With persistent heavy showers drenching much of northern Italy earlier this month, Milan was not feeling particularly optimistic ahead of the Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony. Reporters spoke of a spirit split across the Lombard capital and the Alpine towns hosting events: enthusiasm was high in the towns, while Milan plodded along as if the eyes of the world were elsewhere. A little more than two weeks on, the Olympic torch has been extinguished but the clouds over Milan have finally lifted, revealing a city swinging with cranes and a sense of self-assurance.

“We haven’t felt this way since Expo 2015,” Monica Diluca from Università degli Studi di Milano tells Monocle as we walk through Milano Innovation District. Diluca pauses amid piles of rubble around the Decumano (the principal pedestrian boulevard) to gesture at a marked point: “This is here to remind us of the exact moment a decision was made to stop demolishing the original buildings from 2015.” It signifies a change in the city’s attitude: a shift towards renewal and long-term urban strategy.

“Milan is getting a new identity,” says Patricia Viel, co-founder of ACPV Architects, a firm that is responsible for transforming an entire business district on the city’s southern edge. “Modernity is very much embedded in the aesthetics of its evolution,” she adds. “[Milan has a] growing ability to attract international champions in the economic world”. Those “international champions” have made the Lombard capital one of Europe’s most multicultural cities; foreign residents now exceed 20 per cent.

The city’s global outlook has only broadened with the arrival of the Winter Olympics. “The Expo was a moment [when] we could restart a design season with architects from all over the world,” says Manfredi Catella, CEO of Coima, one of Italy’s most influential property-development and investment groups. “It marked the beginning of a transition for the city, which is continuing with the success of the Games.”

By hosting two global events, the city has proved to itself that – unlike neighbouring metropolises – it is able to deliver successful megaprojects with style and confidence. It’s certainly true for development; there are few other European cities with such a scale of brownfields or industrial sites that can be repurposed. Italy is not known for bureaucratic efficiency, though Milan has demonstrated a pragmatic performance on the world stage.

This edition of the Winter Games was designed with a focus on sustainability. This is perhaps most visible in the sprawling Olympic Village, which was slotted into the former rail yards at Porta Romana and will soon become student accommodation.

The feeling of Milan quietly looking over its shoulder at Rome is over. It has successfully crafted its own identity, one that embraces both its history and capacity for reinvention. Just take a ride on its near-century‑old streetcars adorned in Moncler advertising. People want to be here and they also want to be associated with the city’s renewed sense of purpose. After the last curling stone is packed up and the snowpants are hung to dry, Milan will have shown that it is now less self-critical, more confident and ruthlessly efficient.

Tom Webb is Monocle’s deputy head of radio. For more from Milan, check out our dedicated City Guide.

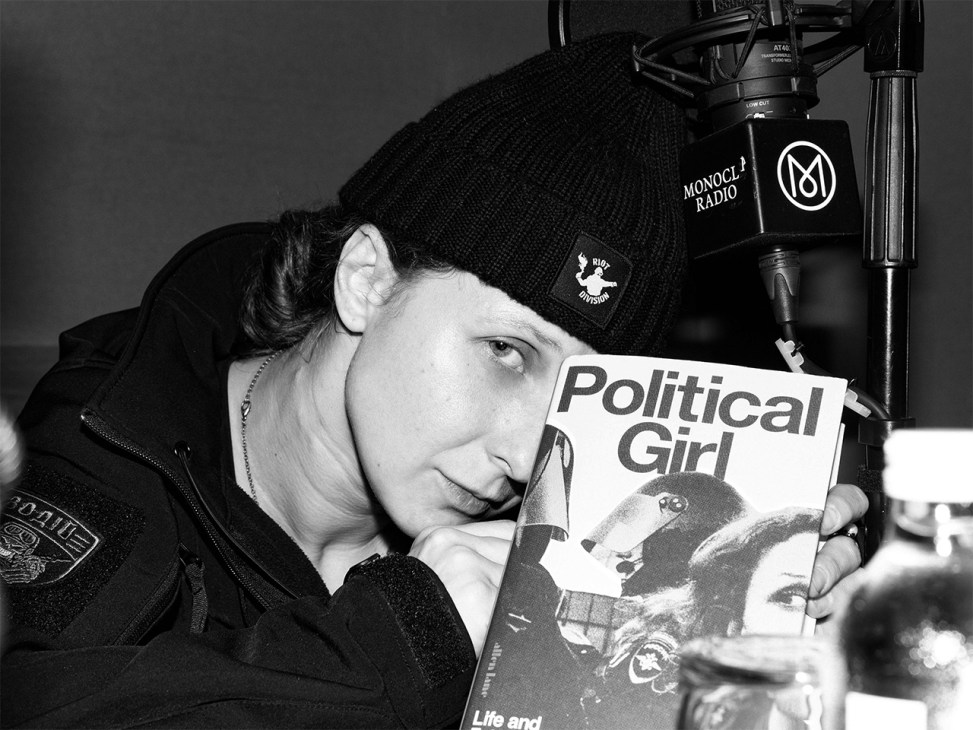

Maria Alyokhina is a Russian political activist known for her work as a member of Pussy Riot, the feminist protest group. The collective was thrust into the global spotlight in 2012 after an audacious performance inside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

Alyokhina has just released Political Girl: Life and Fate in Russia, which details intimate accounts of her work as an activist between 2014 to 2022. In the book, she recounts her near two-year-long imprisonment in a penal colony and reflects on the Kremlin’s suppression of LGBTQ+ rights in Russia. Here, Monocle’s Georgina Godwin speaks to Aloykhina about the harsh realities of living under Vladimir Putin’s regime, the activist’s support for those still imprisoned and her hopes for the future of her country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to it in full by tuning in to Meet The Writers on Monocle Radio.

When did you realise that art could be used as a weapon?

I was asked to film an activist group rehearsing an action they were planning. At first, I didn’t know what ‘action’ was but basically, it is protest in the form of art. They were preparing an action inside a courtroom where the state was prosecuting two art curators for their exhibition about religion. That was when I first realised that the state can prosecute people for putting on exhibitions. The [curators] didn’t receive a prison term but they were criminally prosecuted.

How did the group Pussy Riot come together? And what did you think about the consequences of your work?

The time between the end of 2011 and the beginning of 2012 was one of hope. There was a large movement in Russia protesting Putin’s third presidency and we were part of that. There were zero artists or activists in prison at that time. My goal was to show through our actions how Putin was shutting down freedoms. We decided to protest the church promoting Putin and I was surprised when they opened a criminal case. When I was taken by the police, I left my apartment [after] telling my son that I would come back tomorrow. I came back two years later.

The book starts at the point at which you’re leaving the penal colony. What was it like inside?

In Russia, we have a post-Gulag system during pre-trial and trial investigations where you are held in a jail cell. After the sentencing they transport you to a penal colony, which is a number of barracks where 100 women sleep together in a room with just two or three toilets, no hot water, no normal food and a [single] fridge. Another part of the colony is a working zone – a factory where prisoners sew uniforms for the police and Russian army.

Russia today has thousands of political prisoners, many of them unknown. What do you think that readers [of your book] need to understand about them?

Now, with the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine], anyone can be killed and people go to prison for 20, 25, 29 years for just being against this fucking war that Putin started.

It’s clear now, after Putin killed [Russian opposition leader] Alexei Navalny, that anyone can be killed at any moment. Inside the country, there is a network of concentration camps. They put people from the occupied territories into these buildings and hold them there incommunicado, without status. They are not officially prosecuted but this is happening right now to 20,000, 30,000 people. Lawyers I know work with these [prisoners] and they say that they are being tortured. Sometimes [the government] opens official criminal cases [against these people] and transport them to prisons. There, they might speak to other prisoners about what they have been through. That’s how information about these places has become known.

Further reading?

– Russian opposition activist Vladimir Kara-Murza on surviving Putin’s gulag – and the moment when he thought he would be executed

– Ukraine’s women have the skills needed on the battlefield

– Are Poland’s efforts to bolster its defences enough to deter Russia?

What makes you proud of your country? National pride is among the trickiest of subjects in today’s political atmosphere: show too much and you’re liable to be labelled a nationalist; too little and you risk being seen as ungrateful. The sentiment is further complicated for countries with tortured pasts (or presents). While the complexity of national pride is not new, the tenor of its expression feels heightened today – outside of sporting events, that is.

But what is national pride, and what are the elements of a nation and its people that one might feel proud of? Washington-based Pew Research Center aimed to answer this question through a recent survey that asked 33,486 people across 25 countries for their take.

The query posed to respondents was left purposely open-ended, “to allow the uniqueness of different countries to shine through,” Laura Silver, a researcher at Pew, tells Monocle. Indonesians reported being proud of their spices, for example, while the Dutch took pride in their waterway management.

Some respondents weren’t proud of their nations. Hungarians showed strong partisan divides over their president, Viktor Orban, with some respondents highlighting him as a source of pride and others citing the leader as a reason for their lack of pride. “People are pretty frustrated with how politics is working in many countries,” says Richard Wike, director of global attitudes research at Pew.

While national politics often dominate headlines, they aren’t the only thing that make a country. There’s the government, sure, but a country is also composed of people with cultural heritage, language, food and many more facets besides. While the Swedes were particularly proud of their political system, many respondents opted to mention their nation’s people, rather than governments as a source of pride.

“In Argentina, for example, people often talked about their public being ‘united’,” says Silver. “In Brazil, people emphasised the welcoming nature of their public”. For others, handicrafts or honesty were notable traits. “Even when people emphasised their fellow citizens, they did it in unique, distinct terms,” Silvered continues.

The research revealed that some people think about pride on a national scale, while others considered it on a personal level. Family heritage and long ties to a nation, or diversity, arts, culture and food that get exported were all mentioned as points of pride. “People are proud of cultural things that they share with the rest of the world,” Wike says, adding that many citizens cited their countries’ Nobel Prize winners. “When people see their country recognised by the rest of the world for something, that’s a big source of pride.”

Monocle posed the question – what makes you feel proud of your country? – to a handful of our colleagues from some of the nations represented in the survey. Here is what they had to say.

Andrew Tuck, UK

Key survey stat: 29 per cent of Brits said they were not proud, more than any other nation.

“People in the UK have always wrestled with it. They’ve never been sure that they can stand behind the flag, as many Americans would do. We’ve had essentially four nations packed into this union who are all tugging at their own identities. But I do think you have key moments, a challenge or a moment of victory.”

Hannah Girst, Germany

Key survey stat: Germans are one of the few nations whose political system is a top source of pride (36 per cent) as well as their economy (18 per cent), praising its strength and stability.

“What makes me proud of Germany is the teamwork. You can see it in moments such as the World Cup, especially in 2014: there’s something very German about staying calm under pressure and delivering when it matters most. I’m also proud of Germany’s commitment to sustainability. I love the way my family in Germany recycles and I wish more countries would do the same.”

Sara Bencze, Hungary

Key survey stat: Hungarians are among the most likely of the countries surveyed to emphasise their current leadership (13 per cent) as a source of pride – but also to say that they’re not proud of their country (23 per cent).

“Hands down the country’s intellectual output across both science and the arts. We have quite a few Nobel Prize-winning contributions to science and literature, filmmakers who have revolutionised cinema, and even the underground music and arts scenes, with grassroots bands performing internationally.”

Ryuma Takahashi, Japan

Key survey stat: 41 per cent of the Japanese cite the people themselves as a source of pride and 18 per cent emphasise “peace” and “safety”, more than most other countries.

“Japan is often described as a homogenous country but I’m proud of its diversity and its soft power. When you travel around Japan, you will find different climates, languages, food and local cultures. We have unique comedy, music, games, anime and films.”

Nic Monisse, Australia

Key survey stat: 25 per cent emphasise the “mateship” they feel with other Australians as well as how they “lend a hand” in times of need.

“It’s friendship, more or less: looking out for your mates. It’s hugely important; we learn about it at school. It’s embedded in everything from the Anzac Day spirit (a key part of our national identity was built off of a military failure, which says a lot about the country) to our obsession with sport and a laid-back attitude.”

Chiara Rimella, Italy

Key survey stat: Italians are particularly proud of their arts and culture (38 per cent), citing beautiful architecture and the Renaissance, and are among the most likely to cite their country’s food (18 per cent)

“We have a ministry for ‘Made in Italy’ and Italians, generally speaking, are very proud of Italy – with reason because there are plenty of things in our august history to be proud of. But it becomes a kind of national obsession sometimes, a weight of influence where you have all these grand riches from the past, and it can become hard to detach and really reflect on what the country is right now.”

Fernando Augusto Pacheco, Brazil

Key survey stat: A quarter of Brazilians say that they are proud of their people, describing them as welcoming and accepting, and highlighting the country’s positive social climate.

“I’m very proud of being Brazilian, maybe too much. But in a world as divisive as we’re living today, I think people are waking up to the importance of Brazil in society, because of our welcoming nature. Another word that comes to my mind when I think of Brazil is flexibility: whatever your religion or your sexuality, we live together. I’m definitely not saying that it’s a perfect country but the world needs more of that flexibility.”

Angelica Jopson, South Africa

Key survey stat: South Africans cite their country’s services (24 per cent) more than most nations, as well as housing, “social grants”, police and pensions.

“I have a strong sense of pride in the diversity of the country. A rainbow nation, as we call it, however imperfectly, has held its centre since the end of apartheid. We have 11 official languages, five of them in our national anthem and, for good measure, one of the world’s most colourful flags. Like a mad family, we might have internal divisions but we band together when it matters most.”

Listen to the full episode of ‘The Briefing’.

It’s that time of year (in the northern hemisphere at least) when high school graduates start weighing up where they might want to spend the next three to four years enrolled in programmes that could give them a shot on the career ladder, help them find a suitable life partner or usher them straight back home for a life reset.

Over the past few weeks I’ve been anywhere from the centre of crucial academic decisions (very useful having a university dropout in such conversations) to a casual eavesdropper as families discuss whether it should be Madrid or St Andrews. (“Really, I think we can get you set up much easier in Madrid with that nice El Corte Inglés around the corner and that massive new Zara Home.”) Is the US still an option? (“I’m not sure we want them looking at your anti-Trump posts while you were in student government dear. Better off with Eindhoven.”) And then there are the Asian friends who are concerned with security, overly liberal world views and gun-control issues in the US, Australia and Canada. (“I never thought we’d consider Bocconi in Milan or Nova in Lisbon but why not?”) At the same time, I’ve also heard that many recent graduates are struggling to find positions that might reasonably correspond with the amount forked out for their chosen degree. (“There’s no intake of new talent in any of the consulting firms that were on a recruitment drive six months ago.”) It’s at this point that my patchy academic creds and entrepreneurial streak kick in.

“I don’t think it’s a case of there not being any jobs,” I start. “There’s just not the soft landing your kids were hoping for. Why don’t they take some time off and see the world?”

“Oh, I don’t think we really want to be paying for a year or two of travel,” goes the sensible response. “Better they extend their studies.”

“No, no, no,” I counter. “I think they should see the world, fully paid and tax-free. I’m thinking they do a couple of tours with Etihad.”

This is when some parents start to shift in their seats, tense their bum cheeks and make a face. “Hmmmmm? I never really thought about that. A flight attendant?” At about the same time an enormous thought bubble comes into view to the left of their head.

“How will it sound when I tell our friends that Jonathan graduated top of his class in Pre-Mayan Urbanism and now works for a Gulf airline pouring gin and tonics?” The thought bubble grows larger. “I wonder how I can spin this in a positive way? That maybe he’s thinking of a career pivot to aviation law? I wonder what kind of discounts the family will get if he stays for more than three years?”

Degrees in early Persian town planning are useful at Monocle but having done a tour with an airline or a stint on a submarine is what takes potential candidates to the top of the CV pile. A few years walking the aisles of an A350 almost guarantees that a potential candidate knows how to handle most situations with a sense of calm and good humour. Moreover, they know how to mix that all-important G&T when a guest pays a visit to our HQs in Zürich or London.

“Is this really important?” I hear the concerned parent ask. Absolutely! These skills are more important than ever and make for a better breed of journalist, sales associate or budding publisher. As we also enter “my son/daughter is looking for an internship at Monocle” season, we’ll be looking for young talent who are just as happy to spend a few months on a La Marzocco as they are tapping away on a Mac.

Enjoying life in ‘The Faster Lane’? Click here to browse all of Tyler’s past columns.

When considering any new initiative attached to the name of US president Donald Trump, the first question to ask must always be: is this really what it purports to be? President Trump’s much-ballyhooed Board of Peace offers little indication that it is any exception.

The Board of Peace, officially established in January at the World Economic Forum in Davos, held its inaugural meeting last Thursday with a ceremony in Washington. Founding members gathered beneath signs flaunting the Board of Peace logo, which depicts golden laurels surrounding a globe that is oriented to present a western hemisphere almost completely consumed by North America. South America gets lopped off about halfway across Brazil, and Europe, Africa and Asia are all invisible.

Despite this slight, leaders from all of these continents turned up. The 27 countries that have formally joined the board so far attended the meeting, while 22 others were curious enough to send observers; also present was Fifa president Gianni Infantino.

Who is on the Board of Peace?

Trump has described the board, with characteristic understatement, as “the most consequential international body in history”. While the possibility exists that this might become the case, so far the board resembles a clubhouse of the authoritarians in whose company Trump has always seemed most comfortable. Actual signatories to the charter thus far include Azerbaijan, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, Morocco, Bahrain, and El Salvador. Those European democracies which have joined either have somewhat Trumpist tendencies (Hungary, Bulgaria) or are seeking the favour of the US for other reasons (Kosovo, which aspires to Nato membership, and to wider recognition of its existence). Members are invited to serve a three-year term, extendable to permanence upon paying the $1bn fee.

A few countries, and the European Union, attended the Board of Peace’s first meeting as observers, while a dozen or so others have formally declined Trump’s invitation to join. More are yet to respond, possibly hoping he’ll lose interest. There is also the special case of Canada, which was invited and had accepted, only for Trump to abruptly revoke the offer. (Possibly miffed by Canadian prime minister Mark Carney’s recent speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, during which Carney urged the world to think beyond and around the American hegemon.)

What will the Board of Peace do?

Beyond meeting every so often to nod along at Trump’s estimations of his own marvellousness, the first item on its agenda is allegedly Gaza, which Trump has frequently fantasised about rebuilding as some Mediterranean analogue of Atlantic City. The board’s framework includes an 11-person Gaza Executive Board, which includes Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, Trump’s all-purpose envoy Steve Witkoff, former UK prime minister Tony Blair, Egypt’s senior-most spook Major General Hassan Rashad, Israeli-Cypriot property tycoon Yakir Gabay and not one Palestinian (a proposed new Gaza administration, consisting of amenable Palestinian technocrats, is administered by the Board of Peace).

Nine members have pledged $7bn towards the board’s Gaza project, though it remains to be seen whether this money gets spent. Five board members – Albania, Kosovo, Kazakhstan, Morocco and Indonesia – have offered troops for a putative International Stabilization Force for Gaza, to be commanded by US Army Major General Jasper Jeffers. Though said countries might have done so betting that fellow board member Israel is unlikely to wave in a multinational contingent of militaries from largely Muslim countries.

The Board of Peace does enjoy the legitimacy conferred by UN Security Council Resolution 2803, passed last November, which formally welcomed Trump’s initiative as “a transitional administration with international legal personality that will set the framework, and co-ordinate funding for, the redevelopment of Gaza”. It is hard to imagine that the UN was sorry to hand over a task likely to be expensive, difficult and thankless if possible at all – or that Donald Trump will take any responsibility if (or perhaps when) the effort fails.

Andrew Mueller is a contributing editor and the host of ‘The Foreign Desk’ on Monocle Radio.

For most of the world, the Milano Cortina Winter Olympics began on 6 February. But the official Olympic torches began their duties more than two months before the opening ceremonies. The torch relay is a tradition that signals the lead-up to any Olympic Games and the latest round began on 26 November 2025 in Greece’s ancient Olympia before hopping over the Ionian Sea for a 60-stop tour of Italy.

Unveiled last April, the torches were designed by Carlo Ratti Associati and the Cavagna Group. Carlo Ratti, a founding partner of the studio and director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab, said the design process for the torches was a collective affair, with many people working on the mechanics of the burners. An Olympics torch must be as durable as it is beautiful and one for the Winter Games must also be braced for inclement weather and altitude. Dubbed “Essential” for their streamlined appearance that emphasises the flame, the torches – one blue for the Olympics and the other gold for the Paralympics – are made from recycled aluminium and brass alloy that reflects light.

Ratti joined Monocle in Milan to discuss the design process for the torches. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How did you get the job of Olympic torch designer?

There was a contest. [The committee looked] at things [we] had designed and one of the things [they also looked at] was [how you perceive] the value of the torch because it’s going to be seen by billions of people.

Where did you start the design process?

The beginning was like a relay in its own right. We all went to the Olympic Museum [in Lausanne], where the previous torches are. The other thing that is similar to the Games is that [the design process is based on] teamwork. [We worked] with Versalis, Cavagna, engineers, along with other people looking at the flame and the aerodynamics. It was not just one person with a blank sheet of paper.

How is this torch different from its predecessors?

If you look at recent Olympic torches, the exercise has been a lot like car design. At the core you have the burner where the flame is produced, with a lot of technical components, and the outside is built around it. What we tried to do was the opposite: we designed the torch around the burner and left an open slot where you can see the burner generating the flame. That also helped us to use less aluminium.

You mention car design: is it a reach to see classic Italian supercar heritage in [the torch]?

I think there is a little bit of that – Italian design of the 20th century but also a lot of technology. Working with Versalis, we did research on materials and performed many tests, minimising the design and making it the lightest torch ever. That was more difficult than just creating a shape around the core.

Does designing the torch earn you a pass that gets you into any event you like?

No, I don’t have those passes but I’ve loved every minute of it.

More design coverage from the Milano Cortina Olympic Games, read on below.

– From the Olympic Village to student housing: Manfredi Catella on building Milan’s future

The radio team meets every morning to plot out the day’s news shows, discuss what topics should be covered and which wise guests to book. On Thursday, as they were all huddled together, one of the production team apparently exclaimed, “Andrew’s been arrested!” My informant tells me that the room immediately divided into three camps: those who correctly deduced that the former Duke had been taken into custody; those who thought that Andrew Mueller, our esteemed host of The Foreign Desk had been chucked into the back of a carabinieri van (he’s in Milan as part of our Winter Olympics team – as in radio team, not pirouetting on the ice in a Monocle “M” emblazoned leotard); or, unbelievably, that yours truly had had his collar felt by the local constabulary. Perhaps it was the latter third who were responsible for what sounded like a little cheer emanating from the meeting room just past 10.00. When relaying these events to me, my informant, our senior news editor Chris Cermak, made it very clear that at no point did he believe that I had been hauled away. I think I believe him.

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor has always denied any wrongdoing regarding Jeffrey Epstein or in the way that he carried out his duties as a trade envoy, yet his fall from grace – having to renounce his titles, move to the rear end of windy Norfolk – has been dramatic. And his troubles have done little to embellish the desirability of the name “Andrew”. Its popularity peaked long ago but it is now on the endangered list in Britain. The latest turn of events will likely send “Andrew” the way of the dodo. Perhaps it’s time for all of the Andrews who remain to consider a modest rebrand. Could I pull off “Drew Tuck”? Perhaps our gruff-voiced Andrew Mueller could just be known as the “The Mueller Meister”. I’ll have a word with him.

One of the reasons that I’ve been having Cermakian chats this week is that he’s kindly booked me as a guest on The Briefing a couple of times. One of these was on Wednesday, when I headed into the studio to talk with Chris about a report from the Pew Research Center looking at what makes people feel proud of their country, based on a survey of 33,486 people in 25 countries (ie, it’s legit).

One of the reasons Chris, an Austro-American, had requested my presence was to quiz me on the UK’s woeful results, where 29 per cent of respondents said that they were not proud of their country, while 25 per cent said that they were. Nigeria came in second place on the negativity index, while in Indonesia just 2 per cent of people had a downer on national pride. And in the individual categories it wasn’t much better. Some 38 per cent of Italians were proud of their arts and culture, in contrast to 8 per cent of Brits (what about Mr Bean?). When it came to history, 37 per cent of Greeks were proud, 12 per cent of Britons and a meagre 3 per cent of Americans.

The truth is that the UK would never score highly in such a survey but if you asked Scots about Scotland and the Welsh about Wales, I am sure that the numbers would be more robust. Plus, our politicians have muddied the waters. The right believes that you have lost your marbles if you like the country (to be referred to at all times as “Broken Britain”) today, while the left always gets queasy near a Union Jack, fearing that you are about to bring back the empire. National pride is not a badge that the British wear well. We like being miserable contrarians.

But it will be interesting to see whether the royal family’s latest bout of difficult news headlines further damages how proud people feel of being British. Will the tarnishing of a supposed soft-power asset dim the nation’s mood? Maybe. But perhaps a forced reboot of the monarchy and what it represents, as well as a demonstration that in Britain nobody is above the law, will do us the power of good and make us look at our institutions and the rule of law with something close to pride.

To read more columns by Andrew Tuck, click here.

Stephen Miller, whose official title is deputy chief of staff for policy and homeland security advisor, is known in Washington as “Trump’s brain”, such is his reputation for masterminding many of the president’s most radical policies. But perhaps a more accurate moniker would be “Trump’s translator”. Miller doesn’t think for the president but acts as a conduit for his most extreme messaging and impulses. While Donald Trump frequently obfuscates, leaving people unsure if he really means what he says, Miller distils his bluster and spells it out in no uncertain terms.

Take, for example, when Trump sent the military into Venezuela to capture President Nicolás Maduro in early January. It was a brazen raid against another head of state and the world wondered if it marked a seismic shift in US foreign policy. Where Trump was vague, Miller was crystal clear: “We live in a world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” Miller told CNN. “These are the iron laws of the world. We’re a superpower. And under President Trump, we are going to conduct ourselves as a superpower.”

The full extent of Miller’s power is on display as the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) patrol agents rampage around Democrat-run cities, tear gassing and dragging residents out of cars. It’s the realisation of his life-long ambition and the manifestation of a world view that divides everyone into “us” and “them”. Within hours of Ice agents shooting and killing Alex Pretti on 24 January, Miller was on social media calling Pretti a “would-be assassin” and directing homeland security secretary Kristi Noem – who, in theory, outranks him – to claim Pretti wanted to “massacre” law enforcement.

Once again, it was Miller who was in charge of the narrative. Even when it backfired and Trump distanced himself from the “assassin” comment, there was no suggestion that Miller would step down. He is among an exclusive group of people that the president trusts absolutely – a trust built up during Trump’s first term when Miller was a speechwriter and senior policy adviser. At the time, the policies that he devised – including the Muslim travel ban and the separation of children from their parents at the US-Mexico border – were considered too extreme and many were reversed.

Now with the president emboldened by his second election win, Miller has found his moment. He is the architect of the mass deportations of migrants and the deployment of the National Guard and federal agents onto the streets of American cities including Los Angeles, Chicago and Minneapolis. In May 2025, when the normal rules of immigration law enforcement were not producing the results that he desired, Miller demanded that Ice hit an arrest quota of a minimum of 3,000 a day, paving the way for the brutish tactics and dragnet approach seen today. Miller’s public comments often skirt close to white-nationalist rhetoric, with The New York Times reporting that Trump once said Miller would be content if there were “only 100 million people in this country and they would all look like Mr Miller”.

The 40-year-old’s disdain for people from diverse backgrounds dates to his high-school years in Santa Monica, where he wrote a screed to a local paper denigrating Spanish speakers and Native Americans. (It’s also worth noting that Miller himself has a family history of immigration: he is the son of Jewish parents whose ancestors migrated from Russia in the early 20th century.) He moved in fringe right-wing circles while studying political science at Duke University before heading to Washington and working for a series of conservative legislators. It was his single-minded obsession with curbing immigration that caught Trump’s attention, but today, Miller’s reach in policy goes well beyond border control.

From flooding the zone with executive orders to greenlighting military strikes on Yemen and engineering Maduro’s capture, all of the Trump administration’s most audacious policies are marked with Miller’s stamp. So, for anyone wanting to know what Trump is really thinking – and what he might do next – they would do well to pay close attention to Stephen Miller.

Hungarian opposition leader Péter Magyar, who is leading in the polls ahead of the country’s pivotal April elections, is hardly the first politician to be threatened with the publication of compromising material of an intimate nature. Though if the best that his opponents can do is threaten to release video of a healthy 44-year-old man having consensual sex with an apparently enthusiastic partner, he is entitled to feel confident about the looming vote.

The honeytrap is, nevertheless, a venerable espionage technique, used throughout history to great effect – frequently on balding, pudgy, middle-aged male officeholders who have clearly not paused to wonder why 22-year-old lingerie model Svetlana finds their views on missile procurement so riveting. This past Valentine’s Day, the US Army Counterintelligence Command posted an image of a scarlet-clad woman making eyes at a gawky, bespectacled grunt with the caption, “It doesn’t take a mathematician to figure out 10 + 5 = honeytrap. Report suspicious behaviour.”

A model for such operations might be that which undid Sir Geoffrey Harrison, a UK ambassador to the USSR in the mid-1960s. Harrison embarked on an affair with a Russian chambermaid in the embassy’s employ, heedless of the near-certainty that she was a KGB plant. The Briton gave himself up to his superiors at the Foreign Office after the Red Army marched into Czechoslovakia in 1968 and was swiftly, if discreetly, recalled. Speaking about the incident years later, he said, “It is happening all the time to diplomats and journalists.”

The honeytrap is not exclusively a tactic of the West’s antagonists or a relic of the Cold War. Mordechai Vanunu was an Israeli nuclear technician who, in 1986, spilled details of his country’s officially denied nuclear weapons programme to a British newspaper. While in London, he struck up a relationship with an American tourist, who suggested a city break to Rome. The American tourist was a Mossad agent, as were her colleagues waiting in the Italian capital. They spirited Vanunu to an Israeli navy ship and back home to stand trial for treason and espionage. He served 18 years in prison.

Last year, a 60-something retired US Army Lieutenant Colonel David Slater, working as a civilian contractor on Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska – overseer of American nuclear forces – was handed nearly six years in the federal clink for conspiring to disclose classified material. In 2022 he had been chatting online, or so he believed, to a Ukrainian woman with what should have seemed a perturbing line in conversation: “Beloved Dave, do Nato and Biden have a secret plan to help us? American intelligence says that already 100 per cent of Russian troops are located on the territory of Ukraine. Do you think this information can be trusted?”

As long as there are ruthless intelligence services and lonely, gullible people in high office, honeytrapping will continue, which prompts the question of how to combat it. The most obvious way is, of course, to maintain an unforgivingly rigorous assessment of your own attractiveness relative to that of the vision gazing adoringly over the martini glasses as you expound upon the footnotes of this treaty that you’re negotiating. The other – amoral but effective – is to regard such importuning as a perk of the job.

Regrettably unprovable but persistent Cold War legend has it that during one visit to the USSR by Indonesian dictator Sukarno circa the 1950s and 1960s, special measures were taken to ensure his loyalty to the Kremlin. A bevy of comely KGB operatives were disguised as Aeroflot hostesses and deployed to the bar of Sukarno’s Moscow hotel under instruction to inveigle him to a room rigged with surveillance equipment and show him a good time. However, the Soviet spooks misjudged their mark: when they showed the subsequent good time back to Sukarno on film, he did not, as they might have hoped, cower in obeisance. Instead, he exclaimed his delight and asked for copies of the tapes.

Andrew Mueller is a contributing editor and the host of ‘The Foreign Desk’ on Monocle Radio. Listen to more about Hungary’s elections on Monocle Radio’s ‘The Globalist’ here.

The AlUla Arts Festival wrapped up this week. It’s an event that’s transforming perceptions and setting the ambitious tone for art and design in its namesake town in northwest Saudi Arabia. After touching down in its desert landscape earlier this month I was whisked from the airport through dramatic stone escarpments that emerged from seemingly endless expanses of sand, occasional oases of palm trees and horizons defined by low-slung mountains.

The region is clearly undergoing rapid development; diggers and excavators are a constant against the stunning natural backdrop. But those driving the project, the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), are establishing frameworks to ensure that change is as sensitive as it is swift. Case in point is a petrol station constructed from rammed earth by Jeddah-based SAL Architects, which rises from the desert on the town’s southern outskirts. It blends into the landscape and speaks to AlUla’s history as a cultural crossroad on the route to Medina. Even today, it remains a place for travellers to refuel.

It’s scene-setting architecture that responds to place. This ambition is also being harnessed by the AlUla Arts Festival whose programme included artist residencies, design prizes and exhibitions. Its aim is to help lay the groundwork for the region’s development in a way that’s appreciative of its past but striving toward the future. Here are five takeaways from the event, with applications that stretch far beyond the seemingly infinite Saudi desert.

Don’t be a copycat

“It’s not about mimicking the past,” says Sara Ghani, an urban planning and design manager at RCU, while explaining that it can be tempting to simply mirror the forms of AlUla’s ancient buildings, some 900 years old. Her team encourages architects of new projects to find ways of referencing place without replicating it. Take the Alula Design Centre. “The skin of the building is corten steel, not mud, but it references the city’s ancient breeze blocks – a contemporary building that reflects older character.”

Put on rose-tinted glasses

“There’s more than 7,000 years worth of continuous civilisation that have lived on this land and so we see AlUla as a place to learn from the past,” says Hamad Alhomiedan, arts and creative industries director at the Royal Commission for AlUla. Hegra, he says, is a case in point. A major archaeological site near AlUla, it features water wells and cisterns that never relied on mechanical pumps or electricity, as well as decorated tombs and inscriptions. It’s a 2,000-year-old benchmark for building better with less. “In AlUla, we see art and design excellence cascade from ancient civilisations to today.”

Build for the best

A good artist and design residency should have a legacy that extends beyond its duration. “They’re a living reference for designers working in a region,” says Arnaud Morand, the head of art and creative industries at the French Agency for AlUla Development, while moderating a panel on the AlUla Artist Residency. He articulates the importance of bringing in an international cohort of designers. “Through research, we can root future work in the land, the people and its history, so that design doesn’t land on top.”

Reframe regulation

A participant in the artist residency is Amsterdam and London-based Studio ThusThat. As part of the programme, they developed a new concrete-like material from slag (a waste-product of Saudi Arabia’s aluminium and copper refineries). And while it has the potential to play a part in a circular economy, a widespread introduction won’t be without difficulty. “Economies of scale and regulation framework are the big challenges,” says co-founder Paco Böckelmann. “But it’s about looking for opportunity: we found a factory where it was easier to mill the waste slag for us than store it.”

Look to art

Wadi AlFann, or “Valley of the Arts”, is a 65 sq m open-air, contemporary land-art destination. Set to open in coming years, it will feature works by the likes of New York-based Agnes Denys, whose ethos will be imbued in the development of buildings on the site. “We’ll be drawing inspiration from the artists that we’re going to commission,” says Iwona Blazwick, the lead curator for Wadi AlFann. “Land art is of and for the land, so we want an architecture that is made of and for the land, too.”

Nic Monisse is Monocle’s design editor. For more on AlUla and the movers and shakers that made waves at its arts festival, click here.