The Islamic Republic of Iran, founded in 1979, was created in the image of its inaugural Supreme Leader: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the fundamentalist firebreather who encouraged his acolytes to seize the US Embassy in Tehran, offered to underwrite the murder of a British novelist and ordered hundreds of thousands of his country’s young citizens to pointless deaths in a war against Iran’s neighbour, Iraq.

It is arguable, however, that the crucial figure in the history of the Islamic Republic was Khomeini’s successor, the cooler and cleverer Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has been reported dead in US-Israeli strikes, aged 86. Iran’s power politics flourished on his watch, at least for a while, taking advantage of the Middle East’s chronic chaos to assert itself as the dominant regional power – albeit one which had no friends or allies, merely clients and vassals.

Ali Khamenei was born in Mashhad on 17 July 1939. He was set on his path early, enrolled in Islamic schools from the age of four. By his early twenties, Khamenei was studying in the Islamic seminary at Qom, one of the most prestigious – and one of the least compromising – centres of learning for up-and-coming Shia clergy. Among Khamenei’s teachers was a charismatic agitator with firm views regarding Iran’s then-leader, the repressive – and US-backed – Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The name of Khamenei’s early and lifelong mentor was Ruhollah Khomeini.

When the Shah wearied of Khomeini’s fulminating and drove the turbulent priest into exile in 1963, Khamenei remained in Iran. He paid a price for his enduring loyalty to the older cleric: he was arrested and tortured, spent three years in prison and another three in internal exile. When Khomeini returned to Iran to lead his revolution in 1979, Khamenei was welcomed into the inner circle. This was no guarantee of safety: an assassination attempt in June 1981, attributed to the eccentric militant organisation Mojahedin-e-Khalq, cost Khamenei the use of his right arm; he was elected president four months later while still recuperating. When Khomeini died in 1989, Khamenei was the obvious choice as the Islamic Republic’s second Supreme Leader.

Khamenei’s most impressive accomplishment might have been preserving his role as long as he did. Pro-democracy protests in 2003 and 2009, some of them bloodily suppressed, did not untowardly wobble him and nor did the upheaval of the Arab Spring from 2011 onwards. Indeed, Iran seized the opportunity presented by the latter tumult, becoming a significant – if not the significant – power broker in five Arab centres: Beirut, Sana’a, Gaza, Damascus and Baghdad.

Domestically it was difficult to acclaim Khamenei’s rule a success. Iran was economically hobbled by bureaucracy and corruption, and by sanctions imposed to thwart the country’s ambiguous nuclear ambitions. Iran, a potential powerhouse, stayed needlessly poor. Khamenei’s unbending interpretation of Islam saw Iran remain a country in which, well into the 21st century, gay men were hanged for being gay men, and women were assaulted by employees of the state for failing to adhere to a dress code.

And yet despite setbacks Khamenei’s forbidding visage continued to glower, apparently inextinguishably, from posters overhanging Iran’s public spaces. In 2020 the architect of Iran’s regional machinations, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Major General Qassem Soleimani, was killed by a US drone strike. Other IRGC officers and Iranian nuclear scientists met picturesque demises, either overtly or covertly, at the hands of Israel. There were further mass protests against Khamenei’s rule in 2022, occasioned by the death of a young Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini in the custody of the goons ordered by Khamenei to punish immodest flashes of female hair.

It began to unravel for Khamenei on 7 October 2023. The Palestinian militant group Hamas, long supported by Iran, broke from the confines of the Gaza Strip and killed more than 1,200 people. Israel’s response was not confined to Gaza, or to Hamas. Israel hit Iran’s proxies Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen and targets associated with the regime in Syria, where Iran had propped up former president Bashar al-Assad through the Arab Spring and beyond.

By June 2025, Hamas was destroyed, Hezbollah decapitated, the Houthis diminished and Assad defenestrated. Israel, with the assistance of the US, came for Iran directly, bombing nuclear and other sites. Iran was unable to muster much response beyond ineffectual rockets and blundering drones. Iran’s people sensed weakness, rose again – and were, again, put brutally down. Thousands were killed.

Towards the end, as the US and Israel prepared a decisive strike against him, Khamenei found himself in the impossible position of being a stubborn old man ruling an impatient young people. He probably understood, and just as likely did not care, that his ossified theocracy could not have survived compromise or engagement with the modern world. It is altogether unknowable whether he derived much satisfaction from embracing the martyrdom to which he urged – and condemned – so many others.

1.

We start this Sunday with a thank you to all those readers who took the time to drop a few encouraging words of support and additional ideas off the back of last week’s column. In case you missed it, you can read all about my take on continuing education and the importance of doing a stint in the military or hospitality here. If you’re still in a state of confusion and despair, then might I suggest you enrol your son or daughter in the SFS? While it might sound like an elite, heavily armed sibling of the UK’s SAS or SBS, this SFS is a far more rigorous and perhaps essential institution in today’s challenged workplaces. Officially launched at the Kulm Country Club in St Moritz several weeks ago, Sagra’s Finishing School (SFS) is designed with a clear and simple mission – to ensure your offspring have qualifications in a manual service such as plumbing, upholstery or carpentry, or help them become a master in a craft like hand embroidery or dog manicures.

Based in London with roots in Galicia, SFS encourages both parents and children to recognise that a degree from Princeton or McGill is something to be rightly proud of but, when entire business strategies and court arguments can be cranked out by one of Anthropic’s services, there is an urgent need for a plan B that involves rolling up sleeves, dirtying hands and delivering a product or service for which consumers will increasingly pay luxury margins. If you’d like an introduction to the SFS, drop a note to info@monocle.com.

2.

Speaking of initialisms, I have three more for you that defined my past week in the UAE.

NPO (Nissan Patrol Office). This is what you get when you cross four Monocle staffers with a busy schedule, a hundred kilos of print and a fresh-off-the-lot 2026 Nissan Patrol. Laptops and smartphones might be essential tools for daily business but when you need to make calls, turn up looking sharp and stay secure on the Sheikh Zayed Road, there’s nothing better than a solid set of wheels. Having a driver with an eye for Gulf modernism also helps.

PDR (private dining room). Standard in so many corners of the world but still so rare in corners of Europe and the Americas. Just as restaurants need to have enough emergency exits and accessible bathrooms, there should be a code demanding that all proper establishments have PDRs for emergency summits with Australian clients who demand special previews of large-format printed work at the end of an evening.

MMM (Martin’s Midnight Majlis). This is a new organisational tool that we employed all last week while in the UAE. It involved six colleagues assembled for nightcaps led by Martin, who ran down the diary for the next day and ensured that there were enough NPOs for people to get from Abu Dhabi to Dubai and PDRs for top-secret meetings.

3.

And no, I’m not stuck in the UAE. Thankfully the NPO got all of us to the airport before things kicked off in the Gulf and I’m tapping out this column under a very sunny Lisbon sky. That said, closed airspace has prevented one colleague from getting back from Tokyo but she’s found some more business in Hong Kong and, of course, we’ll have full coverage of the conflict on Monocle on Sunday, live at 10.00 CET. Finally, if you happen to be in Taipei this coming Thursday, drop us a note and we’ll send you an invite to a little cocktail reception that we’re hosting for our loyal Taiwanese readers and anyone who happens to be in town. I look forward to seeing you then.

Enjoying life in ‘The Faster Lane’? Click here to browse all of Tyler’s past columns.

This fast-changing news event continues to evolve and we will provide updates as new information becomes available. The article was last updated on 28 February at 14.00 (GMT).

It is the kind of decision which would normally be announced in a solemn address from the White House, clearing the prime-time schedules of major broadcasters. Instead, at around 02:30 US east coast time, President Donald Trump cried havoc and let slip the dogs of war with a video posted on his own social media platform, Truth Social. Tieless, sporting a white “USA” cap and standing behind a lectern erected in an indeterminate location, Trump spent eight minutes making some extremely vague arguments in favour of a very large gamble.

Trump declared that the US had launched “major combat operations” against Iran because of “imminent threats from the Iranian regime”. He did not offer any hints as to what these were. For Israel, whose forces have joined the attack, it is – as it has always been – less ambiguous. Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, focused on Iran’s nuclear programme, which Israel has always regarded as an existential menace. Whether one likes a given Israeli government or not, it should be possible to understand why Israelis generally don’t extend much benefit of the doubt to people calling for their extermination.

As for the excellent question “why now?” the answer might be, as the US and Israel see it, “why not”? The Islamic Republic is weaker than at any point since the revolution of 1979. At home, Iran’s economy is languishing, its people furious; nobody knows how many demonstrators were killed by the regime in the most recent wave of protests but all estimates run into the many thousands. Abroad, Iran’s proxies across the Middle East have been destroyed, decapitated or disoriented by Israel’s settling of accounts since 7 October 2023. If Tehran picks up the phone now to Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen or the various brigades it sponsors in Syria and Iraq, there might not be an answer.

Atop all of which, last June’s 12-day campaign of air strikes by the US and Israel against Iran demonstrated that Tehran could neither defend its airspace nor muster much by way of retaliation. The initial scattershot of retaliatory strikes that Iran has made against targets in Israel, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Iraq and the United Arab Emirates look very much of the “use them before we lose them” variety.

This decision by Trump might seem difficult to reconcile with his long-held disdain for foreign entanglements (social media archaeologists are gleefully disinterring old Trump posts in which he accuses former president Barack Obama of spoiling for a fight with Iran as a distraction from his own incompetence). But it also might not be. If there is a Trump Doctrine discernible in the foreign policy of his second term, it is a belief in short, sharp shocks, on the assumption that the results, unforeseeable though they always are in war, will be an improvement on the status quo. In Trump’s first year back in office, US forces were sent to kidnap Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, an American drone and missile blitz was launched against Islamist militants in Nigeria, and further strikes were made on similar groups in Syria, Yemen and Somalia. There was little follow-up, either because Trump believes he has made his point or has lost interest.

The attack on Iran might fit into this framework. Nobody, at least as of this writing, is suggesting that the 1st Marine Division march to Tehran and drape the Azadi Tower in red, white and blue. As it stands, Operation Epic Fury, as the US is calling it, is not inconsistent with isolationist indifference. Speaking recently to Monocle Radio’s The Foreign Desk, Trump’s former national security adviser John Bolton, reflecting on the nation-building hubris surrounding the 2003 invasion of Iraq – for which Bolton was an avid cheerleader – said: “My view back in Iraq was that we should give them a copy of The Federalist Papers and say ‘Good luck’. We’re not good at nation-building.”

Trump’s statement suggests that he believes he is creating the opportunity for Iran’s people to liberate themselves. “When we are finished,” he said of the US action, “take over your government. It will be yours to take.” He further urged “now is the time to seize control of your destiny and to unleash the prosperous and glorious future that is close within your reach.”

It’s a fine idea, and no less than Iran’s people have long deserved. But the list of wars that have panned out as their instigators intended is short, and the list of people marooned in the gulf between Trumpian sensationalism and reality is rather longer.

For further updates from the region, tune in to ‘Monocle on Sunday’ and ‘The Globalist’ on Monocle Radio.

I don’t want to embarrass the gentlemen, so will obfuscate on the exact location of our rendezvous. The person in question is a senior diplomat, a British one, in a part of the world that invests heavily in all manner of things, including design and architecture. In short, it’s a place that believes that, sorry, appearances do matter.

Our diplomat is no doubt a very clever man but, well, he looks like he shares a wardrobe with Boris Johnson. On the day I visited him, his pointy shoes needed a polish. He had also clearly been forced to partake in too many banquets of late. His suit jacket looked rather taut and the bottoms of his trousers had kissed goodbye to his ankles (and not in a hipster way). I know, that’s not very kind of me but he is out in the world selling an image of our nation and supposedly doing his best to boost British trade.

As I listened to him talk, I wondered what packing instructions the Foreign Office gives to the men and women heading off to represent the UK. You would hope that they suggest purchasing some smart, made-in-Britain shoes from, say Crockett & Jones, and a suit that looks the part. If they can’t stretch to Jermyn Street, at least something new from Marks & Spencer.

I have always been wary of people who say things such as “I’m not interested in fashion,” or “I don’t care what it looks like, as long as it works.” These same people tend to be dismissive of art and architecture, indeed any touchpoint where the mundane can be elevated, where small moments of considered beauty can transform a person’s day, even impact health and educational outcomes. And the trouble is, perhaps like our diplomat, they miss the bigger picture. Something that functions well and looks the part is often good for commerce too – and certainly good for a nation promoting its soft-power assets.

On Wednesday, Monocle co-hosted an event at the Hungarian embassy in London. It was to mark the publication of Hungary Today, a book that Monocle has produced in partnership with Visit Hungary to promote tourism in the country. It’s a thing of beauty. Shot by a single photographer, Julia Sellmann (she also shot our Expo on the Castellers – the Catalans who build human towers – in issue 179), it has a consistency of tone and colour that is very pleasing. There’s also a unique binding process at play. The design by our art director, Sam Brogan, is flawless. It was edited by Steve Pill, who guides many of these partnership programmes. But what’s also special is that we found a tourism organisation with ambition, one that wanted to make something that told their country’s story afresh.

The evening’s main host was the Hungarian ambassador to the UK, Ferenc Kumin. He has a nice suit, he’s charming and knows how to promote his nation. We did a fun interview midway through the evening, where he explained the wines that were being served, told people where he likes to spend his Hungarian summers (he’s a north Lake Balaton kind of guy), and unpacked the musical and engineering educations that have helped his country excel in both fields.

And the embassy is good too. More than a century ago the building was an outpost for the Austro-Hungarian Empire but after they parted ways the Austrians moved around the corner and the Hungarians kept this property on Eaton Place. It remained the embassy during the communist era and today, in a rather pristine state, continues its work of keeping Hungary on the diplomatic map and looking tight.

For the April issue of Monocle, our foreign editor, Alexis Self, who came to the bash too, has been working on a special feature about the modern embassy. So you can expect to read much more on this topic soon. We have even persuaded the British ambassador to Somalia to pen a piece. Well, he is married to Konfekt’s editor, Sophie Grove, so we had an in.

But in the meantime perhaps we all need to channel our inner ambassador of a morning, think about how we are going to tell our stories – and our company’s as well – as we step out of our front door. Appearances matter. Shoes too.

To read more columns by Andrew Tuck, click here.

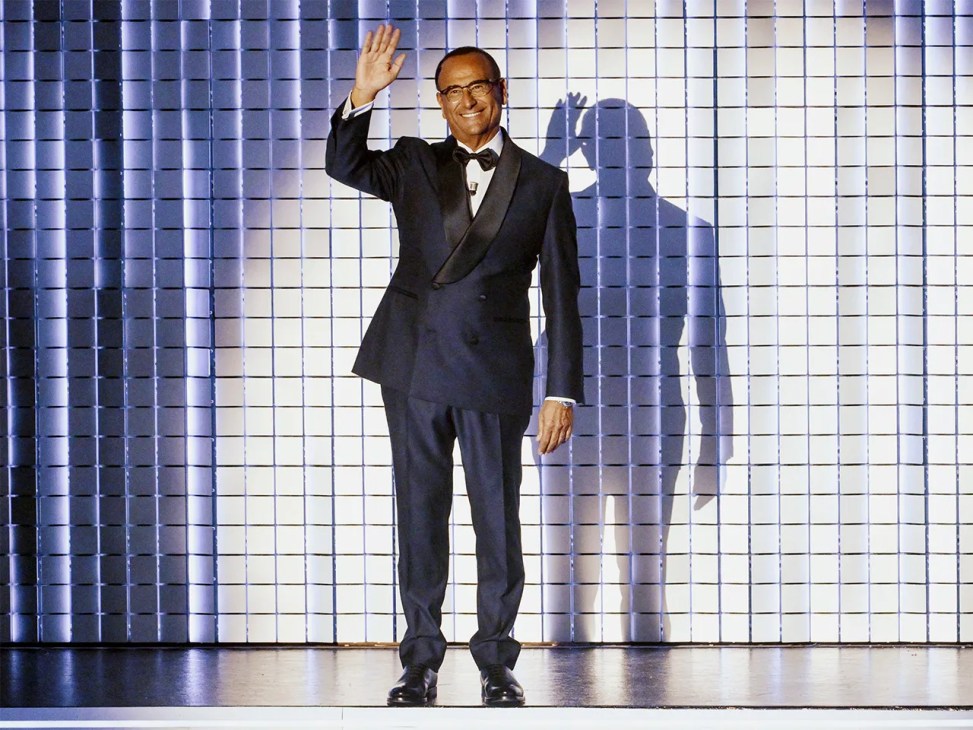

One Italian newspaper calls it Italy’s Super Bowl. A more accurate description for Sanremo Music Festival might be a cross between Eurovision and New York’s Met Gala – albeit a more insular version. Regardless, Italians are glued to their screens for five days each February as they watch musicians most of the world has never heard of competing to be crowned king or queen on the song contest’s final night, which takes place tomorrow.

This glitzy, establishment event held in the Teatro Ariston in coastal Liguria is set-piece Italia: a reassuring mainstay that helps viewers beat the last of the winter blues with spring on the doorstep. Now in its 76th edition and broadcast on the Rai state network from 20.40 until well after 01.00, the media furiously unpicks the previous night’s shenanigans (including, this year, a bizarre attempt to use AI that saw audience members briefly turned into yellow ducks). But beyond new gimmicks, ratings (or “lo share” in Italian) are what matter most to the network.

And yet this year has been blander and more boring than ever. Everything about the programming is nostalgic and retrograde, from the graphics to the songs themselves. Il Foglio newspaper has called the song competition representative of a “calm and melancholy Italy” with “songs that seem to be written in a temporal limbo.” And it’s hard to disagree. Who better to host it, then, than the vanilla, housewives’ favourite Carlo Conti (pictured above) – back for a second year – his perma-tan somehow an even deeper shade of mahogany in 2026.

This is exactly how the government wants the festival to unfold. After rumours circulated that far-right prime minister Giorgia Meloni would attend, she took to social media to rebuff the suggestion. “And I’m sure Sanremo will shine without imaginary guests,” she added. “Because it’s the greatest celebration of Italian music – and there’s no need to force political controversy into it.”

Much as the government might want political controversy to be absent from the show, it rarely is. Meloni’s words were a thinly cloaked attack on previous editions under the artistic direction of Amadeus. He had attempted to shake things up by making the show more diverse and more representative of contemporary Italy. That led to several on-air controversies, including rapper Ghali, who is of Tunisian origin, calling to “stop the genocide” on the 2024 edition, a reference to the war in Gaza. His apparent snubbing at this month’s Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony in Milan (his performance was never given a camera close-up and RAI commentators didn’t name-check him) was seen by some as a reprisal for his Sanremo statement.

The sanitised 2026 edition might be stripped of satire and spice but even vanilla Conti has managed to court a smidgen of controversy. This year he invited comic Andrea Pucci to co-host the third night, seemingly brushing over accusations of stereotypical and homophobic tropes in his jokes. After a backlash, Pucci pulled out – but not before being defended by Meloni, suddenly happy to talk politics. “The illiberal drift of the left in Italy is becoming frightening,” she said.

And that’s as juicy as it gets. From feting celebrity bad boys made good (Achille Lauro) to celebrating family values through the appearance of Olympic-medal winners (speed skater Francesca Lollobrigida got a big round of applause when she mentioned her son), Sanremo has been a snore fest. And it even seems to be affecting “lo share”. This year’s second night had a little over nine million viewers and 59.5 per cent of the viewing audience, compared to 11.8 million people (a 64.6 per cent share) at the same juncture last year. Italians could do with a little more spice.

Ed Stocker is Monocle’s Europe editor at large.

The concentration of US firepower around Iran now looks less like signalling and more like sequencing. For months, tensions between Washington and Tehran have simmered over nuclear thresholds, regional proxies and the careful choreography of red lines repeatedly tested but never quite crossed. What distinguishes this moment is not the rhetoric but the hardware. The assets now in play suggest that the US is no longer merely demonstrating resolve – it’s positioning itself for choice.

Since late January, a carrier strike group built around the USS Abraham Lincoln has been operating in the region – substantial enough on its own. But increasingly, there are more. The USS Gerald R Ford, the largest aircraft carrier in the world, has been positioned at the mouth of the Mediterranean and is moving eastward. Two carrier strike groups – one in the Arabian Sea and one in the Mediterranean – would give Washington overlapping arcs of airpower and cruise-missile reach. Around them sit at least 11 air-defence destroyers, three littoral combat ships and two to three attack submarines equipped with Tomahawk missiles. That is the naval element of the equation: visible, mobile and readied to project force.

The second part is both logistical and defensive. In the past month, more than 250 US military airlift flights have landed in the Middle East and surrounding hubs, moving large equipment and air-defence assets. Over the past two weeks, C-17 Globemasters and C-5 Super Galaxies – the US Air Force’s broad-shouldered, heavy-lifting aircraft – have been shuttling equipment into American facilities across the Gulf. The likely purpose is straightforward: harden bases against retaliation before any strike begins.

At Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, aircraft numbers have climbed from 16 to 29, including seven C-17s and 17 KC-135 refuelling tankers. Unlike those behemoth aircraft carriers, tankers are a more subtle indicator of intent. They extend range, loosen political constraints and allow aircraft to operate from further afield if host nations hesitate.

The final element is geographical. Flight tracking over the past week shows multiple waves of KC-135 tankers moving from the US via the UK to bases in Greece and Bulgaria. Six were tracked on 16 February; another 10 followed on 18 February, staging through the UK before heading southeast. The message is implicit. Even if access to some Middle Eastern bases becomes politically fraught, aircraft could operate from southern Europe, with tankers bridging the distance. The movements of US assets confirm that Washington is deliberately widening its geography.

Overlaying all the traffic and hardware is command and control. Six E-3 Sentry AWACS aircraft – the distinctive radar-domed platforms that map the battlefield in real time – are now in theatre. With sufficient tankers and airborne early warning cover, a large-scale air campaign moves beyond theory and threat.

For now, diplomacy provides the choreography. Warships and aircraft provide the leverage. If Washington were to move beyond signalling, its target set would likely be precise, not expansive.

Where might the US and Iran target if negotiations fail?

The most obvious focus would be Iran’s nuclear infrastructure: enrichment facilities such as Natanz and Fordow, centrifuge assembly workshops, heavy-water production sites and supporting research centres. These are hardened, dispersed and in some cases buried deep underground. A campaign against them would require sustained sorties, bunker-penetrating munitions and careful sequencing rather than a single dramatic strike.

A second tier of targets would sit outside the nuclear file but within Iran’s military architecture. Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) command-and-control nodes, missile depots and drone-production facilities have become central to Tehran’s regional strategy. In recent years, Iran has refined its use of precision-guided missiles and long-range drones via proxy networks stretching from Iraq and Syria to Lebanon and Yemen. Disrupting those supply chains – storage sites, launch platforms and transport corridors – would form part of any broader attack strategy.

Energy infrastructure presents a more politically fraught category. Iran’s oil export terminals, refineries and petrochemical hubs are critical to state revenue but also deeply entangled in global markets. Direct strikes on such facilities would reverberate well beyond the Gulf. Historically, Washington has been cautious about triggering energy shocks that punish allies as much as adversaries.

Tehran’s options in return are asymmetrical but potent. US bases in Iraq, Syria and particularly the Gulf (including Al Udeid in Qatar and naval facilities in Bahrain) sit within range of Iranian ballistic missiles and drones. Maritime traffic through the Strait of Hormuz remains an enduring pressure point; even limited disruption can rattle markets. More plausibly still, Iran could activate allied militias to apply calibrated pressure while maintaining deniability.

A fresh round of US-Iran talks begin today in Geneva, with Oman mediating. The timing is awkward; negotiations are resuming just as the military appears closest to operational readiness. Taken together, the naval mass, reinforced air defences, tanker bridge to Europe and expanded airborne command assets suggest that Washington could sustain a significant campaign. Donald Trump’s administration, perhaps more than others, is capable of tilting leverage toward action. The open question is not capability, it is intent. Hopefully Omani negotiators and a little Swiss hospitality can keep these foes from deadly escalation.

This article was originally published on 24 February 2026 and was updated on 26 February 2026 to reflect the pending talks in Geneva.

Inzamam Rashid is Monocle’s Gulf correspondent. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

The art crowd heads to the US West Coast this week for Frieze Los Angeles (Frieze LA). Since 2019 the fair has been a platform for local galleries as well as a sunny meeting point for international players and collectors, particularly from across the Americas. This edition of the fair kicks off with previews today on Thursday 26 February and runs until Sunday 1 March. Here the director of Americas for Frieze, Christine Messineo, shares the gallery presentations that you can’t afford to miss, how the art market is faring and where to end up for dinner after a day at Frieze LA.

What’s new at Frieze this year?

At the entrance of the fair you’ll see Patrick Martinez’s debut, a powerful neon installation addressing political realities and immigrant rights. It’s a resonant work that extends across the city on billboards and digital screens, connecting the fair to the life of Los Angeles itself.

For the first time in LA we’re also introducing the Frieze Library. This permanent, publicly accessible collection of artist publications marks the reopening of the Pacific Palisades Library following the January 2025 wildfires. This resource preserves the present moment through the lens of the arts community. It’s sure to have a lasting impact.

Which booths are a must-visit for those coming to the fair?

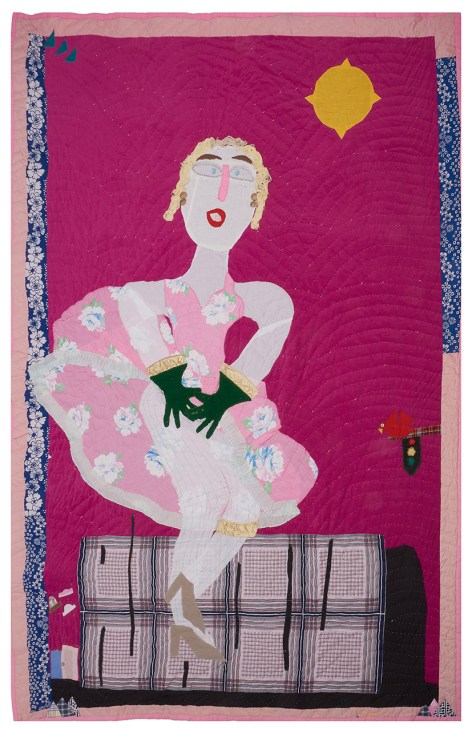

While it’s difficult to narrow down a must-visit, a few standouts include: Betye Saar’s centennial at Roberts Projects offers a powerful reflection on Black identity and political art; Sprüth Magers revisits the enduring influence of John Baldessari; and 303 Gallery presents Alicja Kwade’s investigations into time, value and circulation.

Meanwhile, 86-year-old Yvonne Wells shows figurative quilts referencing Southern identity and iconic figures at Fort Gansevoort. Ortuzar features Linda Stark’s alchemical, feminist paintings and Parker Gallery showcases Marley Freeman’s gestural, textile-inspired canvases.

How is the US market faring so far in 2026? What are you expecting from sales this year?

I’d say there’s been a renewed sense of confidence in the market. In LA in particular we’re seeing new collectors engage – asking questions, spending time with galleries, getting involved. Although last year a more cautious approach was widely reported, all our fairs exceeded expectations, and we are seeing galleries find creative ways to navigate the prevailing conditions.

In LA, for example, galleries such as Château Shatto, Parker, Sebastian Gladstone and Sea View are all growing – or have grown – locally, and the new bicoastal gallery Hoffman Donahue is showing how collaboration can make things more sustainable by marking a new chapter. Emerging galleries are stepping up too, bringing fresh energy, prioritising artist relationships and building community, all of which shows how strong and connected LA’s creative scene is.

The 2025 event arrived at the same time as the devastating fires. How has the art scene fared over the past year? Has the city bounced back?

What continues to define Los Angeles is its vibrant, interconnected community of artists, galleries, curators, institutions and collectors – all showing up for one another. Last year was a testament to this resilience and many are still rebuilding. Through the dedication and support of both local and global audiences, the community has demonstrated remarkable strength. That spirit of care, collaboration and engagement continues to shape LA, reinforcing the transformative role that art and its makers play in our city today.

Where do you recommend for dinner at the end of the day?

Near the fair, I’d recommend the izakaya RVR for a special occasion, Coucou in Venice for a French bistro atmosphere and The Mulberry Los Angeles on Sawtelle for dinner followed by a lively night out.

There’s a change of pace this issue. We’ve put to one side the page architecture that usually shapes the issue and given the entire magazine over to The Monocle 100, a directory of people who we like, places with important stories to share and products that we covet. It’s a list that is hopefully useful but raises some smiles too.

We started working on this project some months ago, asking our team to nominate everything from the best military kit to running shoes, artworks to modernist apartment blocks (and even the ultimate roadside shrubbery). I think that they’ve done a fine job, even if there was some jostling for page acreage among editors keen to allow their selections to shine.

Beyond the competitive fun of pulling this together, there’s another reason why I hope that this issue hits the mark. It is a celebration of talent, shining a light on both established and aspiring names. It’s also a blast of positivity, global know-how and spotting opportunities at a time when such ambition can often be hard to locate in our media – or, indeed, anywhere.

So, you’ll meet a man taking a stance against graffiti vandals scarring his city, discover how Dr Stretch is manipulating a nation back to litheness, see how architecture is helping a city to rediscover its soul after a terror attack, slip into a cosy armchair in the perfect airport lounge and have a go on a vending machine that supports local businesses.

Also commanding some prime glossy-papered real estate in this issue is our annual Property Survey, which is timed to land ahead of Mipim in Cannes, the industry’s largest fair (we will be there again this year with a Monocle Radio studio at Le Palais des Festivals). Over our nicely appointed pages, we visit a new public housing project in Singapore that’s embracing nature, drop in on the agents charged with selling Dubai’s most valuable homes in the city’s highly competitive market and see why developers in Japan are wooing renters with pooches. Poodle power is on the rise. I’m all for it.

While I have you, if you are a subscriber, take a tour around our rapidly expanding collection of digital city guides – Palma and Dubai have just gone live. Written by our editors and correspondents, they are constantly being updated and will help you to unpack a city with ease. Come to think of it, they deserved an entry in The Monocle 100.

There’s another piece of travel news to share too. Always passionate about good hospitality, we have just launched the The Monocle Townhouse at the Widder Hotel in Zürich. This three-bedroom establishment, with an epic roof terrace, sits on the heart of the city and all of its furniture, art and fittings have been selected by us. There’s some rather fine reading material too for guests to peruse.

Finally, there are also upcoming events in the Gulf and Asia. You might have guessed that we like spending time with our readers. In the meantime, if you have thoughts or ideas to share, please always feel free to send me an email at at@monocle.com. Have a great month.

Illustrator Ana Strumpf moved to the Locarno building with her sons having lived in the US for four years. “I needed a neighbourhood that I could walk around,” she says gesturing to the vast window of her airy, art-filled apartment in the 1950s structure. Locarno is one of two identical buildings (the other named Lugano) in São Paulo’s Higienópolis and in is a portal to the past that offers some clues to what makes a meaningful community today.

From her studio in what would originally have been the maid’s bedroom, she says that the appeal of living here is the lively community. Strumpf is in a Whatsapp group with the parents who live in the buildings and organises parties for the children. One of her sons, she says, regularly goes down to the garden and plays with her neighbours’ dogs.

The architecture also provides entertainment of another kind for the boys. “Sometimes they like doing silly things that 12-year-olds tend to do, like pull moonies from the windows,” she says with only the slightest hint of disapproval. Once they’re safely at school, she throws open the shutters, partly to let in the breeze as she works but also because she knows that a well-known concert pianist, who lives above her, likes to practice every day at 11.00. “When he plays – oh my God,” she says. “This place is heaven.”

Lofty praise indeed for architecture’s capacity to make homes from houses and forge social connections, as well as for the vision of the building’s designer, Adolf Franz Heep. The émigré, known among contemporaries for gliding through the downtown in his distinctive slim bow ties, had arrived in Brazil in 1947 from Germany. He’d been helping with post-war reconstruction and separated from his Jewish wife by the Nazis. Following his escape across the Atlantic (at the age of 45 and using a fake passport) he joined the office of Frenchman Jacques Pilon and helped to complete the new HQ of newspaper O Estado de S Paulo, including subterranean printing presses. Heep’s solo designs for residential blocks soon followed. Relatively affordable and aimed at a burgeoning Brazilian middle class, Edifício Lausanne, with its red and turquoise aluminium blinds, is regularly name checked in today’s architectural guides; and at 47 storeys high, Edifício Italia still presides gracefully over Praça Republica.

Today, architect André Scarpa is convinced that the 1958 Locarno and Lugano buildings are Heep’s masterpiece. Scarpa knew of the buildings before he moved in and even once designed a shelving unit inspired by their H-shaped exterior window planters. He met his partner, Pedro Rossi, in 2023. After just two months they jumped at an available rental and moved in with their dogs Ipê and Gil. “I used to think that I loved Lausanne and lived in Lugano,” Scarpa says a little wistfully. “Now I think this design is better. Lausanne is very visual, with its coloured shutters, but Lugano and Locarno have light that flows through the apartments, the ceilings are high at 2.8 metres and every room connects perfectly.”

Higienópolis sill feels like a precious slice of old São Paulo in a city that likes to keep up with trends. On a Sunday, the queue for Mirian’s rotisserie chicken served from a hole-in-the-wall stretches round the block. Those waiting patiently are muttering that a much-loved bar has recently undergone a brutal refurbishment but another stalwart from the 1960s called Ugue’s still packs them in for feijoada (stew) and cold beers. Weekend runners in jogging kit are a common sight but you can spy uniformed maids walking packs of pedigree dogs, if you keep your eyes peeled.

Found beyond security gates (a 1980s addition), Lugano and Locarno lie perpendicular to the neighbourhood’s gently climbing main avenue. A mirror image of each another, they stand on either side of a narrow garden; their names spelled out in discreet sans serif ironmongery. A gardener sweeps the ochre paving stones with an old broom, clearing away branches and fruit from the guiambê shrubs, manacá-da-serra and palm trees. On the ground floor of each building are three apartments and two entrances with canopies held up by tapering white-tiled pillars. Inside, wide curving stairs – the steps and rails painted a soothing cream – take residents to other floors. While lower apartments have glass bricks that allow in plenty of light, the 12 floors above (with four apartments on each level) rely on windows that stretch their entire length.

The buildings are certainly attractive and welcoming places to live but they seem to be a particular draw to architecture obsessives. Agnaldo Farias, who teaches art and design at the nearby University of São Paulo, lives on the eighth floor of Lugano. “Heep was such a serious, meticulous architect with an eye for detail,” he says, citing the German’s education under Ernst May and Adolf Meyer at the Kunstschule in Frankfurt and years spent working with Le Corbusier in Paris. “Nothing escaped him. He brought ideas from Europe but adapted them to Brazil, understanding the climate, the problems,” he says with enthusiasm. “The ventilation windows above the main windows, for example. With their individual levers they’re so clever and they make for better living.”

With so much glass, however, each block offers views straight into the apartments of the opposite building. “Like Rear Window,” Farias says jokingly, in reference to the Alfred Hitchcock film. Scarpa admits that he had concerns when he first moved in. “I was worried about privacy but we respect each other, we all know each other,” he says. “I can look across and know [my neighbour] Claude is there today; that Juliana is back from holiday. Heep was interested in how the middle classes might live socially in a city as big and busy as São Paulo. If you have the privilege, this is a way to survive as a community without going crazy.”

Manoel Veiga, a painter who has lived on the second floor of Lugano for the past 18 years, says that there are more children here than when he first arrived. “I came at a moment of generational change,” he says. “My neighbours used to be much older and many had even lived here since the building was new but they were passing. I think my daughter, who is now 14, was one of the first children here.”

Veiga is proud that his apartment remains just as Heep designed it. Visitors step immediately into the living area, which stretches the entire depth of the floor plan, with a dining space to the rear. Here, Veiga and his wife, Nalu, have their morning coffee at an old bar table from Rio de Janeiro, watching the street behind the block come to life. On each shelf are what he calls his “nanocollections” – clusters of interesting objects that he’s picked up from antique markets and on his travels. There are vintage miniature spirits, little wooden boats and model airplanes, as well as magazines from 1966, the year that he was born. The kitchen runs into the old servants’ area and, like Strumpf, the artist has set up a workspace with a desk, chair and books in the former maid’s room. Across the adjoining corridor are the apartment’s three main bedrooms, though Veiga has turned one of these into a wet studio, a carpet of canvas protecting the floor from paint. Pinky-brown floorboards that run throughout are original, hence the care. “It is very hard to find peroba rosa wood anymore,” he says. “It’s very resistant, hard-wearing. Seven decades and I’ve never had any problems with termites.”

Veiga laments one detail, however. The previous owner changed the bathtub. To get a glimpse of the original, you need to visit art producer Thais Francoski’s nearby apartment, kept bright with its white walls and minimal decor. The 34-year-old has been in Locarno for three years, her first address in São Paulo after moving from Curitiba in the south of the country. She jokes that her neighbours know if she is having a party because her friends always end up dancing by the windows. Her bathroom, unchanged since Heep signed off on his project, is a vision of mid-century style: the walls are lined with aqua-blue tiles, matched by the chunky ceramic of the toilet, pear-shaped bidet and vast sunken tub.

Light flows in through the clouded glass bricks of the bathroom’s exterior wall. It also proves a party draw. “There are so many selfies by friends posted from this bathroom,” she says. The arrival of younger residents, as well as the pandemic, have loosened the community’s rules a little too. As well as sitting on benches outside to read or chat with neighbours, residents often take yoga mats or dumbbells down to the garden for exercise sessions, which was previously frowned upon. Children are not supposed to use skateboards but this has been allowed now too. Francoski bemoans that the communality only stretches so far, though. “The only complaint I have is that I can’t sunbathe in the garden in my bikini. It’s not allowed. We need sun though.” Heep, she tells Monocle, would have been on her side. After all, she opines, “this architecture is all about being healthy”.

This article is from Monocle’s March issue, The Monocle 100, which features our editors’ favourite 100 figures, destinations, objects and ideas.

Read the rest of the issue here.

Dubai’s property market has never lacked ambition but it has rarely looked like this. According to the Dubai Land Department, more than 40,000 licensed brokers now operate here. However, only a small fraction of them get close to the apex of the market, where single homes sell for the price of small European hotels and commissions are earned (or lost) on instinct alone. It’s a pure commission economy. There are no salaries or safety nets. Agents arrive from everywhere: Britons fleeing tired markets; Russians following capital; Arabs returning with regional clout; Europeans armed with pitch decks. Most don’t last. Those who do learn quickly that in Dubai, property is part performance, part intelligence.

For some, success is visual. They arrive sharp, glossy and conspicuously wealthy, mirroring the aspirations of their clients. Fast cars, heavy watches and an Instagram-ready life are not indulgences here – they’re tools. As one agent puts it, “If you’re selling to billionaires, you can’t look like you don’t belong in their world.” Others operate quietly. They talk less about marble finishes and more about noise corridors, flight paths and resale risk. They build businesses around discretion and repeat buyers. In a market saturated with sellers, sound advice has become a rare commodity.

The agents who survive at the top do so because they understand something fundamental: Dubai rewards conviction but punishes bluff. What matters most here isn’t where you came from or how good you look. The market only asks whether you can close a deal.

Ben Bandari

Company: Benco Real Estate

Years in business: 24

Biggest sale: AED500m (€115m)

Ben Bandari has seen Dubai at its most fragile and at its most inflated. He arrived in 2002, selling brochures and promises, long before the Palm Jumeirah had a shoreline worth photographing. Today he is widely considered to be the UAE’s most prolific broker, a status reinforced by his starring role in TV show Million Dollar Listing UAE and a contacts book that, he says, contains “at least 10 billionaires”.

Bandari understands visibility better than most. He is unapologetic about it. “If you’re not out there, you’re irrelevant,” he says. The cameras follow him, the Patek Philippe watch stays on his wrist and the deals often exceeding AED100m (€23m), continue to land. But longevity, he insists, matters more than glamour. “I stayed when others left,” he says of the 2008 crash. “That’s how reputations are built.”

The villa that he is selling on Billionaires’ Row on the Palm Jumeirah is valued at AED200m (€46m). It is a six-bedroom waterfront property with uninterrupted views, a rooftop area and a spacious basement; meanwhile, the artwork inside is worth the same as the house itself. Travertine marble, custom finishes and full water frontage make it one of the most expensive private homes currently on the market.

Bandari’s buyers are global and often already known to him. Sales are rarely public; they begin at private dinners or invitation-only events. “This isn’t about portals,” he says. “It’s about access.” In a market crowded with ambition, Bandari’s advantage is simple – he has been here longer than most and survived every cycle.

Dounia Fadi

Company: EXP Realty Dubai

Years in business: 20

Biggest sale: AED38m (€8.8m)

Dounia Fadi doesn’t sell noise. In Volante Tower, one of Downtown Dubai’s most discreet addresses, she moves with the ease of someone who has watched the city build itself from the ground up. Cartier on her wrist, Van Cleef at her neck, she speaks calmly, deliberately – more adviser than agent. “Luxury is an overused word in Dubai,” she says. “What matters is quality, serenity and trust.”

Fadi is one of the few brokers who have operated across every phase of Dubai’s modern property history, from the introduction of freehold laws to today’s hyper-regulated, data-driven market. She is also the only female mentor appointed by the Dubai Land Department, a role that she describes as “necessary but difficult” in an industry still dominated by men. “You need patience and consistency,” she says. “And you must think like an investor, not a salesperson.”

The property that she is selling here reflects that philosophy. The full-floor apartment in Volante, priced at AED60m (€13.8m), offers private lift access, generous proportions and hotel-grade services. Another listing in the same building, a penthouse valued at AED190m (€44m), pushes discretion even further. Residents have chefs, spas and security. “This is for people who don’t want to be seen,” says Fadi.

Her clients are global, high-net-worth and exacting. And they are less interested in brochures than in track records. Before she recommends anything, she asks herself, “Would I buy this myself?” It is a question that has helped to keep her relevant for two decades in a market that rarely forgives complacency.

Rami Wahood

Company: Fäm Properties

Years in business: 13

Biggest sale: AED61.5m (€14m)

Rami Wahood arrives in Al Wasl in a bright-blue Ferrari 812 Superfast, wearing loafers, a belt and a pocket square in matching shades. At 38, he looks every inch the modern Dubai broker: polished, relentless and hungry. “This is my life,” he says plainly. “I don’t have a balance.”

Born in Chicago to Syrian parents, Wahood started in Dubai at the bottom of the market, selling modest villas before climbing steadily into the eight-figure bracket. Today he is an executive partner at Fäm Properties. Exposure matters, he says, but consistency matters more. “You eat, sleep and breathe this,” he says. “That’s the job.”

The villa that he is selling in Al Wasl is priced at AED83m (€19m) and sits in one of the few freehold zones close to Downtown Dubai. With six bedrooms, Scandinavian-inspired architecture, Swedish wood cladding and views of the Burj Khalifa, it is deliberately restrained, a rarity in a city often accused of excess. “This is for people who understand taste,” says Wahood. “Minimalism is hard to do well.”

His buyers are often seasoned, internationally mobile and decisive. Wahood believes that presentation still matters. “You have to look the part,” he says. “Not for shallow reasons but because confidence is contagious.” In Dubai, ambition is not hidden. It arrives loudly and Wahood makes no apology for matching the tempo of the city.

Matt Siddell

Company: Independent

Years in business: More than 15

Biggest sale: Transactions exceeding AED250m (€58m)

Matt Siddell doesn’t look like a Dubai broker. Shirt unbuttoned and relaxed, he greets his clients on the 41st floor of a Dubai Harbour penthouse with spreadsheets rather than spectacle. “I don’t sell real estate,” he says. “I advise.”

Formerly based in London, Siddell arrived in Dubai with a network, not a brand. He avoided large agencies and built a business around retainers and risk analysis. “If your incentive is to close before someone else does, that’s a different agenda,” he says. “My clients are long term.”

The penthouse that he is showing is priced at AED24m (€5.5m). West-facing, with expansive terraces, it is positioned for appreciation rather than drama. Siddell talks about road completions, sight-lines and noise maps before he mentions views. “You make your money when you buy,” he says. “Not when you post it on Instagram.”

His clients, often family offices and institutional investors, value restraint. Helicopters are tools, not toys. “It’s easy to get carried away in Dubai,” he says. “Staying grounded is the real skill.” In a city that celebrates performance, Siddell’s success lies in refusing to perform at all.

This article is from Monocle’s March issue, The Monocle 100, which features our editors’ favourite 100 figures, destinations, objects and ideas.

Read the rest of the issue here.