On his first full working day as the Netherlands’ youngest prime minister, Rob Jetten did not reach for the phone to call Brussels, Berlin or Paris. He called Kyiv. The conversation with Volodymyr Zelensky, brief but pointed, carried a message that needed no elaboration: whatever had recently happened in The Hague – the collapse of a populist experiment, 11 months of dysfunction, three governments in four years – Dutch support for Ukraine was not among the casualties. It was a well-chosen opening move and it showed something about Jetten that his predecessor rarely managed to convey: a sense of where he stands.

A different wind is blowing through The Hague. Whether it builds into momentum or fades into the familiar fog of coalition politics will define the coming months, not only for the Dutch but for a continent searching for credible, pro-European leadership. This feels less like a revolution and more like a recalibration.

Jetten, the social-liberal D66 party’s 38-year-old leader, is many things his predecessor was not. He is articulate, telegenic and, crucially, competent. A low bar, given that Dick Schoof was widely regarded, by allies and adversaries alike, as the most inept premier that the Netherlands has produced in living memory. Schoof’s populist experiment collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions, leaving Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV party diminished and divided. Following January’s parliamentary split into two rival factions, it is considerably defanged.

Yet the nagging irony of Jetten’s opening days is this: at a moment when Europe’s leadership constellation looks tarnished, with Merz, Macron and Meloni locked in a triangular dispute over the continent’s direction, the new Dutch premier is reportedly not travelling to Brussels and Paris until next week. For a politician who could plausibly position himself as a fresh pro-European voice, his hesitation reads like a missed opportunity.

At home the parliamentary arithmetic is sobering. The coalition commands just 66 of the 150 seats in the Tweede Kamer, the first minority government since 1939. Every significant piece of legislation will require the cultivation of ad hoc majorities from an opposition that has already signalled its intention to extract its price. This is not necessarily fatal; minority governments in Scandinavia have produced durable policies. But it demands political dexterity and Dutch coalition culture does not always reward boldness. The Netherlands – just like the rest of Europe – needs an injection of optimism and pro-business policy.

The governing challenges are formidable. The country faces a housing crisis of near-structural severity, a shortage so acute that urban planners speak of it in the same breath as climate adaptation: systemic, expensive and generational. The target of 100,000 new homes a year remains politically popular and practically elusive. Defence spending must rise sharply to meet Nato obligations. Infrastructure investment has been deferred for too long. All of this against a fiscal backdrop demanding restraint, despite the Netherlands remaining one of Europe’s more robust economies. Austerity and ambition make uneasy partners.

But Jetten’s broader significance should not be understated. A pro-European, pro-business, pro-Nato and socially liberal party has emerged – narrowly but decisively – as the largest in the Netherlands after a populist implosion. Across Europe this is being read as a recipe for reversal. If his call to Kyiv was about certainty abroad, the real uncertainty lies at home. Governing by minority demands stamina and if Jetten possesses it, then it’s Europe’s gain as well as that of the Dutch.

Stefan de Vries is an Amsterdam-based journalist.

We’re not ones for kicking folks when they’re down but things seem to be going from bad to worse for Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk. The drugmaker was once Europe’s most valuable company thanks to its discovery of obesity treatment Wegovy. But since peaking in 2024, its share price has fallen by roughly two-thirds amid disappointing clinical trial results, a poorly handled change of CEO and mass redundancies. Increasing competition and a lack of control over copycat drugs produced by US compounders have also hit hard.

It was hoped that the approval of an oral version of Wegovy in December would help to pull the company out of its slump. Instead, more disappointment has followed. Novo’s next would-be breakthrough weight-loss treatment, Cagrisema, appears underwhelming, even before launch. A study published yesterday found it to be less effective than rival Eli Lilly’s Tirzepatide. Novo had been counting on Cagrisema to reignite growth in a market already unsettled by concerns over side effects and the tendency for users to regain weight after stopping treatment. By now, shareholders must be hoping for a miracle.

After announcing 9,000 redundancies in September in response to lowered growth forecasts and a rapidly changing market. The company’s decline has been as swift as it has been surprising – to the Danes, at least.

By late 2023, sales of Novo’s diabetes drug, Ozempic, and its obesity treatment derivative, Wegovy, helped it become Europe’s largest company by market capitalisation. The first shock to what had been a sky-rocketing share price appeared in December 2024 with disappointing trial results of its next-gen obesity drug, Cagrisema. Meanwhile, the company was failing to meet demand, allowing rivals such as US-based Eli Lilly to increase their market shares. Growing online sales of counterfeit drugs compounded the challenges.

In late 2024, I visited Novo to interview Dr Lotte Knudsen, who leads the team whose research resulted in Ozempic. She was deeply impressive but I did sense an odd complacency about Novo’s production bottlenecks, their rivals and those aforementioned counterfeiters. The prevailing attitude seemed to be that “there are plenty of fat people in the world to go round.”

A few months later, at a get-together at an ambassador’s residence here in Copenhagen, I shared my concerns for Novo with a former executive of the company. She grabbed my arm as if she were an escapee from a cult: “Yes, exactly,” she said. “But it’s worse than that.” She described an organisation that was reticent to the point of self-harm when it came to seeking leadership from outside of a small cabal of top-level executives, all of whom were Danish.

On one hand, it seems fair that Danish companies are led by Danes. After all, the Danes’ confident leadership style is sought after in neighbouring Sweden, which is often hamstrung by consensus-driven decision making. But Danish CEOs are a strikingly homogenous bunch: predominantly males in their 50s, they inhabit the same wealthy enclave on the coast north of Copenhagen and even have a de facto uniform: a navy, two-button suit, with no tie. (It’s perhaps a trivial point but their cultural hinterland seems mostly limited to cycling and running.) Mads Nipper, the former CEO of crisis-hit Danish energy company Ørsted, is a classic example. His replacement, Rasmus Errboe, is a mere 46 years old – but he too was promoted from within the company.

Here is the issue, though: Novo Nordisk is a profit-driven company but some of those profits (notably dividends) end up in a philanthropic foundation. Dr Knudsen proclaimed herself “a proud socialist”. Altruism and philanthropy are of course deeply admirable but one sometimes wonders if Danes are hungry or ruthless enough for the global corporate environment.

In May of last year, Novo’s board sacked its own identikit Danish CEO, Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen, without having a replacement lined up. Interviewed on Danish television on the day of his firing, he seemed in shock but assured the interviewer that he would handle his defenestration like “a professional” (odd that needed saying). Jørgensen maintained his belief that the US authorities would crack down on counterfeit products. To me this seemed somewhat delusional, given the same US authorities were hurling tariffs at the world, threatening Danish interests in Greenland and then cancelled Ørsted’s crucial Rhode Island wind-farm project, which resulted in the state-owned energy company’s share price plummeting to a record low.

Novo Nordisk finally appointed Jørgensen’s replacement – Mike Doustdar, an Austrian-Iranian company vice-president, is the first non-Dane to run Novo since it was founded in 1923. Although he sometimes wears a tie, things don’t seem to be looking up.

This article was originally published on 12 September 2025 and was updated on 24 February 2026 to reflect the result of the Cagrisema study.

Michael Booth is Monocle’s Copenhagen correspondent. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today. To read Booth’s interview with the quiet scientist behind Ozempic, click here.

From Tuesday 24 February, Stone Island settles into The Monocle Shop in London for a two-week residency. Our Marylebone address will present an edit of the Ghost spring/summer 2026 sub-collection – as featured in Monocle’s February issue – with a custom window installation.

Stone Island’s Ghost collection is where the label’s fabric research comes to a point. Leather, suede and linen do the heavy lifting in this edition, each chosen for its unique attributes and rendered in a tight seasonal palette. Rooted in the idea of camouflage, Ghost looks to keep to a single hue from collar to cuff – even the brand’s iconic compass has been tonally reworked.

This season’s designs nods to Californian workwear; a standout sand-coloured suede jacket references the tone of traditional worker’s gloves. Elsewhere, a blue linen field jacket is bonded to an internal cotton layer, giving the piece structure while keeping the softness that makes linen such an easy summer companion. Careful construction across the edit turns familiar materials into items with understated yet precise detailing.

Staged against stone and open skies in rural Sicily, Monocle’s February photoshoot sharpened the collection’s tonal discipline and heightened its interplay of texture and light. Now the pieces arrive in London for closer inspection. Drop by before 10 March to see how they look – and feel – in person.

The Monocle Shop, London

34 Chiltern Street

London W1U 7QH

The concentration of US firepower around Iran now looks less like signalling and more like sequencing. For months, tensions between Washington and Tehran have simmered over nuclear thresholds, regional proxies and the careful choreography of red lines repeatedly tested but never quite crossed. What distinguishes this moment is not the rhetoric but the hardware. The assets now in play suggest that the US is no longer merely demonstrating resolve – it’s positioning itself for choice.

Since late January, a carrier strike group built around the USS Abraham Lincoln has been operating in the region – substantial enough on its own. But increasingly, there are more. The USS Gerald R Ford, the largest aircraft carrier in the world, has been positioned at the mouth of the Mediterranean and is moving eastward. Two carrier strike groups – one in the Arabian Sea and one in the Mediterranean – would give Washington overlapping arcs of airpower and cruise-missile reach. Around them sit at least 11 air-defence destroyers, three littoral combat ships and two to three attack submarines equipped with Tomahawk missiles. That is the naval element of the equation: visible, mobile and readied to project force.

The second part is both logistical and defensive. In the past month, more than 250 US military airlift flights have landed in the Middle East and surrounding hubs, moving large equipment and air-defence assets. Over the past two weeks, C-17 Globemasters and C-5 Super Galaxies – the US Air Force’s broad-shouldered, heavy-lifting aircraft – have been shuttling equipment into American facilities across the Gulf. The likely purpose is straightforward: harden bases against retaliation before any strike begins.

At Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, aircraft numbers have climbed from 16 to 29, including seven C-17s and 17 KC-135 refuelling tankers. Unlike those behemoth aircraft carriers, tankers are a more subtle indicator of intent. They extend range, loosen political constraints and allow aircraft to operate from further afield if host nations hesitate.

The final element is geographical. Flight tracking over the past week shows multiple waves of KC-135 tankers moving from the US via the UK to bases in Greece and Bulgaria. Six were tracked on 16 February; another 10 followed on 18 February, staging through the UK before heading southeast. The message is implicit. Even if access to some Middle Eastern bases becomes politically fraught, aircraft could operate from southern Europe, with tankers bridging the distance. The movements of US assets confirm that Washington is deliberately widening its geography.

Overlaying all the traffic and hardware is command and control. Six E-3 Sentry AWACS aircraft – the distinctive radar-domed platforms that map the battlefield in real time – are now in theatre. With sufficient tankers and airborne early warning cover, a large-scale air campaign moves beyond theory and threat.

Diplomacy, for now, is running in parallel. A fresh round of US-Iran talks is scheduled in Geneva this week, with Oman mediating. The timing is awkward; negotiations are resuming just as the military appears closest to operational readiness. Taken together, the naval mass, reinforced air defences, tanker bridge to Europe and expanded airborne command assets suggest that Washington could sustain a significant campaign. Today’s US administration, perhaps more than others, is capable of tilting leverage toward action. The open question is not capability, it is intent. Hopefully this military posturing is enough to lure Tehran to the table and strike a deal.

Inzamam Rashid is Monocle’s Gulf correspondent. For more opinion, analysis and insight, subscribe to Monocle today.

The autumn/winter edition of London Fashion Week concluded last night with British luxury fashion house Burberry showing its collection at Old Billingsgate – a former Victorian fish-market-turned-events-space. Providing the soundtrack to the evening was British DJ, producer and radio presenter Benji B, who has collaborated with the brand since Daniel Lee was appointed chief creative director in September 2022. “When I see feet tapping at a show I know that I’ve done a good job,” he tells Monocle. We hear from Benji B about this season’s inspiration and why the UK’s music scene is a soft-power tool.

How does this season’s show soundtrack represent an evolution of your collaboration with Burberry?

With Daniel at Burberry, I wanted to develop a story that celebrates a single artist – and British music – each time. I think of the shows as a box set. Each episode makes sense on its own but if you zoom out and look at them all together, you’ll see the arc of a story. [The inspiration] was a cocktail of different things that put me into a pocket of sound. This season’s strong themes were London at night and femininity. All the planets eventually settle into orbit but generally it’s a combination of seeing what the expression of the set is, as well as the initial mood boards with Daniel and the collection itself. We often go through a few ideas and options of different sequences and artists before landing on the final selection. Obviously, Daniel has the big picture. It’s always a back-and-forth process.

The UK’s music scene is an incredible soft-power tool for Britain. Which heritage elements do you tap into for a project like this?

It’s very easy to focus on the elements that are celebrated. It’s important to note that it doesn’t come from some overly patriotic standpoint but how beautiful, varied and diverse the contribution of British music is to the world. It doesn’t have to be musical heritage either – it can be contemporary. I’ve used songs by Dean Blunt and then Amy Winehouse. Last season in Hyde Park we celebrated Black Sabbath and Ozzy Osbourne because we have always been fans of the song ‘Planet Caravan’. I’m very proud to say that tonight’s artist, FKA Twigs, is someone who is very contemporary but sits in the same space as all those people.

Music plays a crucial part in setting the tone and the mood of a fashion show. How do you hope people feel when they watch something that you’ve created the soundtrack for?

I hope that people can leave inspired. You don’t want the music to distract from the fashion. We’re supporting the work of a designer that is showing on the runway. But we don’t want it to just be background noise – it has to have dynamic range. It’s amazing what sound can achieve in 12 to 15 minutes. What I love about FKA Twigs is that her music has that dynamic range across different albums and eras. I hope that people experience a journey and find a soundtrack that feels contemporary. What we often take away from runway shows is the last thing that we experience, so I want people to leave feeling energised.

The biggest exhibition of artist Rose Wylie’s work to date opens on 28 February at London’s Royal Academy. Rose Wylie: The Picture Comes First brings together some of her most enduring paintings, alongside new work. Wylie is known for her bright, bold canvases, which reference ancient history, popular culture and her own life.

While Wylie was preparing for the exhibition last year, Monocle visited her studio in Kent to get a sneak peek at some of her paintings, as well as works in progress. Read on for Monocle’s profile of the sprightly Wylie and a behind-the-scenes look at her famous (and famously messy) studio. Rose Wylie: The Picture Comes First is on at the Royal Academy from 28 February to 19 April.

When a particularly big globule of paint falls off Rose Wylie’s brush, she’ll simply cover it with a sheet of newspaper to stop it getting on her shoes. “I’m not a precious worker,” she says as we stand in her studio. A soft layer of newspaper carpets the floor, paintbrushes stick out of cans stacked on chairs and colourful splatters obscure the skirting board. Wylie’s unruly garden has crept up the side of the house and into this first-floor room – a jasmine plant pushes through a window in one corner. “Mostly you’re criticised if you don’t tidy up,” she says. “But if you get through a certain threshold, it becomes iconic.”

Wylie’s artistic training went unused for years while she raised her family but, since returning to painting in her forties, she has become a critical and commercial darling of the art world. She is currently working on a painting that features a large, “nonchalant” skeleton. It will appear in her upcoming exhibition at London’s Royal Academy in early 2026, her biggest show to date.

Wylie’s bold canvases often combine text and figures from history, mythology or contemporary pop culture. And while Wylie’s process can be messy, she is exacting about her practice, regularly working late into the night wrestling with a painting. “Often it’s horrible, slimy, trite, pedestrian,” she says. “There are 100 things that can go wrong, particularly with faces, and then, for some odd reason, suddenly it’s alright.”

Born: 1934

Breakthrough moment: Women to Watch exhibition in Washington (2010)

Elected to the Royal Academy: 2014

This article was originally published 15 October 2025 and was updated on 23 February 2026 to reflect Wylie’s show at the Royal Academy London.

On the wall of Ramesh Shukla’s Dubai home hangs a 50-dirham note in a simple frame. Visitors often assume that it is there for the currency’s novelty value. It is not. The note carries his photograph of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan signing the Federation agreement in 1971 – an image so embedded in the UAE’s psyche that it circulates daily in wallets and tills. When the design was first issued, his son Neel tells me, Shukla went around handing out crisp notes to friends and strangers alike. “He was giving out free 50-dirham notes to people, proudly showing off his work.”

It is an endearing detail but also a revealing one. For a man who never chased a salary, never invoiced a ruler and never built a property portfolio, that small rectangle of polymer was proof of something more enduring than wealth.

I meet Neel and his mother, Taru, in the family apartment where Shukla lived for the past 20 years. The walls are dense with art – not only the black-and-white photographs that documented the rise of a country but paintings he later made of those same moments. History, then memory, then reinterpretation. There are pictures of Bill Clinton, a youthful King Charles III, Gulf rulers, Bollywood stars. “He’s seen it all,” Neel says. A tour of the house reveals thousands of prints and canvases – enough to fill a museum easily. And yet the most interesting thing about Shukla is not his proximity to royalty. It’s his position behind them.

He arrived from Gujarat by boat in the late 1960s with hardly any cash and a camera. He left India not as a businessman or engineer – the archetypal Gulf migrant – but as an artist. In Bombay, he had supplied photographs to newspapers. “He never got any job, never took a salary”, Taru tells me. “Whatever he photographed, they’d give some money”. It was a precarious existence even then. In the Emirates, it would be more so.

Within days of landing he was photographing a camel race attended by local rulers. When he showed the prints to Sheikh Zayed, something shifted. “Eye-to-eye connection”, Taru says, locking her fingers together to illustrate the point. Zayed recognised the talent and told him to stay.

From that point on, Shukla became a constant, crouched presence at the birth of a nation. But he did not experience it as history. “He just saw human beings with incredible charisma,” Neel insists. The famous Federation photograph was not taken with a sense of destiny but with technical obsession. He focused on the nib of the pen; Taru developed the negative at home in improvised trays. “If you give too much time, it’s overexposed; less time, it’s underdeveloped”, she says. The stakes felt personal: “Our life will be spoiled”.

The image would later become the visual shorthand for unity. At the time, it was simply the best frame he could make.

It’s tempting to romanticise the title “royal photographer” but it risks obscuring a more telling narrative. Shukla was an Indian immigrant who recorded the ascent of Dubai and the UAE from the shadows. His Rolleiflex sat low at waist level; his lens looking up at leaders who were building a state. The symbolism is almost too neat. Millions of expatriates – Indian, Pakistani, Filipino and beyond – have constructed the Emirates physically and economically. Shukla constructed it visually. All in their own way were present but peripheral to the official story.

“‘My bank balance doesn’t dictate who I am’”, Neel recalls his father saying. “‘My work is my bank balance’”. While others bought land, he bought film. While contemporaries moved into commerce, he doubled down on craft. Even as he gained extraordinary access – travelling with Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum on hunting trips, photographing leaders at home and abroad – he never leveraged it into business. “He never said, ‘Give me money’”, Neel says. “There was no ‘give me’”.

That choice came at a cost. The life of an artist in a boomtown is rarely straightforward. “It was very hard, very challenging”, Neel says. “As an artist, there’s no progression”. Yet perhaps that was precisely why the rulers trusted him. He was not there to extract but to observe.

There is a story Taru tells about Sheikh Mohammed asking her husband how many girlfriends he had. “Twenty,” Shukla replied, referring to his cameras. It is a line that captures his singularity. He loved equipment, light, composition – not mere accumulation.

In the days since his death, tributes have flowed from across the Emirates, including from Dubai’s Crown Prince. They recognise a man who dedicated six decades to documenting the country’s transformation. But perhaps his deeper legacy lies in what his vantage point represents.

To look at modern Dubai is to see skyline and spectacle. To look at it through Shukla’s archive is to see something quieter – leaders squatting on sand before there were chairs, handwritten documents before ministries, desert hunts before highways. His photographs anchor a narrative that might otherwise drift into myth.

Neel, dressed in a black kandura – a subtle signal that this is home – speaks about stewardship now. The family has resisted commercialising the archive. “We want this to have a meaning,” he says. It is not just a trove of images but a record of immigrant contribution rendered visible.

Shukla died with a camera nearby and his signature Panama hat on his head. Even in his final days he was signing prints as part of a vast project for the UAE’s president. “‘Son, this is what I live for,’” Neel recalls him saying.

In the end the most striking image is not the one on the 50-dirham note. It is the idea of an Indian man, waist-level camera in hand, steadying his frame while history unfolds inches away. He rarely appears in the photographs that define the UAE. But without him and without those like him, the picture would be incomplete.

Inzamam Rashid is Monocle’s Gulf correspondent. For more from Rashid, click here.

With persistent heavy showers drenching much of northern Italy earlier this month, Milan was not feeling particularly optimistic ahead of the Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony. Reporters spoke of a spirit split across the Lombard capital and the Alpine towns hosting events: enthusiasm was high in the towns, while Milan plodded along as if the eyes of the world were elsewhere. A little more than two weeks on, the Olympic torch has been extinguished but the clouds over Milan have finally lifted, revealing a city swinging with cranes and a sense of self-assurance.

“We haven’t felt this way since Expo 2015,” Monica Diluca from Università degli Studi di Milano tells Monocle as we walk through Milano Innovation District. Diluca pauses amid piles of rubble around the Decumano (the principal pedestrian boulevard) to gesture at a marked point: “This is here to remind us of the exact moment a decision was made to stop demolishing the original buildings from 2015.” It signifies a change in the city’s attitude: a shift towards renewal and long-term urban strategy.

“Milan is getting a new identity,” says Patricia Viel, co-founder of ACPV Architects, a firm that is responsible for transforming an entire business district on the city’s southern edge. “Modernity is very much embedded in the aesthetics of its evolution,” she adds. “[Milan has a] growing ability to attract international champions in the economic world”. Those “international champions” have made the Lombard capital one of Europe’s most multicultural cities; foreign residents now exceed 20 per cent.

The city’s global outlook has only broadened with the arrival of the Winter Olympics. “The Expo was a moment [when] we could restart a design season with architects from all over the world,” says Manfredi Catella, CEO of Coima, one of Italy’s most influential property-development and investment groups. “It marked the beginning of a transition for the city, which is continuing with the success of the Games.”

By hosting two global events, the city has proved to itself that – unlike neighbouring metropolises – it is able to deliver successful megaprojects with style and confidence. It’s certainly true for development; there are few other European cities with such a scale of brownfields or industrial sites that can be repurposed. Italy is not known for bureaucratic efficiency, though Milan has demonstrated a pragmatic performance on the world stage.

This edition of the Winter Games was designed with a focus on sustainability. This is perhaps most visible in the sprawling Olympic Village, which was slotted into the former rail yards at Porta Romana and will soon become student accommodation.

The feeling of Milan quietly looking over its shoulder at Rome is over. It has successfully crafted its own identity, one that embraces both its history and capacity for reinvention. Just take a ride on its near-century‑old streetcars adorned in Moncler advertising. People want to be here and they also want to be associated with the city’s renewed sense of purpose. After the last curling stone is packed up and the snowpants are hung to dry, Milan will have shown that it is now less self-critical, more confident and ruthlessly efficient.

Tom Webb is Monocle’s deputy head of radio. For more from Milan, check out our dedicated City Guide.

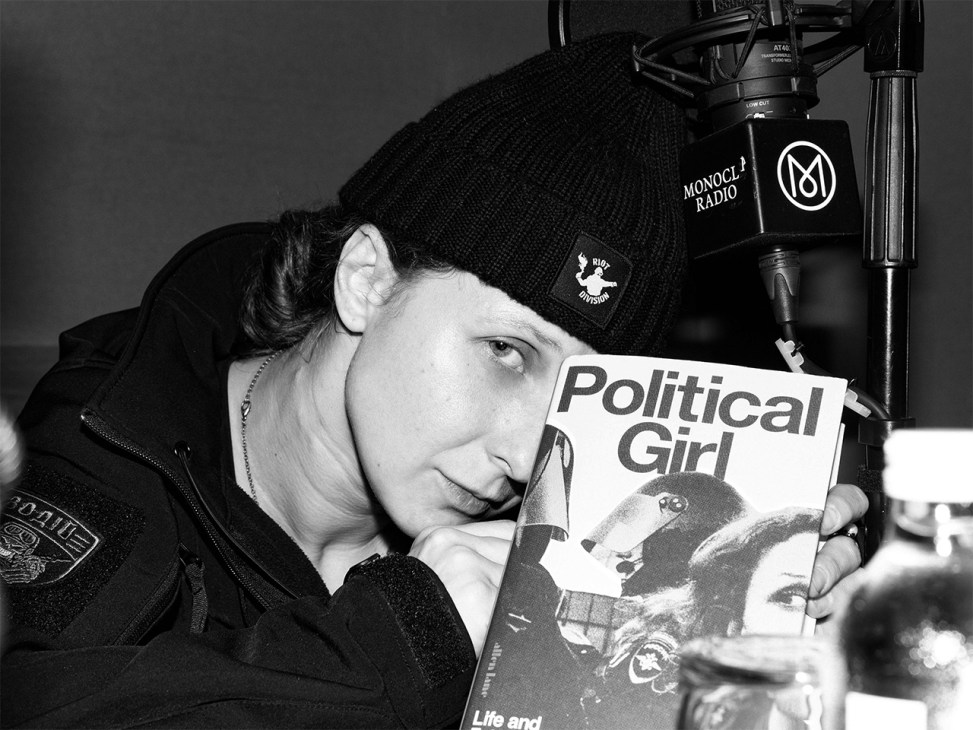

Maria Alyokhina is a Russian political activist known for her work as a member of Pussy Riot, the feminist protest group. The collective was thrust into the global spotlight in 2012 after an audacious performance inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

Alyokhina has just released Political Girl: Life and Fate in Russia, which details intimate accounts of her work as an activist between 2014 to 2022. In the book, she recounts her near two-year-long imprisonment in a penal colony and reflects on the Kremlin’s suppression of LGBTQ+ rights in Russia. Here, Monocle’s Georgina Godwin speaks to Aloykhina about the harsh realities of living under Vladimir Putin’s regime, the activist’s support for those still imprisoned and her hopes for the future of her country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to it in full by tuning in to Meet The Writers on Monocle Radio.

When did you realise that art could be used as a weapon?

I was asked to film an activist group rehearsing an action they were planning. At first, I didn’t know what ‘action’ was but basically, it is protest in the form of art. They were preparing an action inside a courtroom where the state was prosecuting two art curators for their exhibition about religion. That was when I first realised that the state can prosecute people for putting on exhibitions. The [curators] didn’t receive a prison term but they were criminally prosecuted.

How did the group Pussy Riot come together? And what did you think about the consequences of your work?

The time between the end of 2011 and the beginning of 2012 was one of hope. There was a large movement in Russia protesting Putin’s third presidency and we were part of that. There were zero artists or activists in prison at that time. My goal was to show through our actions how Putin was shutting down freedoms. We decided to protest the church promoting Putin and I was surprised when they opened a criminal case. When I was taken by the police, I left my apartment [after] telling my son that I would come back tomorrow. I came back two years later.

The book starts at the point at which you’re leaving the penal colony. What was it like inside?

In Russia, we have a post-Gulag system during pre-trial and trial investigations where you are held in a jail cell. After the sentencing they transport you to a penal colony, which is a number of barracks where 100 women sleep together in a room with just two or three toilets, no hot water, no normal food and a [single] fridge. Another part of the colony is a working zone – a factory where prisoners sew uniforms for the police and Russian army.

Russia today has thousands of political prisoners, many of them unknown. What do you think that readers [of your book] need to understand about them?

Now, with the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine], anyone can be killed and people go to prison for 20, 25, 29 years for just being against this fucking war that Putin started.

It’s clear now, after Putin killed [Russian opposition leader] Alexei Navalny, that anyone can be killed at any moment. Inside the country, there is a network of concentration camps. They put people from the occupied territories into these buildings and hold them there incommunicado, without status. They are not officially prosecuted but this is happening right now to 20,000, 30,000 people. Lawyers I know work with these [prisoners] and they say that they are being tortured. Sometimes [the government] opens official criminal cases [against these people] and transport them to prisons. There, they might speak to other prisoners about what they have been through. That’s how information about these places has become known.

Further reading?

– Russian opposition activist Vladimir Kara-Murza on surviving Putin’s gulag – and the moment when he thought he would be executed

– Ukraine’s women have the skills needed on the battlefield

– Are Poland’s efforts to bolster its defences enough to deter Russia?

What makes you proud of your country? National pride is among the trickiest of subjects in today’s political atmosphere: show too much and you’re liable to be labelled a nationalist; too little and you risk being seen as ungrateful. The sentiment is further complicated for countries with tortured pasts (or presents). While the complexity of national pride is not new, the tenor of its expression feels heightened today – outside of sporting events, that is.

But what is national pride, and what are the elements of a nation and its people that one might feel proud of? Washington-based Pew Research Center aimed to answer this question through a recent survey that asked 33,486 people across 25 countries for their take.

The query posed to respondents was left purposely open-ended, “to allow the uniqueness of different countries to shine through,” Laura Silver, a researcher at Pew, tells Monocle. Indonesians reported being proud of their spices, for example, while the Dutch took pride in their waterway management.

Some respondents weren’t proud of their nations. Hungarians showed strong partisan divides over their president, Viktor Orban, with some respondents highlighting him as a source of pride and others citing the leader as a reason for their lack of pride. “People are pretty frustrated with how politics is working in many countries,” says Richard Wike, director of global attitudes research at Pew.

While national politics often dominate headlines, they aren’t the only thing that make a country. There’s the government, sure, but a country is also composed of people with cultural heritage, language, food and many more facets besides. While the Swedes were particularly proud of their political system, many respondents opted to mention their nation’s people, rather than governments as a source of pride.

“In Argentina, for example, people often talked about their public being ‘united’,” says Silver. “In Brazil, people emphasised the welcoming nature of their public”. For others, handicrafts or honesty were notable traits. “Even when people emphasised their fellow citizens, they did it in unique, distinct terms,” Silvered continues.

The research revealed that some people think about pride on a national scale, while others considered it on a personal level. Family heritage and long ties to a nation, or diversity, arts, culture and food that get exported were all mentioned as points of pride. “People are proud of cultural things that they share with the rest of the world,” Wike says, adding that many citizens cited their countries’ Nobel Prize winners. “When people see their country recognised by the rest of the world for something, that’s a big source of pride.”

Monocle posed the question – what makes you feel proud of your country? – to a handful of our colleagues from some of the nations represented in the survey. Here is what they had to say.

Andrew Tuck, UK

Key survey stat: 29 per cent of Brits said they were not proud, more than any other nation.

“People in the UK have always wrestled with it. They’ve never been sure that they can stand behind the flag, as many Americans would do. We’ve had essentially four nations packed into this union who are all tugging at their own identities. But I do think you have key moments, a challenge or a moment of victory.”

Hannah Girst, Germany

Key survey stat: Germans are one of the few nations whose political system is a top source of pride (36 per cent) as well as their economy (18 per cent), praising its strength and stability.

“What makes me proud of Germany is the teamwork. You can see it in moments such as the World Cup, especially in 2014: there’s something very German about staying calm under pressure and delivering when it matters most. I’m also proud of Germany’s commitment to sustainability. I love the way my family in Germany recycles and I wish more countries would do the same.”

Sara Bencze, Hungary

Key survey stat: Hungarians are among the most likely of the countries surveyed to emphasise their current leadership (13 per cent) as a source of pride – but also to say that they’re not proud of their country (23 per cent).

“Hands down the country’s intellectual output across both science and the arts. We have quite a few Nobel Prize-winning contributions to science and literature, filmmakers who have revolutionised cinema, and even the underground music and arts scenes, with grassroots bands performing internationally.”

Ryuma Takahashi, Japan

Key survey stat: 41 per cent of the Japanese cite the people themselves as a source of pride and 18 per cent emphasise “peace” and “safety”, more than most other countries.

“Japan is often described as a homogenous country but I’m proud of its diversity and its soft power. When you travel around Japan, you will find different climates, languages, food and local cultures. We have unique comedy, music, games, anime and films.”

Nic Monisse, Australia

Key survey stat: 25 per cent emphasise the “mateship” they feel with other Australians as well as how they “lend a hand” in times of need.

“It’s friendship, more or less: looking out for your mates. It’s hugely important; we learn about it at school. It’s embedded in everything from the Anzac Day spirit (a key part of our national identity was built off of a military failure, which says a lot about the country) to our obsession with sport and a laid-back attitude.”

Chiara Rimella, Italy

Key survey stat: Italians are particularly proud of their arts and culture (38 per cent), citing beautiful architecture and the Renaissance, and are among the most likely to cite their country’s food (18 per cent)

“We have a ministry for ‘Made in Italy’ and Italians, generally speaking, are very proud of Italy – with reason because there are plenty of things in our august history to be proud of. But it becomes a kind of national obsession sometimes, a weight of influence where you have all these grand riches from the past, and it can become hard to detach and really reflect on what the country is right now.”

Fernando Augusto Pacheco, Brazil

Key survey stat: A quarter of Brazilians say that they are proud of their people, describing them as welcoming and accepting, and highlighting the country’s positive social climate.

“I’m very proud of being Brazilian, maybe too much. But in a world as divisive as we’re living today, I think people are waking up to the importance of Brazil in society, because of our welcoming nature. Another word that comes to my mind when I think of Brazil is flexibility: whatever your religion or your sexuality, we live together. I’m definitely not saying that it’s a perfect country but the world needs more of that flexibility.”

Angelica Jopson, South Africa

Key survey stat: South Africans cite their country’s services (24 per cent) more than most nations, as well as housing, “social grants”, police and pensions.

“I have a strong sense of pride in the diversity of the country. A rainbow nation, as we call it, however imperfectly, has held its centre since the end of apartheid. We have 11 official languages, five of them in our national anthem and, for good measure, one of the world’s most colourful flags. Like a mad family, we might have internal divisions but we band together when it matters most.”