s pre-eminent art output, understanding its economic motives is to parse a global impact that shapes everything from fashion to foreign policy and even our own neuroses.

A project’s commercial fate can remain a mystery long after its premiere. Even the creators of the 1997 smash hit Men in Black have said that they are told annually that their film has continued to “lose” money over the years, preventing them from profiting from its $600m (€509m) box office. Consider Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav, whose 2021 compensation package totalled $246.6m (€209.3m). The following year, he shelved completed films to capitalise on tax incentives – a cursed echo of Mel Brooks’s The Producers, which in 1967 cheekily suggested that it was easier to profit from a flop than a hit. In other words, the gatekeepers of the world’s most popular artform found a way to monetise empty cinemas.

The rise of streaming has further blurred the lines by keeping viewer numbers hidden, shortening theatrical-release windows and muddying already murky accounting waters. With ballooning marketing budgets and diminishing returns, studios have been compelled to look elsewhere for steady revenue. Brand tie-ins, product placements and sprawling IP libraries can contribute as much, if not more, than ticket sales. This dynamic has transformed the kinds of films that are being made. Much of cinema’s output has split into two camps: childish tent-pole blockbusters designed to sell everything from trainers to theme-park churros, or smaller-budget releases from A24 or Blumhouse, which cost under $10m (€8.5m) and only need to occasional success to stay viable.

In recent years, this shift has squeezed out the mid-budget Hollywood film (generally defined as one with production costs between $10m and $100m (€8.5m and €85m). Matt Damon lamented back in 2022 that, without DVD sales, titles such as The Talented Mr Ripley, The Informant! and Behind the Candelabra, which had once been his “bread and butter”, were no longer economically viable. As a result, Damon started cropping up in franchises like Thor, and we saw him in fewer period dramas, taut thrillers and romantic comedies. Merchandisable IP became the new movie star.

But in a rare win-win situation between audiences and capitalism, change is afoot. After a series of crises – including coronavirus lockdowns, industry strikes and wildfires – there’s a new glimmer of hope. One strange perk of studios owning so many parts of the entertainment pipeline is that they can leverage synergy. For example, NBCUniversal owns a wide array of international television channels across broadcast, cable and streaming, along with podcasts, ticketing platforms and even the review website Rotten Tomatoes.

So, while a mid-budget flick might not gross as much as the latest Fast & Furious instalment, NBCUniversal can milk it for every cent across its ecosystem by placing its stars on in-house talk shows and podcasts, driving audiences to check the film’s score on Rotten Tomatoes and then directing them to buy tickets directly through its websites. Every viral moment from Jimmy Kimmel Live!, SNL or The Kelly Clarkson Show is more cash in the studio’s pot, making mid-level productions a less risky proposition. It’s a brazen confluence of art and commerce that might just resurrect the rom-com.

Certain tax incentives around the globe can also reduce production costs. Many US game shows are now being shot on the Emerald Isle, as it’s cheaper to fly contestants and hosts from California than to film on a Los Angeles sound stage owned by Fox Broadcasting Company. And while this shift is great news for those locales, it threatens swathes of working-class jobs in Hollywood, with many production workers struggling to earn a living. The result is mounting pressure to create similar tax incentives in California (Donald Trump’s “100 per cent tariff” on non-American films is a non-starter).

Now, with mid-budget films seen as lower risk, there’s more incentive to make them. Well-reviewed, inventive releases such as Sinners, Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy, The Monkey and 28 Years Later have all earned ample returns on investment, proving that the box office still matters and that the industry doesn’t have to focus on how many tie-in Lego sets that it can sell. Sinners’ creator Ryan Coogler, Hollywood’s man of the moment, recently avoided the pitfalls of “Hollywood accounting” by negotiating “first-dollar gross” (a practice in which actors and producers take a percentage of gross box-office revenue from the first dollar made) rather than waiting for the studios to admit to making a profit.

The deal made by Coogler also stipulated that the rights to Sinners will eventually revert to him, rather than being absorbed into an IP vault. This ownership model prioritises theatrical revenue, with the myriad other ways the vampire flick can generate cash treated as the icing, not the cake.

Given its unpredictable nature, 21st-century media could look radically different in just a few years – but there are reasons to be optimistic. Mid-budget titles such as The Smashing Machine, Eddington and others are jostling to become this autumn’s Sinners. But audiences will need to vote with their wallets if we want more starry films made for grown-ups. So let’s ride the wave of this exciting new era and go to the cinema – at the very least, it would make Matt Damon happy.

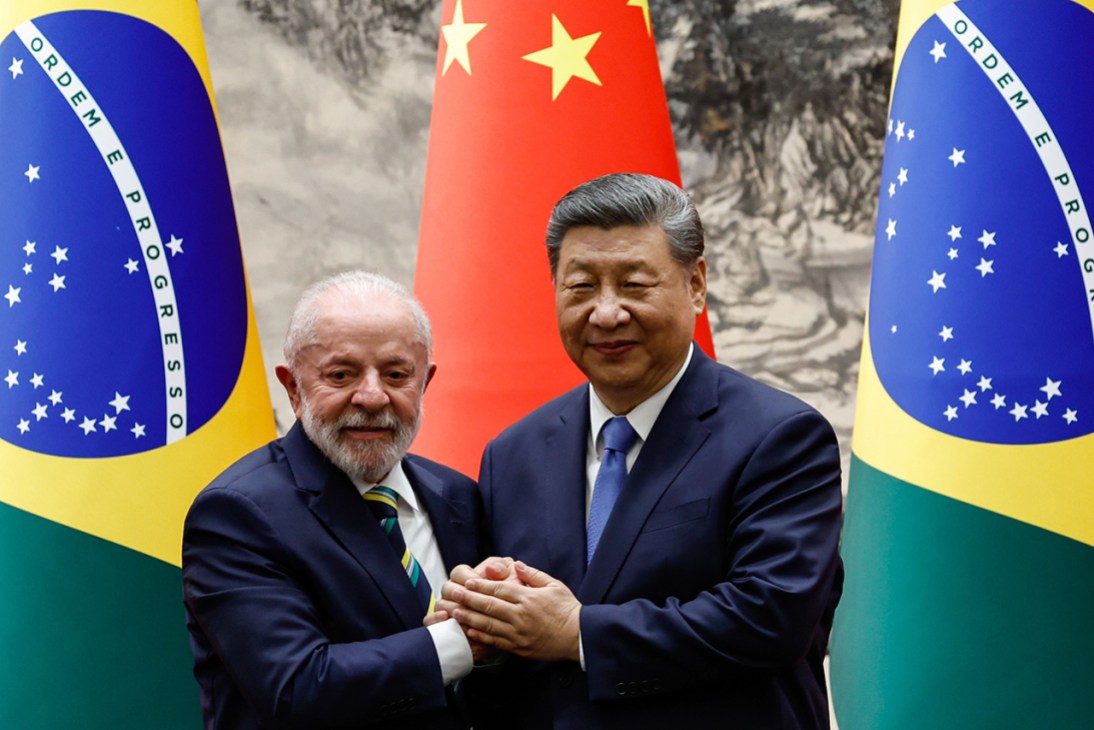

When Donald Trump threatened to impose a 50 per cent tariff on Brazilian goods last week, the reaction in Brasília was swift and vocal (writes Bryan Harris). This economic sanction had little financial motivation; rather, as the US president made clear, the proposed punishment was a rebuke of the ongoing trial of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, who is accused of leading a coup attempt. Scores of politicians lined up to criticise the US administration for impinging Brazil’s sovereignty and putting the interests of one man above those of a nation. The choral reaction, in cities from Belo Horizonte to Belém, was in stark contrast to the markedly hushed responses of Tokyo and Seoul to recent US tariff threats. In South America, the longer-term fallout is likely to be more profound.

Washington has lost its footing on the continent just as Beijing has been deepening its diplomatic and economic relations here. China is now South America’s largest trading partner and second only to the US in Latin America as a whole. As the White House continues to alienate nations in the region with its approach to immigration, organised crime and tariffs, Beijing has a golden opportunity to push Washington out of what it naively calls its “backyard”.

China clearly recognises the moment. In late May, Xi Jinping hosted high-level delegations from dozens of Latin American and Caribbean nations. Along with a good dose of pomp and pageantry, the Chinese leader amped up the rhetoric, highlighting how all of those assembled – himself included – were “important members of the Global South”. These were not just lofty words. Beijing also announced a new €7.7bn credit line and fresh infrastructure investment plans. Days later, it initiated visa-free travel to China for citizens of Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Uruguay. And if there was ever a question of the effectiveness of this charm offensive, it was quickly answered by Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. “China deserves to be looked at with more affection and no prejudice,” he said.

China’s focus has primarily been on fuelling its own domestic growth by ensuring a steady supply of natural resources and raw materials – including oil, iron ore, copper, lithium and agricultural products – through co-operation with this region. But with a population of more than 650 million people, Latin America is also an attractive market for Chinese goods, especially technology and cars.

The greater game at play, however, is geopolitical. China is seeking to counterbalance US hegemony in the western hemisphere. The clearest example of this is Beijing’s growing control over some of Latin America’s largest ports: it is believed that it has built or operates 31 of them in the region. The fear in Washington is that Beijing could use these ports to disrupt US trade, shipping and logistics in the event of a conflict.

Washington has sharply intensified its rhetoric in the past six months. In February the White House practically forced Panama’s exit from China’s flagship infrastructural Belt and Road Initiative. It also hinted at trade repercussions against Colombia if it joined the scheme (which it later did). The US’s strongman posture, however, has only served to alienate political leaders. Colombia’s president, Gustavo Petro, has already engaged in heated exchanges with the White House. And in Brazil, Lula continues to show no intention of backing down in the face of Trump’s threats. In response to the 50 per cent tariffs, he said, “Brazil will not accept any form of tutelage.” Chinese businesses and the country’s government know the art of the deal here. When will the US learn?

Harris is a regular Monocle contributor. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

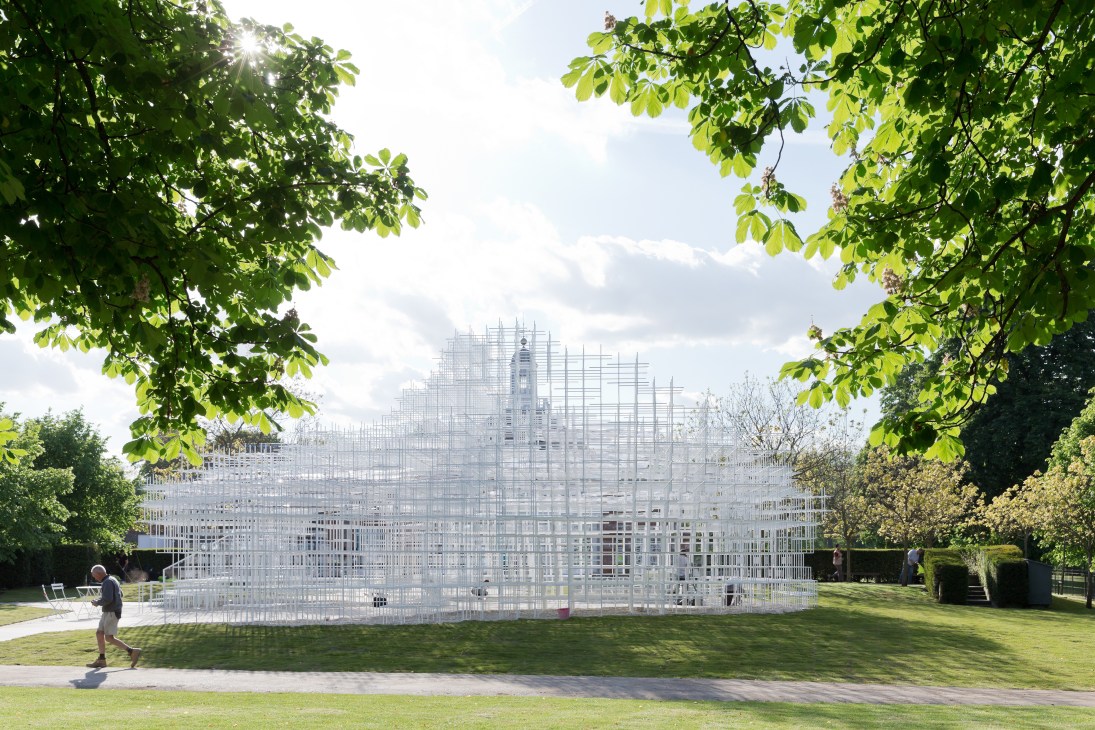

The Mori Art Museum is no stranger to crowd-pulling exhibitions, yet this week’s preview of The Architecture of Sou Fujimoto: Primordial Future Forest drew a particularly eager audience. Industry media, foreign journalists and national newspapers were among those packed into the auditorium to listen to the Hokkaido-born architect, whose work at Expo 2025 has further cemented his reputation as the future of Japanese architecture.

The exhibition, which is open through 9 November, is the first major survey of Fujimoto’s work. At its core lies the concept of the forest. Growing up amid the nature of Higashikagura, a town in central Hokkaido, the architect shared recollections of playing in the woods behind his childhood home. “There was a sense of security, a feeling of being enveloped by the forest,” he says. “Yet it wasn’t closed off; it was always open with a sense of freedom.” As Fujimoto entered the field of architecture, he saw an unexpected, quiet connection between forests and cities – a coexistence of diverse elements and a “loose order amid the confusion.” This idea of the forest became central to his practice, serving as both inspiration and a model for the future of architecture and society.

These ideas present themselves throughout the exhibition, which welcomes visitors with a densely packed room of architectural models spanning more than 100 projects across three decades. The display highlights the open boundaries, amorphous nature and myriad parts that are central to Fujimoto’s architecture. Landmark projects, including his award-winning proposal for the Aomori Museum of Art design competition (2000), House N (2008) and his Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (2013), share the limelight with unrealised ideas and recent endeavours such as high schools, skyscrapers and seagoing vessels. Detailed scale models are showcased alongside studies in foam, paper and concrete, as well as more abstract explorations using objects such as clothes pegs and potato chips. Collectively, the pieces possess a powerful magnetism that invites viewers to slow down and take a closer look. For every camera-wielding visitor, there was someone examining Fujimoto’s delicate handiwork up close – tracing the evolution of a museum concept or eyeing a dream residence.

In a room dedicated to Expo 2025’s Grand Ring, an equally forensic approach has been applied. Despite the immense scale of the structure – the world’s largest wooden architectural work – Fujimoto sees it as symbolic of his approach to ever-larger projects. “The ring transcends architectural scale but, at the same time, the columns are at 3.6-metre intervals and the space beneath [the ring] is open, so it feels very human-scale,” he says. “I’m fascinated by architecture of such significance because it broadens the range of ideas to be applied, from small, human-scale concepts up to large-scale architecture and urban contexts.”

Developed by Fujimoto in collaboration with Keio University professor and data scientist Hiroaki Miyata, the exhibition also unveils “Resonant City 2025”, which presents a vision for a city shaped by enhanced mobility, energy generation and digital technology. It’s a bold proposal with references to a forest-like ecosystem that, alongside the various interpretations of Fujimoto’s work, is already fuelling discussion about how architecture shapes our world, past, present and future.

My Zürich apartment building is a solid Swiss 1960s affair that has the odd twist of Japan (landscaping and terraces) and maybe a bit of Palm Springs (angular modernism and plenty of concrete). This August will mark five years of living under its gravel roof and on a sunny day like today, with the boats crisscrossing the lake, the meadows in the distance and snowy peaks beyond, I feel very lucky. Indeed, it’s something that I never take for granted. I marvel at the view and overall set-up every day that I’m here.

In these warmer months, I also have enormous respect for the architects of the period who put a lot of thought into shade and cross-ventilation to keep residential structures cool. My building didn’t come with a user’s guide for dealing with days over 30C but I’ve enjoyed figuring out how to keep it pleasant on even the hottest days in the heart of Europe. As air conditioning is not a thing here (for now), it takes a bit of planning to know when to adjust the shutters, roll down the blinds, roll them back up, keep some windows closed, others open and when it’s just the right moment to harness a cooling cross breeze. I’d say that 90 per cent of the time I manage to get it right. But on my return from Lisbon last week, a late arrival and too little time for the necessary adjustments meant that an uncomfortable night was compounded by a humid lid hanging over the city and the lack of even the gentlest breath of wind.

A couple of days ago, some new adjustments were made to the shutters – a daytime blackout strategy was put into action. With the overall effect somewhat limited, it was decided that the blackout should be lifted and I set about rolling up the shutters (manually, I might add) and letting the light back in. Or almost. While some shutters were a bit creaky and uncooperative, all went back into place save for one stretch across the front of the apartment. For whatever reason, this roller shutter was particularly grumpy and didn’t want to glide back into its perfectly engineered pocket. It was clearly enjoying the sun, the view and the freedom of being stretched out rather than cramped up. Before long it was a three-person operation but despite much cranking, jiggling and tugging – it wouldn’t budge. What to do? As it was almost dinnertime, we decided to enjoy the dipping sun and the bottle of local white that had been opened. “I think this is one for the morning,” I announced. “We’ll call the manufacturer and get them to fix it.”

On the lower part of the frame I found the name of the manufacturer and snapped a photo. How was this going to play out tomorrow? Would they say that the system was out of production and no longer worthy of a call-out, or that they were already summer break? Or would they spring into action to mend their damaged product? As I was thinking through these scenarios, I was reminded of a conversation that I had with Switzerland’s former ambassador to the US on the topic of installing, maintaining and repairing everything from air conditioners to jet engines and roller shutters. “This is where there’s an acute shortage of skilled labour and it’s going to be these jobs that will not be touched by AI,” he explained. “There’s too much focus on consulting and big tech and not enough on the people who will need to build the infrastructure to house and support these businesses.” I stared at the jammed shutter and thought about all the other window systems that must be out of commission and in need of semi-urgent attention – particularly in the summer months.

Rather than waiting for the company to show up, what if there was a round-the-clock service of highly trained, exquisitely turned-out handy boys who could come round and deal with the problem? In a world where changing a light bulb is too complex or seen as dangerous by many, could this be an idea worth pursuing? A new corps of highly paid, well-respected tradespeople responsible for making the world go round? A recent article in a Canadian daily underlined why there’s money to be made in addressing this hands-on skills gap. Canada has big infrastructure and housing ambitions (like so many other countries) but with an acute shortage of teachers in trade schools, there is little hope of pulling these projects off with home-trained talent. We need a fresh approach to not only creating a new class of educators but also a climate where these necessary skills are recognised as a fast track to rewarding, AI-proof six-figure careers.

Fancy spending some time on the shores of Lake Zürich this summer? Our handy City Guide has everything that you need to know.

The past few years have seen a surge in wellness-seeking early risers jumping out of bed before the cock crows for pre-work runs and yoga classes. LinkedIn is awash with self-congratulatory posts about 04.00 starts, and the quest to be more productive has ushered in a wave of pre-dawn routines in C-suites around the world.

When Sydneysider Ivan Power – an investor, government adviser and morning person – noticed this trend earlier this year, he teamed up with Melbourne-based academic Dr Anna Edwards to launch a study of the “morning economy”. A self-proclaimed “data nerd”, Edwards has been studying the night-time economy since 2009, initially in her native UK and subsequently in her adopted home of Australia. With several research projects and reports underway, the expert already believes that the opportunities for businesses during the ungodly hours could be just as big as they are at the end of the day.

Monocle spoke to Power and Edwards about wake-up routines down under, Australia’s ownership of breakfast and city halls’ rising investment in the 24-hour economy.

Before we dive in, let’s have a quick temperature check. Who saw the sunrise this morning?

Anna Edwards: Not so much; I was out late last night. That’s the thing – sometimes we want to be out late and have a drink after work, and sometimes we want to get up early and enjoy the morning.

Ivan Power: I’m an early riser. Generally, I’m up at about 05.00 and I’m down at the beach by 05.30, either for a swim, a paddle, a surf or to go to the gym. I’m fortunate enough to live in Bronte, a Sydney suburb that’s home to one of the world’s great urban beaches.

What tipped you off that early-morning activity might be more than just a lifestyle trend, and something worth studying?

I: Since the coronavirus pandemic, I began to notice more people in the mornings while doing my laps. But one day, when I was sitting out in Bronte at 06.30, I noticed that there were no seats available at the seven cafes that line the strip. It dawned on me that this increase in business was an economic thing. I posted a few thoughts about the “morning economy” online, and Anna was one of the first people to reach out and express interest in the topic.

A: I was involved in the first-ever measurement of the night-time economy in the UK, so when I read Ivan’s morning economy piece, I saw a huge opportunity. The early-morning hours provide another time frame for us to utilise outside of the regular nine-to-five workday, which is really beneficial to society. One of the projects that I’m working on now is a global comparison of morning activity, which will be available later this year.

Why should mornings matter to city hall?

A: One of the main reasons that cities around the world are investing in their nightlife offerings is to enhance livability and attract talent and investment. But things are changing. People are drinking less alcohol and we’re seeing a shift in what the younger generation is looking for. It’s all about personal choice and providing opportunities for the sky larks, not just the night owls.

How does it compare to when you started work on the night-time economy?

A: When I first started measuring the night-time economy, nobody had heard of it. I remember talking to friends and they thought that it was all about alcohol, which is not true. It’s about making cities in the evening more vibrant and safer by offering a diverse range of activities for a broader audience of people. We need to apply the same kind of thinking to the morning economy. It’s an untapped part of the day, and from a livability perspective, there are opportunities all around the world for cities to embrace.

What data are you collecting?

A: Trading hours, credit card spending, foot-traffic data – things like that. At first glance, I’m seeing more activity in the warmer months, as you’d expect – but also that Wednesdays and Thursdays seem to be the days when we see the most movement. That could be because people tend to go to the office during the middle of the week.

Does the size of a morning economy depend on culture or climate?

A: Moving from the UK to Australia, I learned that it’s fair enough to invite people to a 07.00 park run. That’s not an anti-social thing to do here. Likewise, there are a lot of Asian countries where the early morning is the only time to be outdoors to avoid the heat. There’s a lot that we can learn based on climate and temperature.

I: Australia can get quite hot, and as a country, we’ve put a lot of thought into our breakfasts – they have to be done really well. In fact, we’ve even exported a little bit of that breakfast culture to the rest of the world.

It’s winter in Australia right now. Does it get lonely in the early hours?

I: It’s not lonely at all, and the number of active people stays fairly consistent. Sure, it’s not as busy in the depths of winter as it is in the height of summer. But there are still plenty of people taking the time to get out in the mornings – to look at the water, walk along the coastal path and watch the sun come up. This is the way that certain cohorts want to socialise, and it’s been quite a development over the past decade.

Is the dawn crowd spending money? Or just stretching?

I: Although I didn’t pay for my gym membership at 05.30, I’m using it at that time and morning people are spending a lot of money on leisure wear and other accessories. Beyond food and drink, there are parts of the morning economy, such as workout classes and clothing, that we are amortising in those early hours.

Is public safety a big challenge?

A: Yes, but not a huge issue. Mornings are a safer option than the evenings because coffee shops and gyms don’t have the same challenges with alcohol-related anti-social behaviour. But during the winter months, we must think about public lighting, transport and having sufficient traffic at certain places to make people feel safer.

Anna, you’ve spent 15 years studying night-time economies and watched cities invest billions in after-dark programming. Now you’re telling them to invest in sunrise too. Are cities spreading themselves too thin, or is this genuinely the future of urban economics?

A: We’ve seen a seismic shift in the way that the night-time economy operates around the world. What was treated as a problem that needed to be suppressed through regulation is now actively supported. There are approximately 80 cities globally with dedicated night-time economy governance, and a broader range of people are socialising at the end of the day. But I should also mention that, right across the world, we’re seeing a shift away from the evening towards an all-day economy. Here in Australia, New South Wales has a 24-hour economy commissioner with a 60-person team.

What might a future-fit, fully awake city look like?

A: Back in the day, shops were open from nine to five, Monday to Friday, because women, who typically stayed home during the week, could go out and do the shopping. But as they entered the workforce, opening hours extended through weekends and evenings to allow people to shop after work. The coronavirus pandemic has shifted things again, which has provided us with an opportunity to think about the way that we use our time and how we can introduce more flexibility. It’s not about replacing the night-time economy. It’s about finding opportunities for businesses in the morning too.

Japan Cuts, North America’s largest festival of contemporary Japanese cinema, kicked off on 10 July at Japan Society in Manhattan. With screenings of 30 films over 11 days, the festival – now in its 18th year – includes premieres, documentaries and restored classics. There will also be a special award for the director and screenwriter Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and a closing reception with traditionally distilled shochu imported for the occasion. Japan Society was founded as a non-profit organisation in 1907 and is today housed in a 1971 building designed by the much-admired architect Junzo Yoshimura. Monocle spoke to Japan Society’s director of film, Peter Tatara.

What is the festival’s theme, and how do you make your selection?

Japan Cuts is dedicated to showcasing contemporary Japanese cinema. Each year, the festival offers New York audiences a snapshot of works produced in Japan over the past 12 months – from major blockbusters, indie flicks and documentaries to shorts and experimental works. This year, we’re proud to celebrate the acclaimed director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. He will receive the Cut Above Award, which recognises his lifetime achievements, and we will be hosting the New York premiere of his new release, Cloud, as well as a screening of his recent remake of Serpent’s Path. The selection process takes approximately six months, beginning at the Tokyo International Film Festival, where we spend about 10 days meeting with Japanese film-makers and distributors. To arrive at our final list of 30 films, the team reviews more than 300 works and engages in discussions before deciding on the final selection.

What are some of the highlights?

We are thrilled to welcome Yuumi Kawai, who recently won the best actress award at this year’s Japan Academy Film Prize for her performance in A Girl Named Ann. We’ll be hosting its North American premiere, along with a screening of She Taught Me Serendipity. Further highlights include the first New York screening of A Samurai in Time, which won best film at the Japan Academy Film Prize, and Teki Cometh, which took home the grand prix for best film, as well as awards for best director and best actor at the Tokyo International Film Festival. We’re also excited to spotlight some smaller projects, and our Next Generation section will showcase works from emerging independent directors.

Tell us more about the award to Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

Every year we present a Cut Above Award, which is given to a director or actor in celebration of their contributions to cinema. Previous winners include Yuya Yagira, Joe Odagiri, Kirin Kiki, Koji Yakusho, Shinya Tsukamoto, Sakura Ando and Lily Franky. This year, we’re honoured to present it to Mr Kurosawa, recognising both his works as well as his lifelong commitment to film-making.

And restored classics too?

Every year Japan Cuts features a small selection of classic cinema, focusing on new restorations or anniversaries. With Mr Kurosawa in attendance, we’ll be showing a remastered edition of the original Serpent’s Path from 1998, and a 35mm screening of his License to Live. We’ll also be celebrating the 30th anniversary of Shunji Iwai’s feature debut, Love Letter, with the North American premiere of its 4K restoration.

The closing film sounds interesting – give us a synopsis. Can the audience expect a glass of ‘shochu’?

This is one of my favourite films of the festival. We’re closing this year’s edition with the international premiere of The Spirit of Japan. It’s a beautiful documentary about the Yamatozakura distillery in Kagoshima prefecture – one of the last handmade sweet-potato shochu distilleries in Japan. The film follows fifth-generation master brewer Tekkan Wakamatsu as he carries on 175-year-old traditions passed down by his father, Kazunari Wakamatsu. The documentary gives you a behind-the-scenes look at the shochu-making process, but it offers more than that. It’s a deeply moving portrait of a father and son and an observation of vanishing traditions. We’re honoured to share this film and excited to have director Joseph Overbey and producer Stephen Lyman – and even Tekkan Wakamatsu himself – in attendance for a Q&A. After the screening, the audience can enjoy a reception with Yamatozakura shochu, imported just for this event.

Tell us how you became interested in Japanese cinema. Any favourite films and directors?

I’ve had an interest since I was a child. I grew up in a small town and finding Japanese films on VHS was a window to another world. It made me want to learn more about the culture, the food, the language and eventually inspired me to travel to Japan – cinema is a powerful ambassador to the world. I am drawn to directors such as Kurosawa and Ozu, as well as Fukasaku. Fumihiko Sori’s Ping Pong is also one of my absolute favourites.

Which features would you recommend for novice Japanese film watchers?

If this is your first time attending Japan Cuts, beyond the major titles, I would recommend My Sunshine, a beautiful piece about teenage adolescence; the comedy Kaiju Guy!; the outlandish The Gesuidouz; and So Beautiful, Wonderful and Lovely, featured in this year’s Next Generation section. Together, they give a comprehensive introduction to Japanese cinema.

Japan Cuts runs until 20 July, at Japan Society 333 E 47th Street, New York.