This week Monocle has been at Mipim, the world’s largest real-estate fair and urban festival, which takes place in Cannes. Inside the Palais des Festivals, the main exhibition space, we built a Monocle Radio studio, hosted a party and drank a lot of coffee. The interviews that we gathered are destined for our podcasts and the magazine. But here are a few other takes on a week in the south of France.

Don’t get too smug

Monocle will be 20 years old next year. We’ve come a long way over that time and at Mipim numerous readers and partners sought us out at the Monocle Radio pavilion to share their appreciation. But sometimes, even after all this time and even when you are standing under a large “Monocle” sign, there can still be some explaining to do. “How long have you worked at Monaco Magazine,” one nice man asks. “It’s not Monaco Magazine, it’s Monocle,” I say, carefully emphasising every syllable to avoid any more confusion. I point at our lovely signage to stress the difference. He computes the new information. “But do you live in Monte Carlo?” he asks, refusing to believe that he’s got this totally wrong. I give him a copy of the magazine. At least he didn’t ask if I worked at Manacle Magazine, the trade title for those employed in the incarceration industry.

Some people have it figured out

In 1987, Kjetil Thorsen co-founded Snøhetta in Oslo. Today this multi-disciplinary design and architecture practice has more than 300 staff, allowing it to take on big projects around the world but still hold on to a studio ethos. Thorsen came in for an interview to talk about his work on a project in Turkey where, as always, he is being sensitive about sustainability. He’s a mountain of a man, gives a fantastic handshake and talks in a considered tone that would make him ordering toast sound enthralling and important. I could have spoken to him all day because he’s also figured out what he enjoys about his work, where the red lines are and what society needs from architecture. He’s a walking wisdom machine. I have added a note to my to-do list: “Find inner sage, practice handshake”.

Guest guessing

Honestly, I do listen to what they are saying with intent but when you are stood at the mics, your guest just a couple of feet in front of you, you do find yourself scanning their outfits, noting their body language (you can tell in seconds who will immediately engage with you, who is nervous or fears saying a single word that might play out badly with their electorate). It usually works out. The man who undoubtedly rocked the sharpest look was Manfredi Catella, CEO and chairman of real-estate company Coima. It was a wide-shouldered affair that had an air of a 1980s Armani number. The tie, the shirt, the slick grey hair – all so right. You’d buy anything from him. So that’s another one for the to-do list: “Buy an adventurous suit.”

Guest booking is an art form

And that’s why, at Mipim, I leave running the interview schedule to Carlota Rebelo, Monocle Radio’s executive producer. Everyone knows that she’s the gatekeeper and is not to be messed with. And anyway, the only person to corner me about getting someone on the schedule was a gentleman who wanted to know whether we’d like an interview with Miss Poland, who was in town to promote her nation’s real-estate offering. Fearing muddling Carlota’s planning, I declined. In the end, Carlota managed to secure 42 interviews with city leaders, famous architects and powerful developers. But she did come up short on the beauty queens.

That’s a wrap

By the time it came to pack up our stand (to be honest, that’s also not me but our wonderful engineer David Stevens), we had met players in the industry from Saudi Arabia and Florida, and been briefed on projects, politics and the players to watch. And I had also set one man right about my lack of Monaco media connections.

To read more columns by Andrew Tuck, click here. And to hear from just some of the people that we met at Mipim, listen to this week’s episode of ‘The Urbanist’ – the first of a two-part special from Cannes.

The richness of Paris’s reputation as a centre of literary creation veers close to being a trope. It was here, in 1791, that one of the first-ever copyright laws, designed to protect authors, was enacted. From Notre Dame de Paris to Les Misérables, the capital is also the setting of many of French literature’s best-known exports.

With its 400 bookshops, Paris has succeeded not only in ensuring their survival but enabling them to thrive as the economy of bookselling has undergone a transformation around the world. Ultra-competitive pricing from online marketplaces and skyrocketing commercial real-estate leases have combined to put bookshops in major cities in a difficult spot. But booksellers in Paris have two key advantages.

The first is France’s “Loi Lang”, named after president Francois Mitterrand’s culture minister, Jack Lang. This 1981 legislation, originally intended to protect independent bookshops from aggressive wholesaler pricing, outlawed discounts of more than five per cent on new releases, ensuring equal book prices nationwide. So even in the age of online retail, France is the country with the most bookshops per capita and is home to 3,500 independent bookshops. The second policy is one for which Parisian booksellers have former mayor Bertrand Delanoë to thank. The city of Paris started buying up Latin Quarter real estate with the objective of leasing it to bookshops at below market rate. The city is now landlord to 25 per cent of all bookshops across Paris.

Here, we visit 10 bookshops that exemplify Paris’s literary prowess. From preserving 15th-century manuscripts to feeding the appetite for bandes dessinées, these are the stores turning over new pages in the city’s literary history.

7L

Karl Lagerfeld’s voracious appetite for books was legendary. One story involves his chauffeur loading up a car full of books after the fashion designer visited a single bookshop. It seemed only natural, then, for Lagerfeld to start his own bookstore, 7L, at number seven Rue de Lille in 1999.

While the studio housing his personal book collection is sadly not open to the public, the bookshop at the front of the building offers one of Paris’s sleekest collections of coffee-table books on the visual arts, from architecture to street photography. Booksellers at 7L also offer a service that builds collections for clients seeking to fill shelves with works in tune with their personal literary and aesthetic interests.

After Lagerfeld’s death in 2019, Chanel acquired 7L and has big plans for its book club, the Salon 7L. It meets on the first Wednesday of every month for readings and cultural events as diverse as its founder’s artistic pursuits. “I wanted 7L to continue being a place of living creation, celebrating Karl Lagerfeld’s love of books and photography,” Laurence Delamare, 7L’s director, tells Monocle.

librairie7l.com

Date founded: 1999

Recommended book: Journal d’un Peintre suivi de Lettres Provencales (selected writings of arts patron Marie Laure de Noailles)

Number of titles: 2,500

La Procure

Of the handful of Parisian bookshops that have been open for more than 100 years, La Procure on Place Saint-Sulpice might be the most successful today. Originally a supplier of goods to the Catholic church – from pews to pipe organs – La Procure has become the European leader on religious books, with a thriving network of 26 shops and franchises across France.

When Monocle visits, Elie Khonde (pictured below), a priest from the Democratic Republic of Congo, is stocking up on volumes to take home after completing a summer seminary near Paris. But, over time, La Procure has expanded beyond prayer books, religious art and sculpture. More than half of the shop’s space is dedicated to a general audience, from political memoirs to bandes dessinées.

“We might advise others against it but we will order any book a customer requests,” says La Procure’s CEO, Thomas Jobbé-Duval. “It’s in bookshops, including ours, that the diversity of points of view is best fostered. We are almost the opposite of social media. Rather than narrowing down viewpoints, we facilitate openness and exchange.”

laprocure.com

Date founded: 1919

Other items on sale: Groceries made in monasteries or convents

Annual turnover: €8m

Librairie Paul Jammes

Librairie Paul Jammes is not the place for you to pick up an ephemeral beach read. Instead, every rare book inside is a piece of our collective history. The shop, which specialises in rare tomes and typography, proves that these objects aren’t a thing of the past – the digital world has made them more important.

Esther Jammes (pictured below) is the fourth generation of Jammes booksellers to take over the family business. When Monocle visits, she picks up a 1485 vellum astronomy book detailing lunar and solar eclipses in colour – its glaring red and yellow charts as bright as they must have been 500 years ago. Nearby, a statue of Gutenberg gazes approvingly at a printing press from the era of the French Revolution.

“People who come in out of curiosity sometimes ask whether this is a museum,” says Jammes. “I tell them that the difference is, for a price, you can leave with the exhibits you like.”

To be surrounded by these books, from typography catalogues to a first edition of Madame Bovary, is to be reminded that human progress – even in the age of smartphones and AI – owes a lot to books. That fact permeates France’s bookshop culture and its proud custodians, Jammes included.

librairiejammes.com

Date founded: 1925

Oldest book in the shop: 1485 edition of De Sphaera Mundi by Johannes de Sacro Bosco

Number of employees: 1

Artazart

In July 2000 journalists across Paris received a bright orange, Artazart-branded hard hat. Balled up inside was an invitation to attend the construction- site-themed opening party of a new bookshop and cultural space on the Canal Saint Martin: “Artazart, the bookstore of creation.” Next year,the shop will celebrate 25 years of housing graphic design publications and events.

“When we started, we would host up to two events a week,” says Jérôme Fournel, co-founder of Artazart. Sitting beside fellow founder Carl Huguenin, he recalls a time when running Artazart involved a lot of white paint and elbow grease to allow one graffiti artist after another to use the bookshop walls as a celebration of creativity. “We were never strictly a bookshop,” says Huguenin. “There isn’t really another structure like ours that intrinsically mixes illustration and books.”

Artazart’s offering, which ranges from magazines to limited-run artist books, is selected by Laetitia de la Laurencie, Artazart’s book curator. Her meticulous attention to paper quality, layouts and typographic choices when picking books earned her a place running Artazart alongside Huguenin and Fournel. “People come from around the world,” she says. “They are delighted to discover in France places with this kind of richness.”

artazart.com

Date founded: 2000

Recommended books: Homeland by Harry Gruyaert (Carl); Viaggi by Luigi Ghirri (Laetitia); Ishimoto, Lines and bodies – a monograph of late Japanese photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto (Jérôme)

Number of staff: 9

Palais de Tokyo

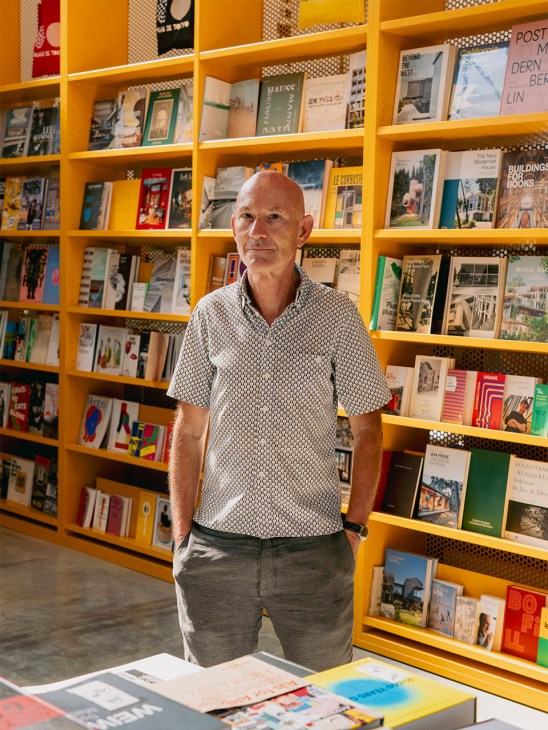

Alongside its dynamic contemporary art space – complete with a nightclub and gourmet café – Palais de Tokyo also boasts one of the coolest bookshops in Paris. Created in partnership with German art-books publisher Walther König and French literary magazine Cahiers d’Art, the store blends König’s expert eye and the magazine’s 1920s style to create a unique space that carries the biggest selection of art books in Paris.

“We have a big and luminous space where the public is not only attracted to the books on the tables and yellow shelves but also our colourful design objects and our magazines section,” says bookshop manager Arnaud Fremaux (pictured below). Among the trinkets that visitors can purchase, along with their favourite artists’ catalogues or the latest issue of Les Inrockuptibles magazine, are solar-powered lamps by Olafur Eliasson and tongue-in-cheek pills, by artist Dana Wyse, that promise profound improvements to your life or personality upon swallowing.

Beyond the curated selection and prime location in the heart of the Trocadéro, Fremaux considers the museum’s clientele the key ingredient that makes the bookshop such a vibrant space. “The Palais de Tokyo’s programme always attracts an interesting crowd, and the store is the place to spend a moment of relaxation after seeing an exhibition,” he says.

palaisdetokyo.com

Number of titles: 1,500

Recommended book: Donald Judd Furniture by the Judd Foundation and Mackbooks

Number of staff: 6

Yvon Lambert

Whether or not you live up to your family’s legacy is a classic French plot found in stories by writers from Roger Martin du Gard to Balzac. Perhaps that is why Ève Lambert, daughter of legendary Parisian gallerist Yvon Lambert, felt compelled to create a different legacy all together.

The sleek and cosy result is the Librairie Yvon Lambert, which offers publications on fine arts and photography, a well-stocked magazine wall and an art gallery. “We wanted to continue having a space to organise exhibitions, both with new artists and artists that Yvon has a history with,” Ève tells Monocle.

Ève continues to manage the space alongside her father. The pair also run the Yvon Lambert publishing house, which releases limited edition books featuring original works by artists who the Lamberts are close to. “Matisse and Picasso made such books, where there was a relationship between the artist and the author,” says Yvon. “That is the tradition I am carrying on.”

This combination of activities has been a hit with serious art aficionados as well as digital natives. “We have a very young audience that has always known smartphones – and they buy books,” says Ève. “It shows that there is continued affection for the book as an object.”

yvon-lambert.com

Date founded: 2017

Recommended book: Motel 42 by Éloïse Labarbe-Lafon

Recent exhibition: Allegoria Con Ortaggi, Pollame, Cesti E Vasellame, a sculpture exhibition by Luca Resta

Galignani

Italian publisher Giovanni Antonio Galignani of Lombardy established the Librairie Française et Étrangère bookshop in Paris in 1801. Today a stone plaque outside the door reads: “The first English bookshop established on the continent.” An astute businessman, Galignani also started an English newspaper widely read by the anglophone movers and shakers of the time, including Lord Byron and the Marquis de Lafayette. More than 200 years since its founding, the bookshop – now known simply as Galignani – is back in the hands of its founder’s descendants, with Anne Jeancourt-Galignani at the helm. “Our family had moved away from the profession of bookselling for a few generations,” says Jeancourt-Galignani. “I took over the leadership of the bookshop a few months ago, which has allowed me to reconnect with this family tradition.”

Inside the bookshop’s main room, browsing can require some athleticism. Accessing the titles on the upper shelves involves climbing tall ladders, while nearby stands are stacked with heavy volumes on art and photography. The selection is a testament to the bookshop’s history of adaptation: during the German occupation of Paris, a Nazi command post set up shop next door. With English books banned and unyielding enforcers close by, the shop pivoted to fine-arts books to survive.

galignani.fr

Date founded: 1801

Recommended book: Houris by Kamel Daoud. “A violent but necessary book.”

Annual turnover: €3.8m

Le Bon Marché

The most visited section of Le Bon Marché in the 7th arrondissement features neither handbags nor night creams. The historic department store’s foot-traffic crown instead goes to its vast bookshop, on the top floor, under the original glass roof designed by architects Louis-Charles Boileau and Gustave Eiffel. “Even more than the rest of the store, we have a clientèle that comes very often,” head buyer Noëlle Chini tells Monocle. “We have also had a more international clientele drawn by our books on art, decoration, architecture and fashion.”

The selection of literature, cookbooks and bandes dessinées covers all bases but under Chini, who got her start at Le Bon Marché selling postcards nearly 30 years ago, the bookshop has emphasised what she calls “beautiful books”. “Fashion and culture have always carried the store, so we wanted to translate that to the bookshop,” she says.

As well as a well-chosen selection of reading materials, you’ll also find a luxury stationery shop, where patrons can customise notebooks and pens from brands such as Caran d’Ache and Leuchtturm1917. “This is a neighbourhood of publishers,” says Chini. “For us, it makes sense to talk about both reading and writing at the same time.”

lebonmarche.com

Date founded: 2010 in its current form, but Christmas-time book sales date back to the 1880s

Recommended book: Cabane by Abel Quentin

Number of book events per year: About 30

Librairie Vignettes

Comic books are too often considered the province of children or anoraks. In France and Belgium, however, bande dessinée (BD) is rightly recognised as a bone fide art form, on the same level as music, architecture or poetry. It’s also a thriving business: in 2023, 75 million BDs were sold in France, the third-best year ever for the industry. “France has a very unique BD culture,” Charlotte Foucault, one of the three partners of Librairie Vignettes, tells Monocle. “We are open to all bande dessinées genres, which isn’t the case for Americans or the Japanese.”

Foucault, Ariane Roland and Roxane Pingal had been booksellers together at a larger BD specialist when they decided to strike out on their own in 2020 and open Librairie Vignettes. They offer edgier, more on-the-pulse works and less merchandise now that they are in charge. “Back then, we used to sell a lot of action figures,” says Foucault. “Our idea of bande dessinée is to showcase every genre, including stuff that we don’t like.”

At Vignettes, classics featuring characters such as Tintin and Asterix have their place beside thornier contemporary explorations of topics including feminism or the Israel-Gaza war. This selection reflects the medium’s place in France – as cultural canon with an appeal that continues to bridge the generations.

canalbd.net/vignettes

Date founded: 2020

Recommended book: Madeleine, Résistante, a BD series about historic Résistance figure Madeleine Riffaud

Recent author event: Brothers Ulysse & Gaspard Vry for the release of Un Monde en Pièces

Chantelivre

Great readers are not born but places like Chantelivre help to make them. “The original idea was to create a space where you would learn reading through fun, discovery and emotions, and where everyone felt welcome, no matter their previous approach to books,” Alexandra Flacsu, co-director of Chantelivre, tells Monocle. Founded in 1974 as the first specialised children’s bookshop in France, Chantelivre revolutionised the literary landscape with its playful approach to reading. “There were comfortable spaces with pillows for children to read in and things were built to fit their height, something that hadn’t really been done before,” says Flacsu.

The 6th arrondissement store was renovated in 2023, and now boasts a complete reading lounge for kids and “la maison des histoires” (the stories house), a dedicated place where children can play and reading sessions with authors and actors are held. Through these activities, books are used not only as mediums for learning but for discovery and moments of sharing. “It’s our way to make reading come alive,” says Flacsu. Today a quarter of Chantelivre’s books are for adults, a choice that she considers to be more inclusive. “We wanted to create a family bookshop. People can come with their toddlers or teens and enjoy a moment together.”

chantelivre-paris.com

Number of titles: 30,000

Recommended books: Lettres d’amour de 0 à 10 by Susie Morgenstern; Graines de Cheffes by Lily LaMotte; Bandes de Boucan by Anais Sautier

Number of employees: 19

Protecting books in a digital age

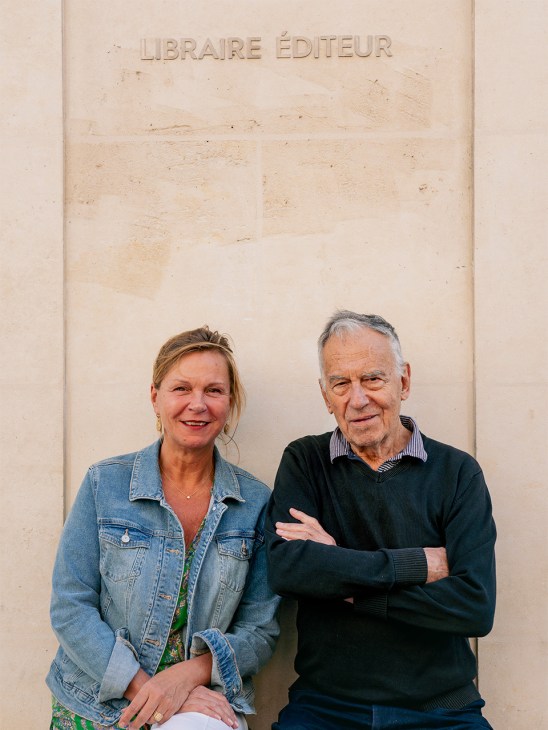

Librairie Michel Bouvier

Every visit to my uncle Michel Bouvier’s rare-books shop in Saint Germain des Prés yields a captivating new tale about a recent acquisition (writes Simon Bouvier). Prints of Soviet-era propaganda photos taken by Ukrainian photographer Yevgeny Khaldei. A handwritten letter by a young Claude Monet breathlessly recounting a recent visit to an exhibition. A tiny medieval prayer book with a golden clasp. Every object carries meaning beyond its message. Whether glossy paper or pristine vellum, its form holds a snapshot of human interactions.

Practical, economic and strategic considerations have shifted the attention of consumers and policymakers to the digital realm. But bookshops have something that the efficiency-driven economy of algorithms and convenience can’t replicate.

“On the internet, you find what you seek,” says my uncle (pictured). “But in a bookshop, you find what you weren’t looking for.” This sense of discovery doesn’t just result in a potential sale. It also fosters the community and awareness that are the lifeblood of civic life.

Thanks to my uncle, I know that bookshops matter. Whether you are a powerful mayor or humble reader, support for them shouldn’t merely be a political afterthought or a hip badge of honour. They require serious investment that pays priceless dividends.

Simon Bouvier is Monocle’s Paris bureau chief.

Further reading:

– Monocle’s full city guide to Paris

– Leaf through London with 10 bookshops that are bound to please

– New York’s 10 best lesser-known bookshops

After standing on the scales, feeling the chilly steel of the stethoscope on its chest and going, “Ahhhhh,” the global art market’s annual health check is complete. It arrives in the form of the yearly Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report, authored by Clare McAndrew, published yesterday and examined further at last night’s live event at The Royal Academy of Arts in London.

The evaluation, taken from sales data offered by global dealers and auction houses, is much anticipated in an art world ever keen to know if its sun tan and gleaming teeth are a sign of rude health or are obscuring underlying health concerns. So how’s the patient faring?

Overall, global sales increased by 4 per cent in 2025 to an estimated $59.6bn (€51.6bn), marking a return to growth after two years of contraction. Auctions did the best with a notable 9 per cent rise, driven by strong sales for works sold under the hammer for more than $10m (€8.7m). Dealer sales rose by 2 per cent. These are modest figures overall, though, considering the market was valued at $67.8bn (€59bn) in 2022. So the patient’s celebratory drink after receiving its results might be more a glass of sauvignon blanc than a magnum of Krug.

While “ultra-contemporary” work drove the market out of the pandemic slump, the report shows that sales by contemporary dealers were stagnant in 2025. The numbers also indicate “a structural rebalancing toward established artists and older sectors”, according to the survey. Despite Frida Kahlo’s “El sueño (La cama)” becoming the most expensive work by a female artist when it sold at Sotheby’s last November, the rest of the top-10 auction sales were all paintings by men – the list headed by three Gustav Klimt works – and all sold at Sotheby’s in that same, rather lavish, week.

Does this mean the market looks generally dependable but increasingly conservative? “The big action was the older, established artists that seem to be selling the best,” says McAndrew. “As it happens, because of historical biases, that means there are a lot of male artists in those older sectors.” She notes that auctions and dealers leaned similarly trad, a trend that, she adds, “probably suits the times, in that people are a little bit risk averse. There’s so much rubbish going on around the world that if you want something more certain, you’ll go for those established names.” It seems then that the world’s bellwether collectors are currently in a battening-down-the-hatches mood.

For dealers the highest and lowest price points did the most business, while the middling – “works priced in the five or six figures” – proved “more difficult”, according to McAndrew. Big names at big galleries and the tiddlers with attitude and curatorial cleverness seem to have won through.

Other than the big-money Klimts and Kahlos going under the hammer, many of the art world’s headlines in 2025 concerned the closure of some big-name galleries including Blum, Sperone Westwater and, last month, the Stephen Friedman Gallery. “In no way do I want to diminish these often irreplaceable galleries going but generally this is a world of real resilience compared with the lifespan of other businesses,” says McAndrew.

An encouraging note on which to end is the fact that in-person sales continued to increase because, as McAndrew concludes, “you’re not just buying an item, you’re buying a whole world around it. The art world is, in fact, much more of a service industry than a goods industry.” The diagnosis? Maybe stick to sorbet for pudding – and do keep up the exercise.

Robert Bound is a contributing editor at Monocle. For more from Bound, read:

– Team of rivals: Tate Britain’s Turner and Constable exhibition shows us two ways of seeing the world

– After seven decades of creativity, David Gentleman shares advice for aspiring artists

– Topless cars are still the most fun you can have with your clothes on

Joachim Trier’s Norwegian drama Sentimental Value is a poignant exploration of family, fame and the complexities that often come with both. Featuring an ensemble cast including Renate Reinsve, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Stellan Skarsgård and Elle Fanning, the film follows two sisters who reunite with their estranged father as he attempts to restart an ailing directorial career. The title has been nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

The director has become well-known on the international cinema circuit, drawing acclaim for the Scandinavian film scene. His 2021 feature, The Worst Person in the World, was nominated for several major awards including the Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival and Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards. For Sentimental Value, Trier worked with his longtime writing partner, Eskil Vogt, to create a story that meditates on the intricacies of family and the passing of time.

Trier joined Monocle senior correspondent Fernando Augusto Pacheco to discuss how his personal life informed the film’s narrative, getting the casting right and how cinema can bring people together in trying times.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

As a father of two girls and coming from a film-industry family, is it fair to say that Sentimental Value feels personal to you?

I’m the kind of director who sits down and tries to create a story about where I am in life. Every time I make a film, I start from scratch with Eskil Vogt, my cowriter. This time we realised that we were at a moment in our lives in which we both have children – Eskil and I have two children each – our parents are still around [and] we’re sensing how fast time flies. As you mentioned, my grandfather was a filmmaker. My parents worked with films. I grew up on film sets. That’s my life and I’m very grateful for being allowed to make them. But we didn’t start out thinking that we would make a film about film people.

The scene where the sisters [Nora and Agnes] embrace towards the end of the film – it’s so pure and beautiful.

Thank you. Another thing that motivated this [project] was that I had a great collaboration with [the actor] Renate Reinsve in The Worst Person in the World and I really wanted to work with her again. She has an amazing capacity for levity and humor but also deep dramatic work. As I had gotten to know her even better, I felt that there was something to explore in the character of Nora – a workaholic actor who is very successful but somehow finds it hard to create a sense of home or connectedness. Then we had to find a sister to match her and also match [Renate] as a performer. We found a wonderful actor in Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas.

In the film we see the National Theater where Nora, the older sister, works, which is the place of imagination. It’s like the left part of the brain. [Her sister] Agnes goes to the National Archive [of Norway] where all [our society’s] facts are stored and researches family history. That’s kind of like the right brain. Between these sisters and between these places of societal understanding of who we are in terms of narrative, there’s a space for family in the movie.

You could have made the father, Gustav, played by Stellan Skarsgård, an unlikable character, but there’s some tenderness for him in the film.

He’s not perfect at all but there is tenderness, right? The father – this director, Gustav Borg – hasn’t made a film in 15 years but still thinks that he’s the king of the world. We cast Stellan Skarsgård because he’s such a warm, sympathetic man. We hopefully created a more three-dimensional character with nuance. It’s a story about reconciliation. It’s about understanding that inside every difficult parent there is also perhaps a wounded child, and to grapple with that. What is reconciliation in the family? I didn’t want to make a film with cheap solutions where, [the characters] talk about it and it’s all fine. That’s not how life works.

Tell us more about the Norwegian film scene. It’s experiencing a boom at the moment.

I care more about the cinema world as a whole, and I work with collaborators from around the world. But I will say this: the wonderful thing about the Nordic-film boom is seeing that personal cinema is being allowed to be made financially. This could encourage other governments to really support the arts.

At this moment, we need to take art seriously. We need, in complicated times in society and in the world, to have reflections of stories on a deeper level. [To] try to communicate, create empathy, meet in cinemas, meet in theaters, meet in books and understand on a deeper level that we are more alike than different. Art can be a place for reconciliation.

It seems as though people are craving more personal stories in the cinema. Maybe they are getting tired of all the remakes and rehashed stories.

We’ve been through a big wave of superhero features and certain formulas, and people want development and forward momentum. They want change. They want to see something new.

Listen to the full conversation on ‘The Monocle Weekly’.

The UAE has long lived with an uneasy proximity to Iran. Just 55km of water separates the two coastlines – a narrow stretch known as the Strait of Hormuz that has always carried strategic weight. But in the current conflict, that geography seems more acute.

In the first 11 days of hostilities alone, more than 1,700 Iranian missiles and drones were launched toward the UAE: far more than at any other Gulf state and several times the number fired at Qatar. By some estimates, about 58 per cent of Iran’s attacks on Gulf Cooperation Council countries have been directed at the Emirates.

The scale raises an obvious question: why the UAE?

Part of the answer lies in geopolitics. The Emirates sits at the intersection of several alliances that Tehran distrusts, namely its deep security ties with the US and the diplomatic opening with Israel through the Abraham Accords. “From Tehran’s perspective, the UAE is enemy number one in terms of Arab states in the Gulf,” says Brendon J Cannon, a fellow at the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Abu Dhabi. “It’s also, frankly, a victim of its own success.”

Success in this case means visibility. Over the past two decades the UAE – and Dubai in particular – has positioned itself as a crossroads for global business, finance and travel. Its airports are among the busiest on earth, its airlines connect continents and its ports move goods throughout the world economy. For Iran, hitting the UAE carries symbolic and practical weight. “Everybody around the world knows about Dubai,” says Cannon. “So there is an effect of attempting to cut the UAE down to size, and to shake that ironclad view for investors and tourists around the world that the UAE is this oasis of calm.”

That calculation helps explain why Iranian strikes have not been limited to military targets. While US bases in the Emirates have been hit, so too have major civilian sites, including Abu Dhabi and Dubai airports and infrastructure around Jebel Ali port. Debris from one intercepted drone even struck a luxury hotel on The Palm. In other words the objective appears to go beyond battlefield retaliation. It is also about creating disruption in one of the world’s most visible economic hubs.

Proximity matters too. The UAE lies well within range of Iran’s large arsenal of less costly short-range missiles and drones. Unlike Israel or more distant Gulf states, the Emirates can be reached quickly and cheaply by weapons that Tehran already has in abundance. That logistical advantage makes it an obvious pressure point.

At the same time, Iran appears intent on demonstrating that its retaliation can ripple beyond the immediate theatre of war. If Tehran sees the conflict as existential – a struggle for the survival of the regime itself – the logic is to widen the impact as much as possible. “This is an all-or-nothing struggle for the Iranian regime right now,” Cannon says. “The strikes by the US and Israel have led the Iranians to take the gloves off.” Yet there might be another reason that the UAE has remained a central target: it refuses to shut down.

Despite repeated alerts and missile interceptions, life in the Emirates has continued with surprising normality. Offices remain open and the country’s commercial machine has largely kept running. The message from Abu Dhabi and Dubai has been one of resilience rather than retreat. For Tehran that normality might be provocative in and of itself. These continued attacks test whether the UAE’s reputation as a safe haven can withstand sustained pressure. “Part of the aim is to shake that perception,” Cannon adds. But the real disruption is not entirely visible. Flight schedules have faced periodic interruptions as airspace warnings trigger temporary diversions, and some hotels have closed entire floors while quietly trimming prices as bookings soften. Oil markets have also reacted to the region’s instability. The UAE’s economic cogs continue to turn but the conflict proves that insulation from geopolitical turbulence is impossible.

So far the country’s defence systems have limited the damage. Officials say that the UAE has intercepted roughly 93 per cent of incoming missiles and drones, with fighter jets and air-defence batteries knocking down projectiles before they reach urban areas. Footage released by authorities shows air-to-air interceptions followed by the blunt confirmation: “Target destroyed.” The display is both a military and a political message – reassurance to residents, investors and visitors that the country can defend itself.

Privately, however, Emirati officials are angry. The UAE had made clear that it would not allow its territory or airspace to be used by the US to launch attacks on Iran. The hope was that this stance might limit retaliation. It did not. “They’re justifiably furious,” Cannon says. “Iran is a problem – it’s an existential threat to the UAE.”

That displeasure is unlikely to alter the Emirates’ strategic direction. If anything, the conflict might reinforce it. Closer defence ties with technologically advanced partners – including Israel – and greater investment in domestic military capability are likely outcomes. At the same time, geography ensures that the UAE and Iran cannot simply disengage. Trade links, shared waterways and economic realities mean that the two neighbours will eventually have to return to some form of pragmatic coexistence. But the trust deficit has widened dramatically.

For Tehran, striking the UAE might serve multiple strategic goals at once: retaliation against the US and Israel, pressure on a key Gulf adversary and disruption of a global economic hub. For the Emirates the lesson is stark: success, visibility and openness make a country influential – but they can also make it a target.

Imagine yourself in a queue. It’s one-hour long and stretches as far behind you as it stretches ahead. It’s also composed almost exclusively of men wearing the same outfit, the products of a recognisable brand, whose clothes you have admired in the past. The queue winds its way into an indeterminate space where examples of these clothes hang from wobbly rails in large numbers. Cardboard boxes are filled with brand-new scarves and ties.

The atmosphere is competitive. You look at what the men are wearing, as well as what’s on the hangers. The clothes, you think, as a tall man elbows his way between you and an unsteady rack, don’t look very nice anymore. And the tall man has extremely sharp elbows.

Popping into a sample sale might sound like an agreeable way to pass an idle hour between lunch and your next meeting. It might even seem like an interesting opportunity to get a handle on the locals as you stroll around a foreign fashion capital and snag a bargain at the same time. Buyer, beware.

A label’s carefully constructed identity and the logic of manufactured scarcity – desire piqued through limitation – go out the window at a sample sale. The true value of visual merchandising is thrown into sharp relief. The odd gem nestles among a case study in bad inventory planning. Over-ordered seasonal misfires, the stuff that didn’t sell at the time, is given a second, cut-price chance. Despite the atmosphere and the sharp elbows, the approach seems to work. With prices lowered, the question “Why buy?” gives way to “Why not?”

It’s not hard to find an unpleasant shopping experience in 2026. And it’s not difficult to learn why – and how – the culture of sales is contributing to an environment of overconsumption and unrealistic consumer expectations. Smaller brands and businesses that try to do interesting things struggle to compete in a market where someone, somewhere, is always knocking two-digit per cent reductions off the price.

What’s trickier is tracking down the boutiques where expertise and dedication are given free rein to present a thoughtful selection of garments in their best light. Where people passionate about their work, who know more than you do and are prepared to spend the time sharing the benefits of their knowledge with you – and your wardrobe. A good retail experience, after all, treads a fine line between deliberation and impulsiveness: a long-considered purchase can layer very nicely over a shirt bought on a whim. At a sample sale, value collapses like a cardboard box overstuffed with last year’s T-shirts.

Not every sample sale is the same. Some truly live up to their name; there are unique pieces and bargains to be found. For the rest, well, there’s no doubt that selling surplus stock to fanboys is a better alternative than sending it straight to landfill. But better yet would be to mitigate the risk of that surplus. The challenge for brands is finding the sweet spot by limiting production runs, not to manufacture scarcity but instead to manufacture responsibility. Customers can make it easier by short-circuiting discount hysteria to ensure that impulse is informed, reflecting critically on the thoughtless desire that prompts men to queue for an hour in the rain, for example. In doing so we might find ourselves prepared to spend a little more and buy a little less.

Augustin Macellari is a Paris-based journalist and regular Monocle contributor. If you’re after a good place to shop, why not check out our City Guides?

And for more on boutiques and well-considered retail…

– Amid retail-sector uncertainty, boutiques and catalogues are making a comeback

– Best boutiques in the world: Neighbour, Vancouver

– Brooklyn boutique L’Ensemble proves that privacy and intimacy are the new luxury

Missile alerts have become a grim new soundtrack in parts of the Gulf. As the US and Israel-led war with Iran stretches into a third week, the UAE finds itself on the front line of a conflict that has rattled aviation routes, shaken global supply chains and transformed the Strait of Hormuz – one of the world’s most vital maritime corridors – into dangerous waters.

More than 2,000 threats, including missiles and drones, have been launched towards the region; with the UAE absorbing a large share of the attacks. Yet Abu Dhabi insists that escalation is not the answer. Speaking to Monocle, Noura bint Mohammed Al Kaabi, the UAE’s minister of state at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, says the country remains focused on defence, diplomacy and maintaining stability at home, even as warning alerts continue to flash across residents’ phones.

Al Kaabi argues that the UAE’s openness and economic model have made it a target for Tehran but insists that the country will not be drawn into a wider war. Instead, she points to the resilience of the UAE’s diverse population, the success of its missile-defence systems and a diplomatic push at the United Nations to condemn the attacks.

“The UAE did not seek this conflict,” she says. “But we will always take the necessary actions to protect our sovereignty and our people.” Here, Al Kaabi speaks to Monocle about the conflict’s impact on the UAE, the risks to global trade and why the country believes that de-escalation remains the only viable path forward.

We’re now entering the third week of this conflict. What effect has it had on the country and the wider Gulf?

Just minutes ago our alert system went off again. Shortly afterwards the authorities reassured us that the threat had been intercepted. What I can say is that the UAE’s state of defence is strong and precise. There have been more than 2,000 threats – missiles and drones – targeting the region. These attacks affect everything: the economy, logistics, airspace and, most importantly, civilians. We have been very clear: the UAE did not seek this conflict. But we will always take the necessary actions to protect our sovereignty and the safety of everyone who calls the UAE home.

About 60 per cent of Iran’s attacks on the GCC have been directed at the UAE. What issue has Iran got with the UAE that made it target you like this?

Iran claims that it is attacking military interests but what it is quite the opposite. The UAE model makes Iran uncomfortable. We are a country that shows the world it can be open and that people from different cultures can live together in harmony. This stands in contrast to the ideology that the Iranian regime promotes. In difficult times you see people’s true colours – you see who your friends really are.

Some might argue that Iran resents the UAE’s success over the past few decades.

We have a large Iranian community in the UAE – people who have built businesses and families here. That’s why it raises a deeper question: if you are launching attacks in this region, do you not care about the safety of your own citizens who live here? We have had injuries and casualties and we consider every victim as one of ours, regardless of nationality. Responsible leadership should care about the safety of its citizens wherever they are in the world.

The number of attacks has dropped slightly in recent days. Do you believe that Iran is recalibrating and are you prepared for that?

It’s difficult to predict. What matters is not a temporary drop in numbers but whether the attacks stop entirely. We remember when the UAE was targeted by the Houthis in 2022. Even though there were only a few missiles, we still remember that day. Our focus now is keeping the country safe. The Ministry of Defence has done remarkable work intercepting drones and missiles, often using innovative methods.

The UAE has intercepted most incoming attacks but why hasn’t it responded militarily?

Because we understand the consequences. Escalation would bring a much wider war to our doorstep and that is something we want to avoid. The UAE is acting responsibly. We are pursuing diplomatic channels, including efforts at the United Nations, and we are working with our partners to condemn these attacks through international law.

The conflict is also affecting global trade. What concerns do you have about the Strait of Hormuz?

Any disruption to the Strait of Hormuz affects global supply chains. It is not only a Gulf issue – it is a global concern. This is why there is such strong international interest in de-escalation. Countries around the world understand that instability in this corridor affects everyone.

This conflict has damaged the UAE’s reputation for safety and stability. How will you rebuild it?

Quite the opposite. This moment is proving those qualities. Look at the response from people living here – the UAE community comes from every corner of the world and it has shown extraordinary resilience. That unity is a powerful signal of what the UAE stands for.

Tourism has taken a huge hit during the conflict. Is that recoverable?

The impact has actually been less than we expected. More than 1,200 hotels remain open and some 40,000 tourism-linked businesses are still operating. We supported travellers affected by disruptions, issuing emergency visas and covering accommodation when needed. When the situation stabilises, tourism will rebound very quickly.

A UN Security Council resolution condemning Iran’s actions is being discussed. How significant is that?

International legitimacy matters. When organisations such as the United Nations clearly condemn attacks such as these, it reinforces the integrity of the international order. For the UAE and the GCC, it’s about ensuring that aggression against sovereign nations cannot be normalised.

When the conflict ends, how might the UAE reposition itself diplomatically? Does it distance itself from the US and Israel? Does co-operation between GCC nations strengthen? Are you more wary of Iran than before?

The UAE will always seek partnerships with countries that respect its sovereignty and share a vision for a prosperous future. We are not a large country, so we must be agile and build strong relationships around the world. Initiatives such as the Abraham Accords reflect our belief in moving beyond historical divisions and building bridges. Our focus remains on the future – technology, innovation and co-operation.

Madrid has many things going for it – clement weather, inspiring museums and patatas bravas on every restaurant menu. Despite being home to studios such as Jorge Penadés and Alvaro Catalan de Ocon, the Spanish capital has never been an essential stop on the design industry’s annual circuit. But with the city’s first collectable design fair having just wrapped up, is that about to change?

On the opening day of Forma Design Fair Madrid, founder Álvaro Matías declared that his aim was “to create the most beautiful design shop that you could see in Spain.” It’s an ambition that he delivered on at the Matadero Madrid cultural centre, where booths were occupied by a mix of independent designers, group shows and galleries. Highlights included Arturo Álvarez’s sculptural lighting designs, which use wire to create playful, mesmeric shadows, and La Ebanistería, where a crowd “oohed” and “aahed” when a series of wall-mounted black boxes were opened one by one. The sculpture revealed itself to be one giant cabinet and, in doing so, a piece that blurred the boundaries between art and design.

Forma artistic directors Antonio Jesús Luna and Emerio Arena are well known on the international design scene as the co-editors of Room Diseño magazine. It’s a position that helped them to attract a mix of international participants, from French firm Maison Parisienne to Colombia’s Tu Taller Design.

As Luna and Arena walked me through the fair, they stressed how many of the designers on show apply traditional Spanish craft techniques to contemporary designs. It chimes with a broader, global shift towards work dubbed “collectable”, which celebrates artisanship and limited-edition works. At the booth of Guadalix-de-la-Sierra-based Van den Heede you could see the ethos reflected in sleek, handmade wooden tables and chairs. So too at Alfombras Peña’s booth, a benchmark demonstration of traditional weaving techniques used to create large, elegant rugs. In a similar vein, material specialist Cosentino presented a table, lamp and counter made from natural stone and minerals (pictured above) while Barcelona-based Joshua Linacisoro showcased a collection of lighting forged from the Basque landscape (pictured below, right).The message was that Spain has been doing this type of work for a long time – it just might not have been calling it collectable design.

Indeed, Forma is a shiny new ending to the almost-decade-old Madrid Design Festival, which takes place over a month and draws in headline acts such as Spanish fashion house Loewe. The festival is more experiential, with talks, open showrooms, workshops, exhibitions and pop-up shops. This year Manera magazine joined up with Spanish furniture and lifestyle brands The Maisie and Santa Living to stage an exhibition at the Museo San Isidro. The institution is home to Roman mosaics and terracotta artefacts that tell the long history of Madrid. The contemporary designs – chairs, vases and a giant lamp on spidery legs that swayed and wobbled – were exhibited in the museum’s courtyard. There, brought alive by bright natural light and hidden among mythic sculptures of Hercules and Prometheus, the objects began to tell a new story about the evolution of craft and humanity. These are more than just pieces that you’d quite like in your living room.

Madrid’s entry into the design-fair space is overdue but unsurprising – the designers have been here quietly creating the scene for years. As Matías told me, they have stuck around in the city because they feel like it’s on the brink of something. “This is about to begin,” he says. Watch this space.

Sophie Monaghan-Coombs is Monocle’s associate editor of culture. For more on Spanish design, read our report on the evolution of brands such as Zara Home and Kave.

Fashion weeks have suffered from remarkably poor timing in recent years. From news of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years later, the latest edition of the womenswear fashion month, which concluded in Paris yesterday, was overshadowed by reports of the US-Israel war on Iran, ships being sunk off the coast of Sri Lanka and the price of oil skyrocketing as a result. To shift from these headlines to the latest collections being unveiled on the runway requires acknowledging that the fashion industry represents the livelihood of millions of people worldwide – from garment workers and publicists clutching iPads outside of shows to casting agents, caterers, choreographers, set designers and more. While the spectacle of a fashion week feels frivolous at times, the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode estimates that Paris Fashion Week generates about €1.2bn in economic revenue for the host city.

Fashion, when executed to the levels seen in recent weeks, holds up a mirror to the times we live in or, at the very least, provides some needed escapism. In Paris, luxury houses continued to raise the bar following a year of creative-director switch-ups and executive reshuffles. As the dust settles, we can now gauge which pairing of designer and maison is emerging as the winning formula. Take, for example, Dior (pictured, above). The label’s Northern Irish creative director, Jonathan Anderson, honed in on the elements of the house codes that resonate with his own sensibility, most notably a love for botany and playing with complex silhouettes. A closer look reveals the perfectly executed details – from buttons running down the seams of trousers to silvery tulle peeping out of a Bar jacket.

Dior isn’t the only label in the LVMH stable to come careening out the gates this season. The French luxury conglomerate is sustaining momentum across the board with a portfolio of brands that are carving out different niches. Celine, Givenchy and Loewe all presented womenswear collections, each with distinct feels. From neoprene scuba-diving-derived shoes at Loewe by Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez to Sarah Burton’s sharp suiting and flattering eveningwear at Givenchy, the luxury-goods group is casting a wide net, offering something for everyone.

But is Chanel’s Matthieu Blazy the ultimate winner? The debut collection by the Franco-Belgian creative director hit the racks of the French house’s boutiques over the weekend and reports of a shopping frenzy on Rue Cambon quickly became the talk of the town. On Monday evening, showgoers paraded into the Grand Palais sporting the latest square-toe pumps and iterations of Chanel flap bags (pictured, above). On the runway, models came out in iridescent tweed sets, belted drop-waist skirts and monochromatic coats. As Blazy took his bow, the room erupted into applause. And as excitement for Chanel’s new era translates into real in-shop sales, it offers wider hope for the industry at large, even in the most uncertain of times.

Grace Charlton is Monocle’s associate editor for design and fashion. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

More style from Paris? You’re in luck

• Paris Fashion Week Men’s celebrated everyday life amid geopolitical uncertainty

• How curator Olivier Gabet brought fashion back into focus at the Louvre

• Interview: Bruno Pavlovsky on Chanel’s Matthieu Blazy chapter: ‘The brand is back’

Iran has a new supreme leader in Mojtaba Khamenei, second son of his late father and predecessor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was killed in late February as the war between the US, Israel and Iran broke out. Though the 56-year-old Mojtaba has long been suspected of being influential behind the scenes, he has generally been circumspect, verging on reclusive.

Amid the ongoing war, Mojtaba Khamenei’s appointment is a direct rebuttal of US president Donald Trump, who said the “worst case” scenario was that the elder Khamenei’s successor would be “as bad as the previous person”. Though regime change in Tehran has never been expressly part of the US war effort’s goals, Trump has said that he would expect his country to have a role in the appointment of Iran’s next supreme leader, and has repeatedly pushed Iranians to rise up against their government.

To get a better picture of Mojtaba Khamenei, the ways in which his appointment will impact the war and how he is viewed by Iranians, Monocle spoke with Laura James, deputy director of analysis and a senior Middle East analyst at Oxford Analytica.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Mojtaba Khamenei has long been suspected of having strong influence behind the scenes but he’s not known to have ever made a major public appearance. What do we know about him?

We know that he was very close to his father, that he was seen as a gatekeeper. We know rumours about him, which are that [his beliefs] are very much on the hardline side, that he has strong military connections. We know that he doesn’t tick all the boxes for a peacetime supreme leader, and that he hasn’t had senior clerical posts or even senior political posts that you would expect. [His appointment] is a wartime decision and the symbolism is an important part of it.

Does it seem more likely that this is Iran’s leadership – or whatever remains of it – sending a signal of both defiance and continuity, rather than anointing somebody who is actually going to be making big decisions?

Both can be true. He might not have succeeded in peacetime but appointing him now says there is continuity, there is resistance, there is revenge on the US. That doesn’t mean that he won’t step forward and take on that role and make it his own, as his father did more than 30 years ago. Much depends on whether he survives; there were rumours that he had been hit by earlier strikes. So there are a lot of unknowns there but what has become clear is that the hardliners are making the dominant decisions at the moment in Tehran.

After more than a week of war, can we discern the chain of command? There have been suggestions that what we are seeing is a pre-war plan enacted by Iran – that power, command and control would be diffused and decentralised. We’ve had mixed messages from president Masoud Pezeshkian, who last week apologised to Iran’s Arab neighbours for the strikes and said they would stop, only for them to continue.

That was definitely a strange mix up. It followed earlier comments by the [Iranian] foreign minister that strikes on Oman hadn’t been intended, and there were warnings even before the conflict that Iran had plans to devolve command and control [to allow] individual commanders to make independent decisions. That is certainly happening but I don’t think that necessarily means a full loss of command and control. We’re not looking at a collapsing state. The leadership has decided that it makes sense to increase the threat that it’s posing to the region and the implicit threat to the global economy as leverage on the US president.

We are talking about a regime that has long been fond of the idea of martyrdom. Is it a reach to suggest that might be a factor underpinning its strategy? Do they care whether this goes well for them?

There’s a possible case that the former supreme leader himself didn’t hide away because he was prepared to accept martyrdom. For the regime it’s not so much martyrdom as an existential struggle. The idea is that if they surrender now, they will be picked off later. They’re absolutely convinced of that. They don’t trust Trump, they don’t trust Israel. They’re worried about popular pressure from the protests in January. Hence why this conflict turned out so differently from the war in June 2025. It’s not: ‘we must destroy ourselves as martyrs’. It’s: ‘if we don’t fight now, we will be destroyed anyway, without a way to push back’.

The US is likely [feeling] disheartened that the populist revolt they envisioned didn’t materialise. Do we know how Iranian public opinion, with all due acknowledgement that it is not a monolith, will respond to a hereditary supreme leader, given that the revolution of 1979 was waged to overthrow a dynasty?

We know very little about Iranian public opinion at this point, simply because anybody who takes the initiative to reach out past the internet blackout is already expressing some kind of ideological view. What we can say is that there will probably be some pushback among the base against the hereditary principle but not as much as would have been the case before the war. This pushes back at the US, and particularly against Donald Trump’s statement that he didn’t want [Mojtaba Khamenei] to succeed. The hereditary principle will be something else to push back at them with but it won’t fundamentally change their views.

Listen to the full conversation on ‘The Briefing’ on Monocle Radio.

More stories about the war in Iran:

– Meet the Kurdish peshmerga fighters waiting to enter the war against Iran

– The view from the Strait of Hormuz: Ground zero for Iran’s war on global commerce

– With Bahrain and Dubai under fire, Riyadh has emerged as the Gulf’s unlikely refuge